In the words of Indian Air Force pilot Abhinandan Varthaman, arrested by Islamabad after foiled Balakot strikes in 2019, the tea in Pakistan is "fantastic".

The act of serving tea to even those we consider our enemies in hospitality sheds light on how important chai is to Pakistani people. The per capita consumption of tea in the country was estimated at 1.2 kilograms annually in 2023, making Pakistan one of the highest tea-consuming countries globally.

Many refer to tea as Pakistan’s national drink, but most of the chai consumed in Pakistan is not grown here. In 2023, Pakistan imported $611 million worth of tea, making it the largest tea importer worldwide. So where does chai come from and what has it done wrong?

Colonial past

Chai has neither Pakistani nor Indian origins. “Tea wasn't really commonly had in South Asia. There were some groups that drank tea but it wasn't widespread until recently in World War I,” says Professor Erica Rappaport, a professor of history at the University of California in Santa Barbara, and author of A Thirst for Empire: How Tea Shaped the Modern World.

Tea was introduced to England in the 17th century by Portuguese princess Catherine of Braganza. Her fondness for tea made it popular in royal circles. Growing distrust of its Chinese origins though and rising import costs pushed Britain to cultivate its own supply, with Queen Victoria ordering tea cultivation in British colonies. The East India Company sent agents like Robert Bruce and Robert Fortune, who famously smuggled tea seeds from China to India.

“The British did establish plantations and discover tea growing in Assam in the Northeast in the 1820s. Then they tried to do plantations in the 1830s but the tea was so bad, it really didn't take off or compete with Chinese tea at all at first,” said Rappaport, in an interview over zoom.

This colonial project relied on brutal opium farming in Bengal to fund the trade and sparked the Opium Wars in China to eliminate competition.

Tea estates were established in Assam and Darjeeling in the 1800s, but Indians didn’t start drinking tea widely till the 20th century. “The British initially grew it as a cash crop for export exclusively. They had no interest in selling it to South Asian people at all. It was only when the crop became so huge and the international market became sluggish that they began to seriously investigate the possibility of marketing it within the subcontinent,” said Philip Lutgendorf, a former professor of Hindi and modern Indian studies at the University of Iowa, speaking to The Express Tribune.

British-led Indian Tea Association launched aggressive campaigns during World War I, setting up stalls in factories and sending marketeers to promote tea at home. Vendors at railway stations created masala chai by adding spices and milk, ignoring British recipes.

Marketing gimmick

The Indian Tea Market Expansion Board used a variety of tactics to launch a public relations campaign to get people to drink tea. Vans would go into towns and bazaars and give out free samples of tea. They had special color-coded cups for Hindus and Muslims and Christians, so no one was drinking from a cup that had been used by a person of a different community. They also had women-only vans that would go into houses to teach Indian women how to make tea.

Tea marketeers are among the most advanced in the industry. They were competing with the Chinese and wanted to position the product as South Asian. They also had to address surplusses — while other produce such as grain can be stored till prices go up, tea cannot be preserved. Tea, you can't really turn it into anything else. It's just a drink. So what the industry had to realize is that we need to make more consumers, we can't find more uses for surpluses," said Rappaport. "So they got very good at marketing tea in different ways, trying to increase people's individual consumption, but also finding new people to drink tea.”

Despite the push by British martketeers to later frame tea as a "swadeshi" [nationalist] drink, chai's colonial lineage is well known.

Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah and Jawaharlal Nehru, principal leaders of the independence struggle against the British, shared a love-hate relationship with tea. They recognised tea as a cash crop intended primarily to mint money for the British and acknowledged calls for its boycott. Yet, they themselves belonged to elite tea-drinking groups.

Mahatma Gandhi was entirely not a fan of tea and openly advocated for its boycott.

“During the independence struggle, [tea] promotion really fell apart. It wasn't until after [1947] partition and independence, when many of the tea estates themselves began to be run by South Asians. Then again the marketing campaign was ratcheted up,” says Lutgendorf, who has taught Hindi at the university level for 33 years and had written about tea's cultural history in South Asia.

“Right at independence, there's another debate: should we just kick out this whole industry? But by that point, there are a million tea workers. Our economy is going to collapse if we don't keep it. So they kept the industry and then just marketed it so intensely as nationalist, swadeshi, local,” adds Rappaport.

