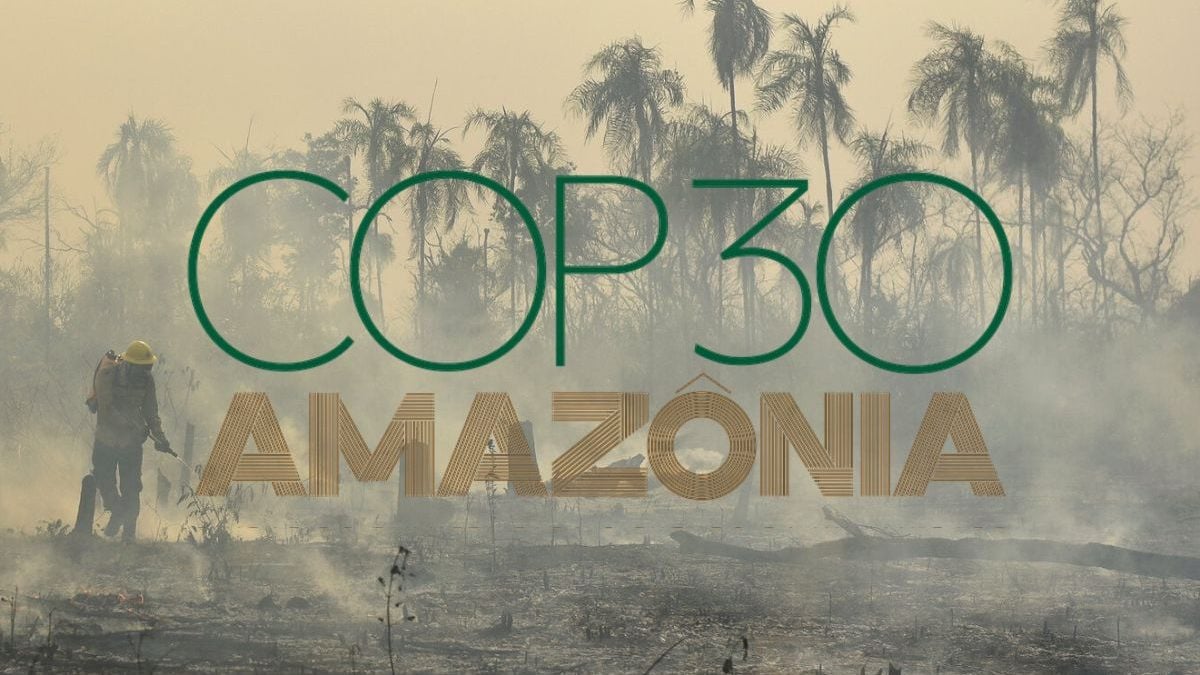

World leaders are gathering again this year, this time in Belém — a city at the mouth of the Amazon River — for the thirtieth United Nations Climate Change Conference, COP30. Brazil has promised an “Amazon COP,” a summit that would finally give the largest rainforest, and the communities who protect it, a seat at the table. But the table itself looks shakier than ever.

In the years since the Paris Agreement, the conferences have become rituals of hope and exhaustion, a choreography of urgency performed under the fluorescent lights of negotiating halls. But this time, the geopolitical stage is bleaker. Wars rage across three continents. The planet has just endured the hottest year in recorded history. And sitting once again in the White House is Donald Trump — the man who called wind turbines “ugly,” ridiculed climate science as a hoax, and re-centered American policy around oil, coal, and militarism.

But if COP30 was meant to re-anchor the world’s climate ambitions, Trump’s second term has ensured that the anchor will drag. UN Secretary-General António Guterres, according to a recent Reuters report, condemned nations for failing to limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. Leaders attending the summit lamented the fractured global consensus on climate action, taking pointed jabs at the climate-denying Trump administration while assuring the world that the mission to tackle the climate crisis remains alive.

Still, the climate agenda survives in name only, hanging by a thread between ambition and reality.

A summit overshadowed

In Belém, Brazil’s diplomats have promised that COP30 will restore faith in multilateral climate action. But many of the negotiators arriving for the conference know better. The past year’s sessions under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change were dominated by disputes over loss and damage financing, the slow pace of phasing out fossil fuels, and the widening chasm between rich and poor nations.

Patrick Bigger, research director at the Climate and Community Project, describes what an honest COP agenda should look like if stripped of the diplomatic theatre.

“It would be restricting the exploitation and burning of fossil fuels,” he said. “It would be about preventing the loss of tropical rainforests, about contending with the structure of the international financial architecture that makes it impossible for countries in the Global South to pay for adaptation.”

The COP process, he believes, has consistently avoided these fundamentals. “It would be about reparations for the Global South in the form of loss and damage… about the equitable sharing and technology transfer for renewable technologies,” he added. “It would be the basic tenets of climate justice.”

