Pakistan has experienced rapid growth in internet access, smartphone usage, and engagement on digital platforms. While this expansion has created new opportunities for communication, employment, and civic participation, it has also been accompanied by a marked rise in online threats, harassment, and technology-facilitated offences. The increasing number of complaints submitted to national authorities reflects a growing public concern about safety in digital spaces, particularly for women and children. As online interactions become more deeply embedded in everyday life, the challenges associated with regulating, monitoring, and responding to digital harms have intensified, prompting national stakeholders to call for stronger protection mechanisms.

Federal Minister for Information Technology and Telecommunication Shaza Fatima Khawaja has emphasised that the Government of Pakistan is fully committed to ensuring that every woman and girl can participate in the digital world without fear.

Expressing deep concern over the rising risks women face online, she said, “Every day, we witness newer forms of digital abuse; deepfakes, hate speech and more recently sophisticated scams. There is growing evidence that digital violence affects more women than men. Therefore, I, as a woman, personally want to emphasise that digital violence against women must end,” she told The Express Tribune.

Federal Minister’s remarks came as the country joined the United Nation’s global campaign “16 Days of Activism 2025: End digital violence against all women and girls.

“Our message is clear: protecting women online is a national priority,” the Minister affirmed.

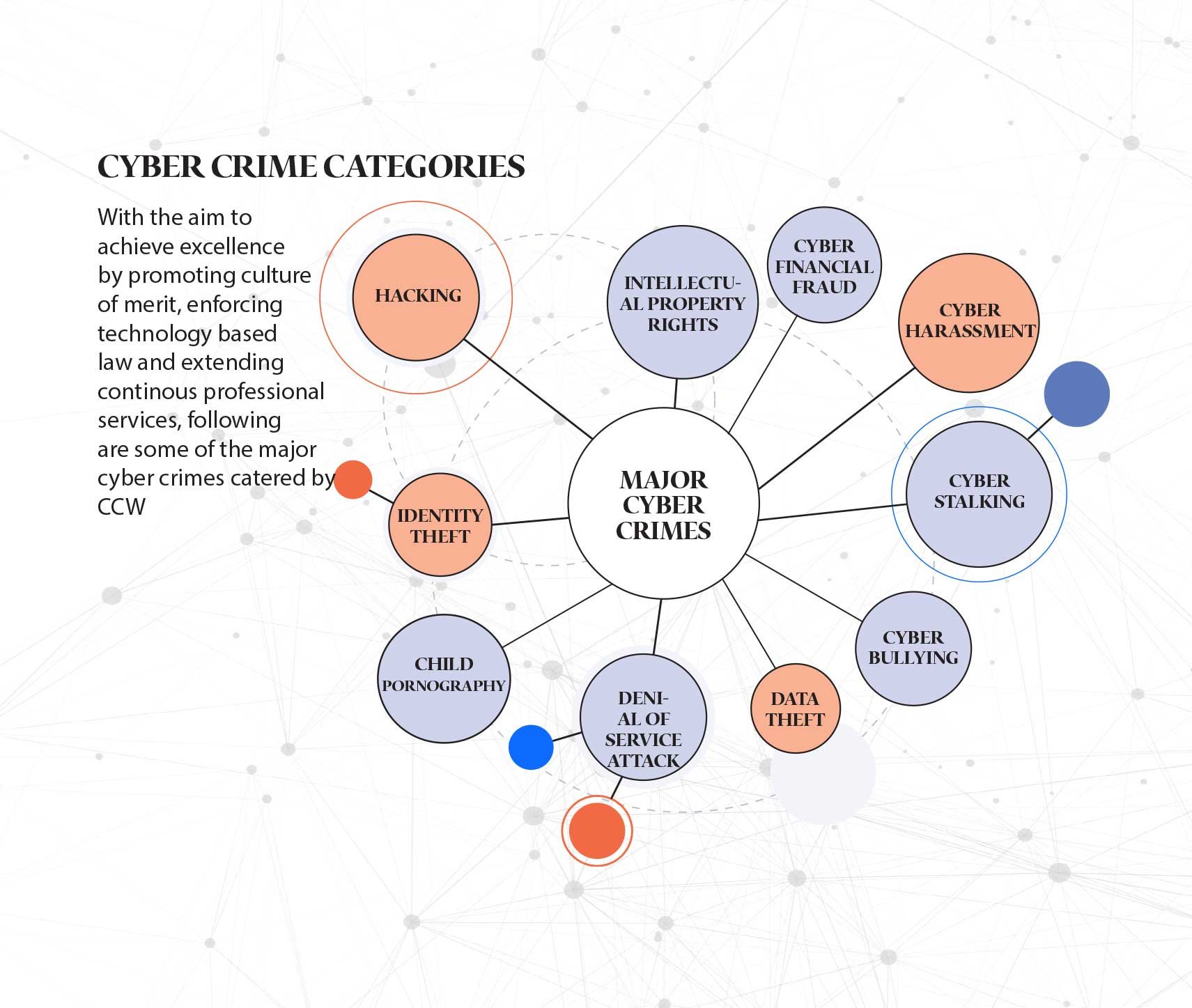

Khawaja highlighted that the government has taken active steps against cyberbullying and has strengthened digital reporting mechanisms. Pakistan’s Federal Investigation Agency cybercrime units are responding more effectively to complaints of harassment, stalking, impersonation, and image-based abuse.

She said digital violence can be extremely hard to stop and that requires a fully accountable and responsible government which ensures regulations are legally in place. To a question about the government’s measures she said, “We are aiming for a comprehensive approach by updating policies, improving platform accountability, supporting survivors through coordinated mechanisms, whilst investing in public awareness on digital safety.”

