Even after three decades of aggressive eradication campaigns marked by public mistrust, Pakistan has failed to develop a government-run system for the treatment, rehabilitation, or long-term social integration of children already disabled by polio. As prevention through vaccination remains the state’s exclusive strategy, thousands of polio survivors silently carry the weight of paralysis.

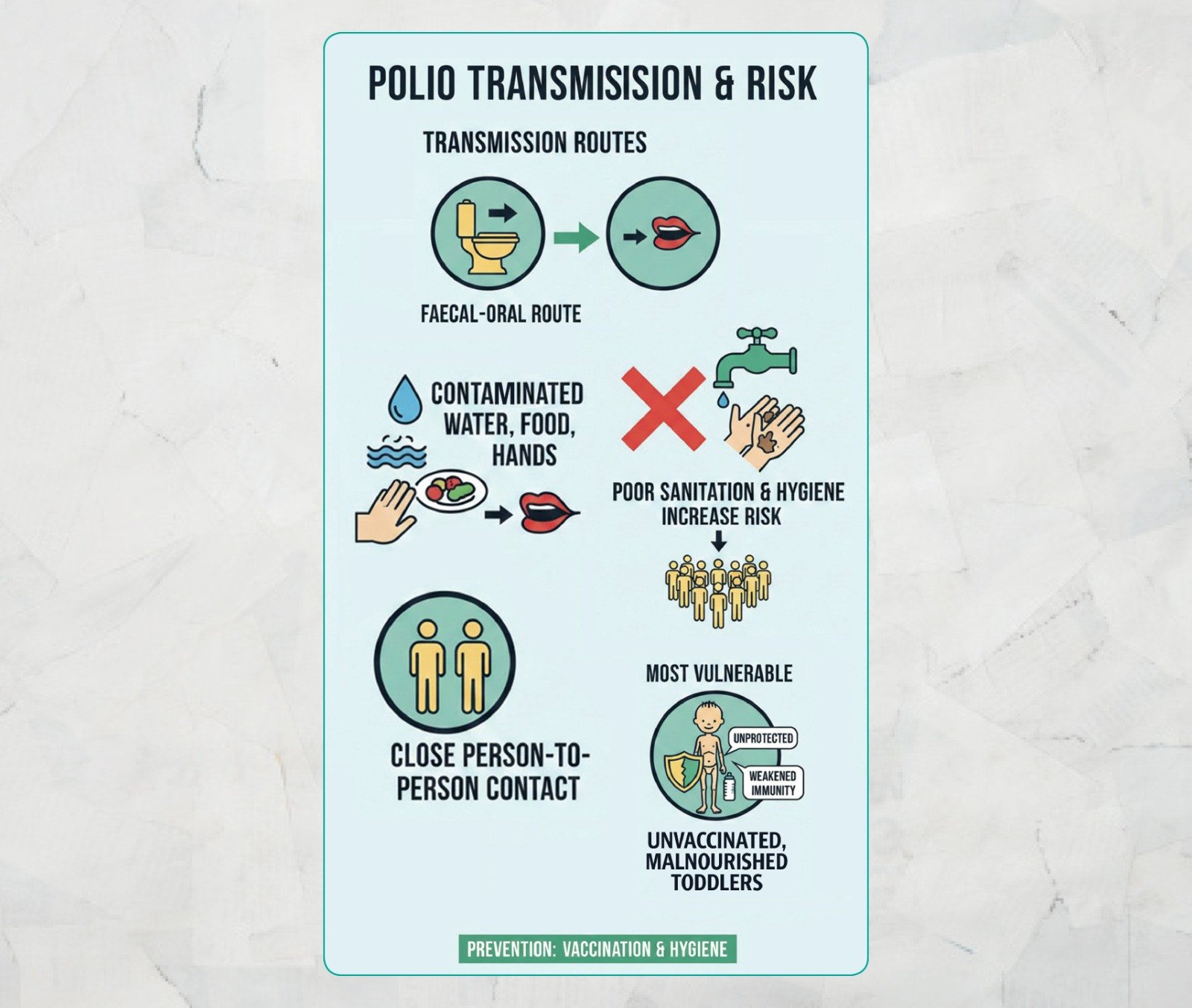

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), poliomyelitis also known as polio, primarily affects children under the age of five, attacking the nervous system and causing irreversible paralysis, most commonly in the lower limbs. Medical experts confirm that the disease is incurable: once the virus damages nerve cells, the resulting disability cannot be reversed through surgery, medication, or therapy. Children disabled by polio, therefore, face lifelong physical limitations, often accompanied by psychological distress, stigma, and social exclusion that intensify as they grow older.

