As the campaign for immunisation against HPV began, a lot of objections to the vaccine came to the fore, raising doubts in the minds of even those optimistic people who usually see the bright side of things. The most common objection is why a girl as young as nine years old needs to be vaccinated against a disease that, in her opinion, usually affects older women.

For those who question the logic behind early vaccination and its efficacy and need, let me present some facts regarding the vaccine and why it is important.

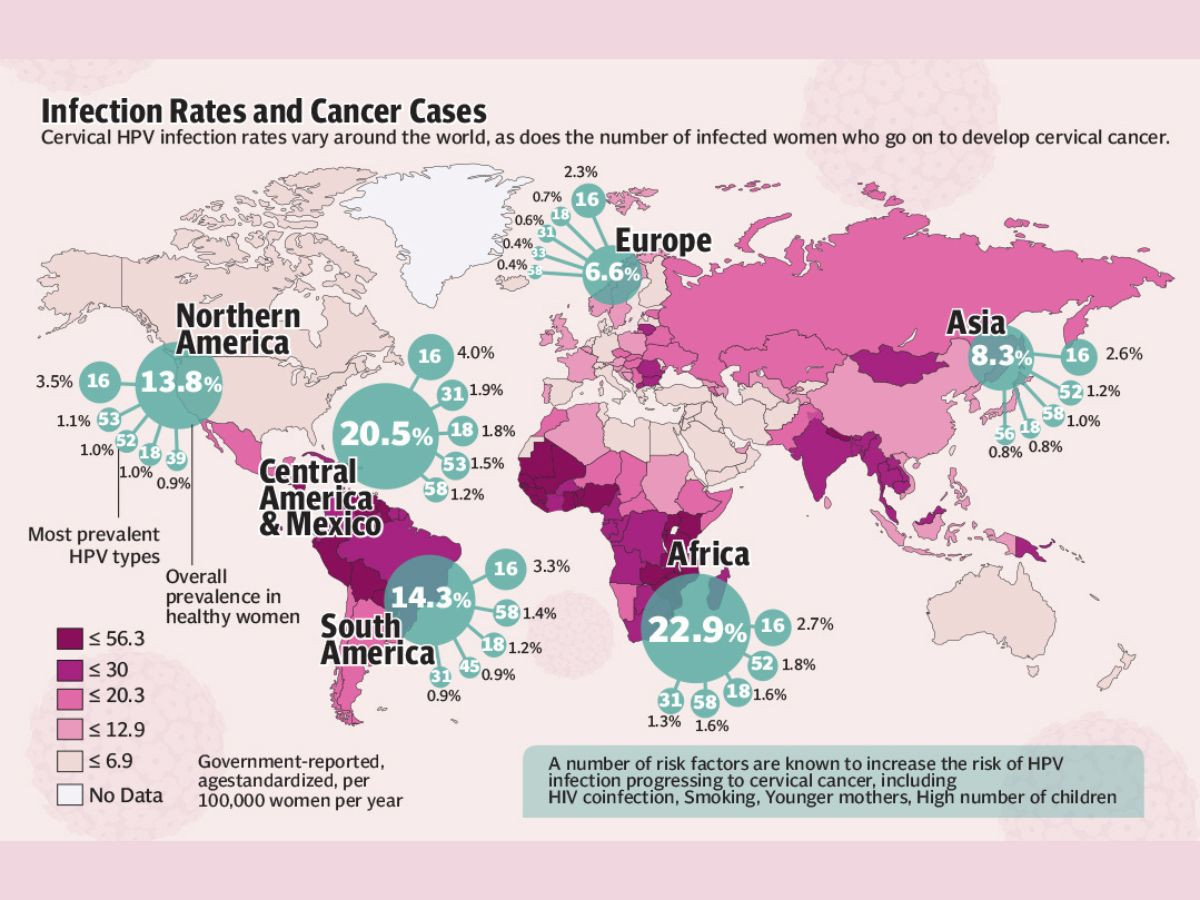

HPV vaccine prevents cervical cancer, which, though is preventable and treatable if diagnosed at an early stage, silently claims thousands of lives each year. Globally, cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer in women, accounting for around 660,000 new cases in 2022. In the same year, about 94 percent of the 350,000 deaths caused by cervical cancer occurred in low- and middle-income countries.

