Recently, the British Education Secretary announced that students starting their A’ levels in England from fall 2015, will return to the previous system of an “all or nothing” exam at the end of two years of study.

Eventually, these changes will not only impact exams in England, but will also trickle into tweaks to the manner in which Cambridge International Examinations and EdExcel International exams are organised. It is still not clear whether Wales and Northern Ireland will adopt these changes; Scotland has a separate system.

The current system of units or modules has been criticised for allowing examination retakes and grade inflation. Policymakers hope that a return to the two-year exam cycle will help make A’ levels more rigorous and help prepare students for higher education. Universities have criticised the quality of GCSE and A levels in the UK, rather than preparing students for higher education or vocational training; A’ levels train students to succeed in exams.

This is a criticism that may sound familiar in Pakistan.

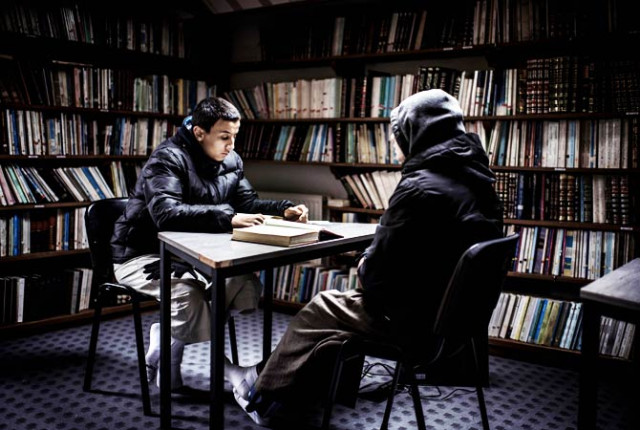

Over the past fifteen years, the mushroom growth of tutoring and a proliferation of schools and colleges that judge their reputation and success on exam results, a vicious cycle has been created where students seem to appear in exams perpetually during their O’ and A’ levels. A perverted mix of peer pressure, aggressive advertising and devaluing education to a series of grades, ensures that each year students are nudging more and more towards sitting exams in a wider array of subjects.

Whether it is in the UK or Pakistan, tinkering with syllabuses and changing exam timetables is a swift and neat way to “reform education”.

Politicians love such interventions as these are easily implementable and success can be declared once the changes are made. However, the outcome of these changes is someone else’s headache.

Over the past couple of years, a lot has been made of abolishing foreign qualifications and implementing a uniform curriculum across the country. Such rhetoric means well, but like the changes to A’ levels announced in England today, such measures don’t reform - they just tinker with the status quo. Across the globe, the best educational systems cater for a devolved curriculum and provide greater focus on pre-school and primary education.

An example would be that of Finland, where the system caters on fewer exams, recommends little or no homework, and recruits teachers from amongst the best candidates. In Pakistan sadly, debate on the curriculum revolves around how much importance the chapter on jihad should have, whether illustrations of boys and girls playing together is Islamic or not, or whether the chief minister’s message to students should appear at the front or the back of the textbook

Adopting the Finnish system of education or any other “model” is still a very far off goal. A massive number of school age children do not attend school and our first goal should be to ensure that no child is deprived of education. However, for education to be “fixed” we require a change of attitude towards what we mean by an “education”.

This will have to start amongst the affluent, partly because education providers for lower income groups aim to emulate their affluent peers. If the schools at the top consider exam success as the gold standard of a quality education, the same attitude trickles down, shaping the attitudes of both schools and parents.

While examination success is indeed important, the appropriateness of what we are taught and how we are taught is also important. Some imperfect albeit illustrative examples include students who complete O’ and A’ levels, but then struggle to appear in Central Superior Services (CSS) exams due to the perception that they favour the pedagogy of matriculation and Faculty of Science (FSc) students. Students hoping to attend state-run medical schools are encouraged to complete FSc rather than A’ levels as it is believed that it provides better preparation for competitive admission tests.

It is here where an examination focused approach towards education fails us. Education should aim to widen choice and facilitate flexibility.

Students should not have to bear the costs of short-sighted educational reform choices; their choices from five years ago should not impact their higher education pursuits in the present.

We must appreciate that education reforms take a long time to implement, and that changes to exams schedules or efforts to unify curricula (as favoured by politicians) will have limited impact. Instead, investing in teachers, focusing on basic and primary education, and recognising that the learning requirements of each and every child is unique, will truly usher in a much needed reform.

Utopian idealism? Perhaps. But the first important step must be the recognition by policymakers, education providers and parents, that such concerns are worthy of consideration.

Read more by Nadir here or follow him on Twitter @needroos

Education is not just about how many As you score

Here, debate on the curriculum focuses on whether illustrations of boys and girls playing together is Islamic or not.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