Every now and then, some isolated case of honour killings makes its way to the media. However, beyond individual tragedies lies a bleak national picture, where family forgiveness, judicial delays, and weaknesses in law enforcement allow innocents to continue being killed in the name of honour.

Honour killings continue to emerge as a serious human rights issue across the country, where the number of incidents remains high while the rate of convictions is miserably low. A recent report by the Sustainable Social Development Organisation (SSDO), supported by official records and international studies, reveals that weak investigations, judicial delays, and social pressure continue to hinder the road to justice despite the existence of a legal framework.

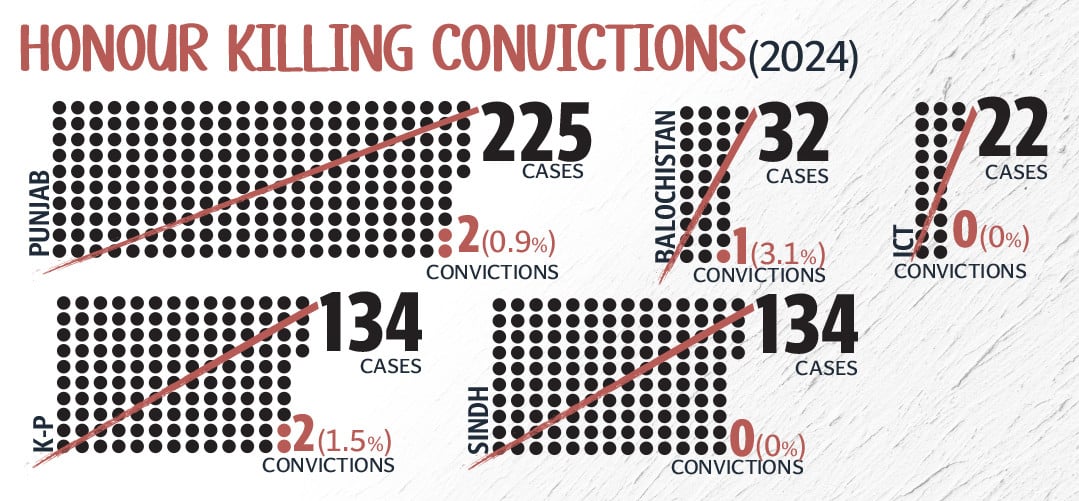

Punjab reported the highest number of honour killing cases, with 225 incidents in which only two convictions were secured. Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa (K-P) recorded 134 honour killings, also resulting in just two convictions. Sindh reported honour killing cases but saw no convictions. Balochistan documented 32 honour killings, with only one conviction. Across these provinces, the data highlights a glaring gap between the number of lives lost and the delivery of justice.

Social activist Imran Takkar, working on women’s rights, told The Express Tribune that 90 per cent of honour killing victims were women. “Women are already considered a weak and oppressed segment of society, and families often withdraw in such cases. If the police builds stronger cases, investigations are conducted in an improved manner, and prosecution plays its role, harsher punishments are possible,” noted Takkar.

Senior Advocate Shabbir Hussain Gigyani opined that while laws and amendments existed, poor police investigation and weak case-building remained key hindrances. “Police often make close relatives of the victim complainants and witnesses, who later reach compromises with the accused. Witnesses then retract statements before trial, leading to acquittals in about 80 per cent of cases," said Gigyani.

SSDO Executive Director Syed Kausar Abbas stated that the extremely low conviction rate indicated that the existing system had failed to provide effective protection and timely justice to victims. “Immediate reforms are essential to strengthen police investigations, improve legal procedures, and ensure speedy trials,” emphasised Abbas.

Victims of customs

Rooted in deeply entrenched customs, the practice of honour killings weaponises fear to violently silence those challenging social boundaries for good. Therefore, in the absence of strict law enforcement, victim's deaths continue to be rationalised as moral correction, allowing accountability to remain elusive.

For instance, in K-P, where preserving honour is often considered a matter of life and death, honour killings are a dark secret of the local culture and could not be eliminated despite existing laws. On December 17, 2025, in Upper Dir district, a brother shot his sister and a man after seeing them talking together.