These efforts reflect the government’s broader vision of building a secure and rights-based digital ecosystem. Our nation cannot advance, technologically, socially, or economically, if even one woman’s voice is suppressed, added the Minister.

As the government is intensifying its efforts, she called for a meaningful change, which requires a collective shift in mindset and a refusal to tolerate violence in any form.

She also urged all segments of society to stand together against online crimes against women, girls and children, who deserve safe digital space to work and study only.

“I call upon every sector of society to unite with purpose. Our future depends on the courage we show today and together, we will shape a Pakistan where every woman can live, lead, and rise without fear,” Federal Minister emphasised.

Rising cyber threats

Pakistan is experiencing a dramatic rise in digital violence, a shift that mirrors the country’s increasing dependence on technology for communication, education, work, and social connection. As more women and girls navigate digital spaces, they are encountering new and complex threats that were unimaginable a decade ago. What once began as scattered incidents of online harassment has now evolved into a broad spectrum of digital harms that affect victims psychologically, socially, financially, and even physically.

While talking to the Express Tribune, Director General Science & Information Technology Department, Government of Sindh, Dr Rana Shahzad Qaiser commented that digital violence against women has evolved into one of the most alarming forms of modern gender-based abuse, driven largely by the rapid expansion of social media, increased smartphone use, and the anonymity offered by digital platforms.

Dr Qaiser, who is also the former digital forensics scientist at Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) Cybercrime Wing, now National Cyber Crime Investigation Agency (NCCIA) under federal government and an expert in cyberbullying and digital harms, also added “I observe that women—irrespective of age, profession, or socio-cultural background face a disproportionate share of online threats that aim to silence their voices, damage their dignity, and compromise their security.”

