When the distinguished scholar Francesca Orsini arrived at Delhi airport on October 21, 2025, she expected a routine welcome, not abrupt deportation. With a valid five-year e-visa, she was ordered to leave without explanation: a moment that vividly illustrates how contemporary India uses administrative processes to stifle academic freedom. Her removal exposes how bureaucratic procedures now serve to mask and enforce political control, transforming the landscape for intellectual inquiry.

Orsini’s deportation exemplifies a deliberate state strategy targeting intellectual dissent and plurality. Rather than an isolated case, it reflects a broader effort to restrict critical thought and dialogue in India. The choice to exclude a scholar dedicated to India’s diverse literary history demonstrates a regime’s deep discomfort with the very openness that once defined Indian scholarship.

The scholar and the significance of her work

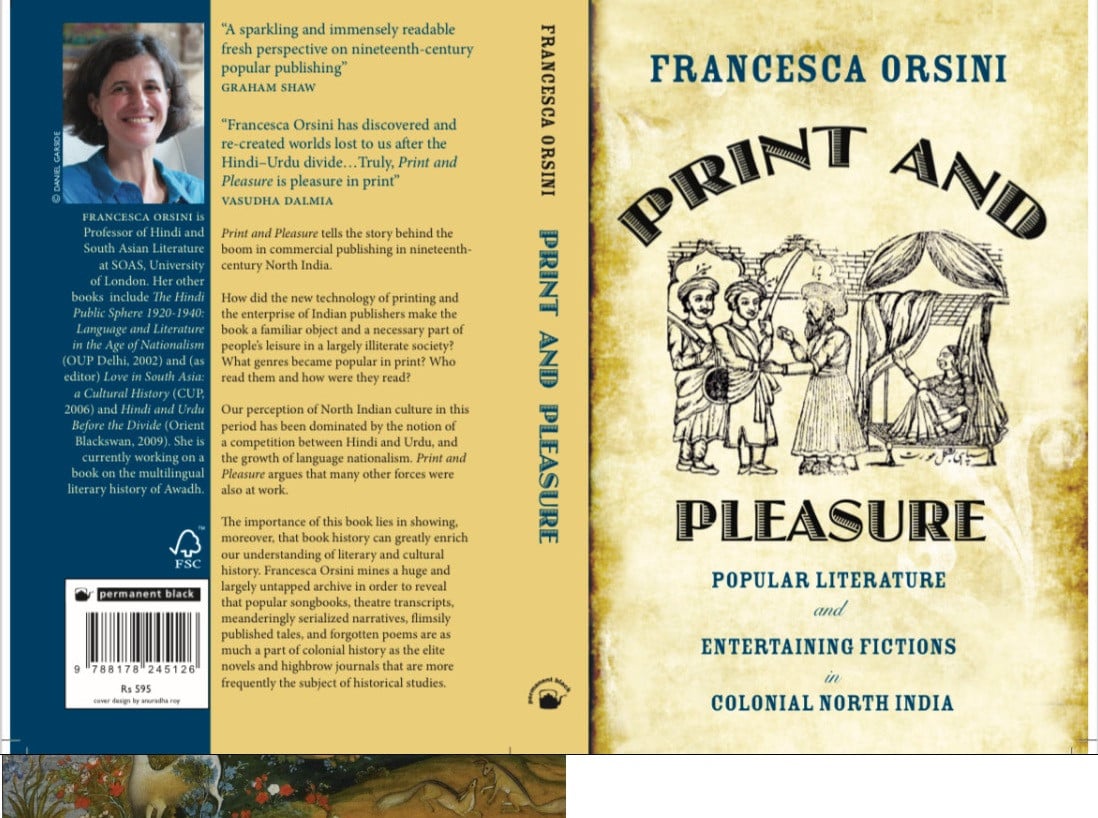

Francesca Orsini is no stranger to India’s cultural world. She studied Hindi at Venice University, at the Central Institute of Hindi in Agra, and at Jawaharlal Nehru University. For decades, she has immersed herself in South Asian literary history. Her works—The Hindi Public Sphere, 1920–1940: Language and Literature in the Age of Nationalism and Print and Pleasure: Popular Literature and Entertaining Fictions in Colonial North India—have deeply shaped modern understanding of Hindi’s cultural and political evolution. Her research highlights the multiplicity of the Indian literary experience: the meeting of languages, registers, and publics that resists colonial and nationalist uniformity.

“I am a literary historian working primarily with Hindi and Urdu materials and interested in exploring how multilingualism worked and continues to work within the literary cultures of South Asia,” she writes about herself. The irony is painful: a scholar devoted to mapping the crosscurrents of cultural dialogue is silenced by a state that has replaced dialogue with decree.

