In Pakistan, heat is no longer something you brace for every summer, it’s something you endure. Day after day. Jacobabad has touched 50 degrees Celsius more than once, turning public buses into slow-moving ovens and rooftops into frying pans. The air in cities like Lahore and Karachi feels thicker than ever. Climate change isn’t coming. It’s already here. Every summer, the signs are harder to ignore.

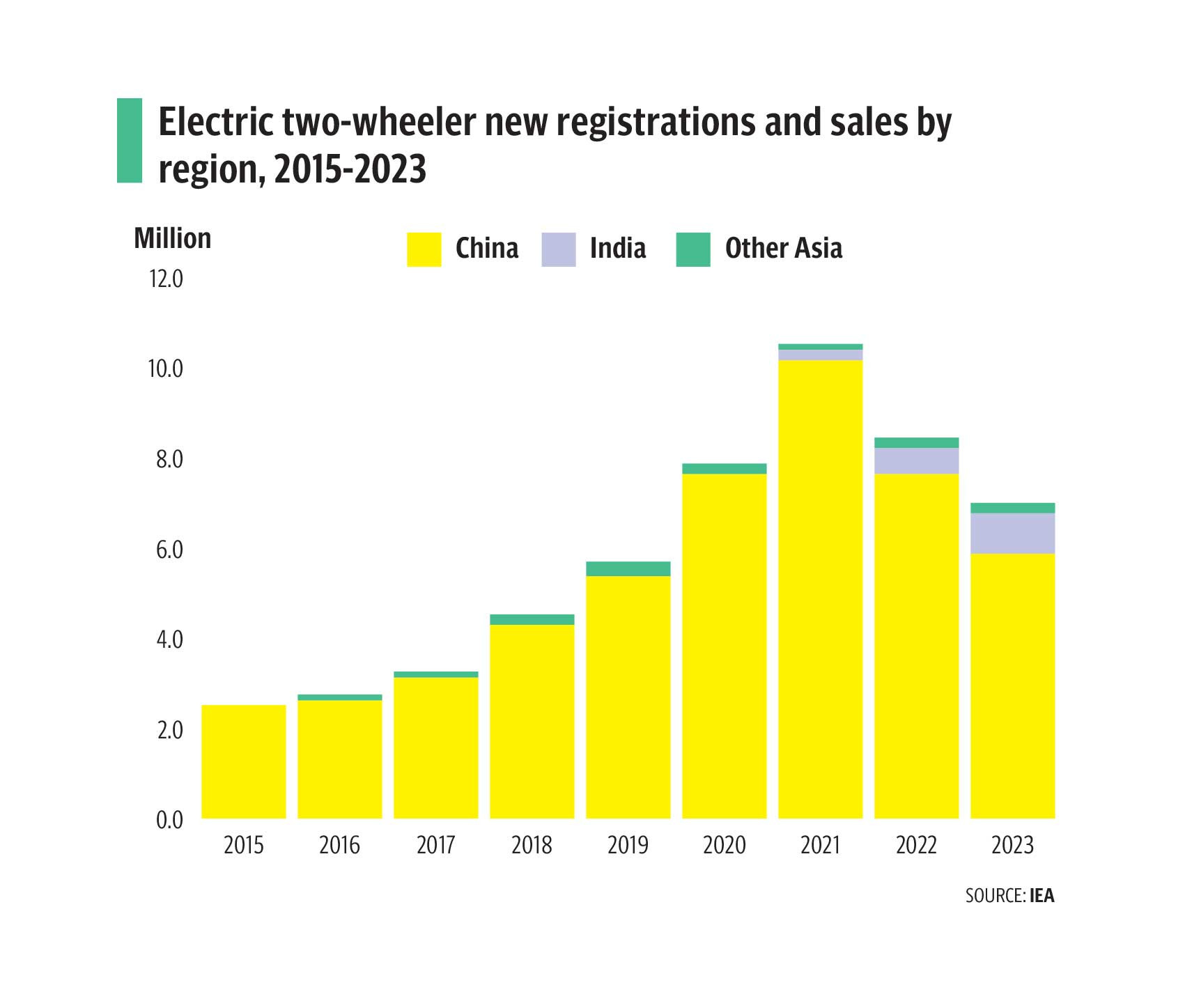

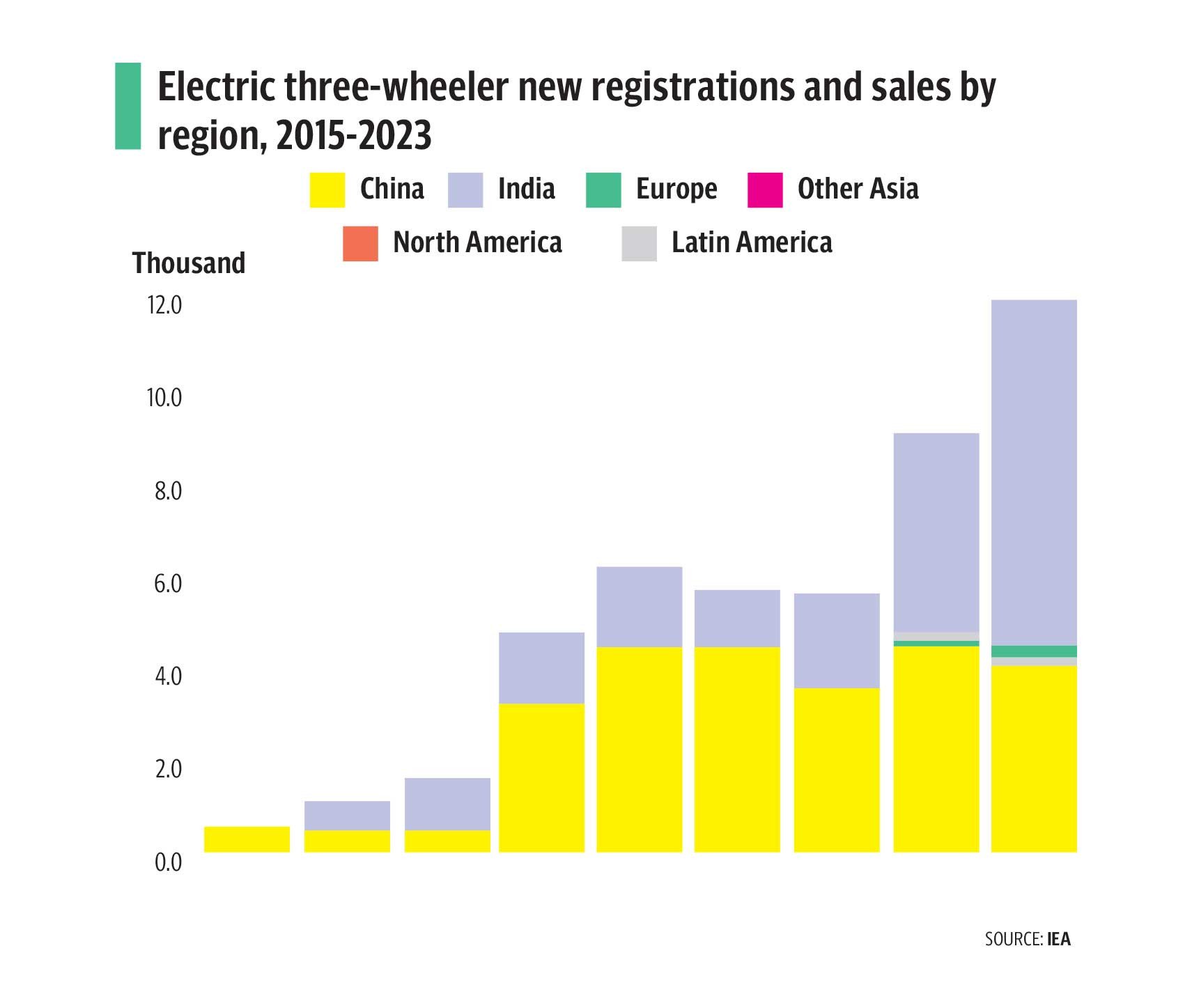

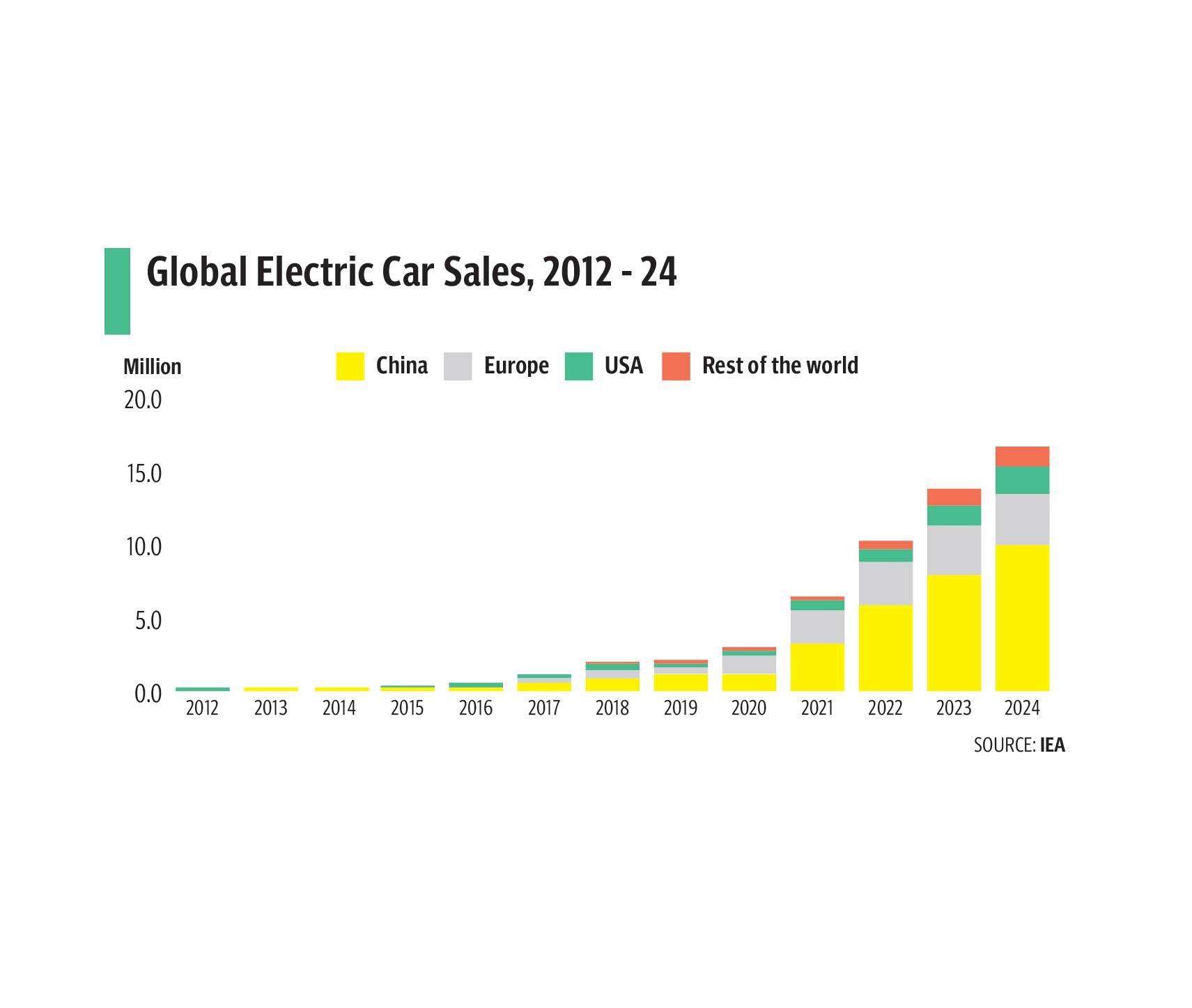

Around the world, one of the first sectors forced to change has been transportation. The electric vehicle (EV) movement is growing, fast. From private cars and delivery bikes to buses and e-rickshaws, the shift from petrol to plug-in is no longer an experiment. It’s a necessity.

Pakistan isn’t sprinting in this race, but it’s not standing still either. The shift is slow, uneven, and often tangled in bureaucracy, but it has begun. From federal policy briefs to small-scale pilot projects, from ride-hailing fleets to budget EV bikes, the effort to reduce the country’s dependence on imported fuel is picking up speed. And it’s not just about cost anymore, it’s about survival.