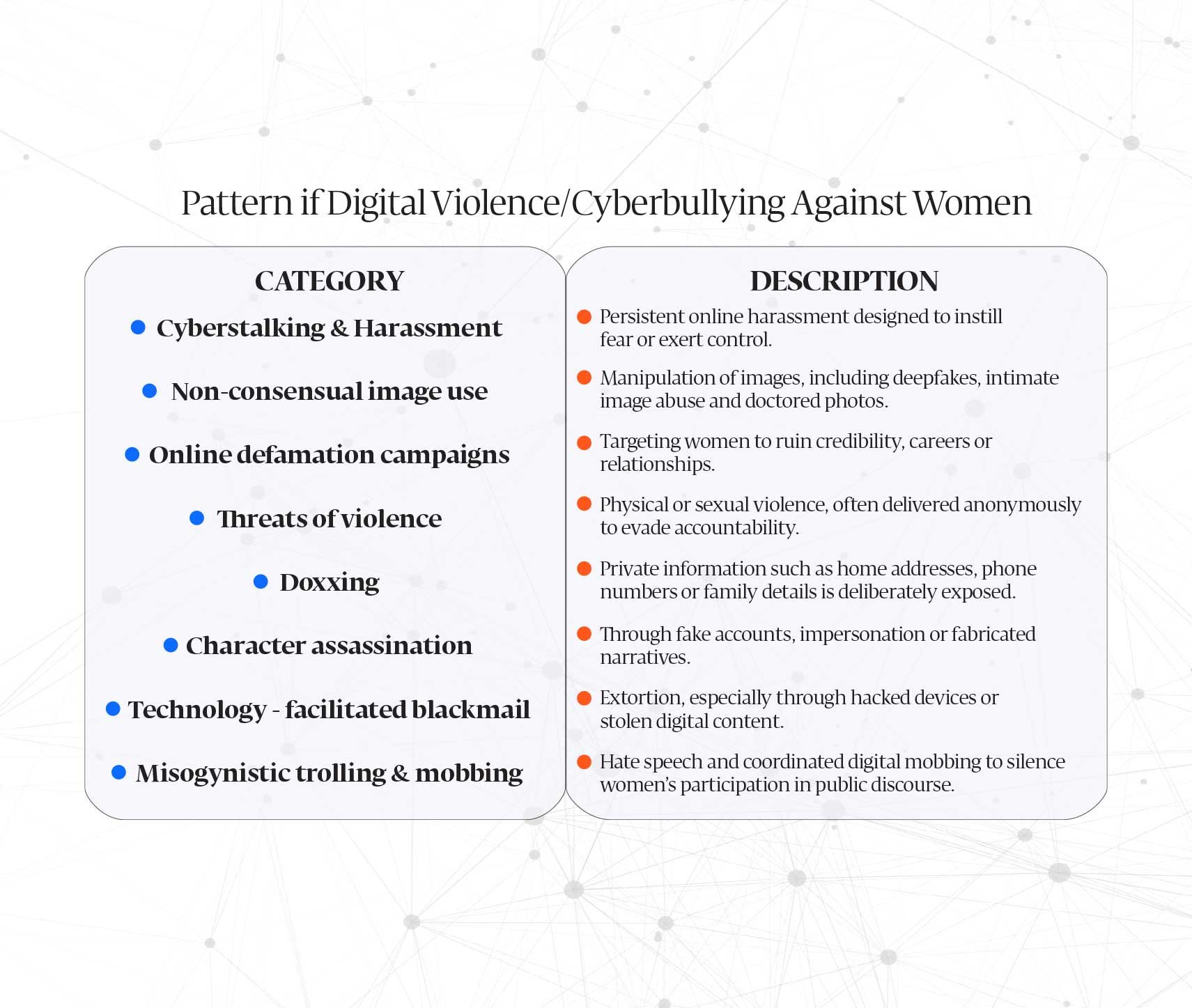

In my professional assessment, digital violence/ cyberbullying against women today spans a broad continuum of harmful behaviours, including but not limited to:

- Cyberstalking and persistent online harassment designed to instill fear or exert control.

- Non-consensual use or manipulation of images, including deepfakes, intimate image abuse, and doctored photos.

- Online defamation campaigns targeting women to ruin their credibility, careers, or relationships.

- Threats of physical or sexual violence, often delivered anonymously to evade accountability.

- Doxxing, where private information such as home addresses, phone numbers, or family details is deliberately exposed.

