While poverty is often seen as the primary predictor of malnourishment, it fails to account for the gender-specific disparities in access to nutrition that have steadily led to the development of chronic nutritional deficiencies among women and girls in the country.

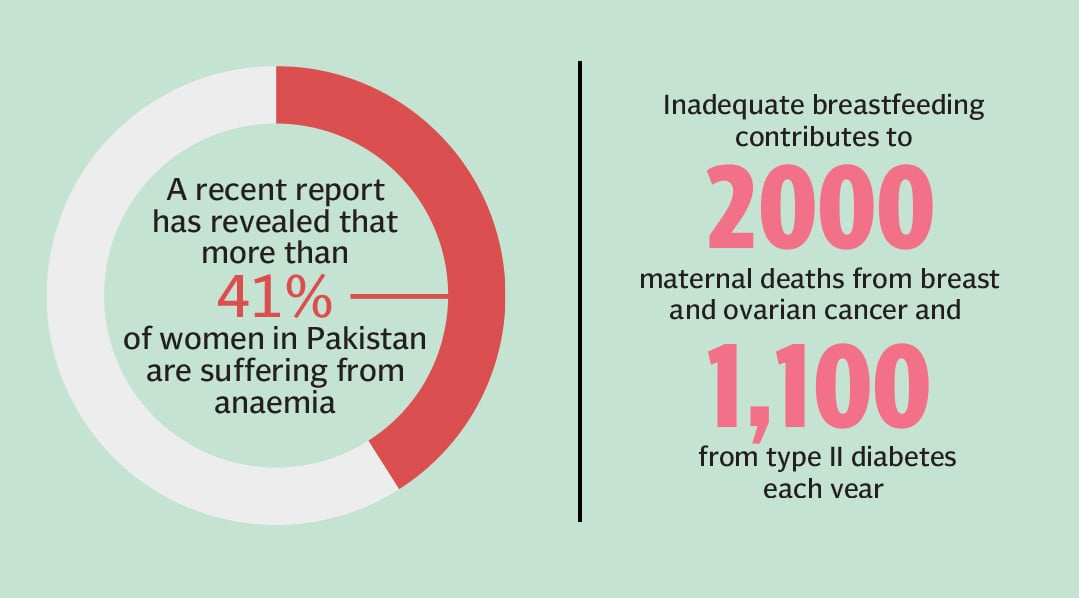

According to Dr Basmaa Ali, Clinical Instructor in Internal Medicine at the Harvard Medical School, malnourishment, particularly iron-deficiency anaemia is a huge problem in Pakistan since it causes the national IQ score among girls to drop by three to five points, which is 5 per cent of our GDP.

“Growing up if you have anaemia, your brain does not develop since haemoglobin is needed to supply oxygen. Hence, the affected women and girls are unable to develop the intellectual prowess needed to excel in the public sphere,” revealed Dr Ali.

On the other hand, Dr Nighat Khan, General Secretary at the Women Care Foundation of Pakistan highlighted the fact that nutritional deficiencies not only impacted the development of female adolescents but also had dire consequences for their future children.