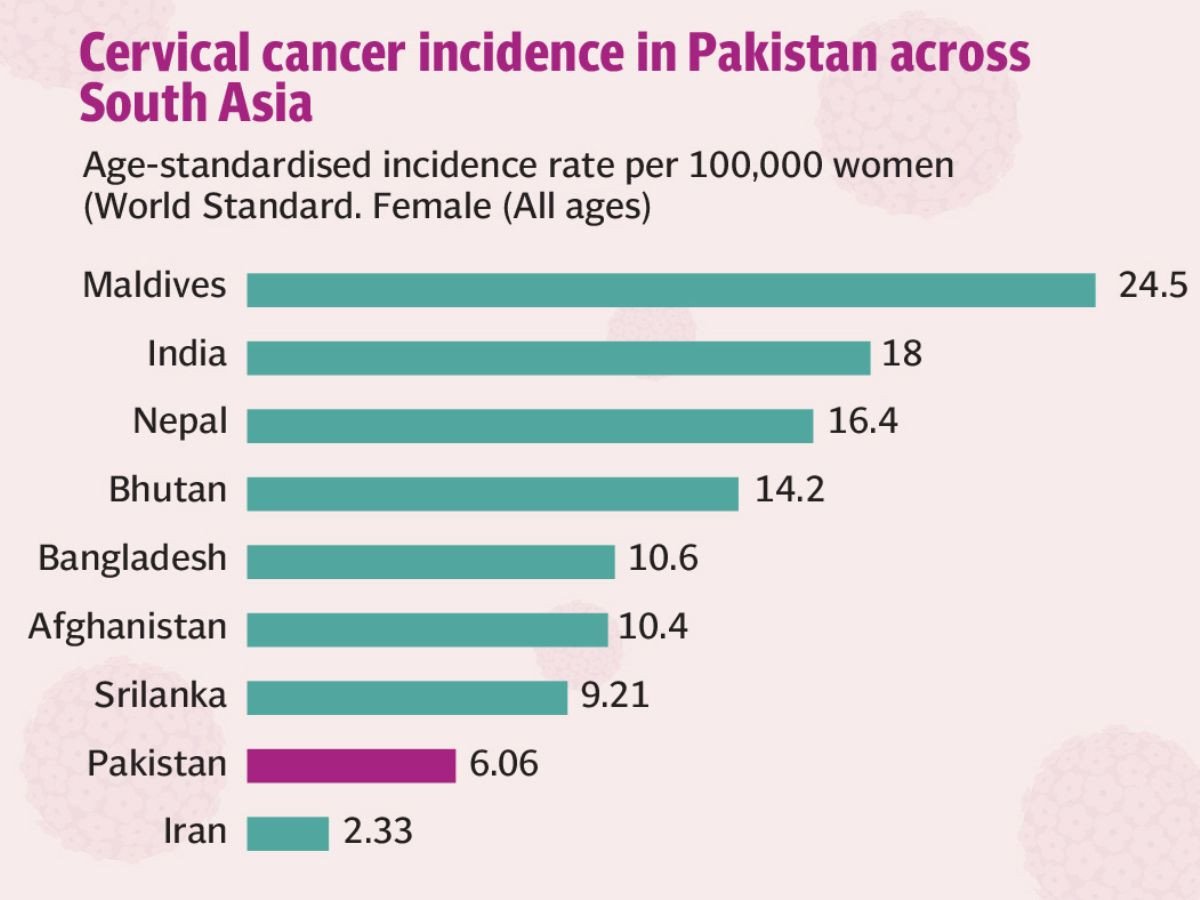

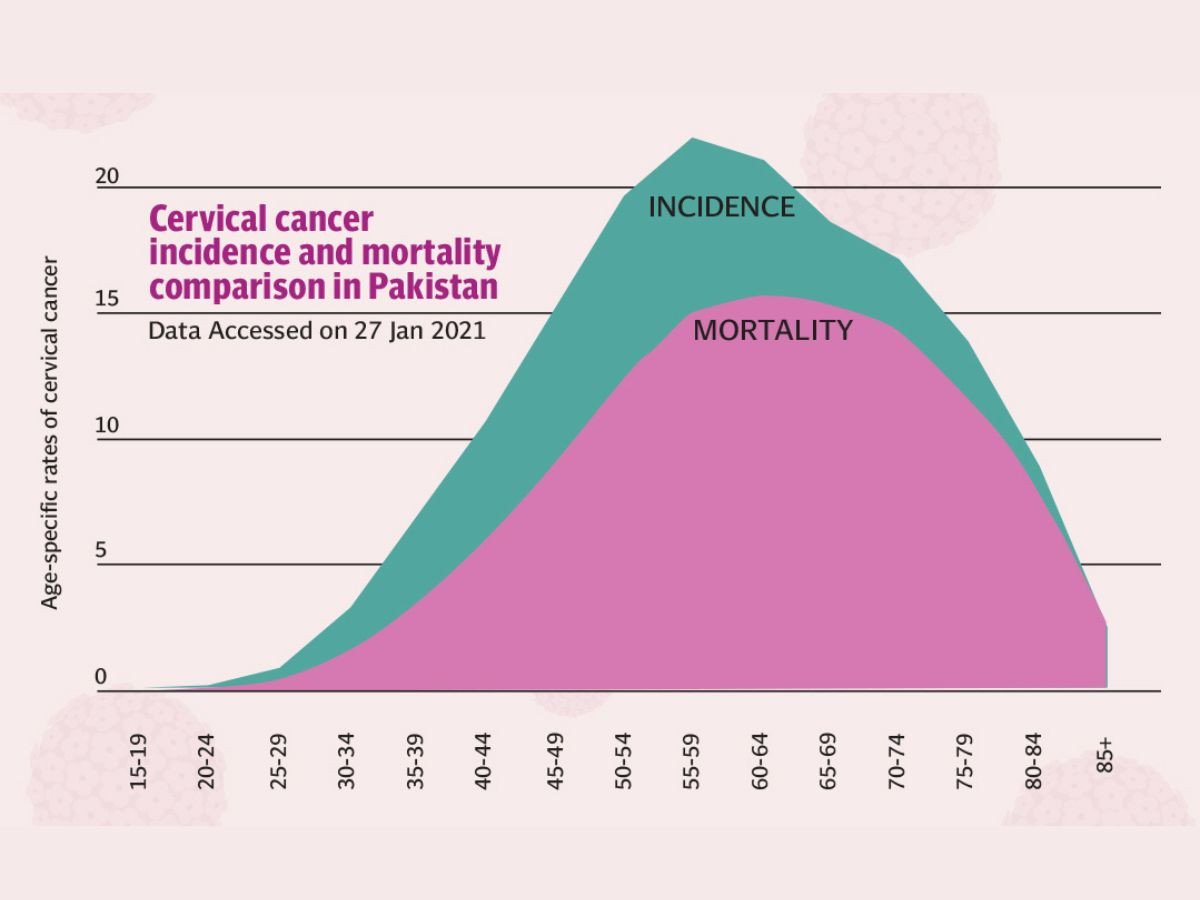

Cervical cancer is the third most prevalent cancer among women in Pakistan. With a female population of 73.8 million aged 15 years and older at risk, over 5,000 women are diagnosed annually, many at advanced stages when treatment options are limited and outcomes are poor. Almost 3,200 of them (64%) die from the disease. The mortality rate, one of the highest in South Asia, is primarily attributed to delayed diagnoses and limited access to screening programmes. Despite this, Pakistan remains dangerously behind in protecting its girls and women, though globally there are examples of success in reducing cervical cancer occurrence due to timely vaccination and treatment when detected early.