- Character assassination through fake accounts, impersonation, or fabricated narratives.

- Technology-facilitated blackmail or extortion, especially through hacked devices or stolen digital content.

- Misogynistic trolling, hate speech, and coordinated digital mobbing to silence women’s participation in public discourse.

These emerging patterns show that digital spaces have become extensions of offline power dynamics, where systemic gender inequalities are replicated—and in some cases, amplified—through technology.

He emphasised that cyber violence is not merely a "digital problem"; it has real psychological, social, and economic consequences, affecting women's mobility, professional advancement, mental health, and overall well-being. It undermines their right to express themselves freely and fully participate in digital ecosystems.

To counter this growing challenge, I advocate a three-pronged approach:

- Legal strengthening: Clearer laws, faster reporting mechanisms, cross-platform coordination, and better implementation of cybercrime statutes.

- Technological safeguards: Stronger privacy controls, advanced content moderation, AI-based detection of harmful content, and platform accountability.

- Awareness & capacity building: Digital literacy training for women, capacity-building of law enforcement, and nationwide public awareness campaigns on respectful digital behaviour.

Cyber bullying is preventable—but only through collective responsibility, where governments, platforms, educational institutions, and communities work together. My ongoing research and field experience strongly reaffirm that creating safer digital environments for women is not just a legal necessity; it is a moral and societal imperative.

A five-year assessment

According to official data available with The Express Tribune, , the nature of online abuse in Pakistan has become both more widespread and more technologically sophisticated, leaving victims to deal not only with the immediate danger but also the long-lasting trauma that accompanies these violations.