A case was registered at Thana Patrak, Dir Upper, under murder and honour killing provisions, including Section 311 PPC. District Police Officer (DPO) Dir told The Express Tribune that all legal aspects were fulfilled. “Even if the complainant forgives, punishment cannot be waived due to strict provisions. The accused was arrested on the third day,” said the officer.

However, in dozens of cases, only Section 302 is applied, resulting in weak charges and allowing the accused to be released quickly. In the summer of 2025, a young man was killed in Peshawar’s Chamkani area because he refused a relationship with another man. Even though the killer cited honour to be his motive, honour killing provisions were not included.

In K-P, not only women but also young men and transgender persons are victims of honour killings. On December 2, 2025, in the Charsadda Road area of Peshawar, a transgender person named Bijli was killed by a former partner for talking to and meeting someone else. Here, too, only Section 302 was applied. On May 28, 2023, a girl was murdered by her father and brother. The perpetrators attempted to secretly bury her inside the house. However, the police were alerted in time and the accused were arrested.

Although sections related to honour killing were included in the case, the perpetrators were released soon afterwards due to the absence of eyewitnesses and the failure of the state to register the case independently. Another tragic incident was reported on January 16, 2021, involving a student, Taha Alam, from the Mandani area of Charsadda. Alam was allegedly shot dead by a man identified as Owais for the sole reason of talking to his cousin.

According to K-P Police data obtained by The Express Tribune, 160 honour killing incidents were reported across the province in 2025 alone. Approximately 135, or 75 per cent of the victims killed in the name of honour, were women. Cases were registered against 374 individuals, and 258 accused were arrested. In 2024, 159 people were killed in honour-related incidents, including 139 women. Out of 390 nominated accused, 332 were arrested.

Senior Superintendent of Police (SSP) Investigation Peshawar, Ayesha Gul, told The Express Tribune that resolving gender-related cases and punishing perpetrators according to law was a top priority. “The K-P Police Gender Unit is actively working, and the investigation department is being equipped with modern technology to reduce investigative flaws and improve legal assistance to complainants,” said Gul.

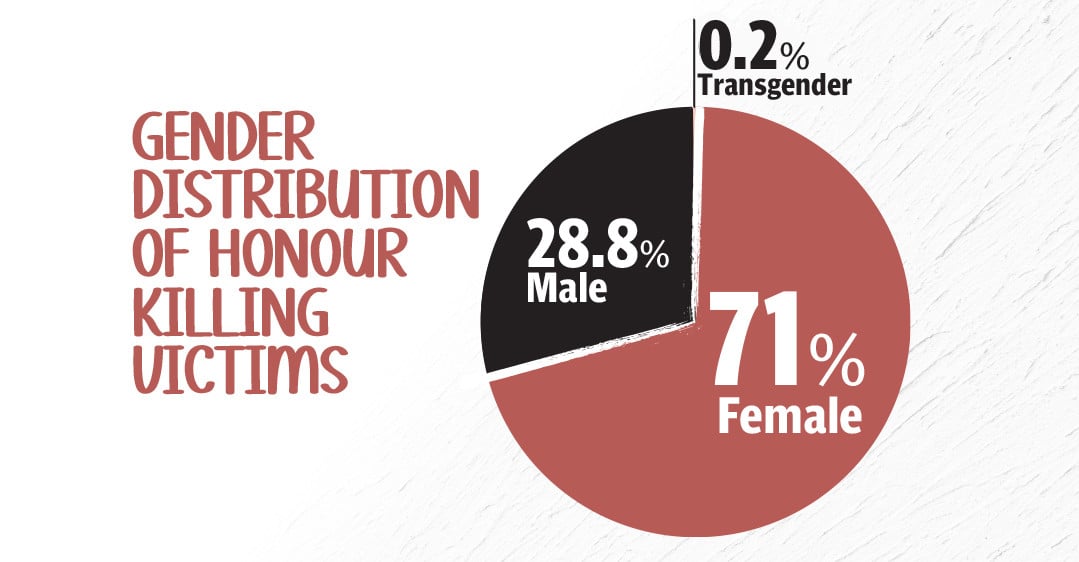

According to the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan’s 2024 annual report, women are the primary victims of honour killings. A 2020 report showed that out of 511 incidents, 363 women and 148 men were killed – that is 71 per cent women and 29 per cent men.

