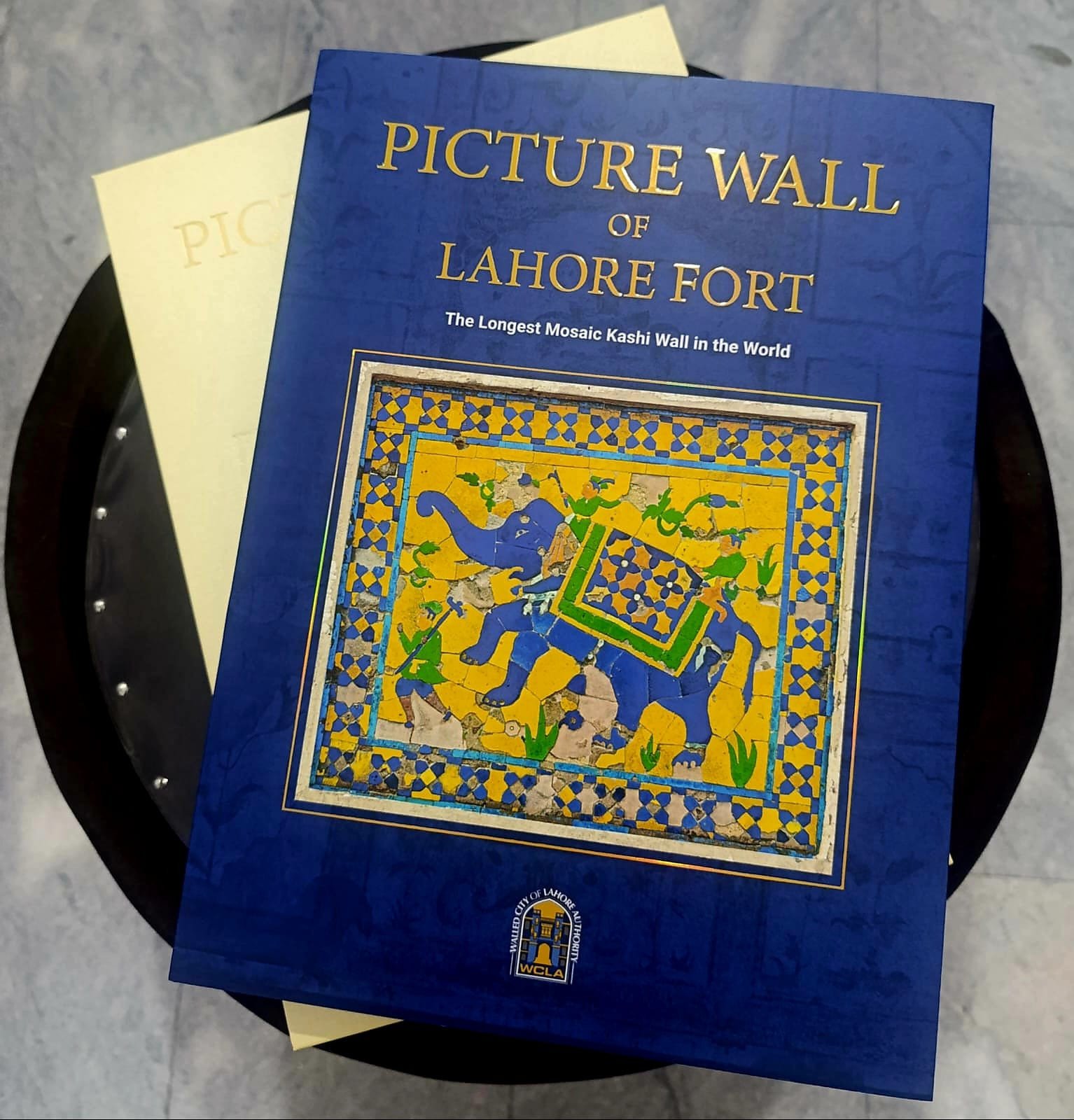

The Lahore Fort is one of the city’s most majestic treasures, steeped in centuries of stories and splendour. Yet among its many wonders, the outer Picture Wall feels like a world of its own — a mosaic of colour and history stretching as far as the eye can follow. In her illuminating book, Picture Wall of Lahore Fort: The Longest Mosaic Kashi Wall in the World, Prof Dr Kanwal Khalid rekindles these memories and answers long-standing questions that linger around this remarkable landmark.

