I'm not a botanist but rather an amateur naturalist, captivated by the myriad aspects of nature that surround me. Despite not being an astronomer, the Big Bang and the celestial elements it birthed are intriguing. I am not an architect but understand its fundamentals and have designed a few houses. While I am not a mathematician, I know its basics. What I didn’t know is that common to these diverse fields is a symbol of mathematical elegance and aesthetic perfection called the Golden Spiral.

I became aware of it some years ago while I was staying in our cottage in the mountains. My wife likes collecting a variety of cones, and I noticed that their woody scales and bracts, arranged around a central axis, were in two spirals that ran in opposite directions from the cone's base to its tip. I ran a search on Google, and that is when I became aware of a 13th-century Italian mathematician known by the pen name Fibonacci. He deciphered a simple sequence of numbers that explains this arrangement mathematically. Starting with the number one, simply add the previous two numbers in the sequence to generate the next one, e.g. 1+1=2, 1+2=3, 2+3=5, 3+5=8, 5+8=13, 8+13=21, 13+21=34, and on to infinity.

I counted the number of spirals in the pinecone and found 13 parallel spirals running gradually in one direction and 8 parallel spirals running steeply in the opposite direction. I learned that pinecones can also have 5 gradual and 3 steep, or 8 gradual and 5 steep spirals, and they, along with the above, are consecutive Fibonacci numbers. I also learned that similar forms of spiralling occur in shells like the nautilus, and fruits and plants like the skin of pineapples, the outer petals of artichokes, and the seeds of sunflowers, to name a few.

On an impulse, I picked one of the daisies growing wild in the garden, but I couldn't decipher a sequence in the arrangement of its 34 petals. However, when I looked harder, I found that the florets at the centre were arranged in a distinctly spiral pattern. On the internet, I found an enlargement with an accompanying diagram that showed that the florets had an arrangement of 21 spirals toward the right and 34 toward the left. Again, they were consecutive numbers from the Fibonacci sequence. It then struck me that the 34 petals of the daisy also corresponded to a Fibonacci number. I again went out and picked a buttercup and counted 5 petals, again a consecutive number from the sequence. The petals of some varieties of lilies and roses also follow this sequence, but it is not a universal phenomenon in either seeds or petals.

By now, I was well hooked on further exploring the Fibonacci sequence and found an exciting development. The consecutive numbers that appear in the Fibonacci sequence can be represented by fractions: 5/3, 8/5, 13/8, etc. When these fractions are converted into decimal numbers, a very interesting outcome occurs. In each case, the result is approximately 1.6, and as the numbers in the fractions increase in value, the ratio settles at 1.618. This ratio has had many names. Euclid, the Greek mathematician, called it the ‘extreme and mean ratio’, because it is associated with a specific mathematical relationship. Muslim scientists referred to it as ‘the middle and extreme proportion’, and it appeared in geometric patterns like the pentagon/pentagram used in decorating buildings. During the Renaissance, the sequence was referred to as the ‘divine proportion’, but it was as late as the 19th century that German mathematicians began using terms like ‘Goldener Schnitt’ (golden section), and ‘Golden Ratio’ came into common use. In 1909, Mark Barr, an American mathematician, proposed using the Greek letter φ for the Golden Ratio. His choice of the letter phi was to honour Phidias, a master Greek sculptor whose works, like Athena Parthenos and Zeus at Olympia, excelled in harmonious proportions.

Interestingly, honeybees have been observed to approximate the Fibonacci sequence in the ratio of the number of males to females. If you divide the number of females in a colony by the number of males (females always outnumber males), the answer is very close to 1.618. Every person’s body is different, yet when examined across large populations, certain human proportions have been observed to approximate Fibonacci-related ratios. An example that is often cited is the relationship between the distance from the navel to the floor and from the navel to the top of the head. In some studies, it has been observed to lie close to the Golden Ratio. Similar relationships exist within the human arm—such as between the tip of the middle finger and the wrist, the wrist and the elbow, and the elbow and the shoulder. The ratios are not exact, but they illustrate how human proportion may align with mathematical patterns found in nature.