Orsini’s work provokes by refusing purity. She shows that Hindi’s development was not a simple, linear move toward a single national language. It was a contested process shaped by local vernaculars, Urdu, women’s voices, and working-class idioms. Her use of Jürgen Habermas’s “public sphere” challenges the triumphalist narrative of Hindi nationalism. She exposes fractures in the “public,” showing how class, caste, gender, and religion shaped who joined the national conversation.

To deport Orsini is thus not merely to reject a foreign visitor but to symbolically repudiate the heteroglossic, dialogic India that her scholarship so meticulously reconstructs.

Fortress India: From republic to enclosure

orsini’s case is the fourth recent instance of a foreign scholar with valid papers being denied entry to India. In March 2022, British anthropologist Filippo Osella was turned back at Thiruvananthapuram airport with no explanation. That same year, Lindsay Bremner, a British architecture professor, was also deported. In 2024, Kashmiri-origin scholar Nitasha Kaul was refused entry at Bengaluru airport and later had her OCI card revoked. Ashok Swain, a Swedish-based academic of Indian origin, had his OCI status cancelled after criticizing the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

These incidents reveal a deliberate national strategy: India is constructing boundaries not just against physical threats, but also against intellectual diversity. Inspired by the fortress metaphor—where state power seeks to eliminate unpredictability and dissent—India’s new regime of academic gatekeeping is driven more by fear of pluralism than external enemies. Borders now serve to dictate who may participate in the nation’s discourse.

The official reason for Orsini’s deportation—an alleged old visa violation—is absurd. It uses bureaucratic logic to rationalise what is, in fact, political censorship. Michel Foucault’s “governmentality” clarifies this: modern states use not only open repression but also micro-regulation of conduct, movement, and knowledge. Visa categories, conference permits, and security clearances are subtle tools that domesticate intellectual life.

This is the modern face of authoritarianism: not open censorship, but systematic administrative barriers that quietly limit dissent and intellectual freedom. Such tactics aim to redefine the boundaries of permissible thought.

The politics of purity and the fear of multiplicity

The ideological basis of such control is a project of cultural purification in the Hindu-nationalist imagination. The BJP/RSS aims to merge the Indian nation with a Sanskritised, monolingual “Hindi-Hindu-Hindustan.” This idea cannot handle the actual messiness of India’s languages and cultures. In contrast, Orsini’s scholarship celebrates that messiness—the “worldliness,” as she puts it, “of literature both as it inhabits and intervenes in the world.”

In The Hindi Public Sphere, Orsini showed how early twentieth-century Hindi periodicals and pamphlets allowed negotiation between elite nationalism and the energies of women, workers, and subaltern publics. Her scholarship breaks the myth of a unified national culture. It reveals Hindi’s real history as one of hybridity and dissent.

The state’s rejection of Orsini mirrors its broader drive to suppress linguistic and cultural plurality. By excluding a scholar known for exploring India’s hybrid literary traditions, the government symbolically rejects diversity itself. This act transforms a visa denial into a powerful statement about which voices are welcome in public discourse—and which are silenced.

In this sense, India now shows what Arendt called the “paranoid logic of totalitarianism”: the belief that every difference is a conspiracy, and every ambiguity, a betrayal. Intellectuals, especially those of foreign or diasporic origin, are seen as threats because they move between different worlds of reference. Their thought cannot be boxed into loyalty or treason.

Exile, paranoia, and the new cartography of dissent

The deportation of foreign scholars is part of a broader effort to silence domestic dissent. University campuses—once filled with debate—are increasingly watched and policed. Faculty jobs and conferences need political clearance; student protests are criminalised. The state’s fear also reaches those abroad. Overseas Indians who criticise government policies risk losing their OCI cards, cutting off legal and emotional ties to home. This is a new form of exile—one enforced by revoking belonging.

Edward Said described exile as both a condition of pain and of insight: the exile, distanced from the homeland, can see it more clearly. Yet the Indian state’s treatment of its intellectual diaspora reveals a deeper pathology: it cannot tolerate being seen at all. Visibility itself becomes dangerous when power relies on myth.

The fortress mentality, as Achille Mbembe states in his work on necropolitics, is not just defensive; it builds new ways to control. Borders grow inside and outside the nation. They decide who enters and what may be said, taught, or imagined. Airport, university, classroom, and visa office merge into one regime of surveillance.

Comparative horizons: Global authoritarianism and the war on knowledge

india’s intellectual isolationism is not unique. It echoes patterns seen across the world’s illiberal democracies. In China, scholars must navigate a complex system of censorship that extends from the internet to academic publishing. Research on sensitive topics such as Tibet, Xinjiang, or the Cultural Revolution is effectively prohibited. In Turkey, thousands of academics were purged or imprisoned after the 2016 coup attempt. In Russia, the state dictates historical truth through laws criminalizing “distortion” of the Second World War. In Hungary, Viktor Orbán’s government expelled the Central European University, branding it an alien liberal institution.