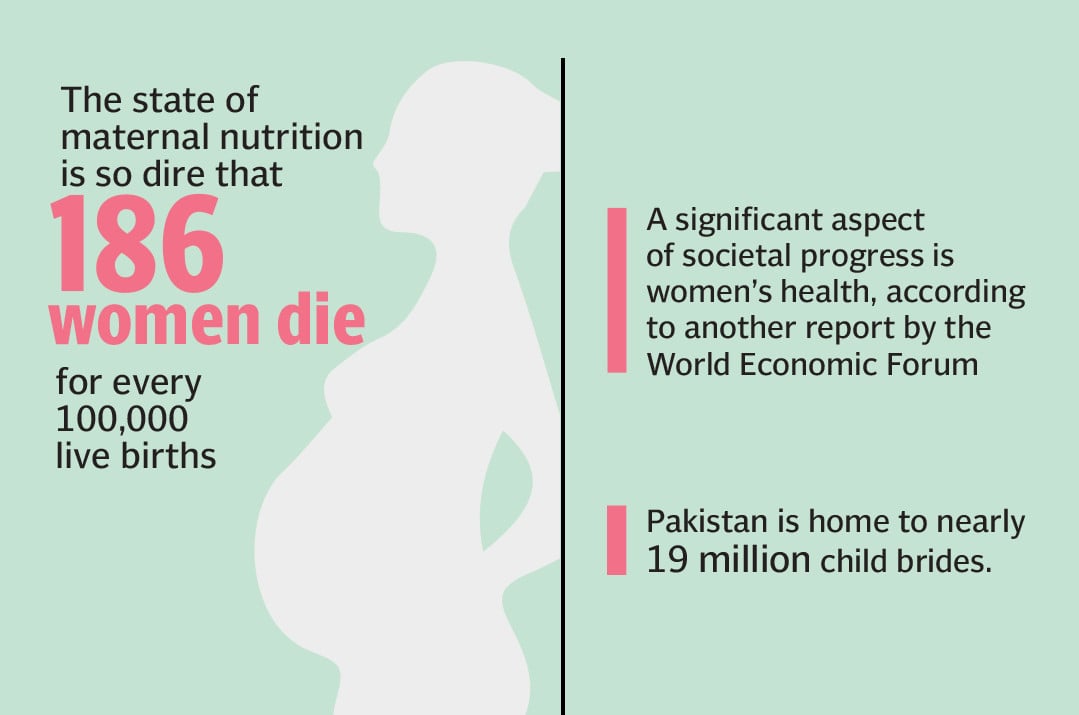

“Girls who suffer from severe malnutrition face various medical complications during pregnancy. Even when they give birth successfully, the child born is underweight and is susceptible to acquiring various diseases,” claimed Dr Khan.