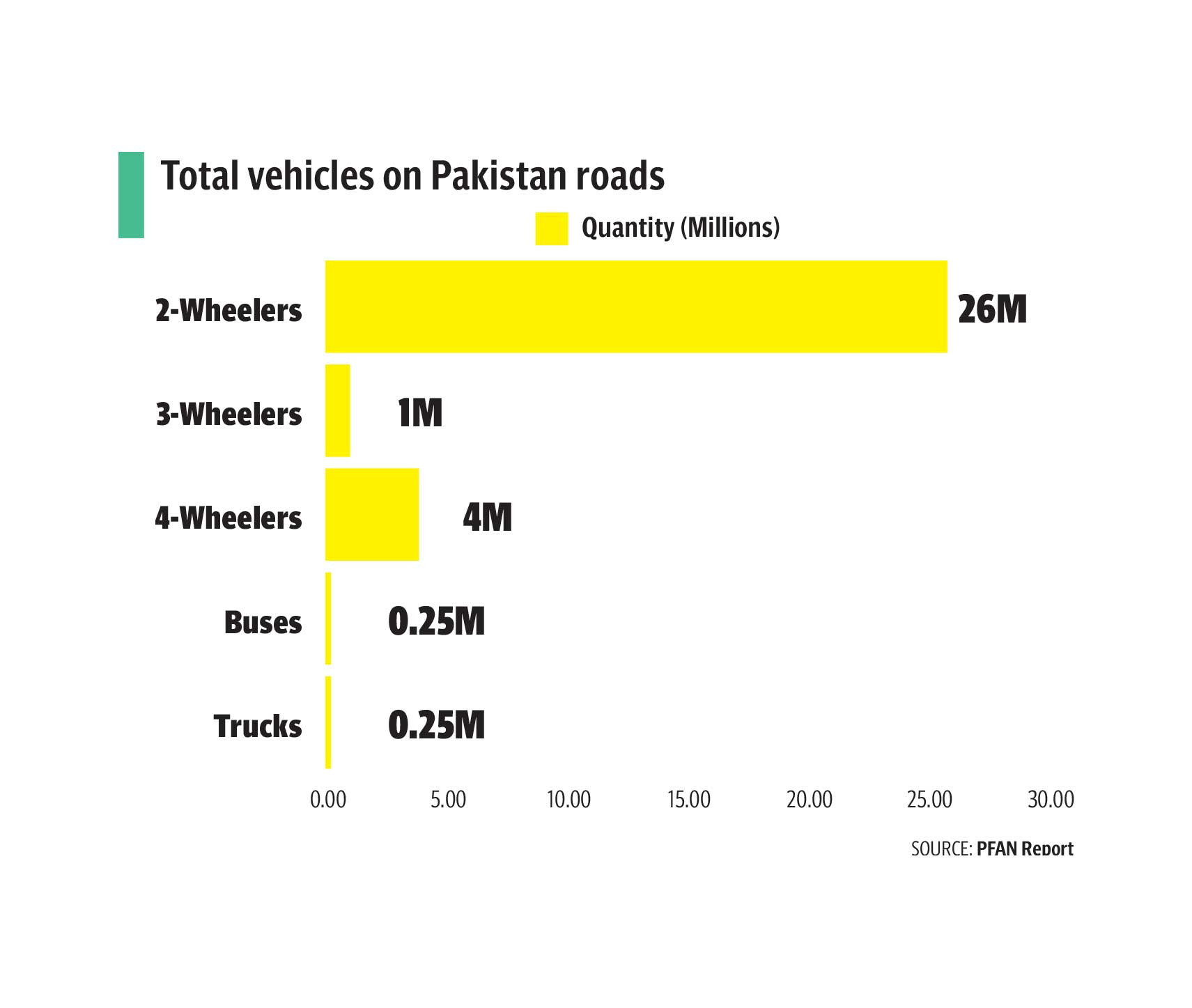

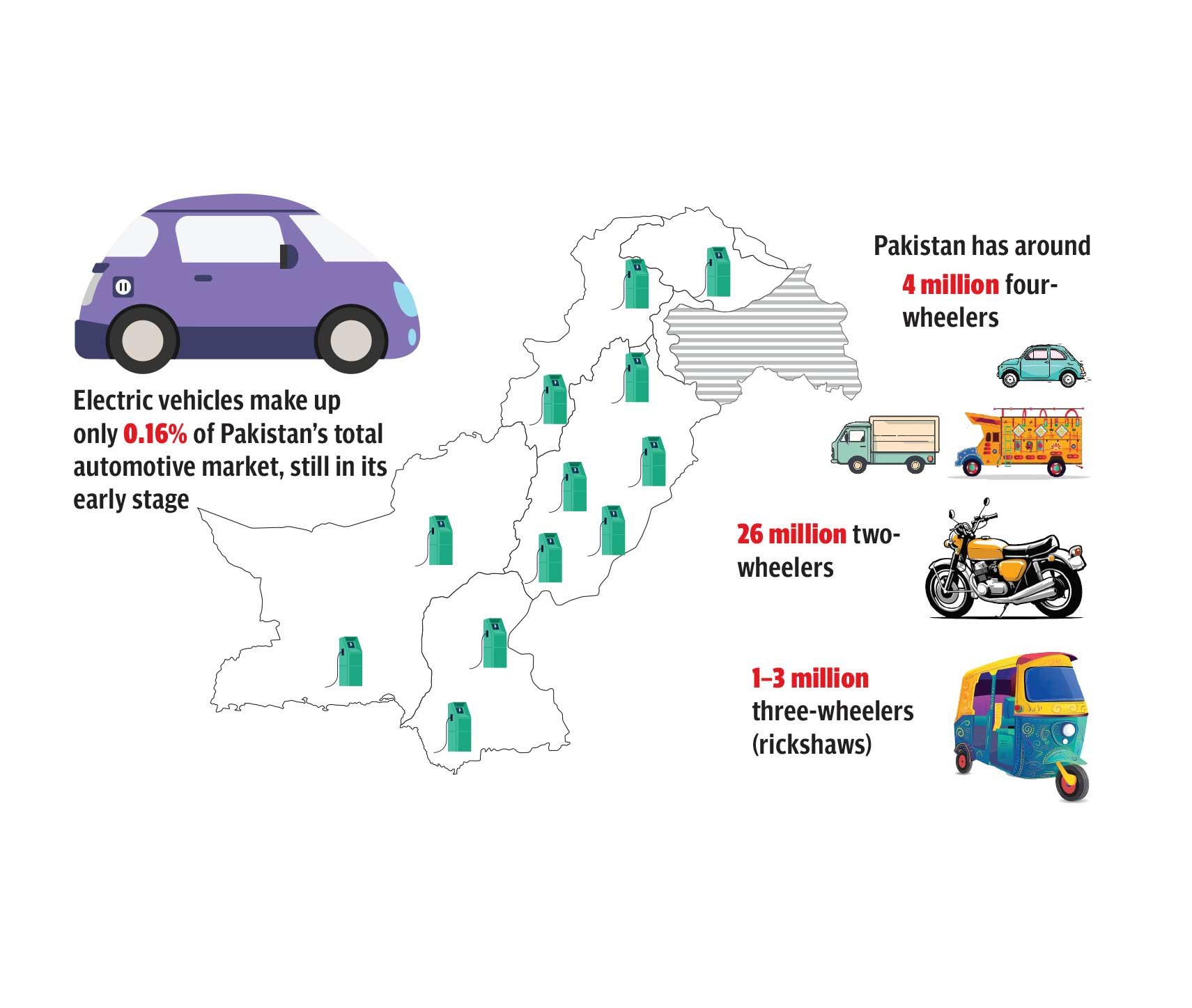

Urban road traffic is one of the biggest contributors to air pollution, and with more than 26 million two-wheelers and over 4 million registered cars on the roads, most still running on petrol, the transformation has to happen here first.

But that road isn’t exactly smooth. There are potholes everywhere, policy gaps, lack of charging stations, affordability challenges, and a public still unsure whether to trust the shift. For a country where motorcycles outnumber cars six to one, the real question isn’t how Pakistan will electrify, but where the shift will begin?

In Karachi’s Saddar area, a young delivery rider glides past rush hour traffic on a matte-black electric bike. No engine noise. No trail of smoke. Just the soft whirr of battery power. Not far from him, a university student, one of the few women in her neighborhood who rides her own scooter, navigates the main road on her white EV, past minibuses that still belch diesel fumes.

And then there’s Bilal. Office worker. Family man. He recently bought a used EV sedan, a leap of faith, really. He’s been planning a road trip to Islamabad, but each time he looks up the route, he pauses. The chargers are few and far between.

These three riders, one hopeful, one bold, one hesitant, are all part of Pakistan’s electric present. They represent the promise, the doubt, and the momentum that’s slowly building. But the bigger question remains: will the rest of the country catch up? And can the infrastructure, the policies, and the technology come together fast enough to make this transition more than a niche trend?

To understand that, we need to know where things stand now. What’s working, what isn’t, and what lies ahead.

EV snapshot of Pakistan

For a country that’s spent decades running on petrol and diesel, the idea of plugging in your ride instead of filling it up is still unfamiliar for most. And yet, something has started to move, slowly and quietly.

Pakistan’s EV footprint is still small, less than 0.2% of all registered vehicles in the country, according to figures shared by the Engineering Development Board this year. It's the kind of statistic you can miss if you blink. But it also tells you the first steps have been taken.

