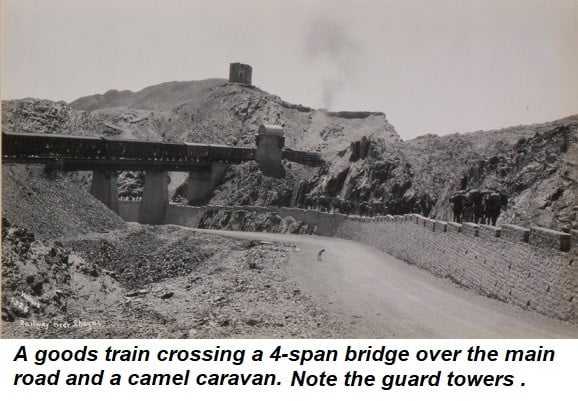

There are few railways in the world that can claim the romance and symbolism of the Khyber Pass Railway (KPR) that follows the contours of the Khyber Pass as it cuts through the Safed Koh Mountains. Over millenniums it was a highway for invaders, Sufi saints, spies, traders, adventurers’ nomads and caravans. When the Pass came under control of British India, it was picketed twice a week and camel caravans, some five miles long, would crawl from Landi Kotal to Jamrud in one long-days march.

Winding its way through barren mountains and guarded by pickets and forts, the KPR was more than a feat of engineering. When judged purely by engineering standards, the KPR does not match the other mountain railways in India. Its gradients are steep but not extreme; its altitude modest; its length short; and its traffic was always light. Yet despite these apparent limitations, the KPR carries a historical aura. While mountain lines like the Nilgri Mountain Railway and the Darjeeling Himalaya Railway charms with scenery; the KPR awes with the legacy of the historic pass that it penetrates through and the skill of those who built it — Britishers and Pathans.

A reconnaissance survey for the feasibility of a line through the Khyber Pass was conducted in 1879 by the North Western State Railway. during the Second Anglo-Afghan War. The prefix of ‘State’ indicated that the railway was owned by the Government of India unlike many other commercial railways in India which were privately funded and operated. For 20 years, the question of laying down a light railway on the route Peshawar-Landi Kotal & Nowshera-Dargai remained under consideration. During the closing stages of the Viceroyalty of Lord Lytton, a second survey for a narrow-gauge line was conducted to meet “the heavy demands for transport during military operations on the frontier.” The Great Game reached it pinnacle with the Panjdeh Incident in 1885 when Russian and Afghan troops clashed. It sparked a major diplomatic crisis between Russia and Great Britain and added impetus for the British to construct strategic arteries leading up to the border of Afghanistan. Though the North Western State Railway had reached Peshawar in 1883, all the major strategic railways built toward Afghanistan were on the axis of Quetta–Kandahar and the KPR remained ‘under consideration’.

The problem was that British control in the region of the NW Frontier was limited to fortified posts and cantonments, while much of the rest operated under tribal autonomy rather than formal colonial administration. The line only became a distinct possibility during the tenure of Lord Curzon (1899-1905) who established the NWFP as a Chief Commissioner Province, directly controlled by Delhi. The tribal agencies—Khyber, Kurram, Tochi, and the two Waziristan —were placed under powerful Political Agents like Roos-Keppel. They administered the agencies through an expanded Frontier Crimes Regulation, a deep understanding of tribal politics and were backed by a restructured, better equipped and larger Frontier Constabulary and the Khyber Rifles. In the settled districts, a lighter civil system operated, blending military and civilian authority in line with Curzon’s frontier philosophy.

An article appearing in the Daily Mail in Oct 1905 with the title Lord Kitchner's Khyber Railway said that without Viceroy Lord Curzon’s policy of peaceful penetration of the North West Frontier of India, “....... no such scheme [i.e. the KPR] could be conceivable in theory or practice.” The article concludes by saying, “Great things have been done for the world by the power of steam; but if it can unite Calcutta to Kabul its usefulness may have great political significance”. While uniting Kabul with the Indian Subcontinent would remain a pipe dream, the line did ultimately reach to the gates of Afghanistan. A short broad-gauge section was opened between Peshawar and Kachi Gari (a length of 7 km) on New Years Day in 1901 by no less a ‘superior person’ than the Viceroy who arrived by special train at the railhead. Curzon’s association with the adjective of ‘superior’ comes from a famous satirical verse composed by his contemporaries at Oxford mocking his aristocratic confidence and self-regard:

‘My name is George Nathaniel Curzon,

I am a most superior person.

My cheek is pink, my hair is sleek,

I dine at Blenheim once a week.

