Skins are the cheap part of this story. These Panaflex sheets, or skins as advertisers call them, cost just 16 rupees per square foot. It is where they are placed, in the sky above Karachi, that is worth millions — when you turn that space into a billboard. And so, Karachi’s sky too sells by the square foot: 200sq ft is one of the smaller scraps. It can rent out at Rs10,000 a month. The largest billboard, 5,000sq ft, that stands at the corner of FTC, rakes in over Rs9m a year for the cantonment.

But that figure won’t raise eyebrows. We live in Karachi, after all — a megacity where life is upsize by default. This is why we tend not to notice just how many billboards have gone up as we drive down Shahrah-e-Faisal, the city’s prime real estate for advertisers.

Who is behind the breakneck commercialization of Karachi’s real estate in the air? The city government, cantonments, other land-owning agencies, the 300 advertisers who get permission for sites and put billboards up, the advertising agencies that rent these billboards and the companies that make the chocolate that goes on the billboards.

Ironically, though, for objects that so dominate our public space, the business behind it is extraordinarily opaque.

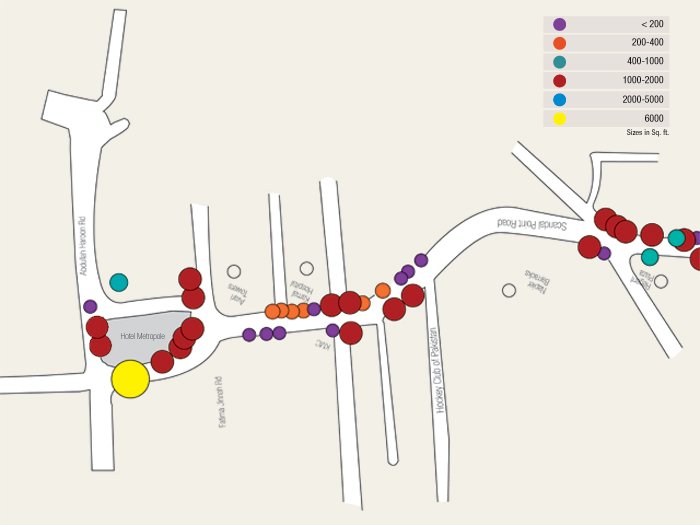

Each dot stands for a billboard. CREATIVE: KIRAN SHAHID/EXPRESS

The auction of billboards

It is called an 'upset' price or opening bid for a reason, but if you won’t be able to tell by the poker-straight faces on these men. About 30 of them, small- and big-time advertisers, turn up on February 10 for the first billboard auction of 2014 being held as usual by the city government’s local taxes department. Sixty sites are up for grabs and the cheapest billboards are opening at Rs333,500. By the end of the day the city government hopes to lock down Rs100 million in revenue from one-year contracts.

The auction begins once Noor Muhammad Baloch, the additional director for local taxes, takes the podium at the auditorium at Civic Center, the headquarters for the city government. Baloch is a lawyer by training and struggles with his English. He is instrumental to the success of the auction, however, as the last head of department, Akhtar Shaikh, was removed and the new director Rashid Khan is one month into the job. Baloch, who has worked here for about 20 years, knows the business inside out. His knowledge is matched by his girth; the man swims in his brown suit, its cuffs grazing his knuckles.

The counting begins in Urdu by the hundred thousand. “Bees laakh, ek hazaar." He starts off at Rs2,001,000 for a 60x20ft billboard at Boat Basin in Clifton. It was last in the hands of Aamir Siddiqui, who represents the advertisers as the general secretary of their 300-strong ‘union’, the Sindh Outdoor Advertisers Association or SOAA. He is in the audience in a sharp blue-and-turquoise striped shirt, open at the collar, giving him an air of confidence that comes from being well-liked, well-respected and well-moneyed.

Aamir’s contract on this billboard expired but he’s back to hang on to it for another year. Another advertiser, Owais Naqvi, the information secretary of SOAA, explains, "Sometimes it's a matter of prestige.”

A billboard running along Hotel Metropole. PHOTO: MAHIM MAHER/EXPRESS

Aamir immediately calls out, "Bees lakh pachees." (Rs2,025,000).

Owais enters the bidding with "20 55" for his OnAir company. The bids creep up by 25,000 rupees each time. Owais withdraws once the Brand Active representative butts in at the Rs2,450,000 mark. From there on it becomes clear that Brand Active is the clear rival. It is a swift climb from Rs2,550,000 as the bids dangerously tick up. Aamir and his rival are blank-faced but everyone else's eyes are glued to them. Even the man with the gavel, Noor Muhammad Baloch, is developing a twitch.