One reason for the higher proportion of women was that in many cases multiple women were killed in a single incident. For example, in October 2024 in Karachi’s Lea Market area, an accused named Bilal killed four women at once: his mother, sister, niece, and sister-in-law. In September of the same year, in a village in Nawabshah, a man killed his two sisters in the name of honour.

Grim national statistics

An NGO’s 2024 report on gender-based violence stated that incidents of rape, domestic violence, and honour killings increased alarmingly across Pakistan, while conviction rates remained extremely low. In 2024, 32,617 gender-based violence cases were reported nationwide.

According to the report, 5,339 rape cases and 24,439 abduction cases were reported; 2,238 cases of domestic violence and 547 honour killings were recorded. Conviction rates were barely 0.5 per cent for rape and honour killings, 0.1 per cent for abduction, and 1.3 per cent for domestic violence.

Punjab reported the highest number of cases, 26,753, with only two convictions out of 225 honour killing cases. K-P reported 3,397 cases and 134 honour killings, with only two convictions. Sindh reported 1,781 cases, with zero convictions in honour killing, rape, or abduction cases. Balochistan reported 398 cases, with just one conviction in 32 honour killings, and none in 21 rape cases. Concurrently, Islamabad reported 220 cases of gender-based violence and 176 rape cases, with only seven convictions.

According to the NGO’s report, K-P recorded 134 honour killings, with only two convictions, reflecting a conviction rate of 1.49 per cent. Experts have cited investigative flaws, witness intimidation, out-of-court settlements, and social influence as factors allowing perpetrators to escape.

Reports indicated that most honour killing cases in Punjab were registered under Section 302 of the Pakistan Penal Code as ordinary murder. In many cases, the motive of honour was not clearly mentioned in the FIR, causing such cases to be counted as simple murder in official statistics and limiting the application of specific honour killing laws.

Official records further showed that from January to June 2025, an additional 89 incidents of honour killing were reported in the province. Of these, challans were submitted to courts in 80 cases, while 10 cases remained under investigation; 70 were under trial, and one case was withdrawn. During these six months, not a single case resulted in a conviction.

At the international level, a 2022 report by the European Union Agency for Asylum described honour killings in Pakistan as crimes carried out under practices such as karo-kari, siyah-kari, and similar traditions. The report stated that although the concept of honour appeared gender-neutral, in practice, the majority of victims were women.

According to the document, female victims constituted a significantly higher proportion of reported honour killing cases in Pakistan, while many incidents in rural areas went unreported due to social pressure and informal systems.

A report citing the Punjab Commission on the Status of Women stated that between 2019 and 2020, honour killing incidents in the province increased by 20 per cent, while the conviction rate in these cases was only 5.4 per cent. Experts believed that this worrisomely low rate raised serious questions about the effective enforcement of the honour killings law.