Pakistan’s first national polio eradication campaign was launched in 1994 by then Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto, who administered polio drops to her daughter in Karachi. For the past 31 years, polio eradication campaigns have continued in Pakistan with support from the WHO, Unicef, and other institutions. Initially, the campaign operated under the Health Department, but it is now managed by district administrations. Between 1994 and 2025, Pakistan recorded a staggering total of 14,206 confirmed polio cases, creating a large but largely invisible population of survivors.

However, till date, the country lacks public rehabilitation centres, vocational training programmes, or psychosocial support systems tailored to polio survivors, forcing families to seek costly private care that many cannot afford. Without structured support, disabled children and adults are left vulnerable to neglect and exploitation, while facing persistent barriers to education, employment, and social participation. Given the patriarchal nature of the social system, for girls in particular, disability often reduces marriage prospects, reinforcing isolation and long-term insecurity.

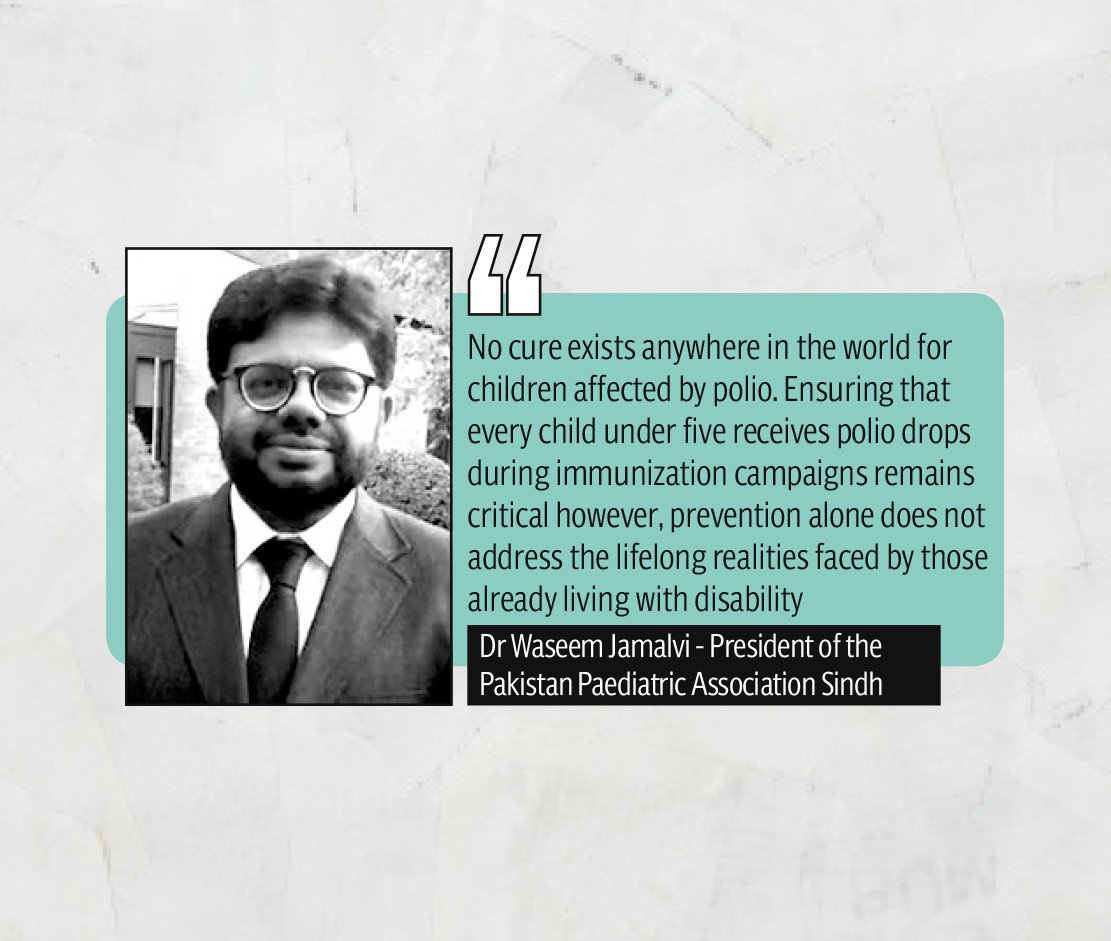

Professor Dr Waseem Jamalvi, a paediatrician at Dow University of Health Sciences and President of the Pakistan Paediatric Association Sindh, underscored that no cure existed anywhere in the world for children disabled by polio. “The virus impacts each child differently, but those with weaker immunity face a significantly higher risk of infection. Paralysis caused by polio cannot be reversed because the virus permanently destroys nerve cells. Ensuring that every child under five receives polio drops during immunisation campaigns remains critical however, prevention alone does not address the lifelong realities faced by those already living with disability,” noted Dr Jamalvi.