Rs4,200,000

Rs4,225,000

Rs4,250,000

Rs4,300,000

The heads move side to side as if it's a tennis match. The only thing that can give you away in this war is a nervously shaking foot. Sometimes there is an impossibly long pause between bids. The tension has ratcheted up in the room as if someone has turned the screws on the air itself.

Aamir quietly calls out Rs6.5 million.

Silence. Then enough of silence.

“Pensatth lakh, ONE!” cries Baloch. “Pensatth laakh TWO!” And then, as everyone holds their breath, “Pensatth LAKH THREE!" Ka-tAAk! Baloch’s wooden gavel cracks the podium. There is a feeble smattering of applause and the air expands around us. Aamir keeps his billboard for another year.

The city government takes three days to auction the sites and manages to hit the Rs63m mark amid lunches of greasy biryani, slow bidding and the odd eruption from an advertiser.

“They raise the rates and run off," exclaims one upset bidder when a virtually unknown Mohammad Advertisers counter-bids him up to Rs3 million on a Rs2 million billboard. Check if he's blacklisted, he urges Baloch, and is reassured that Mohammad Advertisers is a registered company.

An advertiser's worst nightmare is having a fake in the auction — someone who cranks up the prices but slinks off at the last minute, leaving you with a grossly inflated price tag. A faker will ruin you and sometimes they are planted. The old timers know how much advertising each billboard will reasonably attract in the year. And so, a Rs700,000 billboard shouldn't go for Rs4 million.

A fight breaks out over another Clifton 20x60ft billboard. “There are trees all over it,” moans one advertiser. Another one says, "First remove the trees and then we'll talk."

The director of local taxes is assaulted from all sides with the same complaint. "I've just been in office for a month," he protests from the stage. I can't answer for what happened before.

Aamir stands up. "You are insulting the process of the auction," he says with the authority of knowing the rules. "Your revenue will ultimately be hurt," he warns them before accusing the department of doing nothing to protect the advertisers from the freebie political banners that some parties put over their billboards without even asking, much less paying.

At the end of the day though, no matter how much they bicker, the city government and the advertisers are both doing business — a business that is growing day by day.

The origin of the billboard

The ancestor of the giant steel billboard was the humble and ugly bamboo stick. But the billboards affixed to bamboos rode low and close to the ground because of the limited strength of the sticks. It was only in 1987 that an advertiser named Shah Farid decided that innovation was in order. He claims to have introduced the steel ‘angle’ structure. These first went up near Karachi University and hardly cost Rs8,000 to erect. “Twenty-five years ago billboards were not considered a money-making business,” he says. “All over the world it was flourishing as far as a product’s logo was concerned.” But in Karachi there were hardly six advertisers and Shahrah-e-Faisal had 30 billboards at most. In those days the billboards just consisted of a girder with tin sheets, which is why advertisers like Aamir Siddiqui of SOAA were often disparagingly told they did “teen-dabay wallah karobar”.

Given that the advertising tax was just Rs5 per square foot and the ground rent was just Rs63 per sq ft it certainly wasn’t a profit-making business at the time. But men like Shah Farid, or at least those who had travelled, knew that outdoor advertising was an untapped goldmine in Karachi. By 1991, Farid says they experimented with tri-vision signs, which as their name suggests were motorised rotating ones that could display up to three brands. There was one at Shahrah-e-Faisal and one at Schön circle.

The tri-vision was particularly suited to the Lux soap campaign, as SOAA’s Aamir remembers from its triadic bevy of ‘Neeli, Babra and Reema’ whose faces would be timed to rotate with the traffic signal. Ideally three different brands could have been pitched for one tri-vision. “They were expensive,” he says, “but the [soap] brand manager didn’t want to share” when they suggested adding shoe-maker Bata. It didn’t make sense for them to have a face and a chappal alternating in one space.

But as a format, the tri-vision was just a fumble in the dark. The real explosion was just around the corner. It came in the shape of white Panaflex, first imported from Malaysia in 1996 (if Aamir’s memory serves correctly) at the unimaginable rate of Rs2,000 per sq ft. “People from Australia came to show us how to put up the first skins,” he says. Today that Panaflex skin costs just Rs16 per sq ft and largely comes from China.