Laws under trial

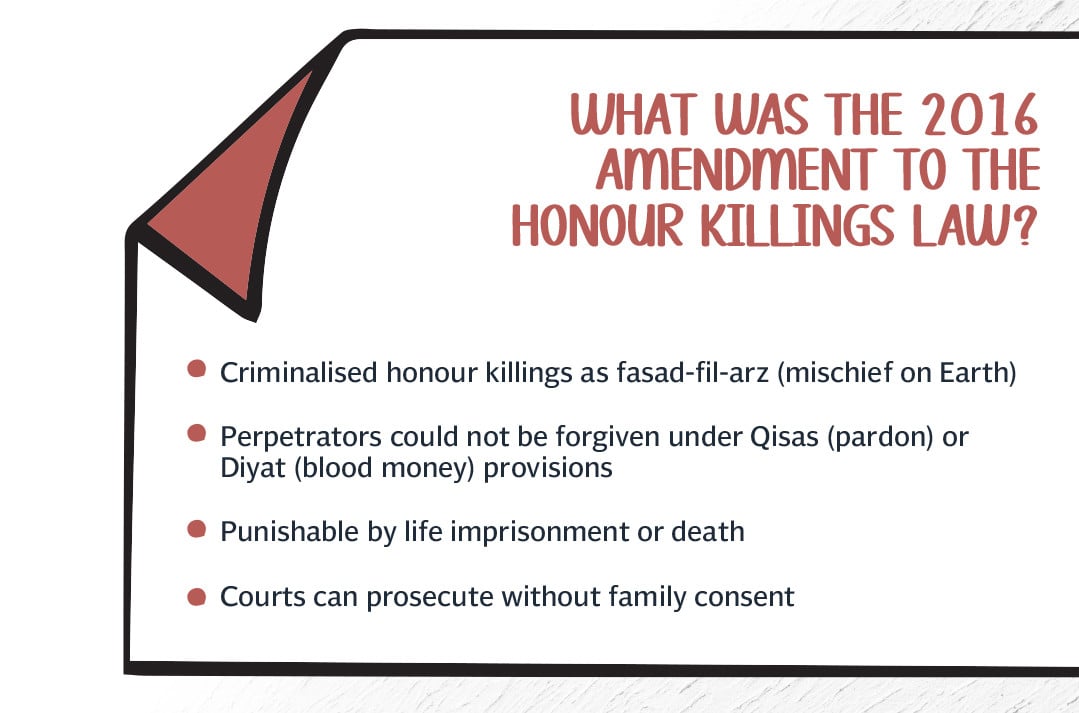

In 2016, Pakistan amended its criminal law to curb honour killings by closing the loophole that allowed perpetrators to escape punishment through family forgiveness (qisas and diyat). Under the amendment, honour killings were termed “fasad-fil-arz” (mischief on earth), empowering courts to impose mandatory life imprisonment even if the victim’s heirs pardoned the offender.

The reform aimed to make such cases non-compoundable in practice, reduce family pressure-based compromises, and strengthen the state’s responsibility in prosecuting these crimes. However, weak implementation, continued compromises, and evidentiary failures have limited its impact. Unfortunately, the amendment was not implemented in spirit, which is why it has yet to yield practical benefits.

After the amendment, legally, there was no room to pardon the accused in honour killing cases, yet offenders continue to escape punishment because legal loopholes often shield them. Local lawyer Advocate Muneeza Kakar explained that after the amendments to the Pakistan Penal Code (PPC), honour killings became legally non-compoundable, with no provision for qisas or diyat.

“Despite this, accused persons still escape punishment through technicalities. Usually, both parties reach a compromise, and witnesses retract their statements in court, weakening the case and leaving the court with no option but to acquit the accused,” Kakar told The Express Tribune.