The ceremony was widely reported in The Pioneer and The Times of India, which recorded that the opening marked the beginning of Curzon’s broader strategy to strengthen the North-West Frontier through improved communications and streamlined administration.

Although Curzon had approved an extension toward Jamrud in 1901—and even ceremonially marked the beginning of the project—only minor works were carried out and no operational line existed. The scheme soon stalled due to many reasons including a lack of clear military necessity. Full construction resumed four years later, and between 1905 and 1907 the North Western Railway (the prefix of ‘State’ was dropped in 1895), laid approximately 32 kilometres of broad-gauge track from Peshawar to Jamrud. Work was suspended again after the Russo–British Convention of 1907 reduced the strategic urgency of penetrating the Khyber Pass. In fact, in 1909 several kilometres of permanent way and bridges were uprooted from and sent for use in other areas of India.

The outbreak of the Third Anglo-Afghan War of 1919 highlighted the vulnerability of relying solely on the existing road and prompted the British to restart and complete the railway project as a broad-gauge line that was capable of concentrating military force quickly at the western end of the Khyber Pass. As a temporary measure, a little-remembered aerial ropeway was constructed to supply the brigade in Landi Kotal and it was operated by the Khyber Ropeway Company of the Army Service Corps. It was erected on the same plan as a ropeway at Patriata erected in 1910 for bringing firewood to the troops at Murree. However, suffered chronic pilferage, with raiders lifting goods straight off the moving buckets. When construction of the KPR gathered pace in the early 1920s, much of the ropeway was dismantled.

Colonel Sir Gordon Hearn CIE, DSO, was one of the most accomplished railway engineers in India. He had participated in the Tirah Campaign, and the Second Afghan War and also served in France and Flanders during the World War I where he was awarded for gallantry. Back in India in 1920, he was assigned to survey and recommend a route through the Khyber Pass. Previously all surveys recommended a metre gauge line but Hearn who had worked on many railway projects, in one brief season surveyed and marked on a map a white line for a meter gauge railway. In the winter of 1920 Victor Bailey arrived in Peshawar as the executive engineer of the Khyber Railway Construction. Hearn was in Britian to purchase plant equipment and stores and Victor examined the plans for the whole railway line with tremendous interest. In his account ‘Permeant Way Through the Khyber’, he wrote, “The line rose from the mouth of the pass up a steep gradient and by means of a heroic zigzag to a place called Shahgai. The line curved too and fro and in one place actually crossed above itself in its serpentine progress. I feel an admiration for the boldness of the scheme... .”

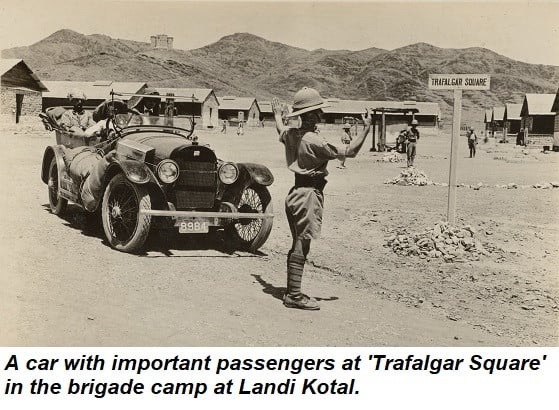

Victor established camp within the perimetre of a brigade at Landi Kotal and then reached out to the tribal Maliks without whose permission it would be impossible to lay a line up the Khyber. He also needed their willing participation to provide labour, stone masons, etc. A British officer had described the locals as ‘poisonous blighters’, but Victor developed his own impression. “Murderers and thieves, yes, but also men of this world.” Mir Akbar, the Malik of the Shinwaris settled around Landi Kotal owned two cars, read Reuter telegrams and could discuss Oriental politics intelligently and shrewdly. But Mir Akbar initially sat on the fence because he was afraid of involving his tribe with the Zaka Khel who were becoming more threatening in their negotiations. Victor went to meet Sher Ali Khan who he describes as a formidable Zaka Khel and a stout old ruffian who had been a VCO. He was warmly received, sat in a veranda with Sher Ali facing a large crowd of rough looking tribesmen, all armed, and exchanged pleasantries. However, when Victor broached the subject of permission to construct the railway, there was pin drop silence within the audience, then frowning his host said, “What folly is this? A railway through our lands!” accompanied by a menacing growl from the crowd and shouts of “Forbidden! Forbidden!”