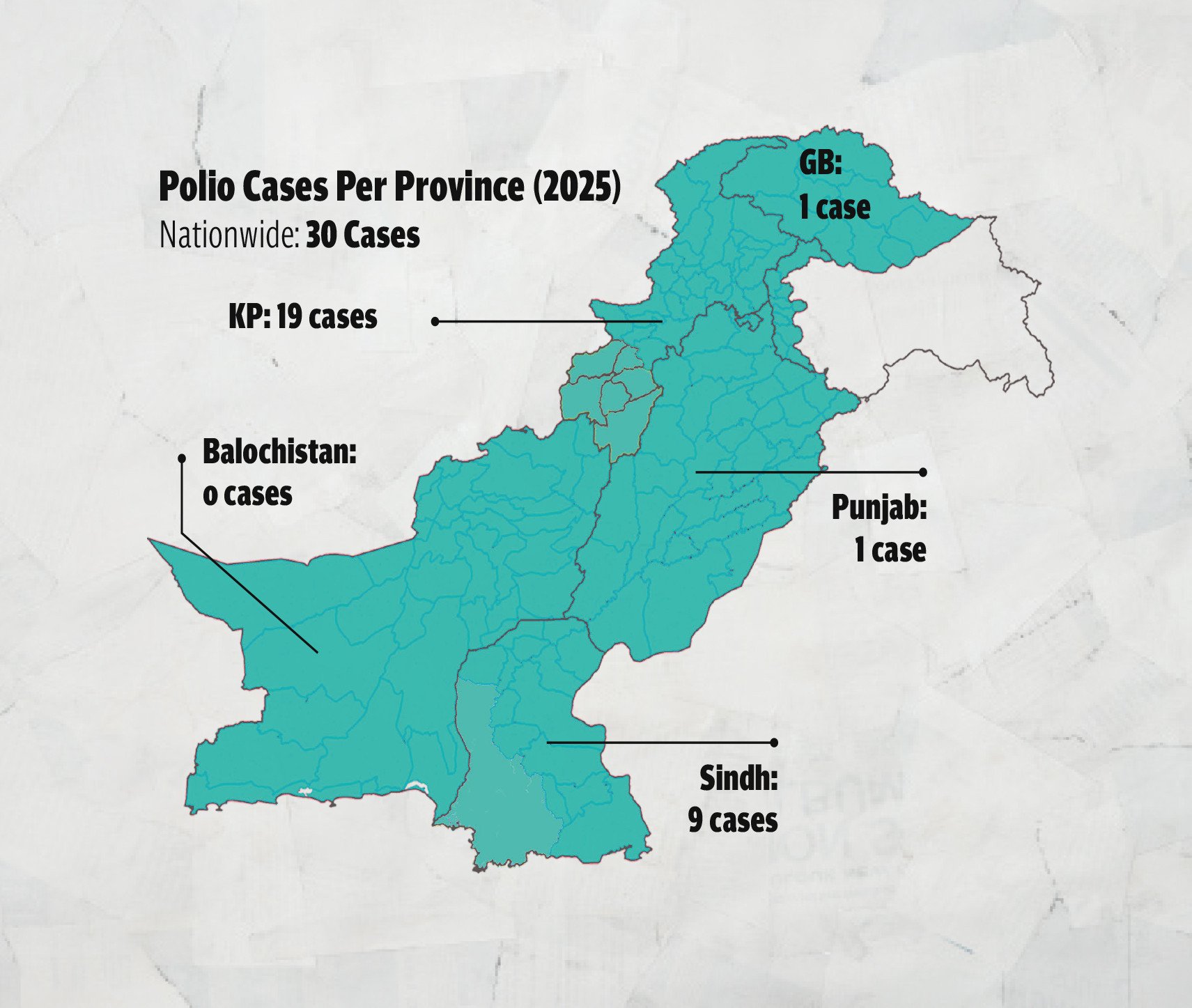

According to statistics from the National Emergency Operations Centre (NEOC), the highest number of polio cases, 2,635, was reported in 1994, after which a steady decline in cases was observed. In 2025, a total of 30 cases were reported from across the country, with the highest number (19) recorded in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa (K-P), nine recorded in Sindh, and one each in Punjab and Gilgit-Baltistan (G-B). In K-P, the worst affected province, the majority of cases originated from North Waziristan, Lakki Marwat, Tank, Dera Ismail Khan, Lower Kohistan, Torghar, and Bannu. Unsurprisingly, these are the same regions where vaccination attempts have long been marred by a lethal mix of foreign conspiracy theories and entrenched local resistance.

Vials of controversy

Despite decades of mass vaccination campaigns, polio continues to circulate in Pakistan, largely due to deep-rooted mistrust and persistent resistance to immunisation. In essence, the country’s eradication efforts are undermined by a combination of misinformation, political interference, and security challenges that have turned protective polio drops into vials of controversy.

Till date, vaccine hesitancy remains one of the biggest obstacles. In parts of K-P and Sindh, rumours persist that polio drops cause infertility or are part of a Western conspiracy. Public suspicion intensified after 2011, when the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) used a fake vaccination campaign led by a local doctor, Shakil Afridi, to locate the world’s most wanted terrorist, Osama bin Laden, in Abbottabad. While the mission was covert, its consequences were long-lasting as families became wary of health workers and began refusing vaccinations.

Experts are of the opinion that this erosion of trust was one of the primary reasons leading Pakistan to remain among the only two countries where polio is still endemic. Apart from this, security threats have also compounded the problem. Since the 1990s, more than 200 polio workers and their security escorts have been killed in militant attacks. These attacks have not only disrupted immunisation drives but have also created fear among frontline workers and their families, slowing progress and increasing the number of children missed during vaccination campaigns. Even in urban centres, teams face resistance fuelled by rumours and local scepticism, highlighting that the challenge is not only logistical but also social.

