On June 1, Ukraine launched one of the boldest and most complex operations of the drone warfare era. Codenamed Spider’s Web, the mission saw over 100 drones strike deep into Russian territory — far beyond the frontlines of the war, and seemingly out of nowhere.

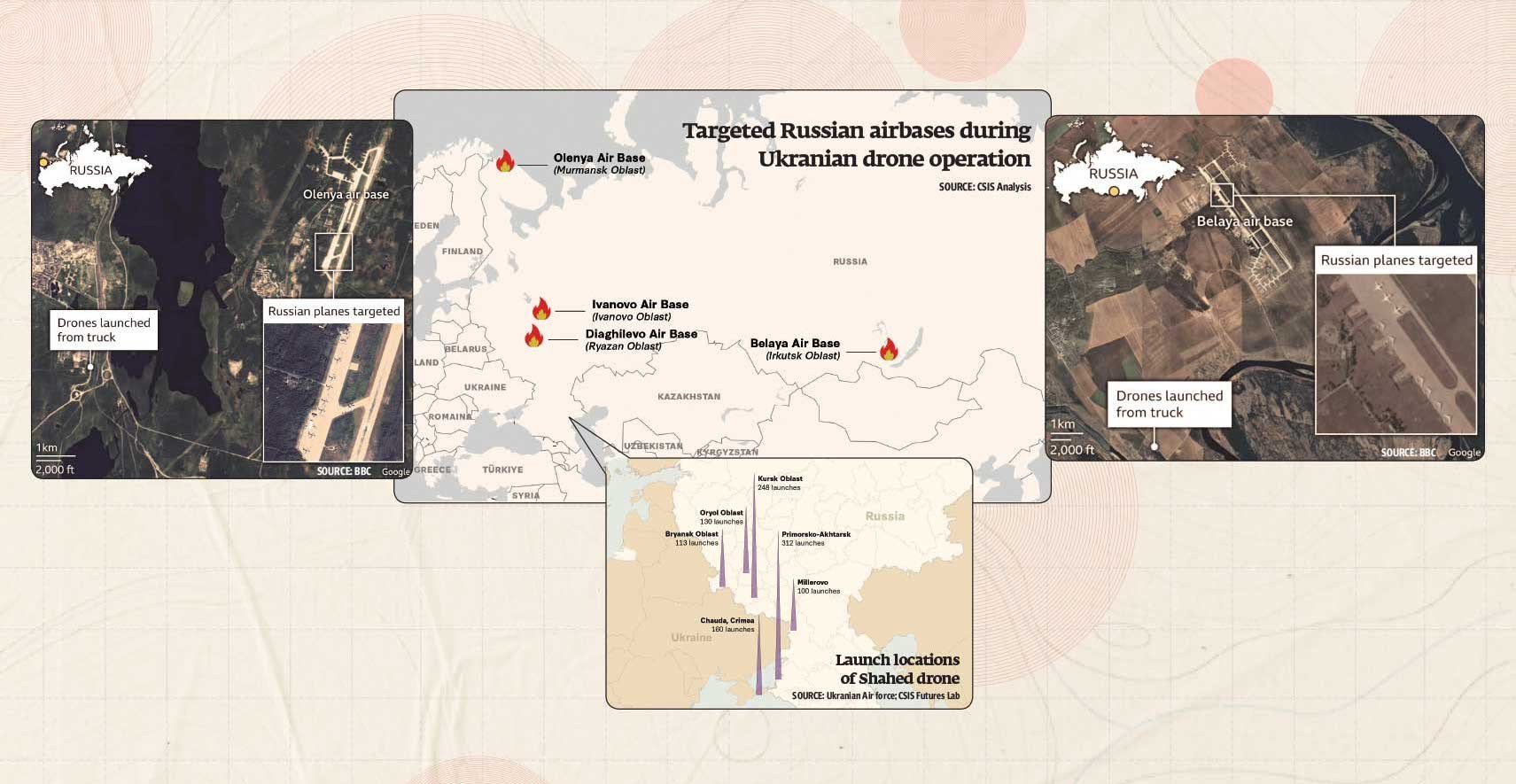

According to Russia’s Defence Ministry, airbases in five regions — Murmansk, Irkutsk, Ivanovo, Ryazan, and Amur — came under attack. Moscow acknowledged aircraft damage in Murmansk and Irkutsk, while insisting the remaining drones were repelled. Ukraine, however, claimed the assault was far more devastating: 41 strategic bombers hit and “at least” 13 destroyed.