After Panaflex skins the next advance came to printing technology in the shape of inkjets, by 2005. “Before that it would take four to five days to paint a billboard,” says Aamir, who now owns a VersaArt RE-640 eco-solvent large format inkjet printer by Roland and a Chinese XAAR dot printer. They can crank out a printed skin for a 200sq ft billboard in just 25 minutes and the machines fit in a flat’s drawing room. According to estimates, there are about 5,000 such machines in the country with room for up to 8,000.

Aamir Siddiqui sits next to his panaflex printer. He represents 300 advertisers as the general secretary of the Sindh Outdoor Advertisers Association and wants the same rules to be applied across Karachi. PHOTO: MAHIM MAHER/EXPRESS

The advertiser receives a CD of images from the ad agency and pops it in the computer attached to the printer. Once printed, the Panaflex strips are heat-sealed together and the skin can be draped over the billboard that very night. This material has changed the business to the extent that when Aamir asks one of his SOAA members how big his new billboard is on Hotel Metropole, the advertiser gauges size by the number of Panaflex strips he printed.

But most important is the structure that carries the skins. It comes from a ship — from Gadani. Great pipes from decommissioned oil-carrying vessels are extracted at the ship-breaking yard and are sent to Shershah’s scrap market. They come 20 feet long (12 inches thick) and cost about Rs85 per kg. The scrap is highly valued as the foreign metal is known for its strength which the advertisers rely on given that they need to take the weight of the billboard on top.

The pipe pieces take two days to transport from Shershah to Azeempura, which has the largest number of billboard-making workshops in the city because it is relatively under-populated. The pipe pieces are welded together to form 50ft tall main poles. Each joint takes three or four hours to electrically weld, explains Shahid Mukhtar who works at advertiser Nazeer Hussain’s workshop. The main pole is then topped by a t-shaped pipe which is four inches in diameter and forms the rectangular skeleton for the billboard. A frame made of partal or silver fir wood from Haji camp is screwed on top of the t-frame and the skin is stretched over it.

The pieces of pipe take hours to electrically weld to form a 50ft main pole for a billboard here in a workshop in Azeempura. PHOTO: MAHIM MAHER/EXPRESS

The process of making a billboard takes 20 days and the workshops have about five orders each per month on average. A small 10x20ft billboard will cost about Rs70,000 to make. At night the parts of the billboard are transported to the spot. They dig into the ground and drive in eight one-inch bar shafts, five feet down. A 2x2ft base plate is set on top and the main pole is screwed in. A crane is used to hoist the entire structure up.

A municipal authority’s engineers are supposed to check for safety standards. The tricky part is digging deep enough to make sure the main shaft will be stable. “Most of the land in DHA is reclaimed and so it is not good enough to put the pole just three to four feet in; it has to go down 8ft,” warns Shah Farid. The pole is being erected on what is essentially sandy land and sand keeps shifting under the surface of the earth. “You need to use at least three different kinds of cement so that when the sand moves it can take the load,” he explains.

Gone are the days of honest engineers, though. SOAA’s Aamir used to have a Parsi engineer known for his honesty to vet his billboards. The man would refuse to issue a completion certificate if even one rule was broken. “Now we get the certificate first and then put the billboard up,” Aamir says with a sheepish grin. No one gets the third-party insurance anymore either.

And so there is a complete absence of regulatory oversight for these billboards which can weigh about 250kg. This is why, when they fall, they can kill you.

Damage control

The nine deaths reported from falling billboards in 2007 became a turning point in the way the city saw advertising and how it should be regulated.

There was an unsuccessful attempt seven years earlier by city administrator Brig. (retired) Abdul Haq to get all the stakeholders under one authority so that permission to put up a billboard should come from one place. The system then and indeed now defies logic: you have to apply to the authority in whose jurisdiction the land falls. It is sort of like having to get a driver’s license from DHA if you want to use its roads but another one from the city government if you want to use its roads.

It was only until 2003 that the first billboard laws were made. The Advertisement and Signage By-laws were passed by the City Council under city nazim Niamatullah Khan. But they weren’t enforced. It would take the unlikely duo of a young hot-blooded mayor and a dour bureaucrat to accomplish that.

When Mustafa Kamal became city nazim in 2005, he wanted to tackle the billboard ‘mafia’. But that would require the right officer to do the job: a man who didn’t want it. That was Rehan Khan, a statistician by training, who had excused himself from running the local taxes department just a year earlier. Any officer of less moral fibre would have never voluntarily given up such a lucrative post.