Experts also point to weaknesses in communication and outreach strategies. While billions of rupees have been spent on vaccination campaigns, public awareness efforts often fail to address local concerns or involve community leaders. Dr Farman Ali, a public health specialist in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, felt that without sustained community engagement and trust-building, polio would continue to exist, no matter how many vaccines were delivered. “Environmental surveillance has shown that the virus persists in sewage samples across multiple provinces, signalling that incomplete coverage and social resistance are keeping the virus alive,” said Dr Ali.

“Even as polio has been eliminated in Yemen, Sudan, and several African countries, Pakistan struggles with inconsistent strategies, insufficient local trust, and logistical gaps. In this scenario, building confidence in vaccination, addressing misinformation, and protecting frontline workers are as critical as the vaccines themselves,” said Dr Ali, who believed that without tackling these social and political barriers, eradication will remain an elusive goal, leaving the country to contend with the ongoing human and financial cost of a preventable disease.

Expanding on the problem, a senior official associated with the K-P polio programme stated that while governments and international funding agencies continued to invest heavily in prevention and vaccination, little attention was paid to the long-term needs of those already affected by the virus. Syed Muhammad Ilyas, Chief Executive of the Paraplegic Centre Hayatabad, revealed that his organisation provided wheelchairs and basic rehabilitation services to more than 2,020 polio-affected individuals, yet there was no specialised centre in the province dedicated exclusively to polio survivors.

“Whenever a polio case is reported, the news spreads within seconds across all platforms. But after that, no one asks what will happen to the affected child or what their future will be,” said Qari Saad Noor, a person with disabilities and President of the Special Persons Association Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. According to reports and data from the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics for 2023–2025, the prevalence of disability in K-P stands at approximately 3.2 per cent of the estimated population of nearly 40 million.

Disabled by stigma

Disabled by stigma

People with disabilities often navigate a world that overlooks their intellectual potential in light of their physical impairment. As a result, polio survivors, especially young girls, face daunting obstacles in accessing education, pursuing careers, and forming families, leaving them isolated, socially marginalised, and, in many ways, disabled by stigma.