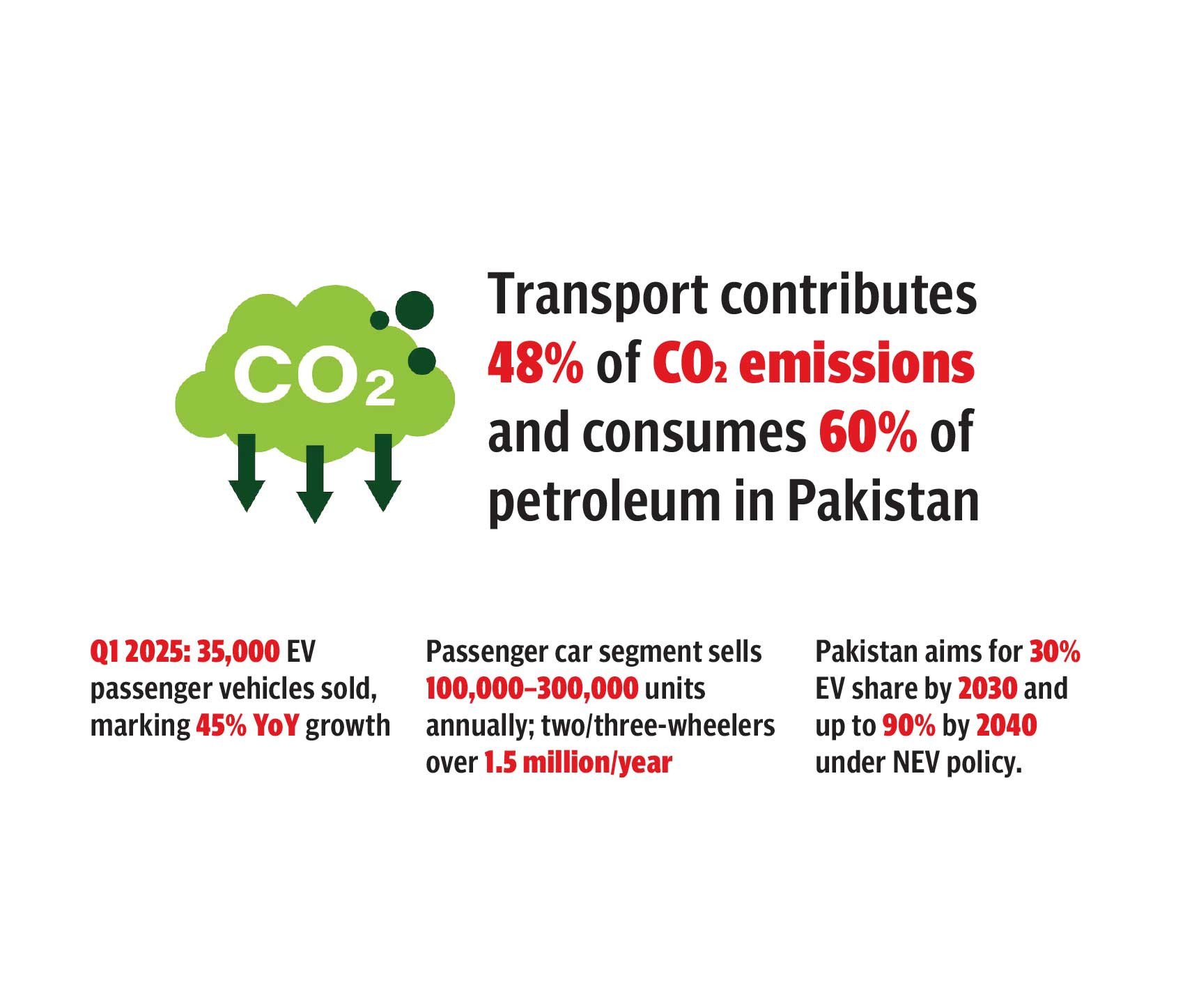

The focus so far has been on volume, and volume, in Pakistan, lives on two and three wheels. Which is why it’s not surprising that of the 57 EV manufacturing licenses issued by the government, most are for electric bikes, scooters, and rickshaws. In the last fiscal year alone, nearly 33,000 EVs were rolled out by these local players, small numbers compared to traditional vehicles, but a crucial first wave.