A year into his tenure Kamal asked Rehan to come back and run local taxes. Rehan put forward 13 conditions. He got nine. “I told him [Mustafa Kamal] he’d have to swallow a bitter pill and cut them all down,” says Rehan, “and just give permission to the legal ones.” In those days there were up to 5,000 billboards in the city government’s jurisdiction but less than 1,000 were legal. Little did Rehan and Kamal know at the time that the battle they were fighting then would stand them in good stead.

By mid-2006, they got the city down to what Rehan calls “ground zero” by taking down all the legal and illegal billboards and reimbursing the taxes of legitimate ones. “There was a lot of pressure but Mustafa Kamal told me, fix this stuff. Make the city beautiful,” Rehan recalls.

Advertisers were asked to give feedback on the new rules they were drawing up. By December 2006, the amendments to the 2003 by-laws were pushed through the city council. There was even talk through Governor House of making Shahrah-e-Faisal billboard-free. All this pain would be rewarded. When the pre-monsoon rains and winds hit Karachi on June 23, 2007, nine people were reported killed by billboards that keeled over. A total of 104 hoardings fell but Mustafa Kamal triumphantly proclaimed: “Only four billboards fell in our jurisdiction and no one got (as much as) a scratch.” (Actually, the number was nine). But Cantonment Board Faisal’s jurisdiction, essentially Shahrah-e-Faisal, was the worst hit, as over 50 fell there.

“Hum saray footpath pe aa gae,” recalls SOAA’s Aamir, referring to advertisers. Mustafa Kamal used the tragedy to come down hard on the entire business and even got the cantonments and corps HQ to the table. In a major breakthrough, they all agreed to follow the same rules, for structure and above all safety. “The cantonments and the Station Headquarters appreciated the change,” recalls Rehan Khan. “But they implemented it in some places and not in others.”

It took seven to eight months of negotiations with advertisers to come up with a solution.

According to Rehan Khan, an advertiser named Faiz Habib, who was also an engineer, designed a new structure. They would no longer use solid tin plating which added to the weight of the billboard. Instead they designed the lighter partal wood skeleton. An old skin would be stretch across it and the new skin would be slipped over that one. “This way, when the wind blows, the skins will rip but the billboard won’t come down,” says Aamir.

At the end of the day, though, with the exit of Rehan Khan and ultimately Mustafa Kamal, the system they devised fell apart. “In this case, the by-laws were implemented for just five years (2005-2011),” says Rehan. He resigned from local taxes in October 2011. Today he serves a "punishment posting" for his efficiency in the sports and recreation department.

Rehan Khan and Mustafa Kamal were certainly not the only vanguards in the fight against the creeping rash of billboards. There have been others.

Shahid Aziz Siddiqi, who was the commissioner of Karachi from 1986 to 1989, headed the city’s first Aesthetics Committee. (It was formed by then Governor Rahimuddin Khan). “We felt that hoardings were a major problem as they defaced the environment," he recalls. They felt that at least one road should be taken as a model example and they picked Shahrah-e-Faisal.

They served notices to the advertising companies, saying that under the rules they were hazardous. "I had most of them removed," says Siddiqi. “Three-fourths of them were cleaned up.” But the companies went to court in 1988 and he had to back off even though he had the support of men like Ardeshir Cowasjee, who was on the Karachi Development Authority board at the time. "But somehow I felt the pressure,” he regrets. “Within the cantonments and city government there was pressure because their revenue streams were being affected. It was an almost single-handed battle.”

Battlefield billboard

Noor Muhammad Baloch is the additional director of local taxes at the Karachi city government. He is constantly looking for ways to protect his turf from the cantonments. PHOTO: MAHIM MAHER/EXPRESS

An unnatural amount of warm yellow sunlight floods the office where much of the action unfolds on advertising and billboards. The city’s local taxes department is blessed with such luminescence only because it is located on the 10th floor. In the rest of the world, real estate grows more coveted by the floor, but at Civic Center it is quite the opposite. Being on the 10th floor is punishment — there are only two working lifts in the building and the mayor, who signs all the checks, is on the ground floor.

Bathed in this golden hue, is the additional director for local taxes, Noor Muhammad Baloch. Whenever you call him, he is busy working the files, giving briefings, carrying out orders or gathering material to fight the cantonments.

Of course, the city government is no match for the cantonments in Karachi and officials like Baloch have no illusions about their station in life. “Bandook ke saey me hum to kachra uthanay wallay hain,” he says. We are the garbage men who work in the shadow of the gun.

