An inextricable history: How Persia influenced South Asia

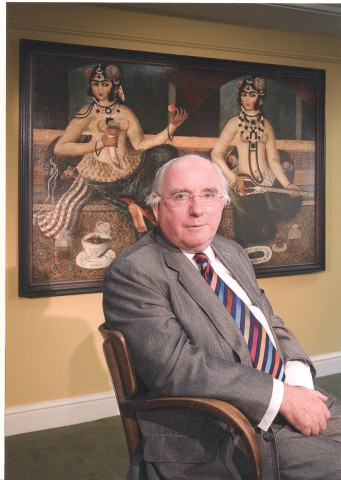

Francis Robinson takes a journey through time at IVS.

Historian Francis Robinson coursed through almost four centuries of South Asian history that witnessed the rise and fall of Persian influence on different aspects of South Asian life.

Robinson, currently at Royal Holloway, London, coursed through almost four centuries of South Asian history that witnessed the rise and fall of Persian influence on different aspects of South Asian life, particularly on its languages and religions.

“There has been a constant exchange between Iran and South Asia for thousands of years,” Robinson began. “South Asia gave the Sassanians [a pre-Islamic empire based in Iran] chess and Tantra, while Sassanians ruled over South Asia’s north-western parts.” With the advent of Islam, and frequent military incursions across South Asia’s western frontiers, cultural transactions were only to increase.

Explaining the spread of Persian, Robinson mentioned Firdousi. The author of the Shahnamah was a poet of Mahmud of Ghaznavi’s court, who brought Persian literary influence throughout the plains of the Punjab. After rise of the Sultanate of Delhi, this literary influence spread further East, all the way through Bengal.

Robinson’s lecture focused specifically on the Mughal era - from Babar through the 19th century, which is when Robinson claimed Persian influence declined. Robinson implied that the Persian language in particular relied on state patronage to flourish. It was under Akbar that the official position of a ‘poet laureate’ was created. “Akbar,” Robinson said, “patronised a total of 168 Iranian poets.” Persian then became the official language at every level of Mughal administration, and remained so until the British dismantled and rebuilt India’s administrative bureaucracy in the 19th century.

Whether through artistic merit, or simply through marrying the right people, Iran extended its people and practices in a culturally fertile South Asia. Robinson told the story of Mirza Ghias Baig, a Persian immigrant who rose to become a vazir in Jahangir’s administration, and whose daughter, Nur Jehan, married Mughal emperor Jahangir. Persian influence, through architecture and blood, eventually manifested itself in one of the most iconic buildings in the world - the Taj Mahal.

Another powerful influence has been Iran’s religious influence. “Sufism - Islamic mysticism - is no less than a projection of Iranian cultural power in the subcontinent,” Robinson said. Through reforms and new scholarship, Iranian pedagogy made its way to the seminaries of North India. Along with the Sufi order of Chishti, Iran can also be accredited for the spread of Shia Islam in South Asia, particularly in the Oudh region of North India.

In 1768, Shia congregational prayers took place for the first time. By the end of the 19th century, 2,000 imambargahs were built in Lucknow alone.

The decline came, Robinson explained, under British rule. South Asian elites realised that knowledge of Persian didn’t have the utility it once did so they switched to English. Nationalist and religious politics didn’t leave anything untainted, including languages. First Urdu replaced Persian, and subsequently became known as the ‘Muslim’ language.

Inevitably, the questions the audience had related to Pakistan’s present predicaments rather than those of the past. Sheema Kirmani asked about how and where dance and music was lost from the Sufi orders, and another audience member asked about Wahabi influences now prevalent in Pakistan. Sometimes it takes historians, not politicians, to remind us where we come from.

Published in The Express Tribune, April 11th, 2014.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