The match had already stretched into its tense final minutes. Mohib* sat on the edge of his bed, eyes fixed on the phone, the familiar green fields of Erangel opening up across the screen. His teammates shouted instructions through their headsets, each one urging him to push forward, to survive long enough to take the chicken dinner. But his character was cornered with little to fight back. No scope on the rifle, no upgraded helmet, no flashy skin that marked him as prepared. The game offered him a way out, not through skill but through a small, glowing button that pulsed on the screen. “Buy UC.” The three letters had become their own language. With UC, or Unknown Cash, he could purchase a better weapon skin, unlock crates, or even buy the outfit his friends had been showing off in earlier matches. Without it, the round would end, and he would once again be the one left behind.

It was not just about winning. PUBG had made it about belonging. In the digital lobbies where players gathered before each match, the skins and outfits told their own story. Those with the glowing masks, rare parachutes, and premium weapons were treated differently. Those without them blended into the background, marked as outsiders. For Mohib who is trying to keep up with his friends, the pressure to spend was subtle but constant. The “Buy UC” prompt was not just a suggestion. It was the doorway to staying in the game.

At home, the buzz of a bank alert told another story. His father picked up his phone to see a charge he could not place. The name of the merchant meant nothing to him, yet the deduction had already been made. It was not a large sum, but enough to make his pause. He had never approved his card to be linked with a game. He had never imagined that something downloaded for free could carry such a price. When he asked his son, the answer was simple, almost too easy. Everyone had UC. Everyone had skins. Without them he stood out. The teasing was subtle, the exclusion quieter, but it was there.

For the parent it was a shock, a reminder that the glowing buttons on a game screen were tied to real money and real bills. For the teenager it was survival in a world where appearance carried as much weight as ability. The UC was more than currency. It was status, a ticket into the circle, a way to keep playing on equal terms. And somewhere in the gap between a free download and an unexpected bank alert, the game had turned into something more than entertainment. It had become a transaction.

PUBG is only one example. There are thousands of games that arrive on the phone for free but are built in a way that sooner or later pushes players toward in-app purchases. For parents, the worry is no longer limited to an unexpected charge on their card. It is also the question of what happens if they refuse. A child’s desire for digital currency does not disappear with a parent’s “no.” In a world where strangers on the internet can exploit that need, the fear grows sharper. What if someone promises UC or diamonds in exchange for a picture, a favour, or an action that could lead to something far worse than a bill?

The business of Free-to-Play

On the surface the idea of free-to-play looks like generosity. The game is free to download, free to start, and free to share with friends. That is what pulls in millions of players. But once the first matches are played, the real model shows itself. Every step has been designed so that progress slows down just enough to make the small button at the corner of the screen feel like the only way forward. The button never asks for much. Just a handful of coins, a few diamonds, a little UC, some lives to play next round. And just like that, a free game begins to earn.

