Nato supply route and sanctions

Pakistan’s folly is that it has tied foreign policy to public passions.

Of course, sanctions are not yet on the cards but if imposed, they will be tough for Pakistan given the fact that its economy is in an oxygen tent and the oxygen comes mostly from the US and its allies. Universal sanctions are disastrous for any country, but they require all permanent members of the UNSC to agree to them. Partial sanctions initiated by a single country — in this case the US — are less dangerous but they can still put Pakistan under a lot of pressure. Take the example of Iran: the sanctions imposed on it are partial because China, India and Russia do not go along with them; nonetheless, Iran is under pressure because the allies of the US are willing to back them.

Pakistan, of course, will be backed by China and no universal sanctions will be imposed — at least not yet. But even unilateral sanctions imposed by the US will damage Pakistan more than they could Iran. Pakistan is dependent on direct assistance from the US and on aid from multinational institutions in shape of concessional loans. These can be foreclosed and repayments made stringent. Sanctions are bad for any country because they signal the extent to which the country has been isolated from the international community. Isolation again is a relative term: Iran can afford it because its economy is up to 90 per cent dependent on oil exports for its revenue, which the world must buy. Pakistan cannot afford isolation; its liabilities are so big that China cannot bankroll them even if it wanted to.

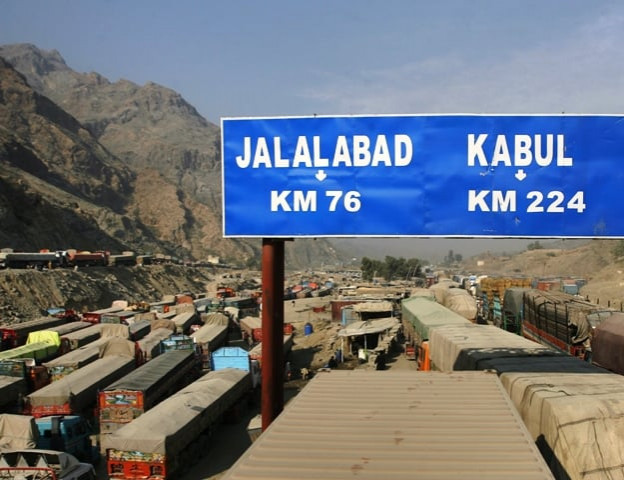

Mr Mukhtar was referring to the UNSC resolution 1386 (2001), which called upon “Member states to contribute personnel, equipment and other resources to the Force and authorised those states participating in it to take all necessary measures to fulfil its mandate”. Pakistan has been in defiance mode since November 2011 when the Salala incident took place, but the causes for umbrage were a bit older, which included the killing of Osama bin Laden in May 2011 and the even earlier incident of a CIA contractor killing two Pakistanis in Lahore. The government subsequently decided to throw its foreign policy to parliament, which had already passed impractical strictures on the US.

The parliamentary committee in charge of laying down principles for the conduct of Pakistan’s foreign policy promulgated the new regime of rules of engagement in March but after endorsing them, parliament splintered internally over its implementation. The rules were loaded with the kind of red tape measures that would make the execution of any agreement over the supply route almost impossible. Highly emotive in content that was reflective of concerns of the military, the new regime asked for a formal apology from the US over the Salala incident and a nuclear deal comparable to the one signed by the US with India.

The result is a stalemate. Writing in this newspaper, senior diplomat Tariq Fatemi stated that stalemate was not an option for Pakistan: “Not only did the process [in parliament] proceed at a desultory pace, the government did nothing to restrain those who sought to whip up popular passions in the guise of national honour and dignity. In the process, the government may have scored a few brownie points, but today finds itself in the straitjacket imposed by the parliamentary resolution”. Pakistan’s folly is that it has tied foreign policy to public passions and is now hamstrung to employ flexible diplomacy where needed.

Published in The Express Tribune, May 8th, 2012.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