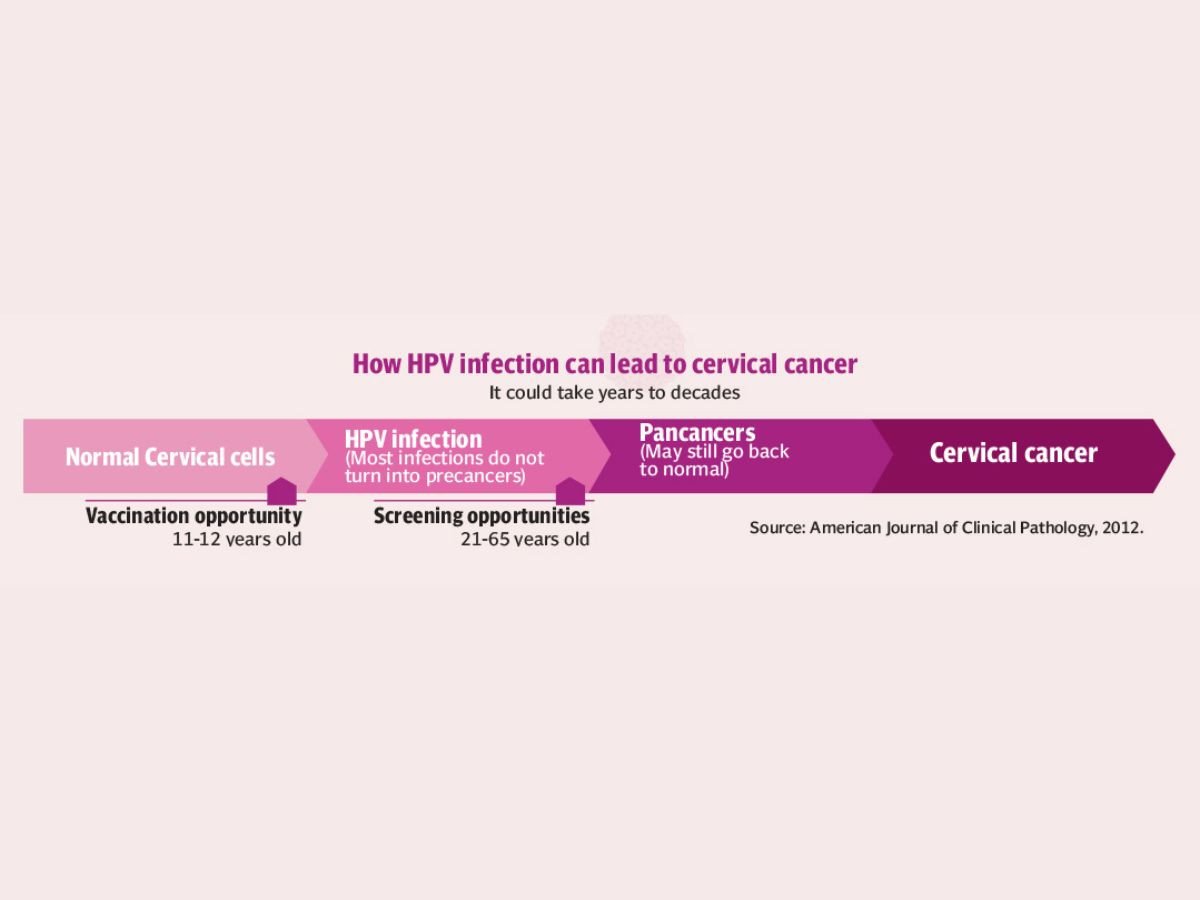

Cervical cancer is mostly caused by a common virus called human papillomavirus (HPV) that is primarily transmitted through sexual contact. HPV infection is widespread and while many strains of HPV are harmless, high-risk types, particularly HPV 16 and 18, are responsible for nearly all cases of cervical cancer. In most people, the virus does not cause any problems and goes away on its own; however, in some cases it can cause changes in the cells that may lead to cancer.

While cervical cancer is caused by the virus there are several factors that increase the risk of developing cancer. “When the immune system is compromised, a high risk HPV infection is more likely to persist and lead to abnormal cervical cell changes. Multiple pregnancies as hormonal changes during pregnancy may make a woman more susceptible to HPV virus, early sexual activity, and poor diet,” Samrina Hashmi, Consultant Obstetrician and Gynaecologist and Fertility specialist, Noor Hospital and Concept Fertility, Karachi, explained the risk factors.

Whether someone not sexually active can have cervical cancer, Dr Hashmi said, “Because nearly all cases of cervical cancer result from an individual having a high risk strain of HPV, it is highly unlikely for someone to develop cervical cancer if they have never had sex. But in medicine we never say never.”