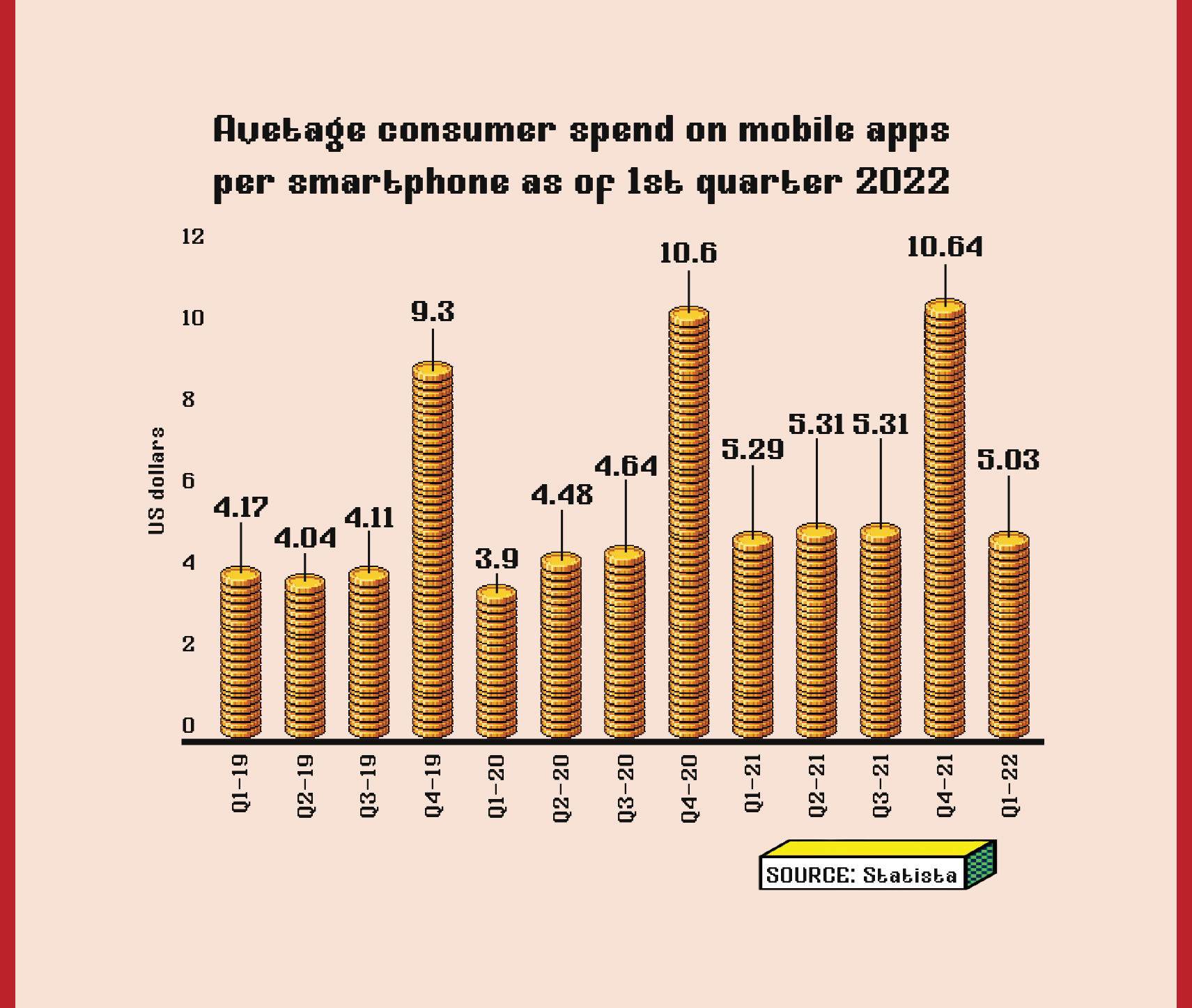

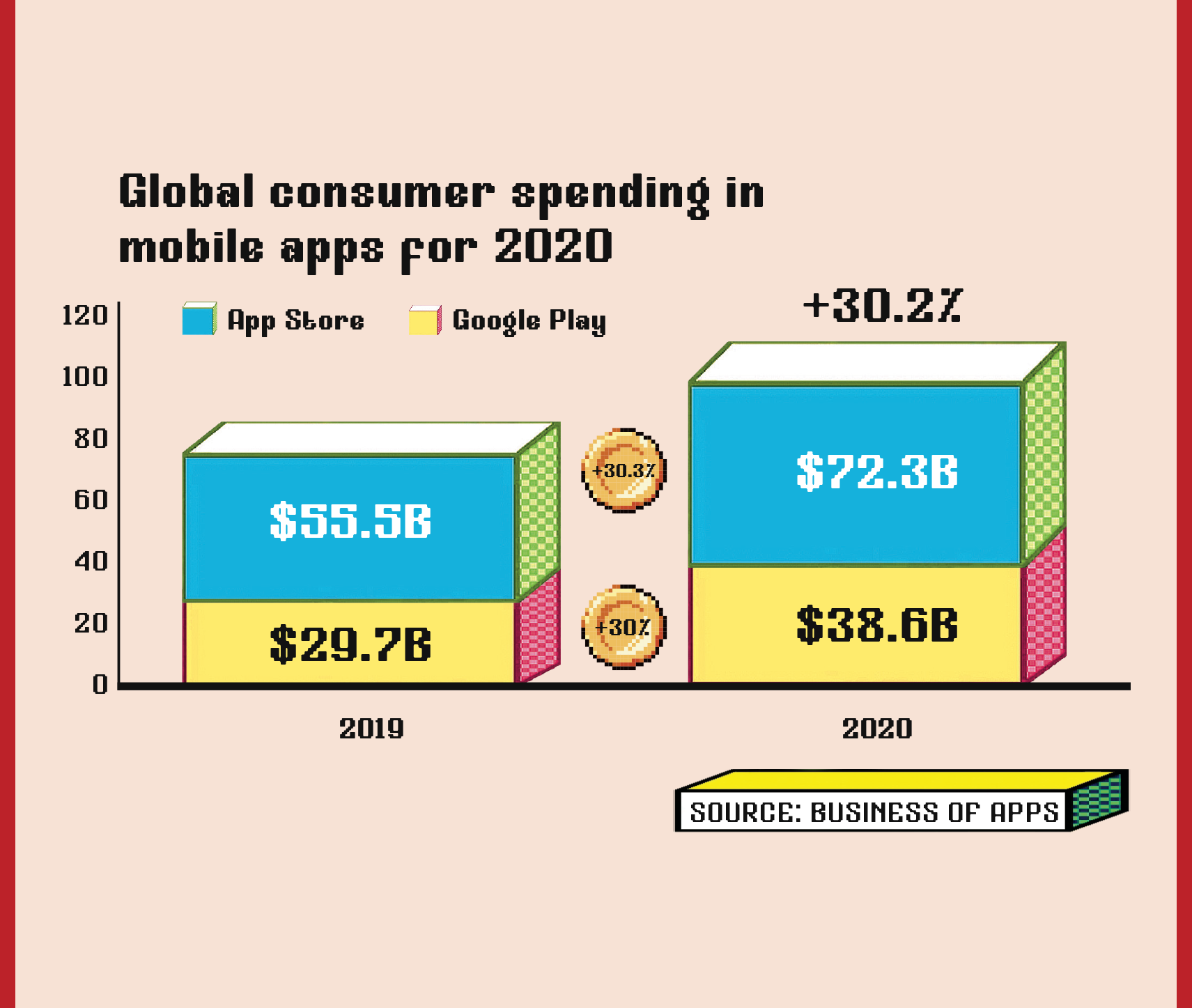

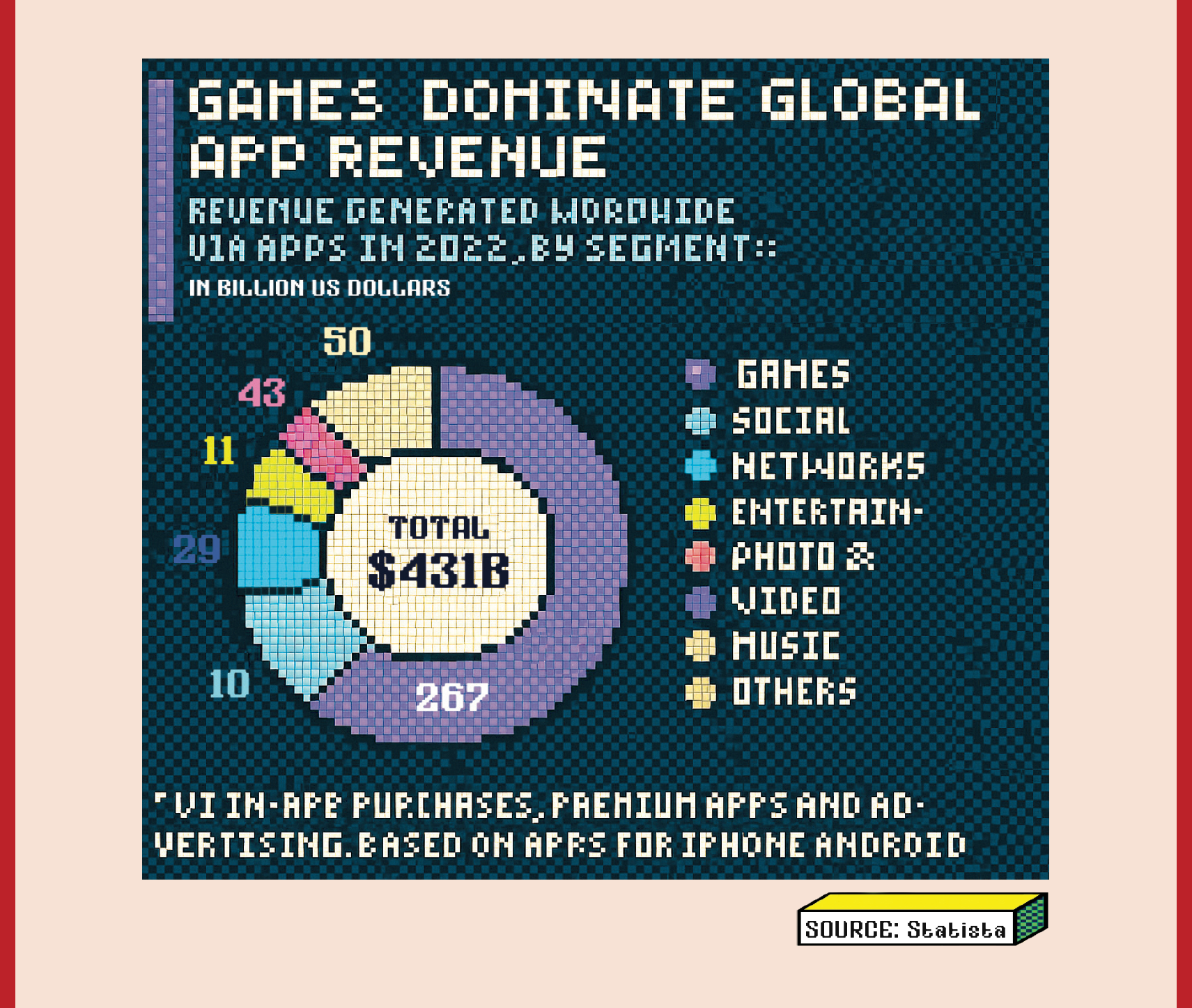

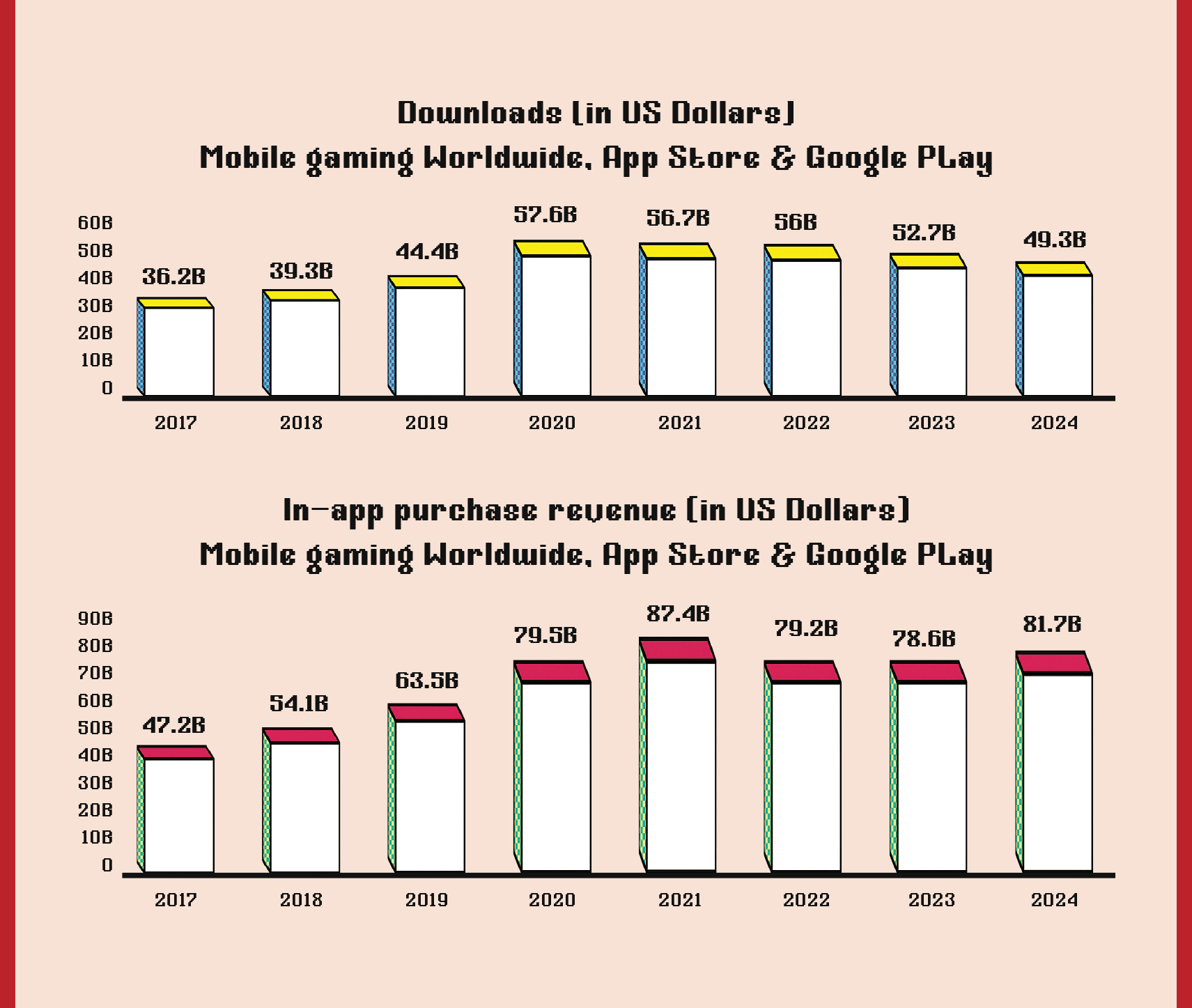

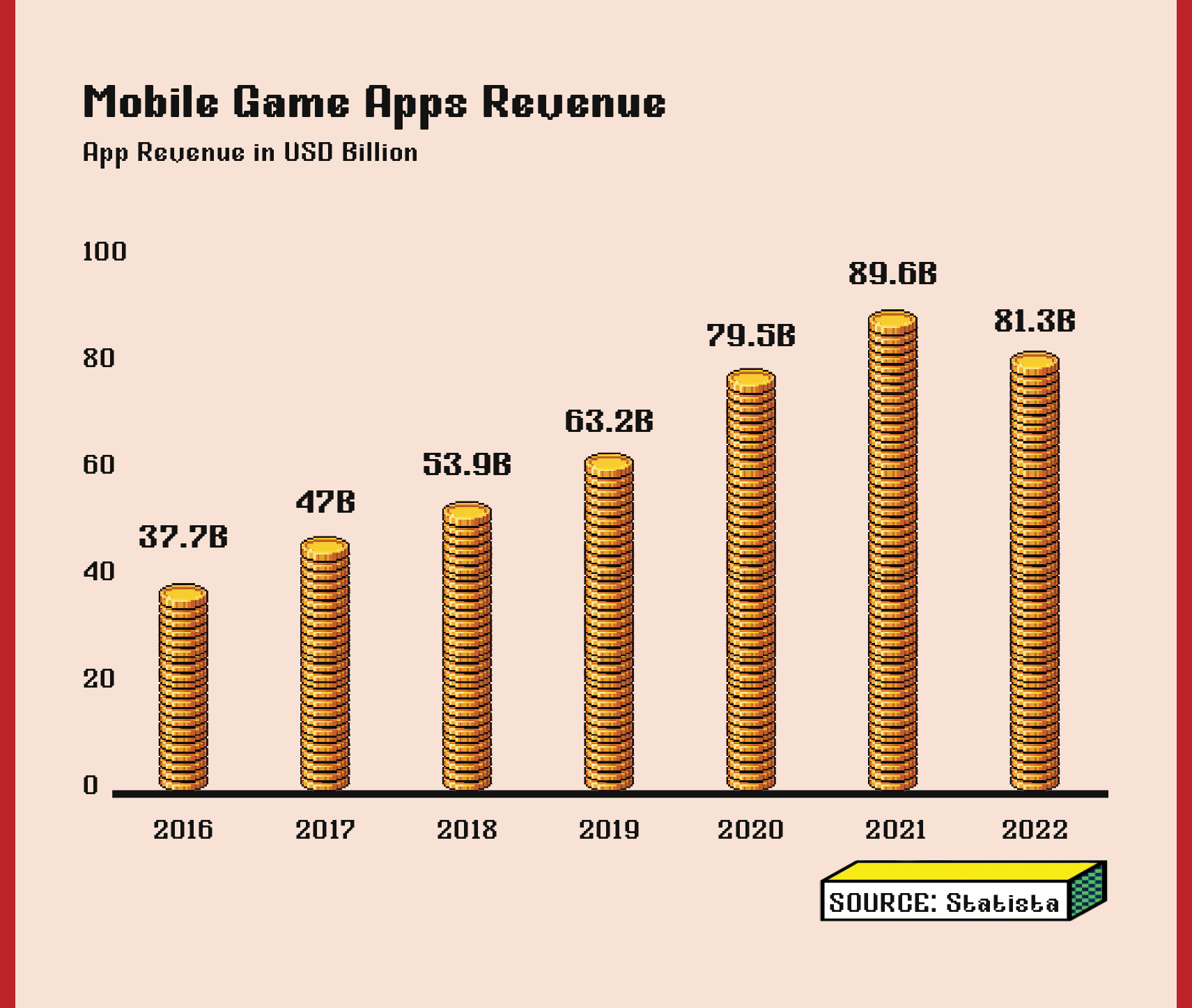

The figures are staggering. Globally, in-app purchases in mobile games brought in more than 80 billion US dollars in 2024. Almost half of all mobile app revenue now comes from these purchases, leaving ads and paid downloads far behind. In some reports, games account for nearly two thirds of the overall app economy.