The visitors of the Lahore Fort, in addition to being overawed by the grandeur and monumental scale of the Fort itself, were intrigued by the number of small pictures [comparatively speaking], which include illustrations of animals, humans, imaginary creatures, depictions of love, hunting, life, war, demons and dragons. It was indeed a cornucopia of images, both real and unreal, that raised more questions than it could reply to.

Starting as early as 1948, I recall being fortunate to visit the Fort many times during my childhood with my family. My younger brother and I had become familiar with all the nooks and corners of the Fort, which used to be far more visitor-friendly at the time. One of our favourite disappearing acts [from the family] was to go down the turret staircase in the Akbari quadrangle. We went down unimpeded till we reached the door that allowed us to get out and see the fort from what was once the riverbed. This was the space between the outer fort wall and the fortification behind that was built later.

Here the innumerable pictures on the outer wall at the different levels would mesmerise both of us. Some, we were able to look closely while the large number were beyond our immediate reach. However, the overall impact hypnotised us with imagery and colour. The wall was simply dazzling and at the time, they looked freshly finished. Our eyes would move from picture to picture, trying to find something that we could clearly understand. The animals thrilled us as we named them and then there were so many that we had no idea about. The Wall has indeed intrigued people for more than 400 years. It carries the viewer from the real world to the world of the unknown.

It was much later that I became an architect and a teacher. It was an utter delight to conduct my classes inside the Lahore Fort, how could there be a better setting? We roamed around the Fort and somehow always ended up in that quiet space, between the Wall and fortification, gazing up at the pictures on the Wall. Here, I usually lost the students who were intrigued and curious as they walked, often ran, from picture to picture. The Picture Wall was a great stimulus to creativity, discovery and imagination. The Wall fulfilled this function of educating my young students and this was the best I had hoped. Perhaps that had been the purpose of the Wall all along, not only to dazzle but to educate and provoke the imagination onto greater and greater heights.

The earliest scholarly work on the Wall was done by Dr Jean Phillippe Vogel, a Dutch Indologist in 1920, who spent many years working in India with the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) in various positions. It has taken one hundred and four years for a similar work to appear, a great credit to the writer.

Prof Dr Kanwal Khalid has now helped us to understand this enigma, a jigsaw puzzle, as she calls it. With her groundbreaking book Picture Wall of Lahore Fort: The Longest Mosaic Kashi Wall in the World, she has provided a historical analysis of the various and numerous representations of the flora and fauna of North India. She has brought to the subject an academic brilliance, and an analytical mind with tenacity to hold on to a clue until it is satisfactorily solved. She has also pointed out the outlines of future research work on the subject. The book certainly is of immense value to students, scholars and researchers.

Fulfilling a dream from her student days back in the 1990s, she has now not only studied the Picture Wall, analysed it but also published her scholarly findings for the benefit of present and future generations. Dr Khalid brings clarity with intelligent interpretation of symbols and elaboration on the meaning, both hidden and evident.

The Punjab was once a great highway over which traversed scholars from China in search of Buddhist learning and philosophy. Alongside the scholars came the traders and mendicants, exchanging goods and knowledge with the highly literate society of Punjab of the time. People of learning and the craftsmen of Punjab carried the memories of the time long gone by and expressed themselves accordingly in art. Dr Kanwal points to this collective memory as she draws our attention to the dragons, which formed a part of the Chinese belief system but were not found or spoken of in India.

The designer and the craftsmen of the period were obviously sensitive to their own surroundings and environs but also they were aware of the influences from outside of the subcontinent.

The book is handsomely produced, well-illustrated, convincingly argued, yet an easy read. Not only Lahoris, but all those who are interested in the tangible and the intangible heritage of Lahore, will benefit from this collection of art and tales. Students and scholars, researchers and conservationists, craft-persons and artists will find this book an immense treasure for their learning in the present, as well as for their work in the future.

The conservation project of the Lahore Fort's Picture Wall and the publication of this book have been carried out by Aga Khan Cultural Service Pakistan, Walled City of Lahore Authority, The World Bank, Punjab Tourism for Economic Growth, the Norwegian Embassy, the German Embassy, and the US Embassy.

Prof Pervaiz Vandal is an architect and historian

All facts and information are the sole responsibility of the writer