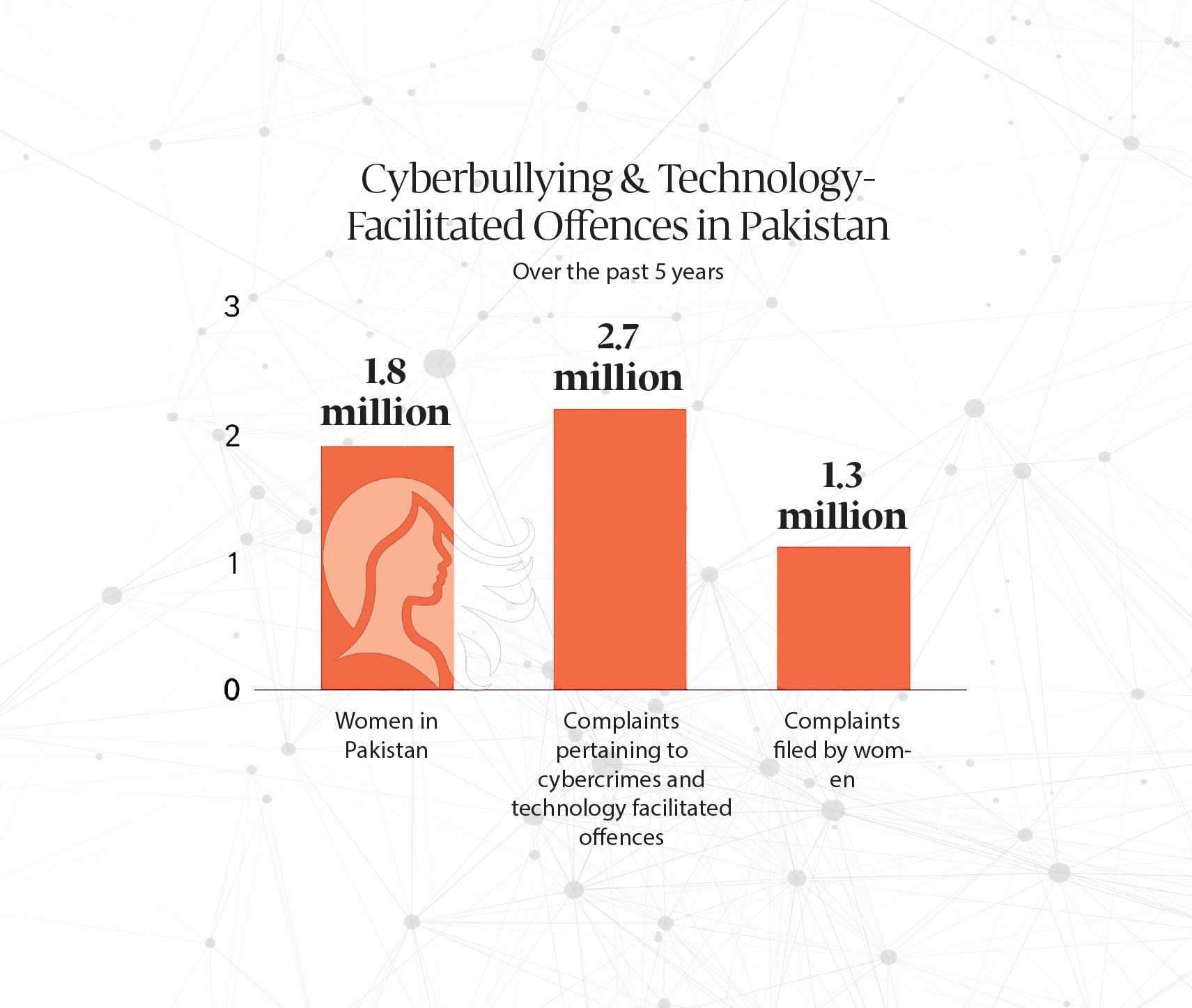

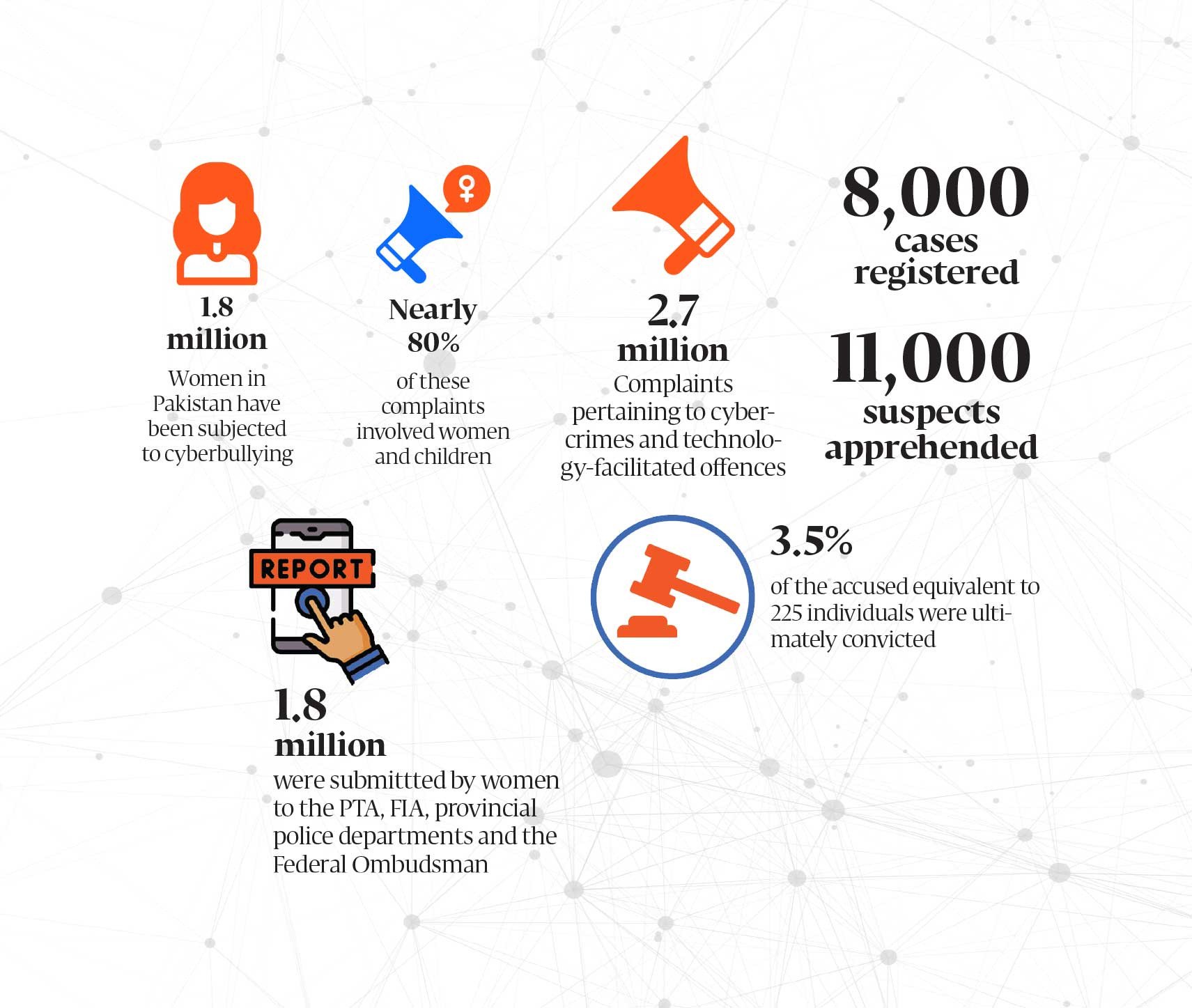

The data recorded over the past several years shows that 1.8 million women encountered cyberbullying or harassment during the period under review. This single figure represents a substantial portion of female internet users and illustrates the depth of exposure women face in online environments. It includes varied forms of abuse, from unsolicited contact and defamatory messaging to more severe forms of blackmail and image-based threats.

During the same timeframe, authorities across the country received 2.7 million cybercrime-related complaints. These ranged from financial scams and identity theft to hacking, cyberstalking, and extortion. The data shows that nearly 80% of these submissions involved women and children, positioning these groups as the most frequent targets within the spectrum of digital offences.

One of the visual summaries groups together the national total, the reported experiences of women, and the volume of complaints coming specifically from female users. This presentation makes clear that women constitute a significant share of the complainants. The number of submissions from women aligns closely with the scale of harassment they have faced, indicating that many victims chose to seek formal help rather than remain silent.

Information also traces what happened after complaints were submitted. Of the national total, 8,000 complaints became formally registered cases. Registration marks the point at which a submission qualifies under legal criteria for further investigation. The gap between overall complaints and registered cases suggests that many reports consisted of advisory queries, lacked sufficient evidence at the time of submission, or involved matters that did not meet thresholds defined under existing cybercrime laws.

Investigative activity led to 11,000 apprehensions, showing that authorities were able to identify and pursue alleged offenders in a portion of cases. Given the technical challenges of tracing digital footprints—particularly when anonymization tools, encrypted platforms, or international servers are involved—this number reflects situations in which digital evidence was accessible and actionable.

The judicial stage saw 225 convictions, a figure representing 3.5% of those accused. This outcome highlights structural difficulties: digital evidence must meet strict standards to be admissible, investigations often take significant time, and some complainants withdraw from proceedings due to social pressure or concern for privacy. The numerical progression—from complaints to registration, from registration to apprehension, and from apprehension to conviction—shows how the volume narrows at each stage of the system.

Together, the two visual summaries complement each other. One lays out the entire chain of information, from prevalence to justice outcomes. The other focuses on the relationship between the scale of women’s experiences, the national total of cybercrime activity, and women’s reporting behaviour. Using them side by side provides both a broad overview and a clear sense of proportionality within the data.

These national figures correspond with global assessments, including those referenced by United Nations bodies, which have observed a rise in technology-facilitated abuse as digital participation

designed to manage them, and improvements in reporting channels do not automatically lead to improved case resolution.