The way this system works is simple but effective. A huge number of players never spend a single rupee. They download, they play, and eventually they leave. A smaller group makes an occasional purchase, often just a few dollars. And then there is the group that the industry quietly calls “whales.” They are the players who spend far more than the average, sometimes thousands of dollars a year, carrying the entire business on their shoulders. Studies show that one percent of players can generate almost sixty percent of a game’s income. The design of free-to-play games is built with this in mind, making sure there is always another offer, another crate, another skin to keep the big spenders hooked.

The examples are everywhere. PUBG sells UC, or Unknown Cash, that buys weapon skins, outfits, parachutes and seasonal passes. Candy Crush has its own system, offering extra lives and boosters that make an impossible level suddenly easy. Each of these purchases looks small in isolation. A hundred rupees here, two hundred there. But at scale they form an ocean of revenue, larger than the earnings of many traditional entertainment industries.

In Pakistan, this model has taken hold with surprising strength. Teenagers without credit cards have found workarounds through mobile wallets and resellers. Easypaisa and JazzCash are now common methods for topping up UC. Facebook groups, local sellers, and online stores like Daraz openly advertise packages, selling virtual currency in exchange for cash transfers. In some cases small shops act as middlemen, allowing children to pay in notes and receive a code they can redeem online. The infrastructure has grown in step with the demand. What used to be an occasional luxury is now part of everyday play.

The free-to-play economy is therefore not just global but deeply local. It reaches into living rooms in Karachi and Lahore, into small towns where boys gather in gaming cafés, and into WhatsApp groups where links to UC resellers are shared like secrets. Behind every purchase, no matter how small, lies the same principle. The game is free to start, but progress comes at a cost.

Designed to spend

The screen never says it out loud, but the design makes it clear. Free games are not only about play, they are about staying long enough to feel the pull of the purchase. Every tap, every pause, every glowing button has been shaped to keep the player in a cycle that ends with spending.