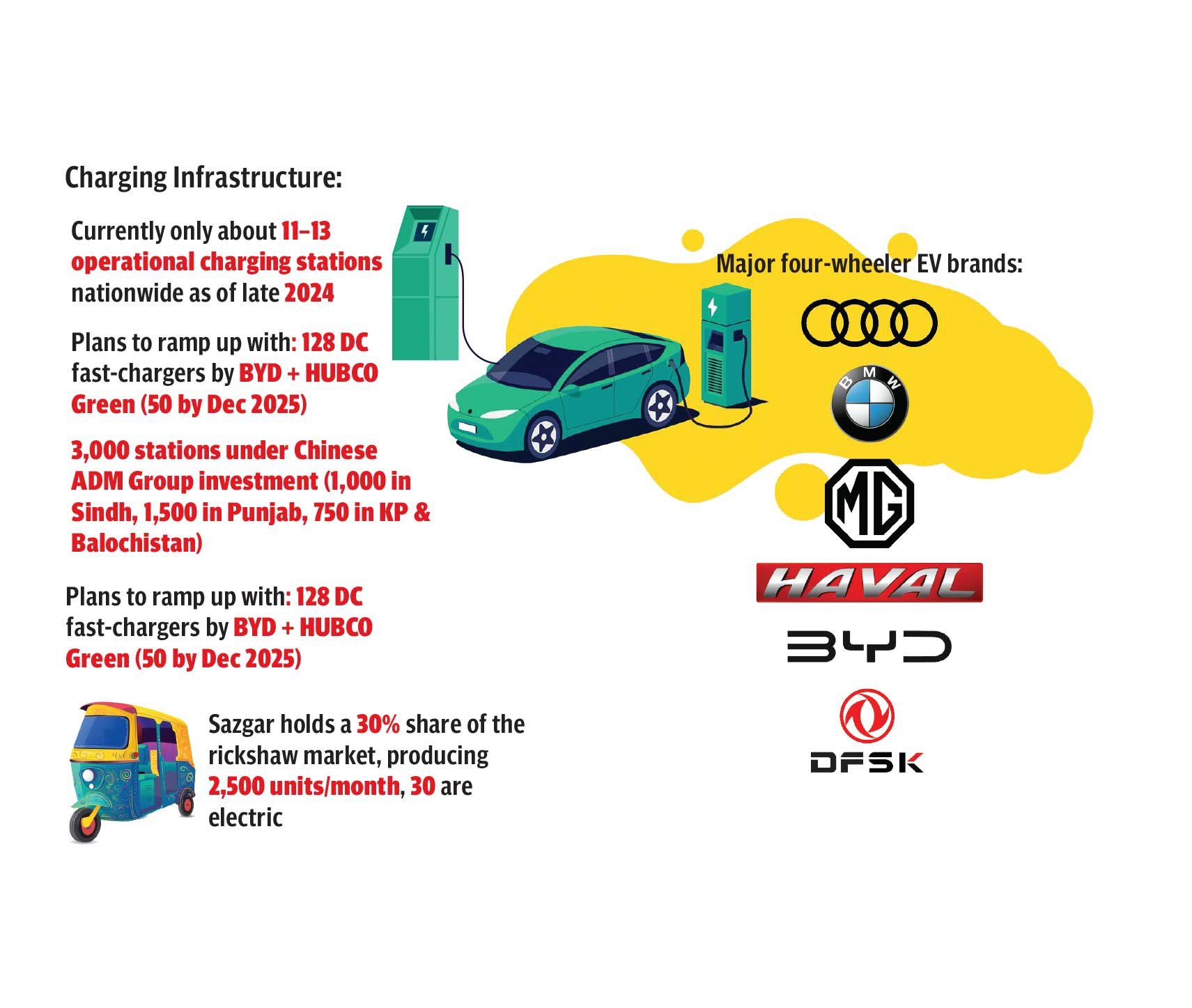

What’s lagging, though, is the infrastructure. In a country of over 220 million people, there are just a handful of public EV charging stations, most of them concentrated in Karachi, Lahore, and Islamabad. In late 2024, the number hovered just above a dozen.

But there’s momentum. Companies like BYD and Hubco Green are now working on plans to install 128 fast chargers by the end of 2025. The government says it wants to take that number to 3,000 over the coming years, with 40 locations already earmarked along motorways. The plan is to space them about 100 kilometers apart, enough, in theory, to make intercity EV travel more viable.

There’s optimism on the policy front, too. The updated National Electric Vehicle Policy (2025–2030) sets an ambitious goal: shift 30% of all new vehicle sales to electric by the end of this decade. The government is backing this with financial incentives, subsidies for over 100,000 electric bikes and thousands of e-rickshaws, including quotas reserved for women riders.

The math supports the urgency. Road transport is a major contributor to urban air pollution, responsible for close to half of it, according to various environmental assessments. Add to that the 60% chunk of national petroleum consumption that goes into fueling cars, motorcycles, buses, and trucks. The cost isn’t just environmental. It’s financial, political, and it's also showing up in people’s lungs.

But between promises and policy documents, there’s the street-level reality. The average consumer is still unsure. There’s curiosity, yes, but also hesitation. Charging availability, resale value, upfront cost, these questions don’t have clear answers yet. For now, the EV scene remains a mix of early adopters and hesitant onlookers.

The real question isn’t how Pakistan will transition, but where the momentum will start. Will it be the college kid on a cheap electric bike? The fleet operator with rickshaws to upgrade? Or the urban elite buying EVs as second cars?

Four-wheelers – big leap with big barriers

For most middle and upper-income Pakistanis, the idea of owning an electric car still sits somewhere between aspiration and uncertainty. The appeal is clear: no fuel queues, lower running costs, and greener footprint. But turning that promise into reality is another story.

