The 2025 Asia Cup will be remembered not for the hundreds scored or wickets taken, but for the handshakes that didn’t happen, the gestures that sparked outrage, and the trophy that was never lifted on stage. Cricket, which should have been the only headline, ended up sharing space with drama that kept spilling over from the press rooms to the field and finally to the podium.

For Pakistan, the build-up carried hope. The squad looked balanced, there was a belief that this time the side could finally go all the way. And in parts, they did live up to that expectation, brushing past Oman, holding their nerves against Sri Lanka and Bangladesh, and doing just enough to book a place in the final. But while the runs and wickets came, it was something else that began to define their journey.

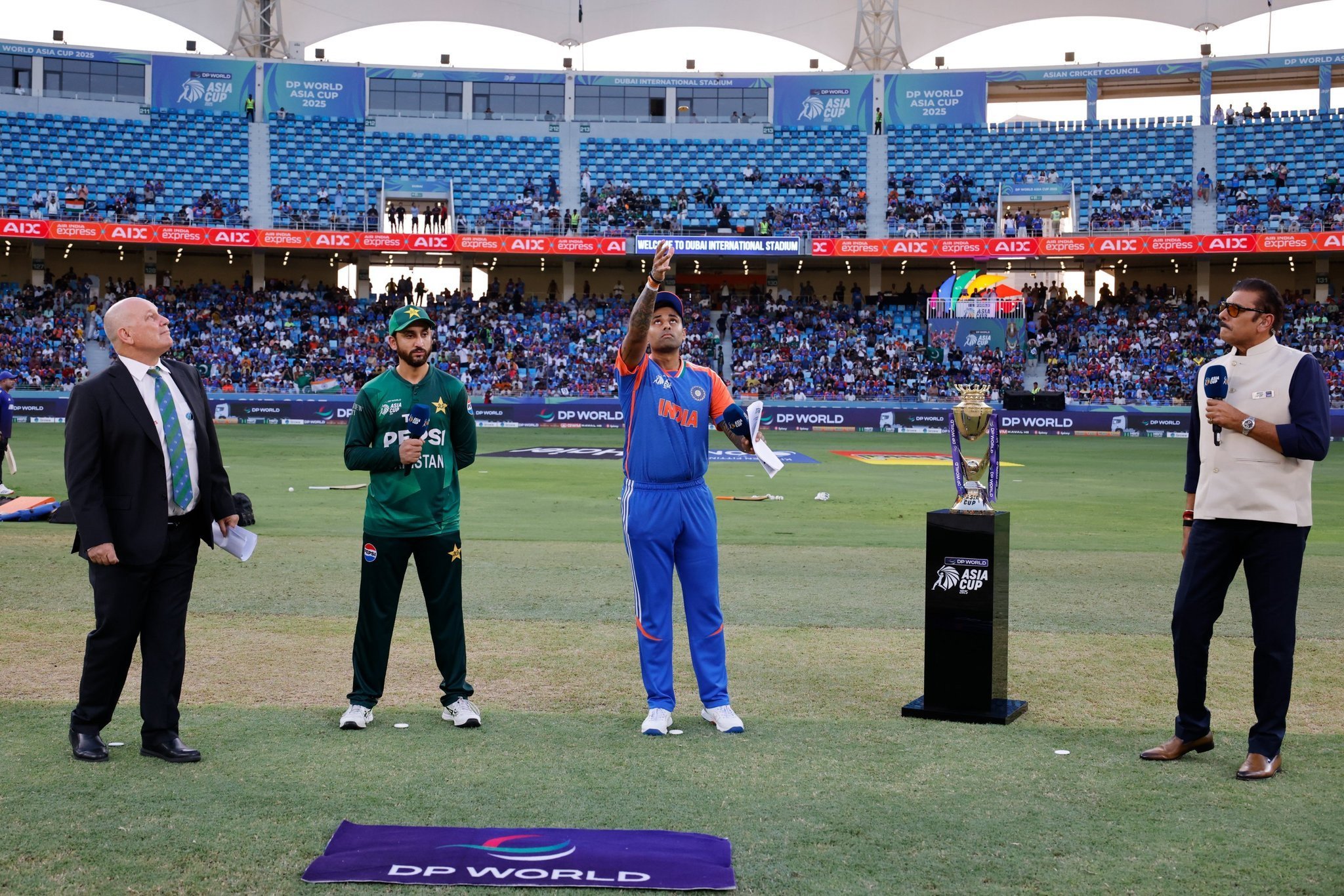

The spark came before the tournament had even started. At the captains’ press conference, India’s skipper shook hands with PCB Chief and ACC President Mohsin Naqvi and Pakistan’s captain Salman Ali Agha. What should have been no more than a polite gesture quickly snowballed. Indian fans and media saw it as a political signal, and suddenly the focus had shifted. From then on, every Pakistan game, especially against India, seemed to carry a weight heavier than cricket.