“I think advertisements can be very misleading. There's nothing nationalistic about it,” countered renowned Pakistani-American cultural historian Ayesha Jalal. Brands often work towards glamourising their products and sweeping their histories and production lines under the rug.

“Companies do not want people mulling over where their goods come from, and what sort of poor people work to produce them, and what the history of oppression that might underlie their production is,” seconded Lutgendorf.

By the late 20th century, domestic consumption had grown such that most locally grown tea never made it out of India.

Reclaiming chai

Some argue that the popularity of masala chai was a form of colonial resistance. By adapting the drink to local tastes, the Indian subcontinent had reclaimed chai.

“The British were like it's unclean. They're not making the tea properly. They might hurt the brand because it's not made the way that we expect it to be made. And they passed adulteration laws and said all kinds of things to try to keep the pure British style tea,” says Rappaport.

The act of consuming tea is hardly a form of resistance though, counters Jalal. “As a legacy of colonialism, I don't understand where the resistance comes in. Because we are, if anything, dependent on tea, and that too, a la British, as the mode of drinking it.”

Tea is not as local or indigenous as Pakistanis commonly percieve. “People think it's their local traditional drink, but it wouldn't exist without all the trade routes that have gone back for centuries,” said Rappaport. “It has to do with class either because the way tea is drunk, in British style, with British cups, was [then] an elite practice, particularly associated with Bengal.”

How's the tea?

Historically, tea-drinking nations such as China, Turkey and Russia, don't add milk to their tea.

Tea became intertwined with poverty in Britain as the addition of milk and sugar was a way of increasing its nutritional value and staving off hunger. “It's a drug that keeps the labourer satisfied without really doing anything. So it's quite superficial,” Jalal pointed out.

“There's a somewhat different history [in Pakistan] because of much greater tea consumption in the Muslim world, tea having been considered halal in Islam from early on,” says Lutgendorf. “There was some tea consumption in Mughal courts, but this tea was imported from Iran and ultimately came from China. It was not South Asian in origin. It was very expensive and it was drunk as a luxury good by a very limited range of people and was considered medicinal.”

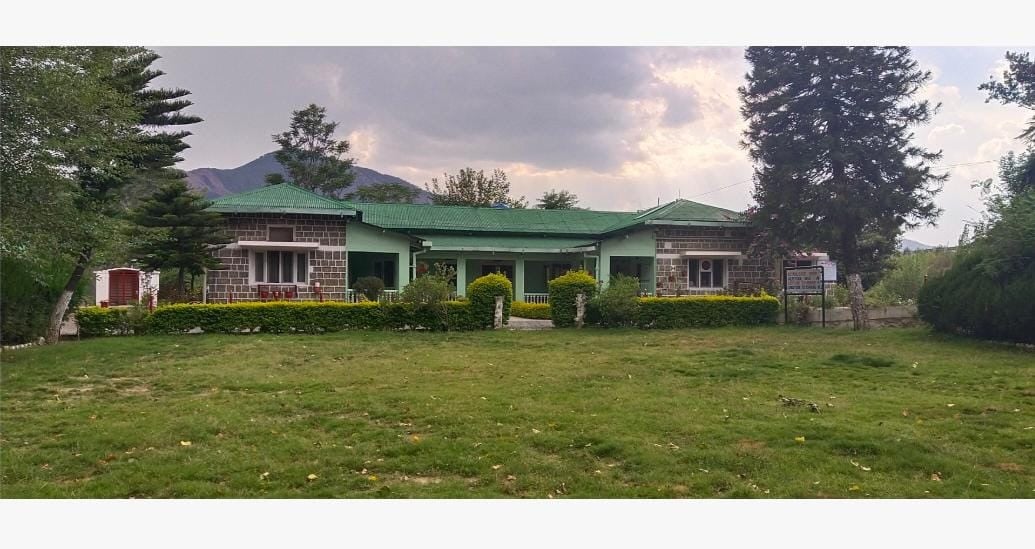

A Lipton tea processing farm in K-P's Mansehra. Photo: The Express Tribune

While the majority of India was introduced to tea by the British, in Karachi and in areas connected to the Silk Road it was Iranian immigrants who brought tea to the people.