Ayesha, the mother of a polio-affected girl from Gadap, revealed that her daughter, now 16 years old, had been living with disability since 2009 due to polio. Narrating her painful journey, Ayesha shared that her daughter was only a toddler when her lower body suddenly became paralysed. After medical examinations and tests, it was confirmed that she had contracted polio.

“All possible treatments were attempted, but doctors declared the disease incurable. Along with physiotherapy, traditional treatments were also tried, but without success,” said Ayesha. “Due to disability, my daughter suffers from depression and is undergoing treatment. She walks with crutches at home and could not continue her education beyond eighth grade. The family now faces severe mental stress regarding her marriage prospects,” she said.

Similarly, 48-year-old Azhar was affected by polio in childhood. He could not remember the exact age he contracted the disease, but his parents told him he was three years old at the time. Due to polio-related disability, Azhar faced severe difficulties in education, employment, and marriage despite wanting to move ahead in his life. Although he continued his education privately, he avoided social interaction, hesitated to attend gatherings, and suffered from feelings of inferiority when seeing healthy individuals.

“Due to my disability, I could not secure employment or manage life independently,” Azhar said. “The personalities of boys and girls affected by polio do not fully develop, and they lack confidence during their education. Such children suffer from an inferiority complex, their mental development is affected, and their abilities become limited.” He continued, “I would urge the government to take concrete steps for polio rehabilitation and to allocate job quotas for polio-affected individuals.” Azhar stressed that polio drops were essential for every child since even a minor negligence could ruin their whole life.

Waseem Khan, a person with disabilities from the Gulbahar area of Peshawar, also shared his concerns with The Express Tribune. He said thousands of girls and women with disabilities face neglect and exclusion, as no one is willing to take responsibility for helping them become productive members of society. “Families with financial means can arrange rehabilitation and treatment for their children affected by polio. But what about the poor? Those who cannot afford treatment are confined to their beds. Who will ask about them?” he asked.

Khan urged the government and donor agencies to establish a well-equipped, specialised rehabilitation centre for polio affected persons, stressing that empowering this segment of the population would enable them to contribute meaningfully to the country.

