Interview with a spy: ‘Step into Pakistani shoes’

Former CIA station chief asks his fellow Americans to understand Pakistani threat perceptions, frustrations.

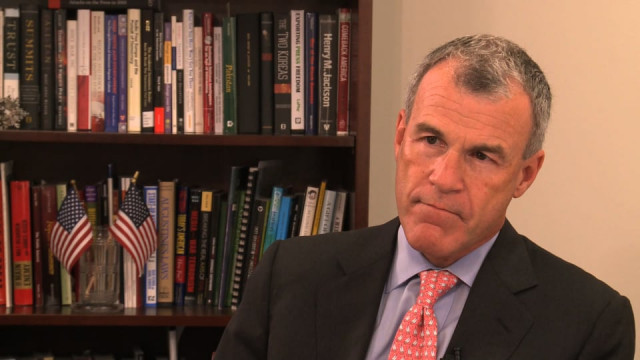

For a former spy, Robert Grenier speaks remarkably like a diplomat.

In an exclusive interview with The Express Tribune, the former top American spy in Islamabad said he understood Pakistan’s national security threats and the frustration felt by the country’ military leadership about not having a say over the drone strikes.

Grenier, who was posted as the CIA’s Islamabad station chief from 1999 to 2001, was present in the country during the World Trade Centre attacks on September 11, 2001. Describing the intelligence cooperation between Pakistan and the United States before 9/11 as “very limited”, Grenier says that after President Musharraf’s decision to ally with the United States, “the relationship with the intelligence agencies changed from virtually no cooperation to full co-operation, at least with respect to al Qaeda.”

In an interview last year, Grenier said he believed Pakistan did not know where Bin Laden was. Does he still stand by that statement, months after Bin Laden was discovered in Abbottabad?

“My strong suspicion even now is that no one other than the close collaborators of Bin Laden knew that he was in Abbottabad. No one has apparently found any compelling evidence that there was any official knowledge on the part of Pakistan of Bin Laden’s whereabouts. I continue to believe that they were as surprised as anyone when he turned out to be hiding in Abbottabad.”

Bin Laden’s trail, says Grenier, went cold “essentially after he apparently escaped from the Tora Bora area around December of 2001. As I even said at the time, for all we knew, he could’ve been hiding in a small apartment somewhere in Karachi.”

While Grenier declined to talk about details of the drone program that began under his watch, while he was head of the CIA Counterterrorism Centre in 2004, he offers his insights on the effects of the drone program.

“In the early days, the missile strikes seemed to be limited to the very senior cadre of al Qaeda. In more recent years, it appears that the targets of missile strikes have included much larger number of local fighters – Afghan and Pakistan fighters. It seems to me that it has become much more of a conventional weapon against militants as opposed to a very surgically employed tool against international terrorists.”

Grenier seemed quite understanding of Pakistani frustrations about the programme, but also justified the US strategy behind them.

“Putting myself in the position of my former counterparts in Pakistan, it must be frustrating given the fact that the Pakistanis have to deal with the effect of these strikes, without really having any vote in terms of how these strikes are employed. The American point of view is that it is Pakistan’s responsibility to not let its territory to be used as a base for militants. Given the apparent inability of the Pakistanis to control the tribal areas, [US officials] feel great pressure to do something about it unilaterally.”

Grenier talks about the rifts in relations between the United States and Pakistan as a divergence of their national interests.

“The fundamental problem between the United States and Pakistan right now is that they don’t see their national interests as completely overlapping and in fact over time have been diverging. Pakistan is very concerned about the large US military presence in Afghanistan as a radicalising factor. The US, on the other hand, very much wants Pakistan to address this issue because it imposes a direct threat to US and NATO and Afghan forces. Politically, Pakistan is concerned about an essentially unfriendly government in Kabul with very close relations to India, an issue that the US is very reluctant to address.”

Grenier advises US policymakers to put themselves in their Pakistani counterparts’ shoes before making decisions about the region. He also asks Pakistanis to get more serious about the problem of militancy, which he says is not as dependent on the US presence in Afghanistan as many in Islamabad would like to believe.

“Militancy within Pakistan is not going to go away and I think the drawdown of the US presence in Afghanistan is not going to cause that threat to diminish appreciably,” he said.

Published in The Express Tribune, August 28th, 2011.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