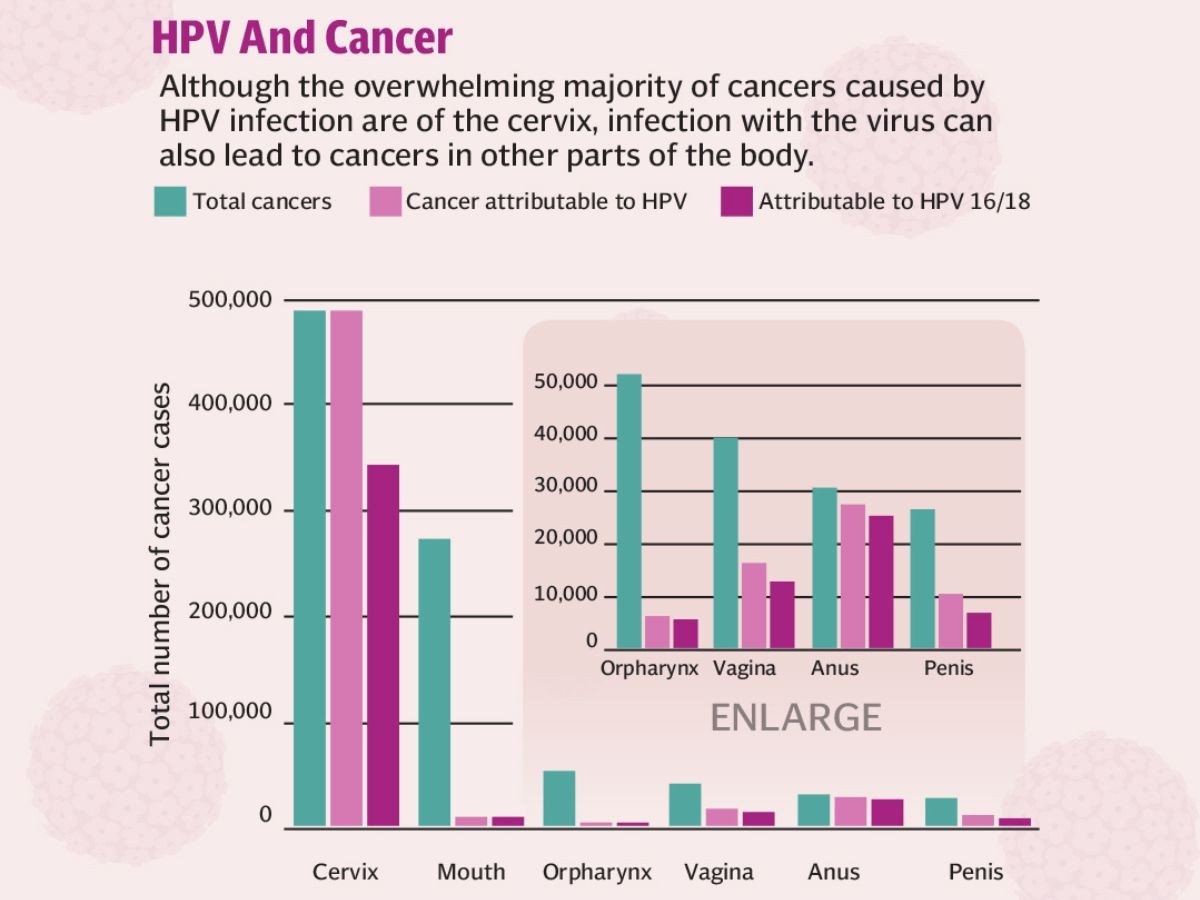

While cervical cancer remains the most recognised HPV-related malignancy, the virus is also linked to cancers of other sexual organs, mouth and throat.

Since cervical cancer can be cured if diagnosed and treated at an early stage, recognising symptoms and seeking medical advice is crucial. Initially, there might not be any symptoms but as it grows, it might cause symptoms such as menstrual bleeding that is heavier and lasts longer than usual; bleeding between periods, after menopause, or after intercourse; watery, bloody vaginal discharge that may be heavy and have a foul odour; persistent pain in the back, legs, or pelvis; weight loss, fatigue and loss of appetite; vaginal discomfort; swelling in the legs.

However, the good news is that it is possible to reduce your risk of cervical cancer and the best way is to receive HPV vaccine.