At this point, the Golden Ratio transcends from mathematical elegance to the aesthetic perfection of the Golden Spiral. When these numbers are connected geometrically, they give birth to a visually stunning curve that is easy to draw with a ruler, pencil, and compass. Select the first six numbers of the sequence—1, 1, 2, 3, 5, and 8. Draw two adjacent squares of 1 inch each and attach a third square with sides of 2 inches. Adjacent to the sides of the 1- and 2-inch squares, attach a square with sides of 3 inches, and then attach squares of 5- and 8-inch sides, as shown in the diagram. Now draw a curve through the two 1-inch squares and extend it through all the other squares to form a spiral shape. Congratulations—you have drawn the Golden Spiral.

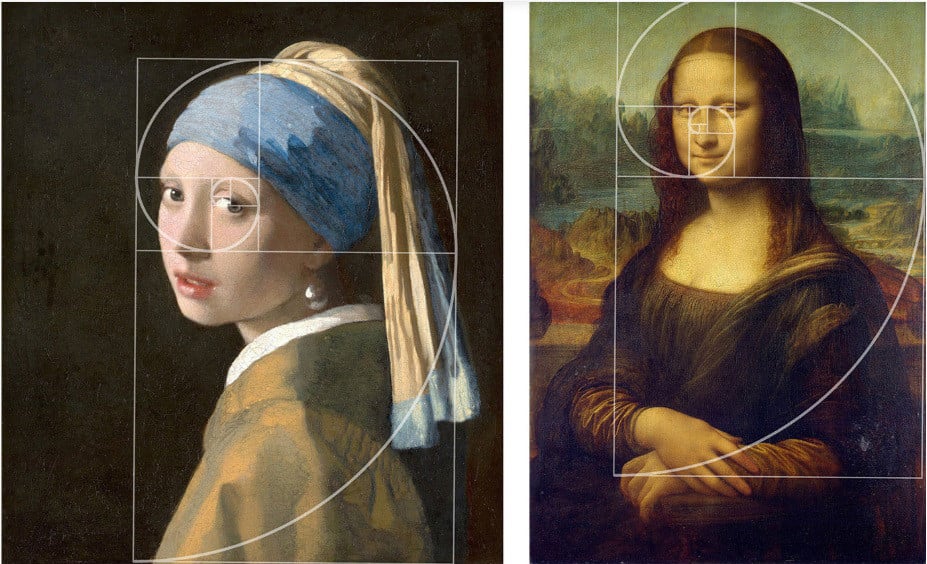

What makes the Golden Spiral so captivating is that its proportions are found not only in nature but are also, whether consciously or intuitively, applied by artists, architects, painters, and others. An excellent example of it in art is the iconic print called The Great Wave off Kanagawa, painted two centuries ago by Hokusai, a famous Japanese artist. Some other famous paintings that incorporate the divine proportion are The Starry Night by Vincent van Gogh, Girl with a Pearl Earring by Johannes Vermeer, Windmills by the painter Jacob van Ruisdael, and Madame X by John Singer Sargent. The artists may not have been aware of the Golden Spiral, but their works of art are balanced and aesthetically pleasing because they encapsulate it.

Historically, the Fibonacci sequence has been used by architects in designing structures. The Great Pyramid of Giza, built around 2560 BC, has been interpreted by some scholars as approximating the Golden Ratio. The length of each side of the base is 756 feet, and the height is 481 feet, and the ratio of the base to height, i.e. 756/481 = 1.5717, is close to the Golden Ratio. I have mentioned how the ratio appears in geometric designs used in Islamic decoration. The patterns of the Alhambra, which are among the most mathematically sophisticated Islamic geometric decorations, were constructed from overlapping pentagons and decagons. Leonardo da Vinci’s designs of churches and cities constantly employ harmonic proportions that approximate the Golden Ratio. Many of the major elements—such as the overall plan, dome diameter, drum height, and chapels—are set in proportional ratios of 1:2, 2:3, 3:5, and so on. Da Vinci worked closely with Luca Pacioli, a friar and mathematician who was known for linking mathematics, art, and proportion, and who wrote a philosophical and mathematical study of the Golden Ratio.