Right now, four-wheeler EVs in Pakistan cater mostly to early adopters who can afford higher upfront cost and have a second car just in case. Danish Khaliq, VP Sales and Strategy at BYD/Mega Motor, sees this firsthand. “Our users are the ones who can charge at home, who are excited that a global brand like BYD is here,” he says. “They want to try it.”

But even for this niche, convenience has its limits. “There’s still dependency on commercial charging infrastructure,” he explains, especially for longer trips. And while a fast charge takes about 20 to 25 minutes, he points out it’s not unfamiliar. “Pakistan is a nation that has stood in CNG lines for an hour. So yes, 25 minutes is a lot, but we’ve done worse.”

BYD’s response has been to build smarter, not wider. Through Hubco Green, they’ve partnered with PSO, Total, and others to roll out 50 fast-charging stations by the end of 2025, with plans to double that the year after. But Danish is quick to note that hardware alone isn’t enough.

The bigger issue, he says, lies in policy design. “The government introduced a tax structure where EVs with batteries larger than 50 kWh are taxed at 18%, plus 3% more. Smaller batteries are taxed at 12.5%,” he explains. “The intention was affordability, but they’ve penalized range, which is exactly what people want in a car.” Range anxiety, he adds, remains one of the biggest psychological blocks for buyers.

Still, he acknowledges the intent. “The current auto policy was designed five years ago to attract investment, and in that, it worked. But there are nuances that need better understanding.”

Miral Sharif, Country Head at Yango Pakistan, echoes the concern but adds another layer. For a ride-hailing company, electrification isn’t just climate-driven, it’s economic. “Lowering operational costs are essential. Our pilots show EVs reduce them by 35%,” she says. “That’s a game-changer for our drivers.”

Until policy, infrastructure, and public confidence align, four-wheeler EVs in Pakistan will remain more ambition than mainstream.

Two and three-wheelers

If you want to know where Pakistan’s electric future is most likely to take root, look away from elite showrooms and towards the congested, noisy, unpredictable roads where bikes and rickshaws outnumber cars by millions. This is where the EV shift, if done right, will matter the most.