His frustration is widely shared. Behind the slogans of “keeping 1.5 alive,” diplomats now trade in diminished expectations. Even before Trump’s return, countries were missing their emissions targets – with him in office, the world’s largest historical emitter has only turned its back once again on decarbonisation.

The Trump effect

In Washington, the second Trump presidency has swung open the gates for fossil fuel expansion. He launched his term with the infamous “drill, baby, drill” line in his inauguration speech in the Capitol rotunda. Tax breaks for oil and gas have returned, while subsidies for offshore wind and solar — once pillars of the Inflation Reduction Act — are being clawed back. Federal agencies have been instructed to “streamline” drilling permits on federal lands, and banks are quietly nudged to loosen credit for extraction projects.

A recent Financial Times report described Trump “twisting the arms” of financial institutions to fund drilling and pipeline projects across Latin America and Africa. The global fallout, Bigger cautions, will be severe.

“That will take the form of increased extraction of fossil fuels,” he said. “It’s twisting the banks’ arms, but it’s also twisting the arms of other sovereign countries. If they want to remain in Washington’s good graces — by trade or by military protection — they’ll have to authorise new extraction and slow-walk the transition.”

Trump’s economic nationalism has also intensified the fracture between trade blocs. The US-led bloc, obsessed with data centres and re-militarisation, now competes with China’s industrial ecosystem of solar, battery, and electric-vehicle manufacturing. The result is a new Cold War that drains attention from planetary survival.

“It’s not just Trump’s rhetoric,” Bigger said. “The US trade bloc going all in on AI and militarism is the de facto industrial strategy. It’s incredibly resource-intensive, competing for inputs with renewables and with the socially useful stuff we need to deal with the climate crisis.”

Distractions of conflict

Even as the climate clock ticks down, the world’s headlines — and budgets — are consumed by war. In Gaza, entire neighbourhoods have been reduced to rubble; in Sudan, famine shadows the displaced, in Ukraine, the frontlines are frozen but the shelling hasn’t stopped.

“War industries, particularly in the US and Europe, are playing a huge role in the climate crisis,” Bigger said. “Think of NATO’s new spending rule — three to five percent of GDP. That means more emissions, more liquefied natural gas imports to power the new tank factories in Germany. The peace side of the conversation is still underappreciated.”

Every missile, every tank factory, every emergency airlift burns through the same carbon budget the planet cannot afford. According to conflict-tracking researchers, the war in Ukraine alone has emitted more carbon than several small nations combined. In Gaza, bombing has turned urban life into dust and chemicals — a toxic wasteland that will poison groundwater for generations.

“Weapons that get built tend to get used,” Bigger said. “More weapons don’t make us safer. They make the world more dangerous — and they shrink the space we have to find common ground on climate.”

A paralysed multilateralism

At last year’s COP in Baku, lobbyists from the oil and gas sector outnumbered the delegates of most low-income nations. This year, Brazil hopes to stage a moral contrast. But the contradictions remain: major petro-states, from Saudi Arabia to the US, still dictate the terms.

“It makes no sense for petro-states to host this thing,” Bigger said. “It makes no sense for oil companies to be allowed armies of lobbyists. But nonetheless, we need that kind of space. If we didn’t have COP, we’d have to recreate it.”

His analogy is striking. He compares COP to USAID after the budget cuts – deeply flawed, sometimes complicit in harm, yet still indispensable. Without it, there would be no forum left — however imperfect — for confronting the planetary emergency.

But the contradictions are deepening. Trump’s return has emboldened oil producers in the Gulf and beyond. He counts among his allies the very leaders whose economies depend on fossil fuel exports. His recent visit to the region reportedly ended with private jets gifted by Qatari businessmen — a metaphor for the new political economy of indulgence.

“I’m afraid the answer is: as much as they want to,” Bigger said when asked how far petro-states might go. “It’s hard to see Trump restraining Saudi Arabia if it wants to resume large-scale slaughter in Yemen, or any of these countries engaging in military adventurism. The administration will only support them through arms sales and intelligence sharing.”

Europe falters, China surges

Once seen as a moral anchor of the climate agenda, Europe now looks directionless. Some governments have retreated from net-zero timelines amid rising energy prices and far-right populism. Others have folded under US pressure to buy liquefied natural gas.

“Europe on the whole does not feel like where the world should be looking for answers,” Bigger said. “If anybody was going to drive a rapid transition, Europe would have already done it. Instead, we have to look at the new formations being created around China.”

Indeed, while Western politics slides toward paralysis, China’s renewable capacity has exploded. Its emissions appear to have peaked ahead of schedule; its dominance in solar, battery, and EV supply chains is reshaping the global energy map.

“The fact that Chinese emissions have almost certainly peaked is an astonishing achievement,” Bigger noted. “They’re becoming an energy superpower on par with the US or Saudi Arabia — but for renewables.”

At the UN this year, Beijing pledged to cut emissions by seven to ten percent — a move that, if delivered, could offset some of the damage from Washington’s backslide.