The most common trick is scarcity. A weapon skin that appears only for a few days, a crate that vanishes if not opened by midnight, a countdown timer that ticks louder as the minutes run out. It is a design that tells the player this is the only chance. Miss it now and it may never come back. The truth is that another offer will always appear, but in the moment the fear of missing out takes over. The player taps to buy not because the item is essential, but because the chance of losing it feels unbearable.

Then comes the slow grind. Games often begin by handing out rewards freely, showering the player with easy wins and fast progress. But as levels increase the pace changes. Lives run out faster, upgrades take longer, matches grow harder. The frustration builds. And just when it feels impossible to keep playing, the screen offers a small relief. Pay a little, unlock the booster, get back into the fight. The purchase is sold not as luxury but as escape.

These tricks work because they feed into human psychology. Every win, every chest opened, every new outfit claimed releases a small burst of dopamine, the same chemical that rewards eating or laughter. The colours flash, the sounds ring, the brain lights up. The player feels good for a moment, and that moment is tied to the purchase. It becomes easy to chase that high again and again, even when the reward is only pixels on a screen.

A behavioural psychologist Dr Sharmeen Pervaiz explained that these games borrow techniques straight out of gambling halls. “Every time a player unlocks a crate or sees a countdown timer, the brain responds with the same urgency and reward patterns we associate with slot machines. Children and teenagers are particularly vulnerable because their sense of financial consequence is not fully developed.”

Peer pressure sharpens the effect. In the lobbies of PUBG or Free Fire, skins and outfits are on display before the match even begins. The player with a rare costume or expensive weapon skin stands out, admired and respected. The one with default gear stands apart, marked as poor or inexperienced. For teenagers especially, the line between game and identity is thin. To be left out in the lobby feels like being left out in the classroom. Spending is not only about progress, it becomes a way to belong.

Mohib in Karachi admitted that not having skins felt like being invisible. “When I enter the PUBG lobby in default gear, people ignore me. If you have a rare skin, everyone wants to squad with you. It is not just a game, it decides your place with friends.”

Young players are the most vulnerable. They have little understanding of how real money turns into digital coins. A payment of a few hundred rupees may look harmless, but repeated often it adds up to thousands. Financial literacy comes late, long after the habit of buying has already taken root. For some children the pressure is doubled. They see friends showing off their new skins, they see timers running down, and they hear the in-game prompts urging them to buy. Saying no is harder than it looks.

The result is a system that feels like play but works like business. The designs are not accidents. They are built to keep players spending, to turn frustration into relief, and to blur the line between need and want. A chart of spending patterns by age shows the story clearly. Teenagers and young adults form the largest group of buyers, their behaviour shaped by impulse and by the desire to fit in. Older players may resist, but the younger ones rarely do.

The game promises entertainment, but beneath the bright screens and rewards is a careful structure of temptation. It begins with free entry and ends with a purchase that feels less like a choice and more like a requirement.

When parents say no

For many parents the first reaction to in-app purchases is to block them completely. They refuse to link their credit cards to app stores, they remove payment methods from the family phone, and they insist that free games must remain free. On the surface this looks like a simple solution. No card means no charge. But the reality is far more complicated. Children do not always stop when a barrier is placed in front of them. Instead they begin looking for other ways to get what the game demands.

In Pakistan, those other ways are never far away. Grey-market sellers openly advertise on online stores like Daraz, Facebook pages and WhatsApp groups, offering digital currency at discounted rates. All it takes is a message and an Easypaisa transfer, and the virtual coins arrive in the account within minutes. Parents may not even be aware these sellers exist, but for children they have become an alternative to using the family card. The risk is obvious. There are no receipts, no customer service, no guarantees. A child handing over money to an anonymous account online can just as easily lose it all to a scam.

Some situations are worse. Children desperate for digital currency sometimes turn to peer-to-peer trades. Strangers on the web exploit this need by promising the digital currency in exchange for pictures, dares, or favours that cross into dangerous territory. What begins as a game transaction can quickly turn into grooming or exploitation. A few cases shared quietly by parents describe children asked to record voice notes, share selfies, or perform actions on video in exchange for in-game currency. For a young player the line between fun and risk is blurred. The desire to keep playing makes them vulnerable to strangers who know exactly how to take advantage.