Baloch’s words are wrought but this much is true that Karachi’s billboards have become hotly contested commodities in a fight of unequal opponents. “The cantonments are so powerful, they can put a billboard here if they wanted to,” adds Karachi Administrator Rauf Farooqui, pointing to the spot between his feet in his office at Civic Center. “You can only go after them if Allah helps you.”

Herein lies Karachi’s biggest tragedy: the mayor doesn’t control the entire city and bodies like the cantonments operate independently. There is no better example of the chaos this wreaks than a nine-year skirmish between Cantonment Board Faisal and the city government. Evidence abounds in a blue file stuffed with letters dating to 2005 (but this is not necessarily the start of the problem). The sheaves of correspondence, stamped from top to bottom, carrying cryptic instructions and multiple signatures, demonstrate how the cantonment and city government went round and round in circles. But for the purposes of this space, if a graph were drawn, the conflict would show three peaks: in 2005, 2008 and 2010.

Uncharted territory

The fight over jurisdiction between Faisal cantonment and the city government starts, innocuously enough, with a map in 2005. Would the Faisal cantonment please provide one to the city government because billboards were showing up in what it considered city government turf: COD bridge, Karsaz, Millennium Mall and National Cricket stadium. When the city sent its staff to check who had allowed it, the men putting up the billboards told them it was the cantonment. But they didn’t have any proof. Would the cantonment be so kind as to confirm this? The city didn't want third parties taking advantage of free advertising.

This is where the niceties end.

When the city didn't get the kind of response it wanted from the cantonment it published an advertisement in the newspapers in 2008. It warned advertisers that only the city could give them permission to put up billboards on certain roads. An appalled Faisal cantonment retaliated with its own stinker, saying that the city’s "misleading" ad was likely to cause "legal and administrative embarrassment".

The problem is that no one map with clear boundaries is apparently used by all the land-owning agencies in Karachi (there are about 18). Their officials have a good idea of roughly where their jurisdiction ends but as the letters between the cantonment and city government show, there is no one digitalised document they can all rely on when there is a dispute at a boundary line.

This is why it started to get ugly in the middle of 2008. Faisal cantonment accused the city staff of ‘trespassing’ by removing billboards on signal-free corridors I and II, Rashid Minhas Road and Gulistan-e-Johar, which it considered its turf. "Please return the same immediately," came the order. "We again, therefore, request to instruct your staff not to interfere in CBF limits".

Like two petulant children, Faisal cantonment and the city government have ripped the skins off billboards in each other’s areas. They have taken down pole-mounted signs. They have threatened each other if new billboards are allotted or auctioned in disputed areas.

Road & footpath ownership

Here lies the tricky part: who owns the roads and footpaths where you can put up billboards?

A road is described as immovable property. And the city government, which follows the Sindh Local Government Ordinance, 2001, relies on a section on ownership: you own it if you inherit, were transferred or built a road. It gives the inheritance example via Shahrah-e-Faisal (from Palace Cinema to Star Gate), which was part of the National Highway in the 1970s, and thus belonged to the Government of Sindh. In the 1980s the government of Sindh transferred it to the city government.

The city also considers it an internationally accepted rule that if you own the road you also own the footpath and central median or island with it. The only problem is that in many cases these roads fall in the cantonments. So, for example, Shahrah-e-Faisal runs through or past at least two of them: Cantonment Board Karachi and Cantonment Board Faisal.

The cantonments argue two points. First, that they are the municipal authority and hence can do as they like with billboards in their territorial jurisdiction. And second, that roadsides, footpaths or berms are C-class land which always legally belongs to a cantonment. “So the cantonment has the authority to install all kinds of hoardings on the berm of the road,” says lawyer Ashraf Butt who represents the cantonments.

As Faisal cantonment and the city fought, each side found innovative ways to try to prove its case.

The city said that it had the right to put up billboards in cantonment areas because it had constructed the flyovers and roads there. While this was true for many roads, it didn’t apply to all of them. “Please desist from interfering in the municipal affairs of the Federal Government,” Faisal cantonment haughtily proclaimed in one letter from the file. “Though we do not intend to be entangled in this avoidable argument, … we have paid Rs56 million for widening of Habib Ibrahim Rehmatullah Road…” This nullifies the city’s argument that it entirely pays for the road upkeep.

Faisal cantonment drove the screws in a little deeper when it also wrote, on May 12, 2008: "We sincerely appreciate the construction of roads and bridges out of the Karachi Package financed by the Federal Government”. The city couldn't always claim that it had paid for some roads because it received the money from the federal government — and the cantonments are part of the federal government.