“Irani cafes get their start much earlier than the main marketing of tea,” said Lutgendorf. “Zoroastrian refugees from Iran, who came to South Asia and settled particularly along the West Coast were able to create little restaurants and bakeries. They were tea drinkers from Iran.”

These cafes were an important social space for the lower middle class, particularly people who lived in tiny apartments and flats. “They didn't have a lot of space of their own, but they could go out to these Irani cafes. And for the price of a cup of tea, they would have a table, and they could meet with their friends,” according to Lutgendorf.

It was a very important gathering place for writers, intellectuals, all kinds of people. Today, only a handful of these Irani cafes remain, replaced by Afghan, Pathan and Baloch chaiwallahs and dhabas.

Bitter tea

British tea cultivation thrived on exploitative, indentured labour, a system only slightly better than slavery. Tea from Assam became known as "bitter tea" given the suffering behind its production.

Workers, often entire families from Nepal and tribal areas, were bound by strict contracts and brutal conditions, where in women and children would be picked for plucking, face long hours, poor sanitation, and negligible medical attention. Coolie catchers hunted runaways and the militia prevented families from escaping.

They would conflate the act of drinking tea with drinking the blood of your brothers, when referring to tea labourers, said Rappaport.

“It's a holdover from the colonial period that you have these very large tracts that are basically plantations. They call them gardens. That is euphemism from the colonial period to make it seem nicer. Plantations are associated with hard labour. Gardens are associated with ladies clipping flowers,” seconded Lutgendorf.

These conditions still exist on plantations today. “The exploitation of labour persists. That is inherent in capitalism's desire to grow. We have persisted with labour laws that are basically from the colonial period, we haven't done much to give labour rights,” added Jalal.

Daily-wage labourers are hired on seasonal basis — primarily April to October at a rate of Rs15 to 20 per kilogram of tea leaves picked, says Pakistan Institute of Labour Education and Research (PILER) Co-Director Abbas Haider, telling The Express Tribune about labour conditions at tea plantations across Pakistan.

Apart from the meagre daily wage, the workers are given no benefits, let alone healthcare. “These workers are employed under vulnerable and precarious working conditions. They are also deprived of the fundamental right to organize,” said Haider.

During World War II, men were recruited to fight and women were left to tend to plantations. This practice continued after the war. “Women workers were there with their baskets. It's a backbreaking labor,” adds Jalal. Sexual violence is also rampant at these plantations.

The unfair distribution of labour and exploitation of workers does not end at plantations.

Around 16 tea labourers recently filed a case for wrongful termination against Lipton after it shut down its tea processing plant in Mansehra, Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa (K-P) without notice.

“I’m worried that if they find out, they might come after us — they’ve already bribed judges before. In Islamabad, they even bought a three-judge bench to cancel our stay order. So if they owe us, say, Rs25 million in total, it’s easier for them to just bribe a judge with Rs10 million and get the case thrown out,” wrote S, one of the petitioning labourers, over Whatsapp, speaking to The Express Tribune on the condition of anonymity.

“Money is not an issue for them, they can keep this case going for 10 years. But we are working-class people. We’re just trying to survive, especially since we’ve lost our jobs. Some of us couldn’t even afford to continue the case. So when the company opened talks, we agreed, we said we’ll withdraw our case if you pay us.”

Before being laid off, S and his colleagues were paid minimum wage, received no bonuses and could not take more than a day off per month. The meagre health insurance they had lasted only two years. If they dared complain about a supervisor, they were fired on the spot.

“Each person was often assigned three, four, or even five different kinds of responsibilities. All of us were doing more work than we were paid for,” said S. “Our salaries were too. We would sometimes be paid on time and at other times not."

The company did nothing to prevent accidents, or even respond to them when they occured. "If someone died on site, their family recieved no compensations," according to S.

Workers were not even permitted to greet Lipton officials, let alone voice their concerns. "If anyone tried, the supervisor would report them and harass them further.”

At least one such incident, where a worker lost his fingers in a machine, was covered up. “Lipton didn’t even care about us before the case. They are a big company, they don’t care one bit about workers. Their officers just want to keep workers down, exploit them, and get rewarded for it,” said S.

