Present Re-Inventions: A timeless amalgamation

Three Pakistani artists engage London audiences by reinventing historical, classical and religious images

Irfan Hasan Isabella Brant with Surveillance Camera (After Peter Paul Rubens), 2014, Irfan Hasan Madame Paul Sigisbert Moitessier with Phoropter (After Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres), 2014. PHOTO COURTESY: GROSVENOR GALLERY

Classical Figures

Miniature artist Irfan Hasan’s work has been stimulated by realism and his love for the human form for the past 10 years. Miniature paintings require patient rendering in opaque watercolour with a squirrel-tail brush, and this skilfulness is most evident in his largest portraits of 3.5ft x 5ft. With a flat white background typical of his style, Hasan’s Dante and Virgil in Hell 1: After William Adolph Bougeureau is inspired by Bougeureau’s depiction of a scene from medieval poet Dante Alghieri’s epic Divine Comedy. Eliminating the strange background creatures and chiaroscuro of the original, Hasan minimalises the painting to make it his own, focusing on the predatory posture of the subject. By leaving the victim in linear form, he makes the work look like a warped portrait of a deformed man. Hasan’s second large-scale work derived from the same painting interestingly depicts the victim. By flipping the image, he creates the illusion of the subject falling, with tension apparent in his muscles. Hasan’s smaller pieces also engage with the viewer, such as Isabella Brant with Surveillance Camera (inspired by Rubens) that questions the lack of privacy and intense scrutiny prevalent today. It makes one question the notions of alternating perspectives, conflict and appropriation of imagery.

Muhammad Zeeshan Jhulelal (series), 2014, Muhammad Zeeshan Maa (series), 2014. PHOTO COURTESY: GROSVENOR GALLERY

Divine juxtapositions

Muhammad Zeeshan, also a contemporary miniaturist, began as a cinema-board painter but now has permanent collections in some of the world’s major museums. Being the only artist to incorporate the technical laser-cut technology coupled with miniature painting techniques, he creates detailed and intricate depictions of a range of subjects, particularly popular imagery.

Irfan Hasan Self Portrait (After Anthony Van Dyck), 2014, Muhammad Zeeshan Zuljana (series), 2014. PHOTO COURTESY: GROSVENOR GALLERY

At first glance, one can observe the strong religious/cultural symbols present in Zeeshan’s work. Jhulelal, Maa, Zuljana and Sailani Baba all depict icons of worship and reverence from various religions (Hinduism, Islam and Sufism), who previously coexisted peacefully but are now embroiled in a physical and ideological conflict. Depicted against flat, bright backgrounds, Zeeshan’s subjects are painstakingly rendered, with certain areas painted in gouache. In his piece Zuljana, which depicts the religiously revered horse, Zeeshan pushes the boundaries of delicate miniature painting by using coarse industrial mediums such as graphite on sandpaper.

At the core, Zeeshan’s work not only reveals how religion has become an intrinsic part of our lives but also explains how the differences advocated by these bodies need not exist as religions are inherently more similar than different.

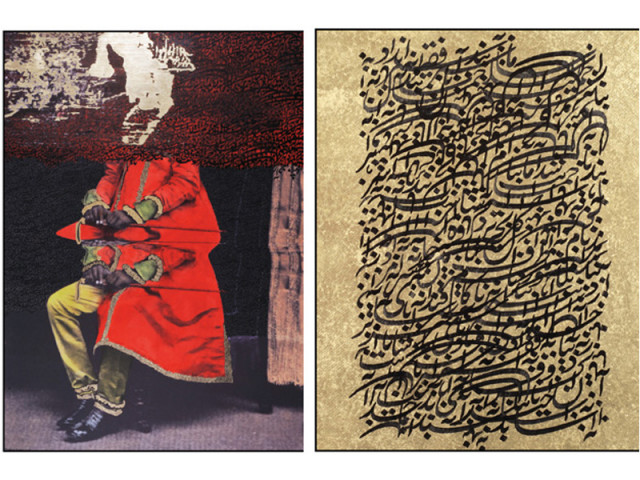

Irfan Hasan Cornelis Van Der Geest (After Anthony Van Dyck), 2014, Muzzumil Ruheel And How We Forgot Them 5, 2014. PHOTO COURTESY: GROSVENOR GALLERY

A call for awakening

Muzzumil Ruheel is a trained calligrapher who aims to create metaphorical interpretations by combining Arabic/Urdu text with form. His work is mainly about ‘historic revisionism’ or ‘reinterpretation of orthodox views’. In The accounts of hum, Ruheel overlays text on found images pasted on wasli paper. From afar, the text reminds one of an irregular pattern on cloth but a closer look reveals that the illusion is created by the composition and density of his text. In The Completeness of the Incomplete, Ruheel covers the found image entirely in text, so much so that what’s left of the original image looks like a ghost or a human soul. And within it lies a black hole that defines the subject’s hollowness, which in turn exudes an overall sense of horror.

Muzzumil Ruheel And How We Forgot Them 2, 2014, Muzzumil Ruheel And How We Forgot Them 1, 2014.

PHOTO COURTESY: GROSVENOR GALLERY

In his ‘And how we forgot them’ series, Ruheel places text in a neat and orderly form over old photographs of unknown people. His intervention works beautifully with the images and displays how an artist incorporates himself into the mysterious past of others. In the ‘The Land of dreams’ series, he does the same with old photographs of landscapes. By adding strange geometrical forms/spaces onto the images (again formed with text), Ruheel imposes his own imagery on lands that others had different dreams for, almost invading their space in the process.

While Ruheel’s text is precise and exudes perfection, it is consciously undecipherable and reflects the content of the images he has worked with. It is an attempt to make one aware of the jargon that is consciously altered and fed to audiences through the media or imparted in classrooms.

Shanzay Subzwari is a Fine Arts student. She tweets @ShanzaySubzwari

Published in The Express Tribune, Sunday Magazine, October 26th, 2014.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