The aircraft targeted were some of Russia’s most prized strategic bombers: Tu-95s, Tu-22s and Tu-160s, all of them long-range, missile-carrying platforms that are no longer in production and have no immediate replacements. These Cold War-era bombers form a key component of Russia’s nuclear triad.

Independent analysis lends weight to Ukraine’s claim of damages. The BBC, citing satellite imagery from Capella Space, confirmed at least four long-range bombers were destroyed at Belaya airbase. Ukrainian drone footage released shortly after showed direct hits on a Tu-95, reinforcing the evidence.

18 months in the making

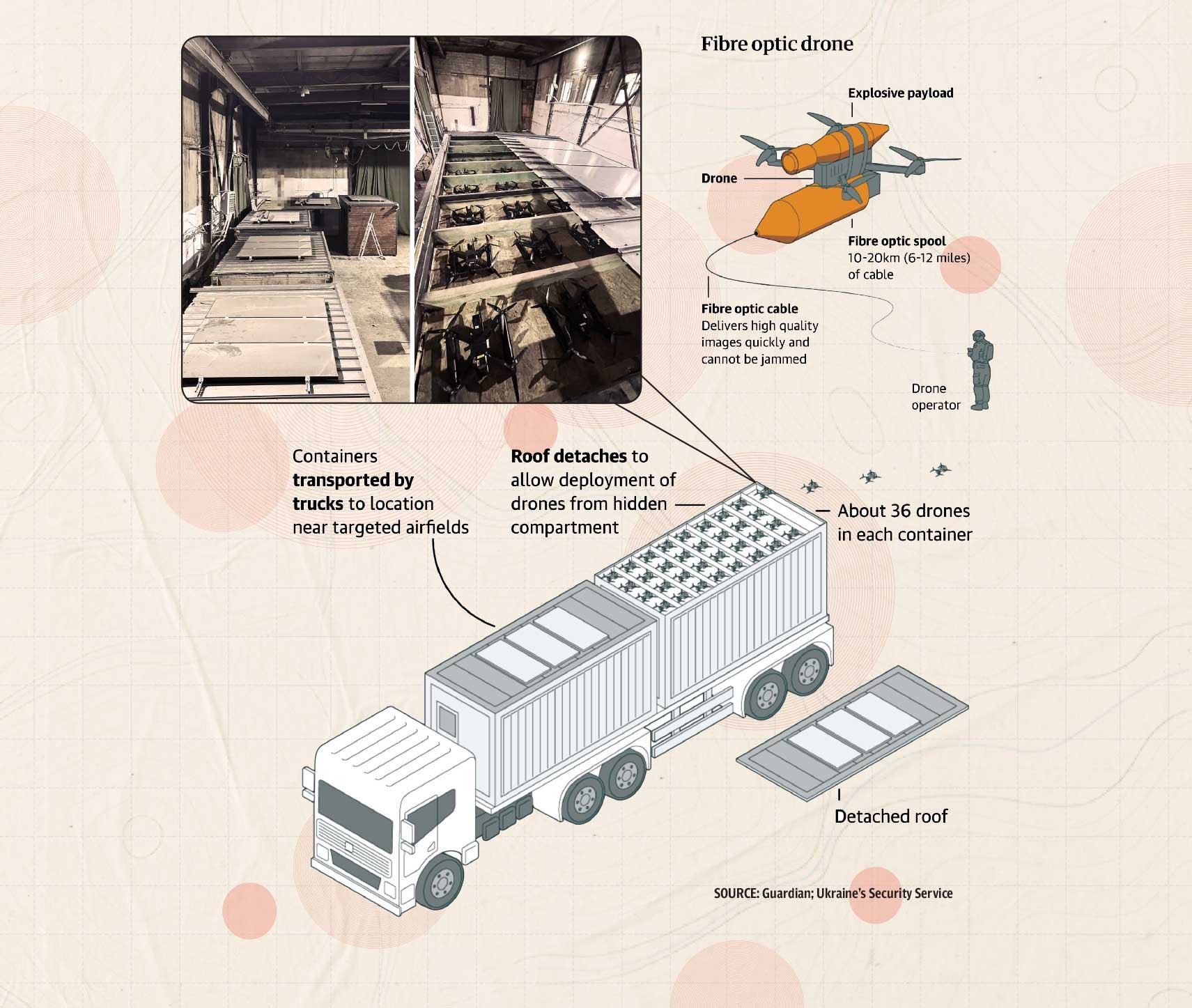

Ukraine’s Security Service (SBU) reportedly orchestrated the operation over a period of 18 months. In a statement, SBU chief Vasyl Maliuk revealed how the drones had been stealthily smuggled into Russia: packed inside wooden cabins mounted on trucks, hidden beneath remotely operated, detachable roofs.

These trucks, Maliuk said, were driven to locations near airbases by unsuspecting drivers who were allegedly unaware of the drones inside. Once in position, the drones were launched straight from the lorries. Footage circulating online shows one such drone emerging through the roof of a vehicle.

Russian Telegram channel Baza, known to have ties to state security services, reported that all drivers gave similar testimonies. They had been hired by intermediaries posing as businessmen to transport wooden cabins and were later instructed via phone where to park. Once the trucks were in place, the drones were activated remotely.

The SBU also released photos showing dozens of sleek, compact black drones — reportedly first-person view (FPV) drones — neatly packed in wooden crates inside a warehouse. Russian military bloggers later geolocated the site to Chelyabinsk.

The drones were piloted remotely using ArduPilot, an open-source software platform that supports autonomous navigation through dead reckoning — a method that calculates position based on a drone’s previously known location, direction, and speed, without relying on satellite navigation. This allowed the drones to remain operational even in areas where GPS jamming is prevalent.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky later confirmed that each drone had its own human pilot, launching and steering it from afar. One analyst noted that the drones’ use of dead reckoning made them nearly immune to electronic interference. The same analyst also suggested the drones likely used local SIM cards to transmit positional data and digital communications over mobile networks, allowing for remote piloting and even real-time high-resolution video streaming.