While researching this article, I also became aware that many composers have shown proportions aligned with the Golden Ratio. Béla Bartók stands out as the clearest and most convincing case of deliberate musical use of φ and structured some of his music around it. I do not claim to read musical scores, but in the first movement of Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta, Bartók places the central climax almost exactly at the Golden Ratio point, making φ the structural hinge of the form. Other examples include the first movement of Mozart’s Sonata No. 1 in C Major, Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, works by Erik Satie, and the Sonneries de la Rose+Croix.

Like the decorative patterns on Islamic buildings, Islamic calligraphy also placed a strong emphasis on precise geometric construction and proportional relationships. The straight, angular forms of Kufic were gradually replaced by the Thuluth script of curved and oblique lines, and the Golden Ratio can be found in every single letter or detail of the script. The Golden Ratio was also used by Arabs during medieval times in illustrations. Two manuscripts from the 14th and 16th centuries have similar two-dimensional illustrations based on the Golden Ratio. A well-researched article on the structure of illustrations in Islamic manuscripts by Safaa Jahameh from the School of Art and Design, Jordan, not only shows a number of these illustrations but also includes a picture of a Golden Ratio compass that was used to measure the ratio by Europeans and Arabs.

The widespread appeal of the Golden Ratio can be attributed to both its mathematical beauty and its pleasing proportion to the human eye, a fact hypothesised by psychologists such as Adolf Zeising. This has propelled its use in modern design and technology. Architects have translated this mathematical concept into physical form, creating buildings and spaces that are not only structurally sound but also pleasing to the human eye. An example of incorporating the Golden Ratio into modern architecture is the Guggenheim Museum in New York City. An overlay of the Golden Ratio on its design shows how its spiral, core, and wings align within a layered proportional system.

Architecture aside, a convincing example of the use of the Golden Ratio is in the design of smartphones and tablets. The proportions of many screens are close to the Golden Ratio because they create a balanced viewing experience. For instance, Apple’s iPhone incorporates the Golden Ratio in its icon layout grid and the dimensions of the phone, aimed at creating an appealing user interface and a comfortable grip. Similarly, in the world of PCs, the Golden Ratio is used to design keyboards and monitors. Microsoft has conducted research based on the principles of the Golden Ratio to ]create equipment that promotes a natural hand position.

In the automotive industry, manufacturers employ the ratio when designing the dashboard layout and even the proportions of a vehicle’s exterior. Aston Martin boasts of applying the Golden Ratio in the design of its latest DB9 and Rapide S automobiles. It describes the design of the Rapide S as: “Breathtaking Proportions –(because) The ‘Golden Ratio’ sits at the heart of every Aston Martin. Balanced from any angle, each exterior line of Rapide S works in concert and every proportion is precisely measured to create a lithe, pure form. Our engineering follows the same principle.”

The Golden Ratio is as much about mathematical harmony as it is about how humans perceive the beauty in shapes. Over centuries, humans have gravitated toward proportions that feel balanced and harmonious. Whether encountered in the composition of a painting, the curve of a staircase, or the geometry of calligraphy, these proportions echo patterns found in the natural world, from the spirals of a pinecone to the shapes of galaxies. The Golden Ratio may not be a universal law governing beauty, but it remains a bridge between mathematics, nature, and humanity’s perception of harmony in shapes and forms.

Syed Ali Hamid is a retired major general and military historian. He is also a heritage conservationist. He can be contacted at syedali4955@gmail.com.

All facts and information are the sole responsibility of the author