The dataset also carries social implications. The large number of women affected reflects the extent to which gendered forms of harm have migrated into online environments. The substantial share of national complaints that come from female users indicates that online abuse is not a marginal phenomenon but a routine and disruptive part of their digital experience. The strong representation of children in the overall complaint pool also points to risks for younger internet users, who may encounter grooming, manipulation, or exposure to harmful content without adequate safeguards.

From an institutional standpoint, the gap between complaints and registered cases points to the need for clearer classification systems, quicker evidence-preservation practices, and more support at the initial reporting stage. The difference between registered cases and apprehensions suggests that enhanced digital forensic capacity could broaden the range of cases that can be pursued. The limited number of convictions indicates the importance of strengthening legal processes, improving technical training, and ensuring coordination between investigative bodies and the courts.

The UN has emphasised that digital violence can have consequences comparable to offline forms of harm, affecting victims’ wellbeing, safety, and participation in public life. The Pakistani data reinforces these global findings, illustrating that online abuse can deter women from using digital platforms for education, employment, entrepreneurship, or civic engagement. International Finance Corporation (IFC) has also recommended that when women and girls are free from violence, economies grow stronger and opportunities expand for everyone.

While the data does not provide demographic breakdowns—such as age groups, urban vs rural distribution, or socioeconomic factors—it does indicate that digital violence is affecting women on a national scale. The high proportion of complaints involving children further suggests that young users lack adequate protection in digital environments and may face exploitation or harassment that goes unrecognized or unaddressed.

The comparison between the number of complaints submitted and the number of cases registered illustrates a need for clearer protocols on complaint classification, improved capacity for evidence verification, and stronger institutional coordination. Meanwhile, the gap between apprehensions and convictions highlights the importance of strengthening investigative procedures, improving digital forensics, and ensuring that legal frameworks are sufficiently comprehensive to address evolving forms of cybercrime.

Taken together, the five-year data shows a digital landscape in which online violations have increased rapidly, reporting has risen accordingly, but the system for resolving these complaints has not kept pace. The result is a high volume of cases entering the system, a small proportion progressing to formal investigation, and an even smaller number leading to convictions.

NCCIA Cybercrime Report – 2024 Overview

The National Cyber Crime Investigation Agency (NCCIA) reported notable developments in cybercrime trends for 2024. The agency recorded a total of 171,600 complaints this year, reflecting a 12.7% increase compared to the prior year. This rise underscores heightened awareness and an expanding culture of reporting cyber incidents nationwide.

Financial fraud continues to dominate as the most commonly reported cybercrime, accounting for 47% of all cases. This persistent trend highlights the urgent need for improved financial security measures and widespread public education.

Geographically, Lahore stands out as the leading district for reported cybercrime, representing 18% of the total complaints. This concentration may be attributed to factors such as higher population density, greater internet penetration, or more efficient reporting channels in the region.

Furthermore, complaints filed by females make up 21.6% of the reported cases, drawing attention to the critical necessity of addressing gender-specific cybercrime issues, including harassment and online abuse.

These statistics provide valuable insight for policymakers and law enforcement as they strategise to strengthen cybersecurity efforts and enhance victim support mechanisms in the coming year.

The human cost and trauma behind every case

Beyond the numbers and percentages lies the profound human cost of cybercrime. Each complaint represents an individual or a family affected—someone whose sense of security has been shattered, whose trust has been violated, and whose life may be forever altered. The rise in complaints, the predominance of financial fraud, and the alarming share of women reporting harassment or abuse all point to a stark reality: behind every statistic is a story of fear, loss, and resilience.

These figures are not just data points—they are reminders of the real people facing the consequences of digital crimes, often alone, seeking justice, protection, and peace of mind. Addressing cybercrime is therefore not only a matter of policy or enforcement; it is a moral imperative to restore safety, dignity, and trust to every affected individual.