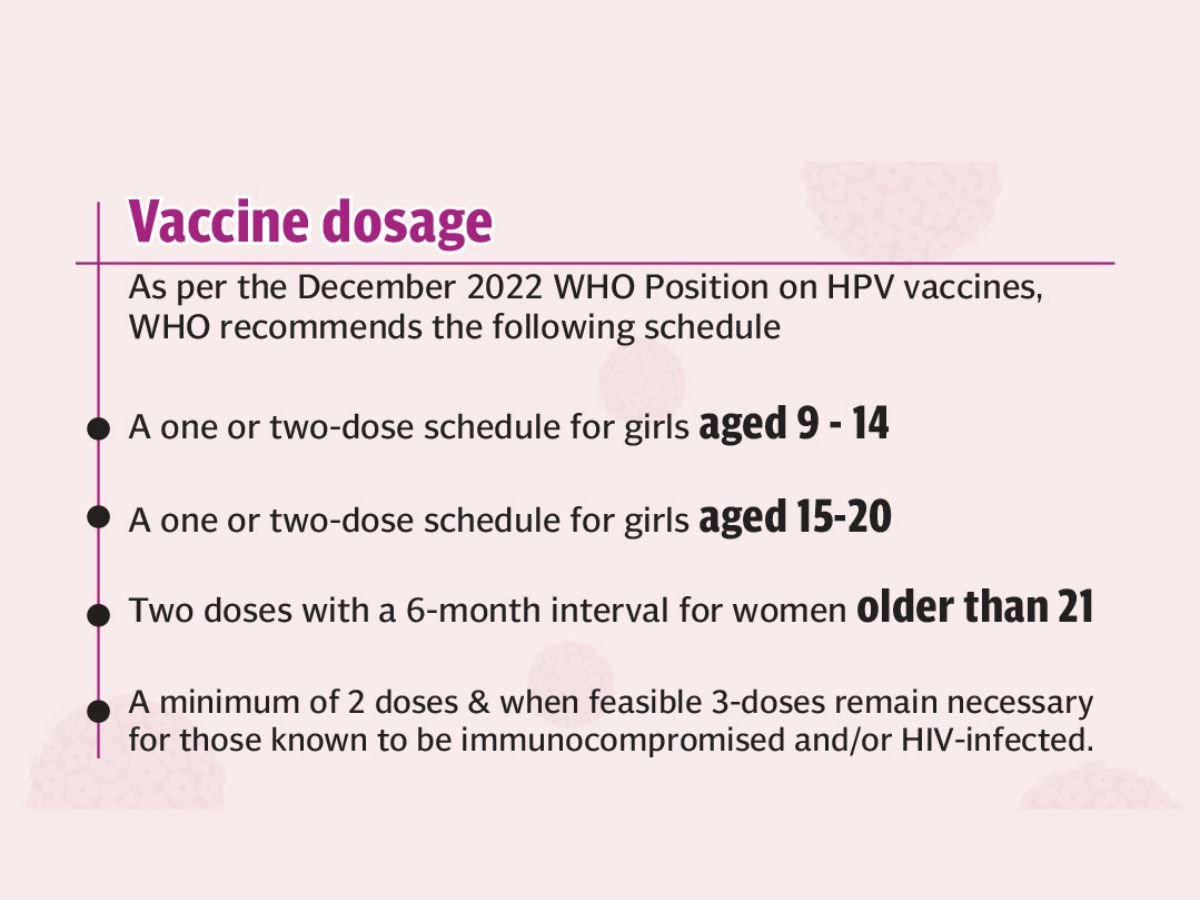

HPV vaccine is recommended for everyone through age 26. It is recommended that HPV vaccines should be given to all girls between ages nine and 14 years, before exposure to the virus or, to say, before having the first sexual contact because younger people respond better to the vaccine than older people do. Two doses are sufficient for most children in this age group, while three are recommended for those with compromised immunity or for individuals above 15 years of age. The doses are given at least five months apart. Individuals who begin the vaccine series at ages 15 through 26 should get three doses of the vaccine.

“Many people in this older age group have already been exposed to the virus, diminishing the vaccine’s benefit,” says Dr Hashmi. Also, “It should be kept in mind that HPV vaccine prevents new HPV infection but does not treat existing HPV infections or diseases. It works best when given at a younger age before any exposure to HPV. Once someone has been infected with HPV, the vaccine might not work as well or at all. If given before someone has HPV infection, the vaccine can prevent most cervical cancers,” says Dr Hashmi.

The current HPV vaccines target the main high-risk virus types but cannot cover all cancer-causing strains, or treat existing infections. In addition, though in rare cases, cervical cancer can also be caused without HPV infection, women aged 25 to 64 are advised to have cervical screening every five years, even after vaccination.

Also because there are no symptoms in the early stage of cervical it is important to have regular screening tests. Women ages 21 to 29 who have not been vaccinated should have a Pap ( Papanicolaou , named after Greek physician) test that can find changes in the cervix that might lead to cancer, every three years

To protect millions of adolescent girls, i.e. its future generation, the Pakistan government has introduced the HPV vaccine in partnership with UNICEF, GAVI the vaccine alliance, and the World Health Organisation. The first HPV vaccination campaign that ran from September 15–27 aimed to cover 15 million girls aged 9-14; the campaign was conducted at fixed centres, outreach sites and schools, and through mobile/special vaccination teams. Later, the vaccine would be available at government facilities and will be incorporated in the routine immunisation schedule.

Despite the fact that it is a very timely intervention and is being promoted through media in a very efficient manner, as in the past with polio vaccine and Covid-19 vaccine, a number of myths have arisen regarding the HPV vaccine that have sown seeds of doubt among parents. Myths vary from vaccines causing infertility, to children being sexually inactive so why vaccinate them against something that does not concern them at this age, to HPV vaccines being new and hence no safety and efficacy data available on the long-tern side effects.

These myths, that been thoroughly debunked by science, are driven by stigma and misinformation and are barriers to HPV vaccine acceptance in Pakistan.