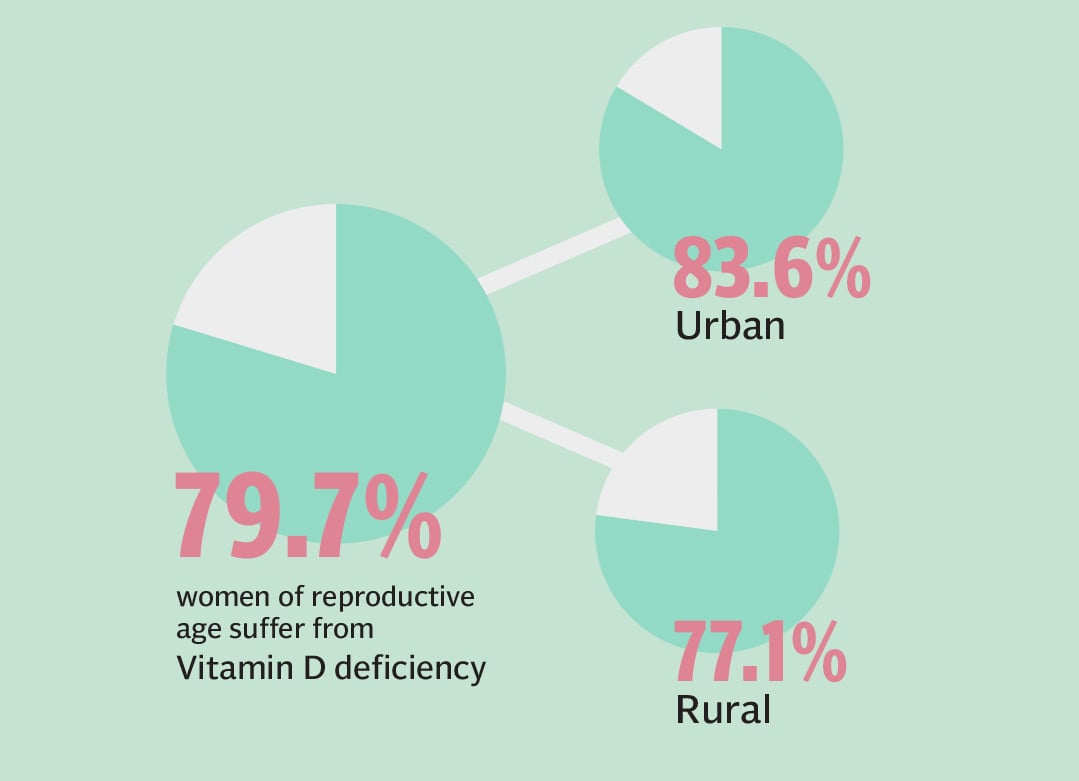

“Approximately 50 per cent of women in urban areas and 75 per cent of women in rural areas are suffering from some nutritional deficiency especially of iron and calcium,” explained Professor Dr Jahan Ara Hassan, Professor of Gynaecology at the Dow University of Health Sciences.

Whilst acknowledging the hazards of malnourishment, Dr Ali felt that genotypic variations among different populations could partially explain the staggering figures highlighting anaemia in Pakistan.

“We rely on Western medical guidelines, which label women with a haemoglobin level of 11g/dL as anaemic, even though these levels are perhaps normal in our local female population. The average haemoglobin levels among women in our country are genetically lower,” noted Dr Ali.

While it could be said that the figures on malnourishment might be exaggerated, the interplay of various gendered social factors hindering access to nutrition for women and girls perpetuates a vicious cycle of malnourishment, which hampers the quality of life of females across socio-economic backgrounds.

Taste of discrimination

In a male-dominated society where women are stereotypically relegated a lower status, gender discrimination is a harsh reality withholding half the population from equally accessing education, healthcare, employment and even nutrition.

Since sex determination through a sonography is allowed in Pakistan, gender discrimination in nutrition often begins even before a girl child is born. Families that have knowledge of the gender of the child convey their bias through the quality of care given to the expectant mother.

Nazia*, a 21-year-old first time mother was over the moon when she was told by her doctor that she was carrying a boy. However, her days of happiness were short-lived since a couple of months later she delivered a baby girl.

“Although my husband was happy, my mother-in-law was distraught since she worried for her poor son who now had the burden of a daughter on his shoulders. To express her resentment, she did not even announce the birth of my daughter in the family,” recalled Nazia.

Nazia’s heart-breaking experiences were corroborated by healthcare providers during a study undertaken by the Population Council to study son preference in Karachi. According to the respondents, pregnant women carrying male children reported being treated better by their families, who would take special care of their nutrition and rest.

In Nazia’s case, her mother-in-law, who would feed her nuts and milk during pregnancy, stopped caring for her nutritional needs after the birth of her daughter. “Whenever I would nurse my daughter, she would order me to do some household chore. I was forced to stop breastfeeding my daughter so that I could conceive a boy soon after. This treatment continued until I had my son two years later,” recalled Nazia, whose daughter suffers from stunting.

Published by the Quarterly Journal of Economics, a study exploring breastfeeding practices in India revealed that a negative covariance was found between the duration of breastfeeding and parents’ plans for subsequent births. Since breastfeeding physiologically lowered a woman’s fertility, after the birth of a girl, parents were more likely to limit breastfeeding in order to try for a boy.

Regrettably, such discriminatory practices only worsen as the girl grows older. Dr Basmaa Ali, Resident Scientist at the Lahore University of Management Science (LUMS) informed that in many areas across the country, iron-rich foods were still considered premium foods reserved for boys.

“Eggs, chicken and red meat are first given to boys and then to girls hence the latter have no iron supplementation. Plant-based iron must be consumed in large amounts for efficacy. Three cups of cooked spinach are required most days of the week to fulfil the body’s iron requirement. However, a lot of times this is not feasible,” claimed Dr Ali.