Pakistan must do beyond symbolism

As Pakistan moves through another year of campaigns and awareness drives, there is a growing realisation that the United Nation’s “16 Days of Activism” should never be treated as a seasonal slogan or a decorative fashion event. Its purpose is far deeper than orange scarves, hashtags, or symbolic posts. The core of this global campaign is a call to actions that demand consistent work, structural reform, and long-term accountability.

Pakistan cannot afford to treat digital violence as a once-a-year talking point. The data shows that women, journalists, activists, trans individuals, and even minors are reaching out for help because the digital world around them is becoming increasingly unsafe. Their trauma is not temporary; it lingers long after campaigns end and social media timelines move on. The fear, shame, anxiety, sleepless nights, social isolation they endure is not eased by a slogan but by real protections and real change.

For the campaign to mean something in Pakistan, the country must invest in stronger reporting systems, greater digital literacy, widespread community support, and a social culture that refuses to blame victims. Schools must empower students with real tools to protect themselves online; families need to become safe havens that listen and support, not judge; law enforcement should be trained to combine technical skills with compassion; and society must rise together to challenge the harmful norms that let digital abuse flourish in the shadows. Change won’t happen through slogans—it will happen when every level of society takes responsibility and refuses to stay silent.

The true spirit of the 16 Days lies not in how loudly Pakistan talks about violence during this period, but in how committed it remains once the campaign ends. Progress will come from everyday efforts by listening to survivors, believing them, supporting them, and building systems that protect them before harm escalates.

If Pakistan chooses sustained action over seasonal symbolism, it can transform its digital spaces into environments where women and girls can speak, create, and live without fear. This campaign should translate into real policies and action, not just hashtags or photo-ops so that every woman and girl can be protected, heard, and empowered.

Taking steps beyond symbolism

As Pakistan moves through another year of campaigns and awareness drives, there is a growing realisation that the United Nation’s “16 Days of Activism” should never be treated as a seasonal slogan or a decorative fashion event. Its purpose is far deeper than orange scarves, hashtags, or symbolic posts. The core of this global campaign is a call to actions that demand consistent work, structural reform, and long-term accountability.

Digital platforms are frequently used as a new medium for existing societal patterns of harassment. “It is obviously a historical shift where different forms of abuse are finally being recognised as ‘violence,’" said Farhat Parveen, executive director of National Organisation for Working Communities.

Even women working for human rights—specifically on cases of domestic violence or harassment – face organised digital campaigns intended to silence them. This includes constant phone harassment and trolling across platforms like Facebook and WhatsApp.

Parveen highlighted the systemic challenges that persist: while victims can report incidents to cyber crime units, the existing infrastructure is weak and insufficient. She also emphasised that digital violence will continue until there is a robust system of accountability.

Pakistan cannot afford to treat digital violence as a once-a-year talking point. The data shows that women, journalists, activists, trans individuals, and even minors are reaching out for help because the digital world around them is becoming increasingly unsafe. Their trauma is not temporary; it lingers long after campaigns end and social media timelines move on. The fear, shame, anxiety, sleepless nights, social isolation they endure is not eased by a slogan but by real protections and real change.

For the campaign to mean something in Pakistan, the country must invest in stronger reporting systems, greater digital literacy, widespread community support, and a social culture that refuses to blame victims. Schools must empower students with real tools to protect themselves online; families need to become safe havens that listen and support, not judge; law enforcement should be trained to combine technical skills with compassion; and society must rise together to challenge the harmful norms that let digital abuse flourish in the shadows. Change won’t happen through slogans—it will happen when every level of society takes responsibility and refuses to stay silent.

The true spirit of the 16 days lies not in how loudly Pakistan talks about violence during this period, but in how committed it remains once the campaign ends. Progress will come from everyday efforts by listening to survivors, believing them, supporting them, and building systems that protect them before harm escalates.

If Pakistan chooses sustained action over seasonal symbolism, it can transform its digital spaces into environments where women and girls can speak, create, and live without fear. This campaign should translate into real policies and action, not just hashtags or photo-ops so that every woman and girl can be protected, heard, and empowered.