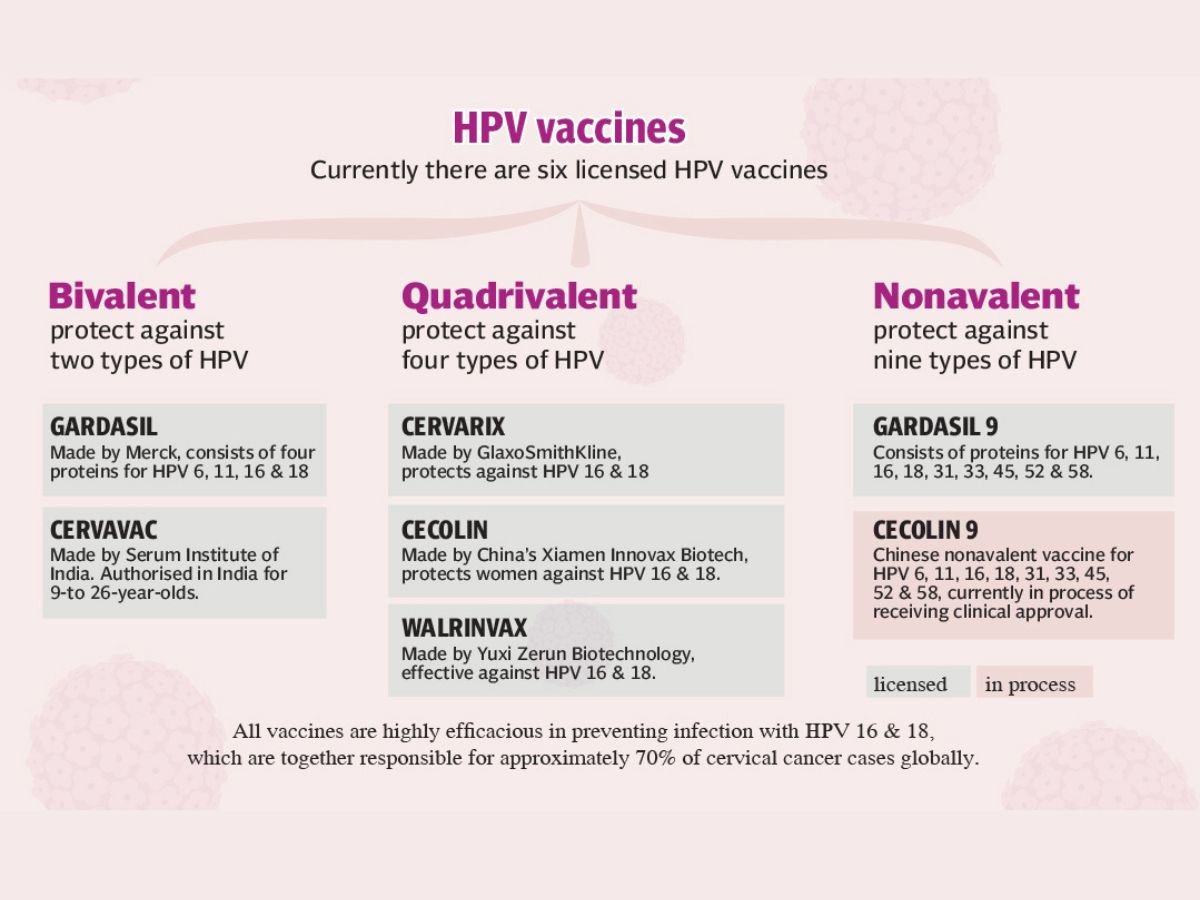

It is being said that the vaccine is new and there’s no safety and efficacy data on long term side effects. The fact is that the HPV vaccine which protects against the high-risk HPV types 16 and 18, and have shown to be safe and effective in preventing HPV infection and cervical cancer, was developed in the early 2000s. The World Health Organisation (WHO), the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and numerous global studies have confirmed the vaccine’s safety and effectiveness. Millions of doses have been administered worldwide.

Its widespread introduction into national programmes began in mid-to-late 2000s, and by 2023, its access expanded to 150 countries. The World Health Organisation has set a target of fully vaccinating 90 percent of girls by age 15 by 2030. At present, only about 48 percent of girls worldwide are fully vaccinated.

The efficacy of the vaccine is evident in the fact that the countries that introduced the HPV vaccine have seen dramatic declines in infection rates and prevalence of cervical cancer. For example, Australia is on track to eliminate cervical cancer within a decade, while Rwanda, a low-income country, has achieved over 90 percent coverage.

Regarding the doubt that the vaccine causes infertility, Dr Hashmi gave two examples of studies that prove otherwise: “An evaluation in 2018 of nearly 20,000 women aged 11–34 years found no connection between adolescent vaccination and ovarian failure. Recent data from Denmark also showed no association between HPV and primary ovarian insufficiency among 950,000 Danish women and girls.”

Another objection is that children are not sexually active so why vaccinate them against something that does not concern them at this age. “Adolescents vaccinated under the age of 15 years showed much higher HPV antibody than older peers,” Dr Hashmi explains. “They had a higher immune response. This together with the results of clinical trials showing persistent high antibody titres after receiving two doses of HPV vaccination at younger age led to the recommendation of two doses in adolescents under the ages of 15 years.”