“They’re putting their money where their mouth is,” Bigger said. “Much more than, say, Obama ever did.”

Wars that erode the future

The wars themselves are not just distractions – they are accelerants of ecological collapse. The environmental destruction in Gaza, Sudan, and Ukraine underscores a truth the climate community rarely says aloud: war is incompatible with planetary survival.

“There's an increasing appetite to talk about this,” Bigger said of the upcoming COP agenda. “It’s encouraging that Brazil — a leading force in condemning the genocide in Gaza — is hosting. But let’s be honest: if countries can’t even agree to stop burning fossil fuels, it’s implausible that COP can be a space to deal with acute military crises.”

At best, he expects “a voluntary report” acknowledging the emissions of war. “Israel isn’t going to sign up to that. The US isn’t. Russia isn’t,” he said.

This grim realism reflects a deeper weariness within the climate community. For every new summit, there are more promises, more press releases, and more jet fuel burned to get there. The symbolism of thousands of delegates flying to debate emissions reductions has become a cruel joke.

The fossil grip

When Bigger speaks of reform, he sounds both cynical and determined. “You have to be able to restrict the credentials of people who are there solely to impede progress,” he said. “There have to be mechanisms for that.”

“It’s the same problem we have in US politics,” he said. “Corporate money is effectively unimpeded in influencing politicians. Similarly, the oil industry runs riot across these dialogues.”

This revolving door between politics and petro-capitalism has turned the COP process into something resembling an annual shareholders’ meeting of the carbon economy. The last summit’s official sponsors included several oil majors and airline alliances. The irony isn’t lost on activists — nor on Bigger.

The militarised economy

Bigger’s broader critique cuts deeper than diplomacy. He argues that the entire economic model of the transatlantic alliance — centred on arms manufacturing and fossil energy — is incompatible with the climate transition.

“It’s difficult to disentangle national interests and the interests of major arms companies,” he said. “Within the logic of economic growth, it’s hard to see how many countries have an appetite to rein any of that in.”

The numbers bear him out. The US and Europe together account for more than three-quarters of global arms exports. Defence spending now competes directly with climate finance; in 2024, NATO members collectively spent nearly 1.5 trillion dollars on the military — fifteen times what wealthy nations delivered for climate adaptation in poorer countries.

Glimmer of hope

And even in this bleak landscape, there are shards of progress. Bigger points to China’s over-supply of solar panels — “there’s no such thing as too many cheap solar panels right now” — and to pockets of grassroots climate policy in the United States.

“The state of Illinois has passed a very good new climate law,” he said. “It’s focused on bringing workers and communities along — a just-transition model. In New York, the Build Public Renewables Act is creating publicly owned energy systems. There is good stuff happening, and I don’t want to underplay that.”

In Europe, too, a younger generation of politicians is stirring. Britain’s Green Party has become a force in local politics; Spain has defied NATO’s call for higher defence spending, citing emissions concerns. These are small ripples, but ripples nonetheless.

The long emergency

If there is one consensus emerging from scientists and activists alike, it is that time is running out for half-measures. The global temperature rise is edging toward 1.5 °C — the threshold set in Paris that was supposed to represent the upper limit of safety. Crossing it risks triggering irreversible changes: ice-sheet collapse, ocean acidification, mass displacement.

The world’s ability to respond now depends on whether multilateralism can be salvaged from its own fatigue. For Bigger, that means not abandoning COP, but rebuilding it. “Multilateral spaces for dialogue are incredibly important,” he said. “They’re more necessary now than ever. COP is clearly not fit for purpose, but we still need it.”

The alternative — a fragmented world where each bloc pursues its own survival — would be worse.

The Amazon as mirror

Hosting COP30 in Belém was meant to signal renewal. The Amazon, after all, is both a carbon sink and a warning — a system tipping toward collapse under the weight of deforestation and drought. President Lula has pledged to end illegal logging and position Brazil as a global climate leader. But even here, the contradictions are blatant – agribusiness remains politically untouchable, and mining continues to encroach on Indigenous lands.

Experts warn that if the Amazon teeters despite global attention, the prospects for the rest of the planet look grim.

The question that remains

When asked if he sees any reason for optimism, Bigger pauses. “No,” he admits, “not really.” And then, after a moment – “If you’re looking for climate success stories, you really have to go to the emergent Chinese-led trade bloc. But in the aggregate, the direction of travel — this ‘all-of-the-above’ energy policy — is suicidal.”

The world faces a deliberate, self-inflicted erosion of the conditions that make life possible. Wars, pipelines, arms races — each an act of denial masquerading as pragmatism.

When delegates arrive in Belém, they will be surrounded by the lush, humid vastness of the rainforest — a reminder of what still lives and what could be lost. COP30, experts believe, was meant to mark the world’s recommitment to survival. Instead, it may serve as a mirror -- a reflection of a civilization unable to change course even as the fire reaches its doorstep.