“One in seven women in Pakistan is undernourished, while nearly half of the female population suffers from iron deficiency anaemia, which is a major factor contributing to miscarriages among pregnant women. Furthermore, the deficiency of vitamins A and D is also quite common among women and adolescent girls in the region,” noted Dr Bushra Khalil, Head of Nutrition at the Lady Reading Hospital in Peshawar.

Starved by standards

Upon reaching puberty, the nutritional requirements of female adolescents increase sharply to compensate for the monthly loss of blood. Unfortunately, however, this is the exact same time when societal pressure to fit the conventional standards of beauty encourages young women to zip their mouths shut.

Alina*, a 16-year-old student struggled with obesity since childhood. However, the unease that she felt within her own body hit a whole new level once she entered her teenage years. While her favourite online influencers could pull off any outfit grabbed at the mall, she had to spend hours finding the correct fit. Tired of the constant body shaming and desperate to lose the extra pounds, she decided to turn to YouTube for help.

“I came across this juice detox diet, which guaranteed significant weight loss within two weeks. All I had to do was only drink juice the whole day. What could possibly go wrong?” shrugged Alina, who whilst suffering from heavy menstrual bleeding was unaware of the repercussions of her highly restrictive diet.

Soon after, Alina started fainting in school on a daily basis and eventually required multiple blood transfusions to correct her severe anaemia. “I wish society was not as unforgiving for young girls. Children should never be body shamed since adolescence is a time when their bodies are still developing. Unfortunately, our constant exposure to the perfect physiques of influencers only further ruins our self-esteem,” said Alina, who has consistently struggled with anorexia.

According to the Cureus Journal of Medical Science, adolescent’s exposure to ideal body types on social media has significantly increased their susceptibility to following fad diets and developing eating disorders over the past few years.

Explaining Alina’s case, Dr Ali revealed that in girls, iron was not stored as fastidiously as in boys hence it must be restored through food. “Heavy menstruation is quite common, especially during the initial few years of menarche. When this blood loss is not corrected through food it leads to anaemia,” highlighted Dr Ali.

In order to correct anaemia, it must first be diagnosed. In Pakistan however, taboos surrounding menstruation prevent young girls from discussing issues like heavy bleeding with female caregivers while the stigma associated with taking an unmarried girl to a gynaecologist prevents many mothers from seriously addressing their daughters’ concerns.

“Women’s reproductive health, including menstruation, is all taboo in our country. When I was a medical student in Pakistan, every time we would take the menstrual history of a female patient, the male professor would have a sly smile on his face while all the male students at the back would invariably smirk. Later, when I went to the US for my residency, I was presenting a woman’s medical history to my male supervisor in a class of nearly all male students and not a single one of them acted weird,” recalled Dr Ali.

Dr Ali further opined that in order to destigmatize women’s reproductive health, it was necessary to raise awareness about the topic in the local languages. “The reproductive system is just like any other part of the body. Talking about this subject in English allows us to distance ourselves from it. Therefore, we should talk about it in Urdu and the other vernacular languages to reduce the stigma. That’s the only way to make it normal because as long as it is considered a matter of shame, people will not talk about it,” noted Dr Ali.

Hunger for heir

“It’s a girl.” Till date, the following revelation is received by families in two extreme ways. An open exhibition of outright shock or a well mastered display of feigned exuberance. In both the scenarios, the new parents are tacitly consoled by the clichéd declaration that daughters are a blessing from God and that having a healthy baby is all that matters. However, in discreet words the mother is told that her nine-month long journey of patience was fruitless since it ended with the disappointing birth of a sour fruit.