Then occurred an incident that guided Victor in dealing with the tribals through the five years of construction—when in trouble tap on their boyish sense of humour. He had tried unconvincingly to tell the Zaka Khels of the many benefits of the railway: ease of communication, cheapening of food, etc. with no favourable response. Finally, he said to Sher Ali, “The trains will travel slowly...The Sultan Khel are notorious robbers and raiders. Think of the opportunities for looting the trains,” and then grinned. The host stared in astonishment and then lay back and laughed with tears in his eyes and when he translated it to the crowd, they too roared with laughter repeating “Build the railway and loot the trains.” This little joke never failed to cause a chuckle amongst the labour.

However, it was the lucrative labour contracts and agreements with the Maliks for safe passage {which included an additional allowance) that convinced the initially hostile tribes to participate. The contractors were recommended by the Political Agent and they organised and supervised their own labour gangs, provided escorts for mule convoys carrying gelignite and tools, and mediated disputes between workers and contractors. The Afridis sub-tribes supplied the largest contingent of workers for stone retaining walls, clearance of spoils from the tunnels, and donkeys. Around Landi Kotal, the Shinwaris contributed gangs skilled in hillside excavation and dry-stone work, while Yusufzai masons from the Peshawar Valley were hired for their expertise in shaping and setting the massive retaining walls that still survive today. The Maliks had no objection to Victor bringing in skilled craftsmen from outside — like blacksmiths, masons and brick moulders. Each contractor had his own camp with picquets and units of the Frontier Constabulary and Khassadars (levies) supplemented security. One report noted that “labourers went to work with a pickaxe in one hand and rifle in the other.”

Victors first critical task was to mark the centre of the line on ground which Hearn had only marked on the map. The alignment of the line seldom strayed far from the road but it was still no easy task to scramble up the steep slopes of shale that made climbing difficult. However, through all the six years of construction the ‘Khyber wind’ was one of the worst enemies. Victor recounts that, “Nearly every day a high wind blows; a solid stream of air pouring through the Pass like water over a weir. On the worst days it is practically impossible to move at all owing to the hail of sharp razor-like little chips of shale carried along by the blast of air. In winter it freezes the marrow in your bones, and in summer, when the air is red-hot, it desiccates the body.” The blast of wind also shook the theodolite making accurate measurements were very difficult. The preliminary survey determined the possible routes, maximum gradients, tunnel zones and sites for reversing stations. It was sufficient for making a rough cost estimate and for the authorities in Simla to give their approval. It was the stranded practice that had been applied to the Burma-Assam frontier railways and the Balochistan military lines. Detailed surveys of each section were conducted when the work was to be undertaken and the alignment adjusted in real-time especially for the tunnels.

Victor initially carried a revolver his escort of Levies was supplemented by a larger escort of rough looking Pathans detailed by the Malik/contractor whose area he was in. A Zakka Khel who had served in the Indian Army befriend him and gave him sound advice. “I notice Sahib that you always carry a revolver. There were many bad characters who could kill you from a distance with a rifle and it would be for the very revolver you carry that you would be killed. I suggest you give up carrying one.” Victor took it as sound advice and stopped carrying it for all the years he was supervising the construction.

Victor could not wait for Hearn to return from UK to start the actual construction phase of the Khyber Railway. His orders were to ‘get on with the job’ and he was confident that Hearn would approve. “Engineering is just organised common sense with no mystery or marvel behind it,” wrote Victor Bayley in his book ‘Permanent Way through the Khyber.’ New roads were constructed to take materials as close as possible to the construction sites but from there onwards it was the task of the beast of burden of the Frontier—the little but hardy donkey. They were indispensable in moving mountains of soil away from the cuttings and to make embankments for the line. Through the day they trotted back and forth and though the load they carried in gunny bags slung on either side was small, the aggregate load of the herd controlled by 1-2 men was large. As news spread that donkeys were in demand, “………. more and more of the little beasts appeared until there were thousands pattering about the work on their little hooves.”