India, after their first victory over Pakistan, even went as far as to say there was no competition, dismissing Pakistan as not even a par team and calling Afghanistan the second-best in Asia. But what followed told a different story: Afghanistan were knocked out in the group stage, while Pakistan fought their way to the final and gave India a far tougher contest than those early claims suggested.

By the time the final ended with Pakistan’s collapse and India’s “invisible trophy” celebration, it felt like the cricket itself had been reduced to background noise. The Asia Cup had turned into a stage where symbolism and provocation mattered as much as the scorecard, and Pakistan were left caught between the two.

The spark before the first ball

On a lighter note, it almost looked symbolic that Pakistan and India needed Afghanistan to sit between them. At the captains’ press conference in Dubai, Rashid Khan found himself sandwiched in the middle seat, looking more awkward than amused as the two biggest rivals in the game avoided even a casual glance at each other. When a reporter threw the inevitable question about aggression on the field, both captains gave their answers without turning their heads, speaking into the mic and then sliding it across the table without eye contact. Rashid, caught in the middle, shifted in his chair with a nervous smile, unsure if he should laugh or just look down.

It was a scene that summed up the mood, tense, theatrical, and in many ways bigger than the cricket that was yet to come. But what really set things off came at the end of that same press conference. India’s Suryakumar Yadav, who was standing in as captain, shook hands with Agha and Naqvi. What might have been just another polite gesture in any other tournament quickly turned into a storm.

Back home in India, fans and media outlets erupted. For them, the handshake with Naqvi, who also holds a political office as Interior Minister, was no ordinary courtesy. It was painted as a sign of weakness, even betrayal. TV panels debated it, hashtags trended, and suddenly the focus of the Asia Cup had shifted before a single ball was bowled.

From that day on, the rivalry wasn’t just about cricket. Every toss, every gesture, and every exchange carried the shadow of that press conference, and the tournament had already taken on a very different tone.

A strong start, rising hopes

Pakistan’s campaign began the way fans would have wanted, simple, clinical, and without much fuss. Against Oman, there was never really a contest. The batters scored freely, the bowlers looked sharp, and the result was a walkover. It was the kind of win that doesn’t say too much but does enough to calm early nerves.

The next game, against UAE, was a bit tighter. Pakistan had to work harder, but even then the control was there. The middle order chipped in, the spinners tied things up, and the finish came without drama. By that point, the path looked clear: this was a side good enough to get to the final. Fans back home started to whisper about redemption, about finally seeing their team lift an Asia Cup in front of India. The mood was slowly building, every win was another reason to believe.

But the cricket was only half the story. Away from the pitch, the noise refused to settle. The press conference handshake still followed the team everywhere they went. Reporters kept circling back to it in post-match questions. Indian channels replayed it on loop, and social media treated it like a scandal bigger than the cricket itself. Even when Pakistan won, the conversation quickly drifted to politics and gestures instead of partnerships and bowling spells.

So, while the start was strong and steady, it already felt like the team was carrying more than just their own expectations. The cricket was convincing, yes, but the storm outside the boundary rope was beginning to gather.

The rivalry matches: Fuel to the fire

When Pakistan finally met India on the field, the cricket itself almost felt secondary. The first clash ended in a defeat for Pakistan, but what stole the headlines was what happened before the first ball. At the toss and again after the match, the usual handshake was skipped. It looked awkward on live television, but quickly turned into something bigger. For Indian media, it was Pakistan showing disrespect. For Pakistani fans, it was India refusing to uphold basic sportsmanship. By the next morning, the result of the match was hardly being discussed, the conversation was all about who refused whose hand.

Things escalated further in the Super Four stage. Haris Rauf, fielding near the boundary, celebrated a moment by stretching out his arms in a “jet crashing” motion and showing 6-0. Clips went viral instantly, with Indian commentators linking it to war symbolism. When hauled up, Haris shot back with a counter-question to the match referee during the hearing: “What do you think this sign even means?” It was his way of deflecting, but the storm had already gathered.

In the same match, Sahibzada Farhan reached his fifty and marked it with a rifle-firing gesture. The BCCI wasted no time in filing an official complaint with the ICC, calling it a violation of the code of conduct. Pakistani fans, however, dug up old clips of Indian players making similar gun-shooting celebrations in past matches. Screenshots and videos flooded timelines, the argument quickly turning into a social media battleground where every side tried to prove hypocrisy in the other.