And so Faisal cantonment accuses the city of “muddl[ing]” municipal jurisdiction with road ownership. It feels that construction works “do not erode the municipal supremacy of Cantonment Board in its notified jurisdiction by any instance".

Shahid Aziz Siddiqi in his study in Karachi. When he was commissioner of Karachi from 1986 to 1989 he headed a committee that tried to tackle billboards. PHOTO: MAHIM MAHER/EXPRESS

And thus it seems as if the cantonments do have a point, at least when it comes to the city's argument that only it pays for the roads. But there is a higher principle which can be applied. Former commissioner Shahid Aziz Siddiqi, who was also once director of excise and taxation in 1974, gives the fascinating example of the dispute over taxing Capri Cinema, which was located in a cantonment area. This was a time when Karachi was a city of cabarets and saloons and the entertainment tax really mattered because people from the Gulf flocked here to party.

The government of Sindh filed a case before the ministry of interprovincial coordination. “There can’t be a federal island in a provincial jurisdiction,” it had ruled, according to Siddiqi.

But new disputes keep coming to light. By 2013, when Faisal cantonment advertised an auction for new billboards, the city reacted badly because some of them were in what it felt was its jurisdiction. In a last-ditch attempt to solve the festering problem, the city turned to the Survey of Pakistan, asking for maps showing boundaries it shared with cantonments. But the Survey of Pakistan said it didn’t have them.

Even if a map clearly marked out the jurisdictions, the cantonments and the city follow completely different laws. The city government follows the Sindh Local Government Ordinance, 2001 (and 1979, 2013 etc) and Faisal cantonment, The Cantonment Act, 1924. So the cantonment would repeatedly say that the laws of local government didn’t apply to it. Or as it argued in 2010, when a fight broke out over the removal of displays at Karsaz flyover, The Cantonment Act had an “overriding effect” on all other laws of the provincial government and city.

(Download: Military Lands and Cantt Hoarding Policy 2012)

Banking on billboards

Without maps, it is hard to say exactly how many billboards there are in Karachi because each land-owning agency puts up its own and they do not coordinate with each other. For their part, advertisers have blithely put the number at 3,000 billboards.

Consider this: From Hotel Metropole to Gora Qabristan there are a total of 141 billboards on both sides of Shahrah-e-Faisal. This is mostly the jurisdiction of Cantonment Board Karachi and the Station Headquarters. Clifton Cantonment Board (not including DHA VIII) has 1,129 billboards.

On Shahrah-e-Faisal there are so many billboards that they are positioned one on top of the other, breaking the 200ft distance rule. “There is no [space] left in Karachi," says Aamir Siddiqui of SOAA. “The logical and ethical [sites] have been taken.”

But ethics are the last thing on everyone’s minds given the cash involved. The first indication is that no one is following the city government rules on size. The standard sizes are: 10x20ft, 15x45ft, 60x20ft. But advertisers, the cantonments and city government have been extremely creative. Someone had the brilliant idea of inventing the 125x40ft billboard, which you will find at the corner of FTC by the flyover as you turn left to Kala Pull. It is currently advertising a chocolate bar.

CREATIVE: SAMRA AAMIR/EXPRESS

The pylons on the central island from Punjab Chowrangi to Boat Basin are illegal. So are the small 4x6ft ones opposite Regent Plaza outside the army recruitment centre. Another new trend is to stand a 60x20ft billboard upright, as you can see in front of the Station Headquarters. The worst offenders are, however, the illuminated ones that have taken over roundabouts, as you can see outside Dolmen Mall, by Three Swords and from time to time temporary signs in front of Bagh Ibn-e-Qasim.

There are no rules and the cash is rolling in. Clifton Cantonment Board made Rs147 million from outdoor advertising in fiscal year 2012-2013. The city government made Rs825 million. It works by allotment and auction. An advertiser goes to the city government or cantonment and tells them they want a particular spot to put up their billboard. The city grants permission, the advertiser pays the combination of land rent and the sky tax, which as its name suggests, is the tax you pay for the part of the billboard in the air. So, for example, from Hotel Metropole to Gora Qabristan the tax for a 60x20ft billboard is Rs3.5 million per year.

This chart shows how much the Karachi city government (KMC/CDGK) has earned from billboards over the years. The Clifton cantonment earned Rs147 million from outdoor advertising in fiscal year 2012-2013 in comparison.