On paper, plantation owners are supposed to provide benefits including housing, food ration, health and education for children. They use this to get away with paying below minimum wage. But given weak legislation, these benefits are the easiest and cheapest to forget, says Sarah Besky, a cultural anthropology professor at Cornell University and author of The Darjeeling Distinction: Labor and Justice on Fair Trade Tea Plantations in India.

"It's easier to manipulate women because of the fact that their job is tied to their house. No house, no job, no job, no house," said Besky, over a zoom call. This makes it easier to silence women who have been subjected to sexual assault.

Undercooked sector?

Despite the massive potential of home grown tea in terms of generating employment and reducing dependency on imports, the tea sector remains low on the government's priority.

Climate change has significantly impacted production with the number of tea bushes decreasing. However, plantation workers are frequently held responsible for this loss. “With climate change and increasing heats, this is becoming just a really, really tiring and hard job,” said Sarah Besky, over zoom.

"It's somewhat Sisyphean. It's a whole system of exploitation.The plantation system is the problem. It is a fundamentally unequal system,” says Besky, clarifying that individual bad actors are only but a part of the problem.

“There's all of these discursive moves to make us feel good about the tea that we drink, whether it's fair trade, whether it's organic, whether it's thinking about grandmothers making chai very lovingly,” said Besky.

Fair Trade Certified standards are supposed to guarantee safe, healthy workplaces, ban forced labour, child labour, ensure fair pay and uphold environmental safeguards with full product traceability. “The idea of fair trade is that it gets workers more money, but show me the proof that it gets workers more money. It’s obviously a marketing tool,” according to Besky.

“The tea is cheap and the workers are very poorly paid. It's so cheap and so hard to convince consumers that they should pay more for it,” added Rappaport.

It all boils down to land

What would justice look like for tea labourers today? Land reform is the answer, says Besky.

By shifting land ownership and control from large estates to small farmers or indigenous communities can lead to fairer land distribution and support local economic advancement. It can also encompass changes to land tenure, tenancy terms and facilitate easier access to resources.

Tea plantations in Mansehra, Swat and Azad Kashmir do not sufficiently meet the demand for chai in Pakistan. Hence, most tea locally consumed is imported.

“Tea import cost makes it one of the top non-oil import burdens. It compounds pressure on forex reserves already strained. Price volatility exacerbates this,” said Dr Vaqar Ahmed, an economist specialising in trade policy in Pakistan and South Asia.

“It's a drag on our economy,” agreed Jalal, referring to imports. “The reason why Pakistan's economy is in the doldrums is that we don't produce. Tea is an example.”

“Climatic conditions in key tea-growing regions are far more suitable, and our limited domestic production, confined mostly to northern areas, meets barely 10% of demand. Historically, consumer preference for imported varieties and weak investment in tea cultivation have perpetuated reliance on imports,” said Ahmed.

Ahmed listed low yeilds, lack of research, no development support and high upfront costs as structural factors preventing Pakistan from sustaining a thriving local tea industry.

Moreover, colonial-era trade patterns have shaped Pakistan’s reliance on imported tea. Pre-partition colonial policy entrenched tea as a mass consumption good while discouraging local production to protect imperial trade.

“Post-1947, Pakistan inherited both the demand and the supply chains, without pivoting to self-sufficiency,” notes Ahmed. Modern trade policies have also failed to reduce this dependency. “Trade agreements, such as PTAs with Indonesia and Sri Lanka, focus on tariff reductions, not diversification or domestic capacity. The Anti-Smuggling Act of 2023 targets informal tea trade but doesn’t address root causes,” he added. “Local production may not sustain without subsidies which may not be allowed by the IMF [International Monetary Fund].”

Is shifting domestic demand for tea to something else locally produced an option? Ahmed says no. “Promoting substitutes like herbal drinks would require aggressive marketing, likely led by the private sector.”

But policy interventions such as divesifying import sources, to include Vietnam and Indonesia for example, via preferential tariffs, investing in climate-resilient tea research and developments, and establishing "tea zones" in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa with corporate buy-ins could help, said Ahmed.

Chai may be a staple in our homes but that does not erase its colonial and capitalistic roots. “You want a cup of tea? Think about where it came from. Sit with your complicity,” says Besky.

“What can a powerless person do? If he speaks up, he suffers even more,” says S. It is crucial that if we continue consuming this beverage, we also try our best to give a voice to those who have lost theirs in the process of getting it to us.