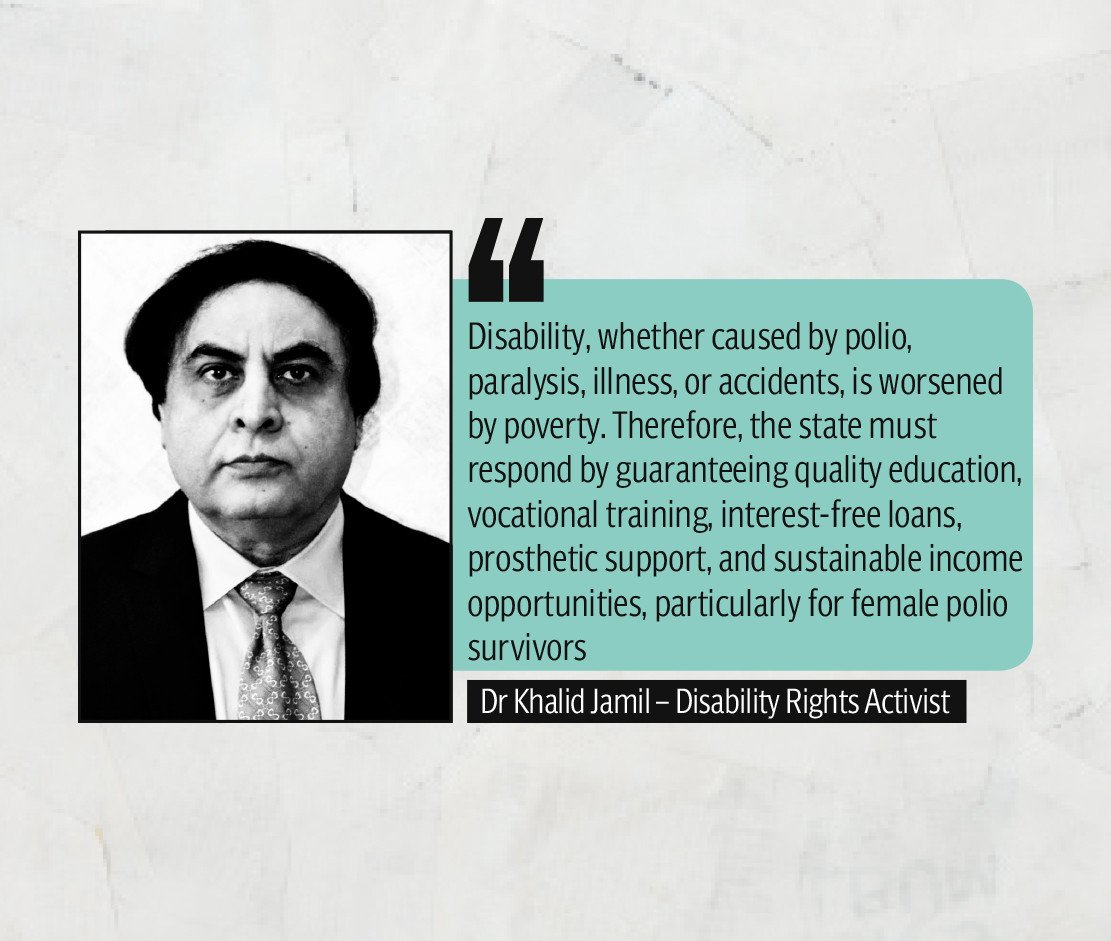

Dr Khalid Jamil, a disability rights advocate implored that disability, whether caused by polio, paralysis, illness, or accidents, was worsened by poverty. "Limited mobility reduces employment opportunities, doubling economic hardship. Therefore, the government must provide vocational training, interest-free loans, and enforce the three-percent employment quota," Dr Jamil said.

“In addition to this, it must also offer free education, supply prosthetic limbs, and create income-generating opportunities, especially for women, including online work and teaching. With proper support, polio-affected individuals can become productive members of society and contribute across various professions,” emphasised Dr Jamil, who himself is a polio survivor.

The road ahead

While Pakistan has made progress in reducing case numbers over the years, persistent outbreaks and the virus’s continued presence in environmental samples highlight the gaps that remain. The road ahead is not just about preventing new infections but also about finally breaking the cycle of fear, misinformation, and neglect.

According to Adeel Tasawur, Head of the Polio Programme in Punjab, the province had demonstrated strong population immunity and operational effectiveness. “Last year, barely two polio cases were reported in Punjab, both with low clinical severity,” claimed Tasawur. However, this paint only a partial picture of the polio situation across other areas of the country, where socio-historical and cultural barriers thwart vaccination efforts.

“K-P remained the primary hotspot, accounting for 19 cases, while Sindh recorded a rise in infections. The virus was also detected in Punjab and Gilgit-Baltistan. Despite more than five decades of vaccination campaigns, Pakistan remains one of only two countries in the world where polio is still endemic, and inconsistent strategies have pushed the goal of eradication further out of reach,” explained Dr Mohammed Hussain, Pakistan Paediatric Association's Vice President for K-P.

Former District Health Officer Dr Farman Ali, revealed that nearly 40 percent of children in K-P suffered from malnutrition, making them more vulnerable to infection. “The K-P Health Department and donor-supported polio eradication programmes have failed to build sustained public trust in vaccination, allowing the virus to persist. Polio has been eradicated in other nations, while Pakistan and Afghanistan remain the last two affected countries. Although some progress has been made, major gaps remain, especially since water in Peshawar continues to be contaminated and environmental samples still detect the virus,” said Dr Ali.

On the other hand, Associate Professor Dr Ali Faisal Saleem, Vice Chair of the Child Health Department at the Aga Khan University Hospital (AKUH), urged that Pakistan’s efforts to eliminate polio were plagued by the fact that vaccination coverage for preventable diseases was still uneven.

“Although Punjab performs comparatively better in terms of vaccination coverage, Sindh lags behind. There is a dire need to identify high-risk areas through environmental and sewage surveillance, since several sewage samples in major cities have tested positive. Polio cases continue to emerge because children missed during campaigns are not reached, while already vaccinated children receive repeated doses,” said Dr Saleem, adding that the vaccine was effective yet access, awareness, and parental consent remained the real challenges.

Dr Ali reiterated that despite billions of rupees allocated to polio eradication efforts, K-P had no specialised rehabilitation centres for individuals already disabled by the disease. On the contrary, Polio Operations Centre Coordinator Shafiullah Khan clarified that the establishment of polio rehabilitation centres fell under the responsibility of the Health Department and the Social Welfare Department, not the polio eradication programme.

“The polio programme must urgently reform its communication and community engagement strategies to rebuild trust. Without meaningful public confidence and inclusive long-term planning, polio will continue to circulate in Pakistan,” warned Dr Ali.