To address religious and cultural concerns and promote greater acceptance, a multifaceted approach is essential. It is important to present the HPV vaccine as ‘a protective measure against cervical cancer’ which affects thousands of women annually and not as a means of protection against a sexually transmitted infection. Religious scholars in several Muslim countries have reviewed and approved the HPV vaccine. For instance, in Malaysia, a Muslim-majority nation, the vaccine was successfully integrated into the national immunisation programme; for greater acceptance it was presented as a cancer prevention measure, which definitely helped.

The same approach can be adopted in Pakistan for greater acceptance. Public health messaging should carefully avoid sexual references, as these can alienate certain segments of the population.

To address these misconceptions and enhance acceptance, it is important to engage trusted members of the community such as religious leaders, teachers, health workers and influencers. As people trust them they can use their influence to cultivate confidence among the people and work to dismantle the myths surrounding the vaccine and encourage people to have their children vaccinated.

HPV vaccine: myths & facts

The human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine has been around for more than a decade! The vaccine is safe, effective, and protects against many strains of HPV, which is the most common sexually transmitted infection and a cause of several cancers. Despite numerous benefits, several misconceptions about the vaccine still persist.

1. MYTH: HPV vaccination is not safe.

FACT: The HPV vaccine is safe and doesn’t contribute to any serious health issues. Like any vaccine or medicine, the vaccine may cause mild reactions. The most common are pain or redness in the arm where the shot is given. Other typical side effects include low-grade fever, headache or feeling tired, nausea, or muscle or joint pain – all of which are temporary. Rarely, an allergic reaction can occur, and individuals should not get the vaccine if they are allergic to any of the components.

The vaccine itself has been researched for many years (including at least 10 years of research before it could even be used in humans) and is highly monitored by the Food and Drug Administration. Vaccinations in the U.S. have never been safer because of the stringent standards the FDA uses.

2. MYTH: HPV vaccination can lead to infertility.

FACT: Claims of HPV vaccine-induced infertility due to premature ovarian failure are anecdotal and not backed by research or clinical trials. A recent study of over 200,000 women found no association between the HPV vaccine and premature ovarian failure.1 In fact, the HPV vaccine can actually help protect fertility by preventing gynecological problems related to the treatment of cervical cancer. It’s possible that the treatment of cervical cancer could leave a woman unable to have children. It’s also possible that treatment for cervical pre-cancer could put a woman at risk for problems with her cervix, which could cause preterm delivery or other complications.

3. MYTH: HPV vaccination is not effective at preventing cervical cancer.

FACT: In the studies that led to the approval of HPV vaccines, the vaccines provided nearly 100% protection against persistent cervical infections with HPV types 16 and 18, plus the pre-cancers that those persistent infections can cause. In addition, a clinical trial of HPV vaccines in men indicated that they can prevent anal cell changes caused by persistent infection and genital warts.2 HPV-associated cancers can take decades to develop, so it will be a few more years before we will be able to have studies comparing cancer rates. Advanced pre-cancers have long been universally accepted markers for cancer.

4. MYTH: Only girls need to get the HPV vaccine, men and boys don’t need it.

FACT: HPV affects both men and women. It can cause genital warts, penile, anal, and oral cancer in men. It can also be easily transmitted to a sex partner without either of the partners knowing.

5. MYTH: Getting the HPV vaccine will encourage adolescents to be more sexually promiscuous.

FACT: No research links the HPV vaccine to increases in sexual activity. No evidence giving the HPV vaccine is linked with higher sexual activity. In fact, a recent article reviewing studies of over 500,000 individuals revealed that there was no increase in sexual activity after HPV vaccination.3 In fact, vaccinated participants actually engaged in safer sexual practices than unvaccinated participants! Also, adolescents who get the vaccine don’t have more partners after they become sexually active.4

6. MYTH: The HPV vaccine doesn’t protect against enough strains of human papillomavirus to be worth getting.

FACT: The current HPV vaccination protects against nine types of HPV. These nine have been linked to more than 90 percent of genital warts cases, 90 percent of cervical cancers, and 70 percent of anal cancer diagnoses. This vaccination is highly protective to prevent this very common viral infection and to help prevent genital warts and cancers.

7. MYTH: HPV is uncommon, and it’s unlikely I’ll be infected, so there’s no need to get the HPV vaccine.

FACT: The genital HPV infection is the most common sexually transmitted infection and there are over 14 million new infections each year in the United States. It’s so common that nearly every male and female will be infected with at least one type of HPV at least once in their lifetime. Currently, over 80 million Americans are infected.

Rizwana Naqvi is a freelance journalist and tweets @naqviriz; she can be reached at naqvi59rizwana@gmail.com

All facts and information is the sole responsibility of the writer