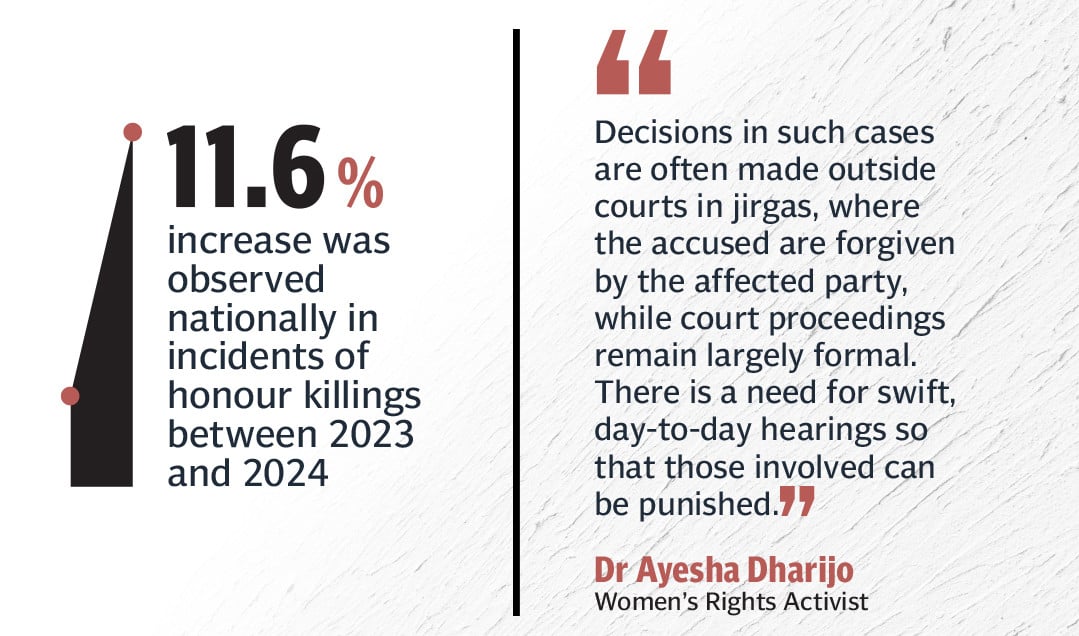

Dr Ayesha Dharijo, a women’s rights activist in Sindh, highlighted that police disinterest and the entrenched jirga system were also major factors allowing offenders to evade justice.

“Decisions in such cases are often made outside courts in jirgas, where the accused are forgiven by the affected party, while court proceedings remain largely formal. Swift, day-to-day hearings are needed so that perpetrators can be punished,” Dharijo noted.

Legal experts stressed that the 2016 amendment aimed to empower courts to declare such murders as fasad-fil-arz and award at least life imprisonment, even if heirs forgive the offender. Supreme Court lawyer Naseer Kamboh added that, in practice, qisas and family compromises, coupled with lack of witness cooperation, make convictions difficult in most cases.

“There is no reliable consolidated data on offenders in Punjab who have been pardoned under qisas, but these factors remain major reasons for the low conviction rate,” Kamboh said.

Reports indicate that in rural areas, delays in arrests, the influence of informal jirga systems, and family pressure result in many incidents going unreported, while in some cases, suspects are given the opportunity to flee.

When asked about poor conviction rates, Islamabad-based lawyer Ahsan Jehangir Khan said: “The conviction rate is poor because the sentiment of ‘honour’ killings being a ‘personal’ crime is hard to uproot. While this sentiment has changed in urban areas, rural areas remain largely unchanged. Whether urban or rural, once the investigation officer or prosecution views such heinous crimes as within a ‘family’ purview, the need to prosecute or secure a conviction diminishes.”

He cautioned that one cannot ignore how easily the criminal judicial system is influenced. “All it takes is one judge, one lawyer, or one police officer losing interest, and the entire case collapses. This disinterest can stem from money, familial ties, or simply the perception that it is a ‘personal matter,’” Khan explained.

Logic dictates that the state should automatically assume the role of complainant in such cases, but that rarely happens. This allows criminals to negotiate outside-court compromises. “There is no doubt it is the state’s responsibility to prosecute. Honour killing is inherently a crime against the state. However, if even one cog in the system fails to pursue the case, the system slows down, leaving those aggrieved to settle through pardons or private deals, which usually involve money,” Khan said. He added that state action often occurs only under pressure from social media, senior officials, or elected representatives.

During the interview, Khan was asked whether the continued use of Section 302, without the mandatory invocation of Section 311, affects fairness in honour killing cases—reducing them to private disputes under qisas and undermining the 2016 reform. He acknowledged that considerable progress had been made.

“Crimes motivated by honour do attract Section 311 of the Pakistan Penal Code. But if honour as a motive is not properly established—which links back to weak prosecution—Section 302 becomes the fallback,” he explained.

Asked about compromise deals allowing offenders to escape justice, Khan said: “I do not agree with the grey area the ‘compromise’ factor occupies in our criminal jurisprudence. Eliminating it entirely would require serious legislative effort and judicial restraint. Yet, because this principle involves interpretation of Islamic injunctions, we often end up in a dead-end.”

“The 2016 amendments were one such effort, but even in 2026, honour killings remain a reality, and low convictions are still the norm,” he concluded.

The collective view of experts and organisations is clear: despite the existence of a legal framework against honour killings in Pakistan, particularly in Punjab, low conviction rates, judicial loopholes, social attitudes, and weak implementation remain the fundamental obstacles blocking justice.