Even among friends, the risks are present. Children sometimes borrow each other’s accounts or ask older peers to make purchases on their behalf. This opens the door to stolen passwords, hacked accounts, and further manipulation. A child may think they are only borrowing an account for a short time but end up losing their progress and personal information in the process.

One mother in Lahore explained her fear clearly. “If I refuse to share my card details, my son will not just stop. He will go online looking for someone who promises in-game currency, and that person might trick him or mistreat him. I am more afraid of that than of the money leaving my account.” Her words capture the quiet dilemma many parents face. They know spending on games can get out of hand, but they also know that cutting it off entirely may push their children into more dangerous spaces.

This is the challenge. Saying no is not enough. The digital economy of games is too large, too easily accessible, and too tempting for children who have not yet learned caution. The better path is to guide them, to educate them on what is safe and what is not, and to give them a sense of responsibility over their spending. A strict wall of refusal may protect a bank account, but it cannot protect a child from the strangers waiting behind every glowing button and group chat link.

A growing debate

The question that has followed in-app purchases around the world is whether they are simply entertainment or whether they cross into something darker. At the centre of this debate are loot boxes. They look like gifts, crates or chests filled with the chance of a rare item, but opening them comes down to luck. Players may pay real money for the chance to win, yet they may walk away with nothing of value. The mechanics are so close to slot machines that regulators in several countries have begun to treat them as gambling.

In the United Kingdom, parliamentary committees have held hearings on the impact of loot boxes on children, pressing developers to disclose the odds of winning rare items. In Belgium and the Netherlands, regulators have gone further by banning certain forms of loot boxes entirely, ruling that they meet the definition of gambling under local laws. In the United States, senators have introduced bills that call for limits on in-app purchases in games targeted at children, and consumer groups have urged tech giants to introduce spending caps. The European Union has also moved towards a unified response, pushing for transparency and age safeguards.

Each of these steps reflects a growing recognition that the problem is not just about surprise bank charges, it is about fairness and protection. Children are often unable to understand the odds stacked against them. Parents are left with little recourse once the money is gone. Developers continue to argue that purchases are optional, yet the evidence of design pressures tells another story.

In Pakistan, the debate has not yet reached the same stage. There are no clear regulations on in-app spending, no requirements for companies to disclose odds, and no mechanisms for parents to challenge charges. The market operates in a grey area where global companies apply their own policies, but local consumers are left with little protection. While other countries are discussing gambling laws and consumer rights, here the conversation is only beginning in households where parents discover the true cost of a free download.

Consumer protection advocates argue that this gap needs to close. They point to the billions flowing through mobile wallets and app stores, and to the growing number of children drawn into games without understanding the consequences. Their call is not only for government oversight but also for corporate responsibility. Developers and payment platforms, they say, should build stronger safeguards, clearer warnings and stricter limits.

The debate will continue to grow as games expand and as digital currency becomes a part of everyday play. What began as questions in family living rooms has reached courtrooms and parliaments abroad. Without action in Pakistan, the risks remain in the hands of parents who are left to navigate them alone.

More than just a game

The blue button still waits at the corner of the screen, glowing softly, offering the same promise it always does. For the child playing it is the bridge between frustration and progress, between being left out and fitting in. For the parent standing in the background it is the reminder that nothing in the game is truly free.

What began as play has turned into a cycle of choice and pressure, where entertainment blends with business and innocence meets the reality of money. The design of these games is clever enough to make the purchase feel harmless, yet powerful enough to shape behaviour. A hundred rupees today, another tomorrow, until the habit is formed. The button is never only about coins or skins. It is about belonging, identity, and the fear of being left behind.

The question that lingers is whether this is still entertainment or whether it has slipped into exploitation. A game that once promised escape now carries the weight of bills, scams, and the risk of strangers who prey on young players. The solution cannot be to end all play, nor can it be to give in to every glowing offer. It lies somewhere in the difficult space between.

Parents will need to guide rather than ban, to teach rather than forbid. Children will need to learn that value exists beyond the skins on a screen. And perhaps the industry itself must decide whether it wants to be remembered for the joy of play, or for the price it placed on every moment of it.