Not much different was the plight of Hajra Bibi, a 25-year-old mother hailing from the Momand Agency, whose failure to produce a son landed her in an endless cycle of consecutive pregnancies. “The doctors advised me against conceiving another child because of my severe anaemia. I tried explaining this to my husband but he insisted on having a son despite my health struggles,” bemoaned Hajra, who is pregnant once again.

Hajra’s case is a classic example of son-biased fertility stopping behaviour, under which the desire to have one son or a desired number of sons leads couples to continue having more and more daughters, significantly deteriorating the mother’s health.

Dr Muhammad Rizwan Safdar, Assistant Professor of Sociology at the Institute of Social and Cultural Studies (ISCS), University of Punjab highlighted the fact that the prevailing cultural mind-set in the country actively encouraged couples to continue having children until a son was born. “Son-biased fertility stopping behaviour often leads to malnutrition in mothers,” said Dr Safdar.

However, the gendered consequences of son-biased fertility stopping behaviour extend beyond the health of the mother, entailing much deeper repercussions for the ill-fated cohort of girls, who are seen as little more than the pitiful outcomes of repeated failed attempts at having a boy. Given the limited economic means of the average household, the nutrition, education and life outcomes of these girls are all significantly impacted, with their futures obscured by the darkness of both malnutrition and child marriage.