The problem with allotment is that it is entirely at the discretion of the municipal authority. One of the more dangerous trends is allowing a big company to do its CSR on a greenbelt. They cut a deal in which the company agrees to maintain the grass and landscaping on the greenbelt – but it is allowed to put up advertising or billboards to make up the costs. Karachi Cantonment Board has done this with an advertiser all along the wall of Gora Qabristan where there are seven 8x30ft panels. This is called a “beautification package” which is a win-win for the cantonment as it absolves it of its municipal responsibility and the advertiser makes a profit by putting up tax-free free billboards. This is why auctions are considered a more open and transparent method, despite the back-deals.

Billboards didn't used to be such a big business and the cantonments certainly didn't understand this. Rates used to stay the same for years. Strangely, though two major shifts in the political landscape had a surprising effect.

The first one came in the shape of a military dictator. Shah Farid, who has been in the business for about 25 years, tasted this first hand. He says he had roughly 80% of the billboards in DHA on five-year contracts and used to pay Rs5 per square foot in the ad tax and Rs63 in ground rent. But then, in 1999, they decided they wanted to take the ground rent from Rs63 to Rs1,500.

The second political shift came in the shape of the lawyers movement. And here again, the business of billboards was affected. One cantonment board tried to increase its rates in 2008. But the advertisers took it to court and won the case.

The court ruled in 2009 that the cantonment couldn't increase its rates unless it was sanctioned by the federal government and published in the gazette. All of this is laid down in the laws the cantonments are supposed to follow (Section 60 of the Cantonment Act, 1924).

Before the lawyers movement the advertisers didn't necessarily have faith in the judicial system. “The tehreek gave us relief,” says Aamir of SOAA. Otherwise they never felt anyone would take on the powerful cantonments or give a judgment against the government.

Thus, in 2013 when the Cantonment Board Clifton decided it was going to change the way it wanted to do business, the Sindh Outdoor Advertisers Association felt emboldened enough to take it to court. (Incidentally, when KMC tried to increase its rates in 2011 even it couldn’t do it without first listing it in the official gazette. But as SOAA rejected the rates they couldn’t do anything.)

To explain the case in ridiculously simple terms, the Cantonment Board Clifton decided that it wanted to raise rates and possibly auction instead of allot sites for billboards. Out of Clifton’s 1,129 outdoor ad sites, 329 were chosen to be auctioned on September 23 and 24.

SOAA filed a petition in the Sindh High Court and was represented by Barrister Farrukh Zia Shaikh. SOAA argued that the cantonment had violated its own rule of acquiring permission from the federal government before making any changes in rates. The Cantonment Act of 1924 says that once the federal government approves a change, it needs to be published in the official gazette. SOAA’s lawyer Shaikh called these “cowboy tactics”.

Shaikh was relying on the previous judgment in a petition four advertisers filed against the Cantonment Board Karachi and won. “It was a fantastic order,” says Shaikh. The court ruled that the Karachi cantonment couldn’t raise its rates without the federal government’s sanction. (The cantonment has since gone into appeal in the Supreme Court).

At the heart of Clifton cantonment’s argument is a nifty bit of wordplay about its three streams of revenue: taxes, fees or charges. The rule is that if a cantonment wants to increase a tax it must go to Islamabad. The federal government has to approve it and it has to be put in the gazette. But if it is a fee or charge it doesn’t need to go through that process, explains DHA’s lawyer Ashraf Butt who is fighting the case against SOAA.

SOAA tried to stop Clifton cantonment from holding its auction but the cantonment won a stay order. The court said, however, that while the cantonment could hold the auction it couldn’t finalize the results. What transpired is sub judice and cannot be discussed in this space.

For whatever it is worth, Clifton cantonment CEO Adil Rafi Siddiqui argues that auctions are more transparent as everyone gets to take part. “If there was not this option [of an auction] then it would just be at my discretion of who I gave [a billboard] to and who I didn't,” he says. “I'd be very happy doing that.”

This case notwithstanding, Clifton cantonment hopes to forge ahead with a new system of auctions at some point in time because it feels it is more transparent. There will be no “nocha-nochi” or clawing at each other among advertisers once we do this, argues Clifton recovery officer Nadeem Akhtar. He and his men work the graveyard shift to keep an eye on advertisers when they put up billboards at night. That is also the best time to catch defaulters. Nadeem’s unusually violent language befits his look. He wears his sunglasses indoors. He is ex-Navy but there is less of the tar and more of the thug in his maila-ness. You can tell he is the kind who understands ‘nocha-nochi’ because he has it in him to do just that. Strip you like an animal from the scalp to your toes if you didn’t pay in time. “Yeh badmash control nahi hote aam admi se,” he says, describing his job. And you can tell that he has very special talents. The very term “outdoor vigilance” he uses carries the weight of being up against, vigilant, against an enemy. With disdain he explains the advertisers try to sneak in larger billboards than approved: “They try to stuff a 21x22 bed in a 14x14 room.”