By this point, the cricket itself was being drowned out. Pakistan had suffered another loss to India, but the bigger narrative was now fixed: one side portrayed as aggressive to the point of provocation, the other as standing its ground with defiance. The rivalry, already the most charged in world cricket, had turned into a rolling controversy machine. Every run, every wicket, and every gesture seemed to carry a double meaning.

And while fans back home hoped the team would stay focused on the cricket, the noise online suggested otherwise. The Asia Cup was no longer just a tournament, it was turning into theatre.

When controversy became the story

By the middle of the tournament, the cricket had slipped firmly into second place. What dominated headlines were the little side-shows that refused to go away. The most bizarre of them came during Pakistan’s game against UAE, when the organizers mistakenly played a snippet of the pop song “Jalebi Baby” instead of the national anthem. For a few seconds, players stood confused, and fans were left furious. The clip went viral in minutes, not for the cricket that followed, but for the anthem fiasco that felt like another insult.

At the same time, the handshake drama kept circling back. Tosses, post-match presentations, even warm-up routines were suddenly under scrutiny. People tuned in not to hear who won the toss but to check whether the captains would shake hands or turn away. Every shrug, every glance, or lack of it, became part of the story. It had turned into a theatre of gestures, where the smallest act was dissected far more than a good spell of bowling.

The PCB also found itself in the middle of the storm. Officials lodged protests over how refereeing decisions were being handled, particularly after the Rauf and Farhan incidents. Match referee Andy Pycroft stayed on despite Pakistan’s formal objections, adding fuel to a belief that the system was stacked against them. And then there was Naqvi. His dual role as PCB chief and Interior Minister made him a lightning rod for criticism. In India, his presence at every game was painted as politics creeping into cricket. In Pakistan, his supporters framed it as standing tall in the face of pressure.

With every passing match, the game itself seemed to fade into the background. Pakistan’s wins over Sri Lanka and Bangladesh were solid cricketing performances, but nobody was really talking about strike rates or bowling figures. Instead, the focus stayed on handshakes, anthem mishaps, and who said what in press rooms.

By then, the Asia Cup had stopped feeling like a tournament and more like an extended drama series. Cricket was still being played, but the storylines that mattered most were happening off the ball.

The final and Its fallout

For a brief moment in the final, it looked like Pakistan had found their rhythm. The openers started with intent, runs came quickly, and there was hope of putting up a score that could test India. But then the collapse began. Nine wickets fell for just 33 runs, and what should have been a competitive total turned into a modest 146. With the way India had been batting all tournament, it never felt like enough. Tilak Varma’s calm 69 anchored the chase, and India crossed the line with a steady hand, leaving Pakistan with nothing but what-ifs.

But as had become the theme of the Asia Cup, the cricket itself was soon forgotten. The aftermath of the final stole the spotlight in a way that few could have imagined. From the very beginning, the Indian camp had treated this tournament as an extension of the political tensions from the war that ended months earlier. The decision not to accept the trophy from Naqvi, who stood on stage in his role as ACC president but Indian players and management show his as standing with three roles – PCB Chief, ACC President and most importantly Interior Minister of Pakistan, was the final act of that stance. The presentation was cut short, the ceremony looked hollow, and the images went around the world without a trophy ever being lifted.

What followed was almost surreal. The Indian players staged their own celebration, posing with an “invisible trophy,” smiling and laughing as if mocking both the organizers and Pakistan. And then came a moment that hurt Pakistan just as much. Captain Salman Ali Agha, handed the runners-up cheque, tossed it onto the podium floor in frustration. It was a gesture that many saw as beneath the occasion, if he felt that strongly, critics argued, he should have refused it outright instead of accepting it and discarding it.

The drama carried into the post-match press conference. Indian players smiled through questions, defended their actions, and even laughed when asked why they had turned cricket into a political battlefield. When a Pakistani journalist pressed the point, the Indian camp simply avoided the question. It was the perfect closing scene for a tournament where sportsmanship had repeatedly taken a back seat.

Looking back, the Asia Cup never really felt like a cricket tournament. It played out more like a string of provocations stitched together by a few matches in between. For Pakistan, reaching the final was still an achievement, a sign that the team had enough talent and fight to be in the mix until the very end. But it also became a cautionary tale, proof of how quickly focus can shift from the scoreboard to the sidelines.

In the end, the story of Pakistan’s Asia Cup was not written in centuries or five-wicket hauls. It was written in handshakes that caused uproar, gestures that sparked complaints, and silences that carried more weight than words. And that, perhaps, said more than cricket ever could.