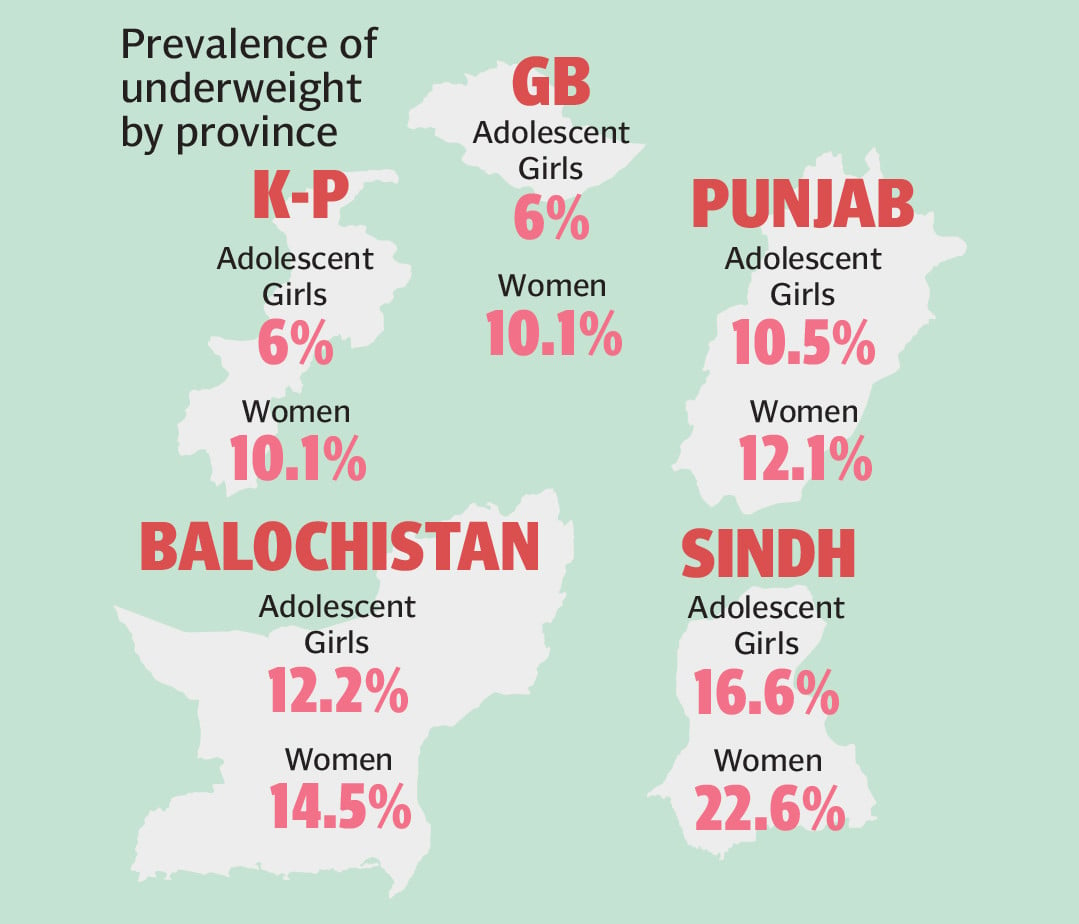

According to the National Nutrition Survey 2018, over half of adolescent girls in Pakistan suffer from anaemia, with rural areas hit the hardest. While the prevalence of anaemia among girls in urban areas stands at 54.2 per cent, a staggering 58.1 per cent of adolescents hailing from poverty-ridden areas are affected.

Research by the Future Business Journal confirmed that children with a large number of siblings were more likely to suffer from malnutrition while a study published by BMC Women’s Health revealed that girl’s belonging to large families with more than five members were at an increased risk of child marriage. Therefore, it is seen that son-biased fertility stopping behaviour leads to the birth of more girls than the family can afford to feed therefore, the easiest way out of a financial crisis is to lend their frail hands in marriage.

Moreover, the results of a study exploring the link between female early marriage and son preference in Pakistan published by the Journal of Development Studies concluded that girls who were married before the age of 18 not only expressed a greater desire for having male children but were also less likely to stop reproduction until or unless they gave birth to a boy. Hence, the cycle of son preference and malnutrition survives through generations, silently bedeviling the health of millions of women and girls in the country.

Breaking the cycle

Whether women want to improve bone strength to manage daily tasks or flaunt flawless skin, hair and nails at a wedding, the billion-rupee vitamin and minerals market claims to offer a myriad of benefits. Beguiled by the tactful marketing strategies, very few consumers stop to ponder how effective these supplements really are?

“From an evolutionary standpoint, our food is much older than humanity, which has actually co-evolved with its food. The body recognizes nutrients in the matrix of food. Therefore, when you take calcium or iron in a pill form, the body is unable to recognize them as nutrients. For iron the studies are not as good, but for calcium we know that 10 times more calcium is absorbed through food than from tablet form,” emphasized Dr Ali, whose medical practice integrates the principles of Ayurveda with those of western medicine.

Hence, Dr Ali stressed the importance of supplementation through food. “In order to prevent and correct anaemia, women and girls should eat red meat, liver, and eggs regularly alongside incorporating a good number of green vegetables especially spinach, into their diet. Iron-rich foods should be taken alongside foods that are high in vitamin C since the micronutrient is needed for iron’s absorption,” explained Dr Ali.

Since female adolescents spend a large part of their day at school or college, Dr Ali believed that educational institutions could play a part in improving nutritional outcomes among women. “Unfortunately, however, high carb junk foods dominate the menu at nearly all educational institutions. On the contrary, in countries like Japan, a nutrition profile is made for foods to highlight the exact quantity of protein, carbs and fresh vegetables necessary for students across all ages. Nutritious foods, however, require proper storage. Therefore, our government should issue general guidelines and invest in developing a system for nutrition in schools,” implored Dr Ali.

In Punjab, the Chief Minister’s School Nutrition Program, which was launched with great fanfare in selected districts, has now completely disappeared into the background. Despite attempts to contact the Education Department for clarification, no information could be obtained about the program's current status.

Commenting on the female malnutrition, former Provincial Health Minister Dr Javed Akram claimed that the government had launched the Punjab Human Capital Investment Project, which would provide medical check-ups, vaccinations, and financial assistance to women in 13 districts.

Conversely, Dr Fazal Majeed, Director of the Nutrition Health Department of K-P claimed that the government had launched the Micro-Nutrient Universal Program in 12 districts, where women will receive essential vitamins, including folic acid supplements, free of cost.