With more than 26 million motorcycles on the road, and millions of three-wheelers, the volume, and the opportunity, sits on two and three wheels. From delivery riders and gig workers to students and small business owners, this segment represents the face of urban mobility in Pakistan.

Shah Talha Sohail, co-founder and CEO of Mode Mobility, an automotive design and engineering company, has been working in this space since 2020, long before EVs became a talking point in budget speeches. “Back then, we didn’t know 2025 could be the year of EVs, and 2026 even better,” he says. “But now, people come to us wanting to buy an EV. It’s not about selling the idea anymore, it’s about helping them pick the right one.”

That shift didn’t happen overnight. It took early adopters willing to take a risk, and manufacturers willing to learn. “EVs are still a high-risk purchase,” Sohail admits. “People don’t know if the claimed battery life will hold up. But consumers are evolving. There’s some push, some pull, we’re somewhere in between. That’s actually a good place for Pakistan to be right now.”

What complicates the picture, though, is the sudden flood of opportunistic entrants. “Every morning there’s a new paddle boat and two-wheeler in the market,” Sohail says. “It’s easy to import a $300 kit from China, assemble it, and sell it for triple. But that’s not our game. Our strength is design and engineering, creating something that actually fits this market and lasts in our conditions.”

That kind of thinking, build local, build durable, is echoed by Ali Moeen Malik, co-founder of ezBike. His company started as a bike-sharing service and evolved into one of Pakistan’s few EV startups focused on manufacturing and conversion. “We realised early on that most people couldn’t afford a new EV bike,” he says. “So we started converting existing 70cc motorcycles into electric ones.”

The conversion reduced upfront costs by as much as 75%. “People were converting their bikes for around Rs60,000-Rs65,000,” he says. “Most of them recovered that money through fuel savings in less than six months.”

Cracks in the ecosystem

Even with policies in motion and private players pushing ahead, Pakistan’s EV ecosystem still has visible and widening cracks. Will the chargers be enough? Is the grid stable? What happens if EVs flood the market before the country is ready?

For now, the early adopters are those who can afford the risk. They charge their vehicles at home, install private chargers, and build in backup plans. But for the broader market, public infrastructure matters, and there, uncertainty remains.

Not everyone will charge at home. Many will depend on public chargers, especially during intercity travel. That means usage won’t be uniform, it will spike in some areas and sit idle in others. “You have to be smart about it,” Danish of BYD explains. “You won’t put charging stations in every other lane. But in malls, clubs, commercial hubs, destination charging will ensure utility.”

Infrastructure is only part of the gap. The larger concern sits with policy, and the absence of regulation. As talk around importing used electric vehicles gains traction, Danish urges caution. “In many countries, used car markets thrive, but they’re backed by strict emission testing. Each year, you have to get your car tested. If it doesn’t meet the standard, you don’t get the permit. That system doesn’t exist here.”

Without monitoring, he warns, the system could backfire. “If you start importing cars that are five or 10 years old, and there’s no oversight on emissions, you’re going to create more problems than you solve.”

The next two years

For all the momentum, pilots, and promises, Pakistan’s EV story is still in its fragile early chapters. The next 18 to 24 months could either cement the shift, or expose the gaps in policy, planning, and public trust. Everyone in the industry agrees: this is a make-or-break window.

For Miral of Yango, scale will only come if the ecosystem moves forward together. “It’s a chicken-and-egg problem,” she says. “You could go out and buy EVs at scale, but if there aren’t enough chargers, that’s a problem. Or the vehicles may not be suited for a taxi model. So, a lot of parallel work is needed.”

“From our side, what I foresee by 2026 is that 20–25% of the fleet we operate through partners would have shifted to EV,” she says. And they’re not limiting themselves to four-wheelers. “We’re working to electrify two and three-wheelers too, because that’s where most of the pollution and affordability issues sit.”

She points to government efforts, federal and provincial, as encouraging signs, especially around policy and pricing support. “We are headed in the right direction,” she says. “But for this to really work, the entire value chain, from financiers to manufacturers to the government, has to stay aligned.”

Sohail of Mode Mobility believes that Pakistan is inching toward its EV tipping point. “There’s some pull and some push, we’re somewhere in between,” he says. “That’s actually a good place for a developing country like ours.” For now, his company continues to balance education and engineering, working to build EVs that can survive local conditions, even if that means slower growth. “The early adopter phase is still here,” he says, “But it won’t last much longer.”

Malik of ezBike sees the next phase as less about hype and more about structure. His company has already moved from experimentation to serious R&D. “There’s a certain level of trial and error involved, but that’s how you build better products.” For him, the 18–24 month horizon is about consolidation, refining products, expanding conversions, and figuring out how to make EVs work for the average Pakistani commuter.

There’s no shortage of ambition. But whether that ambition translates into adoption depends on what happens next: clearer policies, better access to financing, smarter infrastructure, and products people actually trust.