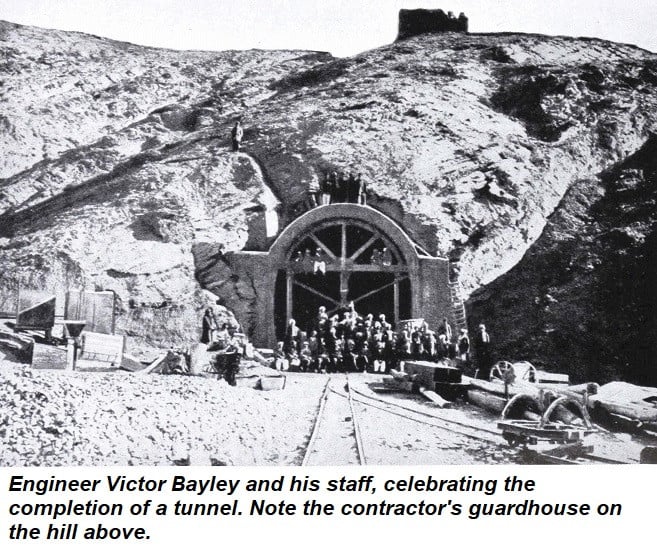

Hearn returned from Great Britian and the equipment started arriving to begin work on the tunnels. A large number of drills powered by petrol-driven air-compressors started hammering into the mountains and tunnels were worked from both ends. There was a total of 34 tunnels with a collective length of two and a half miles. The longest, tunnel number 20 located between the reversing stations of Zintara and Torra Tigga, stretched over a quarter of a mile and took nearly two years to complete. Nearly all the tunnels were on sharp curves and it needed very careful surveys to ensure that the two ends met.

None of the three mountain railways in India that preceded the KPR encountered a combination of hostile conditions, extreme weather, steep gradients and unstable geology that featured in the Khyber Pass. The Kalka-Simla Line had three times the number of tunnels but they were bored through stable rock. So too were the few tunnels of the Nilgri Line and the Darjeeling-Himalaya Railway had no tunnels at all. The soil strata in the Khyber were composed of brittle rock and shale that was compacted on the side and relatively easy to make a heading for a tunnel. However, in some cases, particularly in the Michni tunnel which was 400 yards long and others at the far end of the Pass, after a few yards of encountering ordinary shale, the drills sank in to a wet mush which further in became a stream of muddy water. In these tunnels, “… excavators, carpenters and masons worked under an incessant rain of mud and water as the timbers shoring the heading groaned under the pressure of an unstable mountain.”

Where the strata were very compact, gelignite was used to break up the mass for the drills to penetrate. The tribesmen became very adept at using explosives but Victor was terrified by ‘……. their total disregard of elementary precautions’. The detonator was inside a copper tube that was inserted into a hole in the gelignite stick and a pincer was used to crimp the open end of the copper tube after one end of the cord-like fuse had been inserted. If a pincer was mislaid, the tribesmen put the very sensitive detonator in his mouth and bit it. They were very fatalistic and indifferent to the injuries or deaths when they occurred. The Political Agent was very concerned about the large stores of explosives and some of it was pilfered but it did not bother Victor. He knew that it would be used in feuds which were a part of the culture of the tribesmen, and not against the military.

The KPR had a relatively modest overall climb but in some portions it had exceptionally steep ruling gradients of up to 1:25. These were beyond the power and adhesion of locomotives in a continuous climb. Tight ravines and spurs left no room for long loops and the solution was reversing stations because the train first ran forward into a dead-end siding, the points were changed, and the train reversed direction up the next section of track. By repeating this process, the line to gain height in short, manageable climbs rather than one impossible gradient. The KPR had four reversing stations between Jamrud and Landi Kotal, including the complex Tora Tigga section that led to Land Khana.

Though far from his wife and daughter in Peshawar, by living in Landikotal, Victor was close to the construction sites and it enabled him to become familiar with the tribes. The tents that had been erected in Landi Kotal for Victor and his staff were replaced by hutted accommodation and a small garden wih flowers and fruit trees gave a touch of civilisation. At night the sky was ablaze with brilliant stars and the stillness was immensely soothing till it was broken by the unpleasant crack of a sniper’s rifle followed a few seconds later by a nasty metallic clang as it hit a telegraph pole or a steel water tank. Very lights would light the sky, a machine gun would stutter and somewhere in the dark night would be heard a fusillade of rifle fire as a patrol of levies ferreted out the sniper. Such were the nights on a Frontier station but Victor couldn’t get used to it.