What unites these regimes is a shared belief that knowledge must be controlled by the state. The drive to police scholarship is not about ideology but about securing epistemic authority. Orsini’s deportation places India among nations that enforce 'epistemic authoritarianism'—governments ruling reality by deciding what knowledge is permitted.

In each case, the state’s hostility to critical thought is disguised as the defence of sovereignty. The right to control narrative is recast as the defence of the nation’s honour. This inversion of meaning is what George Orwell diagnosed as the essence of political language in totalitarian societies: to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable. India’s treatment of foreign and domestic intellectuals follows precisely this logic. Censorship is rebranded as vigilance; exclusion becomes patriotism.

The Erosion of the Public Sphere

From the standpoint of political philosophy, what is at stake is the very possibility of the public. Habermas envisioned the public sphere as a space where rational-critical debate could shape political will. In the Indian context, that sphere has always been precarious—structured by inequalities of caste, gender, and language—but it existed, nonetheless as an aspiration. Today, the deliberate narrowing of discourse, the criminalisation of dissent, and the manipulation of media have eroded that fragile ideal.

Orsini’s own historical reconstruction of the Hindi public sphere showed how linguistic and literary debates once fostered a sense of collective reasoning. By silencing her, the state symbolically forecloses that possibility in the present. The public sphere is replaced by a pseudo-public, a performative unanimity maintained through fear and propaganda. Foucault would call this the transformation of discourse into regime: language ceases to be a medium of critique and becomes an instrument of control.

In such a regime, even academic inquiry is redefined. Knowledge that does not serve the nation’s ideological project is deemed “anti-national.” Universities are turned into ideological training grounds. Funding priorities shift from critical humanities to technocratic nationalism. The intellectual, once a figure of questioning, is recast as a potential insurgent.

The human condition and the politics of plurality

The deeper tragedy of this transformation is not merely political but ontological. Arendt, in The Human Condition, argued that the essence of human freedom lies in natality—the capacity to begin anew, to introduce unexpected words and deeds into the world. Totalitarianism seeks to extinguish that capacity by rendering all speech predictable and all action predetermined. When the state dictates who may think or speak about its culture, it denies not only freedom of expression but the human condition itself.

India’s intellectual tradition has historically thrived on openness: the debates of Nalanda, the syncretism of Bhakti and Sufi poets, the heterodox dialogues of Ashoka’s edicts, the vernacular cosmopolitanism of early modern Awadh—the very subject of Orsini’s current research. To close the gates on such a scholar is to close the gates on that history. It is to forget that India’s greatest strength has been its ability to contain contradictions without resolving them by force.

A culture that fears scrutiny is a culture already hollowed from within. The fortress may appear impregnable, but as Arendt noted, totalitarian isolation leads not to strength but to decay: “The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction no longer exists.” The systematic manufacture of ignorance—through censorship, propaganda, and exclusion—produces precisely that subject: obedient, unthinking, and docile.

Toward an ethics of intellectual openness

The challenge, then, is not merely to protest isolated acts of deportation or censorship, but to re-articulate an ethics of intellectual openness. In a world increasingly defined by borders—physical, digital, epistemic—the defence of scholarship becomes an act of moral resistance. The scholar, as Said insisted, must remain a “secular critic,” one who speaks truth to power not from within the fortress but from the threshold, the in-between space of dialogue.

Defending such thresholds is not an academic luxury; it is a civilizational necessity. The expulsion of a scholar of Hindi is not only an insult to global academia but an injury to India itself. For it signals a nation turning against the very principles—plurality, curiosity, debate—that once defined its greatness.

If India continues down this path, it will find itself isolated not by Western conspiracy but by its own fear of freedom. The fortress, after all, imprisons those who build it.

The meaning of a border

What has been deported from India is not merely a person but an idea: the idea that knowledge is porous, that culture thrives on exchange, and that the nation is strongest when it listens to those who see it from without. To restore that idea will require courage—not the muscular nationalism of slogans, but the quiet courage of conversation.

In the end, the question is philosophical: Can a nation built on fear of difference survive the loss of dialogue? Arendt would answer no; so would Habermas, Foucault, Said, and indeed Orsini herself, whose work teaches that literature lives only in conversation with the other.

India must decide whether it wishes to remain a living conversation or become a sealed archive guarded by suspicion. The deportation from Delhi airport is not an end—it is a mirror held up to the world. And what the world sees in that mirror is a republic struggling against its own shadow.

Aftab Husain is a Pakistan-born and Austria-based poet in Urdu and English. He teaches South Asian literature and culture at Vienna University

All facts and information are the sole responsibility of the writer