Two billboards 60x20ft side by side at Submarine Chowk show how the rules can be bent. “They were colluding,” Nadeem says. Two advertisers thought they could go behind his back and join their separate 60x20ft billboards to make a 120x20ft. For weeks he ensured they were empty. But if you drive by now, you’ll see an ad on them. Someone took a kickback somewhere to let this happen.

SOAA’s Aamir is the first to acknowledge that this is a dirty business. But he wants to change it. The CEO of Signways Communication became involved in SOAA precisely for this reason. “I have no choice,” he says, referring to his fight for rules and regulations. Even the CEO of Clifton cantonment board gives Aamir grudging respect as does the city government and other advertisers, despite their differences.

At the end of the day the Hobbesian social contract motivates him: if we all follow the rules no one will get cheated. This is why he considers the city government a role model and the “lesser of two evils”. “At least they have their own rules.”

And so, Aamir took a stand when some advertisers cut down trees to put up billboards. “This will give us a bad name with the public in the long run,” he said. But when he brought it up at a SOAA meeting he was beaten and bloodied in a fistfight.

Shrinking space

These giant photographs tell us what to buy, eat, drink, use, crunch on, spit out, fry our samosas in. What galls is how many people in Karachi like billboards because they see them as symbols of a society’s progress. They say they make our world more colourful. They do not see the monopolization of the landscape and visual pollution. An expert once described them as: “The only medium you can’t turn off.”

The Karachi administrator or unelected mayor, the CEOs of our cantonments, the 300 advertisers, the hundreds of companies, all want to put up more billboards because they make them millions of rupees. But this is money that does not get funnelled back into our roads and streets in terms of better footpaths, tar, greenbelts.

We fail to notice the slow expansion of billboards because we don’t use the vertical space they take up in the air. You only realise it once it’s gone. Sometimes it comes in the shape of a tree stump.

Outdoor advertising is also part of a scary rise in “neoliberal” urban governance: maintain a greenbelt or roundabout for the city government in exchange for rights to sell the space to advertisers. Have you seen the big ice-cream cone on the green belt by Two Swords in Clifton?

They may not bother you today as you speed down Shahrah-e-Faisal. Perhaps you don’t need to use the footpath which has been taken over by the poles. The billboards that hang over into the road don’t bother you yet. Keep looking at the cooking oil, the soap, the pizza, the cell phones, the biscuits, the toffees, the banks, the chocolate, the lawn, the washing powder. This city’s roads have turned into a supermarket aisle for Gulliver – and you, the Karachi resident, are a Lilliputian.

Downloadable maps:

S.I.T.E Town

Orangi Town

North Nazimabad Town

New Karachi Town

Malir Town

Keamari Town

Landhi Korangi Town

Liaquatabad Town

Lyari Town

Jamshed Town

Gulberg Town

Bin Qasim Town

Baldia Town

COMMENTS (10)

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ

1714024018-0/ModiLara-(1)1714024018-0-270x192.webp)

Good work but couldnt go through the whole article. You should make a documentary to really make sense out of it.

i live in the west and whenever i visit Karachi, it drives me crazy, not to mention the number of people in one city and that is still a city (not a province) plus the crazy billboarding with billboards size of tallest buildings in canada

Just to clarify, the complete OOH (Out of Home) portfolio for Karachi stands at a little over 8,000 assets. These would include all the creatives being done, the hoardings, the BQS, the pylons, the pole signs and any other form of large scale advertising that grabs the consumer while he is on the go (not banners, etc - those are tempoary).

Is this the first time ET has actually published an article backed up by data? And informative infographics? Good job!

Great research. These billboards are a visual nuisance. In my opinion every billboard in Karachi should be replaced by a tree. But billboards get you money which is obviously more important than what trees give you: you know, that useless gas known as oxygen.

Really good report.

Good job Express Tribune! Very insightful article.

Nice article covering the scenario quite completely. Regarding the menaces created by the Billboard industry, the menace is not created by the professional Billboard companies its the companies whom are handelled from power houses and after this any thin else is abserd to share.