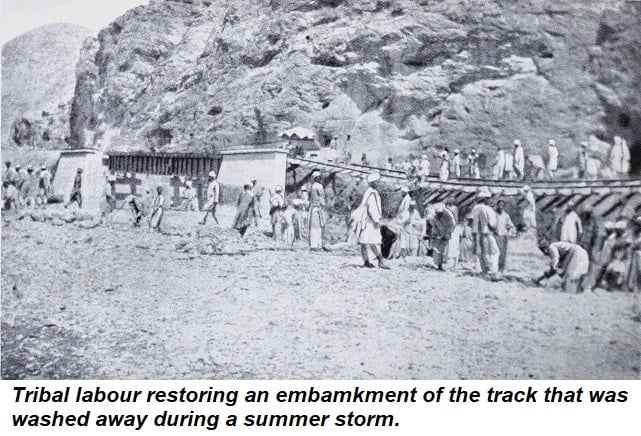

The temperatures in winters and summers were extreme. Landi Kotal was at a height of only 3,000 feet above sea level but it received snow in winters when the Westerlies brought moisture form the Mediterranean and Cawsapean Seas over the Afghan Plateau. In summers the monsoon could not reach this far west but storms with strong winds and downpours did occur periodically. They were localised and neither did not do much damage to the line or disrupt the pace work. However, in the third year of construction, the Pass was hit by a mother of storms, the likes of which even the oldest in the tribes had not witnessed in their lifetime. They said that there had been such a storm when Cavagnari and his escort of the Guides, was murdered in Kabul. However, next morning Victor was relieved to see that the damage was minimal because the line avoided large nallahs by moving well above them and boring through tunnels where there was the risk of landslides.

Through the five years of construction, protecting men and material remained a constant problem. Contractors were murdered because someone else wanted to grab the contract. Picquets were constructed and manned day the contractor to prevent sniping and occasionally became the scene of bloody fighting where adjoining contractors had a personal feud. Every evening the drills, pickaxes, shovel, crowbars were collected and guarded by the contractors’ own men. So also, were the stocks of material at sites for the bridges and tunnels. Ultimately, the task of protecting men and material became the responsibility of a 500 strong force of levies recruited from the local tribesmen and vouched for by their Maliks. The levies provided their own arms and ammunition and were paid by the Railways.

One of the major problems was to source materials. Timber required for shoring up the tunnel was available in large quantity in Nowshera to where Deodar was floated down the River Kabul. Coal was also transported from the mines in the Salt Range for the brick kilns established around Landi Kotal where there were deposits of brick clay. The bricks were required for lining the tunnels because the shale was useless and the limestone was so fissured that if crumpled. However, after being fired by coal, and mixed with fine brick dust the limestone was used for mortar in the time-tested manner. Cement was necessary for casting concrete and fortunately a British firm had established a cement factory near Wah. The sand was unavailable but the in the Khyber Nallah, there was pockets of natural gravel with fine particles deposits that was suitable for casting concrete.

As the sections of the line including bridges, culverts and tunnels were ready and connected to the line running up from Jamrud, a construction train started supplying heavy materials closer to the sites. The train was pulled by an old steam locomotive that performed admirably well. Ultimately it could be driven right till the outskirts of Landi Kotal. In a small ceremony Victor’s young daughter drove in the final pin and his wife drove the engine into the station constantly blowing the whistle. However, it took a few more months for the train to reach the end of the line at Landi Khana. But all was not well with Victor. The daily stress of supervising the KPR was starting to have a cumulative effect.

Dates were asked for the Viceroy, Lord Reading to open the line and opening ceremony was set for November 1925. Bayley coordinated planned and coordinated the entire event. However, the Lady Reading fell extremely sick and the Viceroy was represented by the Railway Member of the Governor General’s Council. A report in The Times of November 3, 1925, states that at the opening ceremony, the Chief Commissioner of the Indian Railway, praised, “... the marvellous achievement of the engineers, particularly Col Hearn and Mr. Victor Bayley. ... A special train took the guest up to Landi Kotal and the journey created unbound admiration.” Unfortunately, Victor Bayley was not present to receive the laurels. Six years of labour under daunting conditions had left him exhausted and he had departed for Great Britian with his wife and daughter who had faithfully remained in Peshawar all along.

When the line opened it was worked by HGS class 2-8-0 steam locomotives manufactured for the North Western Railway in the early 1920s by the North British Locomotive Company of Glasgow — the largest locomotive builder in the world. They were powerful enough to tackle the 1:25 gradient and the sharp curves. Yet even they struggled on the steep ascent which needed double-heading to haul loads. While descending, the brakes glowed red-hot, and drivers relied on sanders and skill to prevent runaway disasters.

After Independence, the KPR performed a more civilian role, carrying freight and tribesmen who paid no fare as they hopped on and off. Finally, it stopped running altogether, though it was revived briefly in the 1990s as the Khyber Steam Safari. The line has been abandoned after damage by floods and most of the brave HGS 2-8-0 have been scrapped. It is a pity that this part of our national heritage — what the newspapers heralded on its opening as “the most dramatic run in all India,” has been lost. Can we do something about it?

Syed Ali Hamid is a retired major general and military historian. He is also a heritage conservationist. He can be contacted at syedali4955@gmail.com.

All facts and information are the sole responsibility of the author