To overcome the inevitable delays in long-distance communication — and to maintain function even in the event of a signal loss — the drones may also have been equipped with onboard artificial intelligence (AI). According to a report by the Kyiv Post, Ukraine trained AI systems specifically for Spider’s Web using hundreds of images of Russian bombers housed at the Poltava Museum of Heavy Bomber Aviation. These images were used to identify vulnerable areas of the aircraft, allowing algorithms to guide drones in autonomously recognising and striking their targets, even without real-time human input.

‘Strategic vulnerability laid bare’

Following the operation, President Zelensky triumphantly posted on social media that Spider’s Web had used 117 drones in total. The mission, he wrote, had taken “one year, six months and nine days” to prepare.

According to the SBU, the estimated cost of the damage inflicted on Russia's air power was $7 billion — a staggering figure in both financial and strategic terms.

Speaking to The Express Tribune, Dr. James Rogers, Executive Director at Cornell’s Brooks Tech Policy Institute, warns that this is not just a battlefield innovation — it’s a strategic vulnerability now laid bare. “You don’t have to run the gauntlet across Russia anymore,” he says. “These smaller systems can fly so low, and they are incredibly difficult to defend against.” For states that have long relied on geography for protection — like Russia’s remote Arctic airbases or even NATO’s scattered drone-operating outposts — this raises uncomfortable questions.

“Every airbase can’t have bespoke air defences,” Dr. Rogers adds. “Urban areas can’t deploy GPS jammers or microwave weapons without impacting civilian life. And even in rural areas, the numbers just don’t add up. Russia likely deprioritised Murmansk and Siberia for this reason.”

The same logic could soon apply to US and NATO’s expeditionary micro-bases and even civilian infrastructure. Dr. Rogers cites recent sabotage incidents across Europe — “the Heathrow substation, the Cannes Film Festival blackout, the French rail system disruptions” — as troubling signs of hybrid threats that may soon include commercial surface and underwater drones.

Fleeting win or game-changer?

Dr. Malcolm Davis, senior analyst at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI), calls the attack “an important strategic strike with high symbolic value.” Though he stops short of comparing it to a “Russian Pearl Harbor”, as some observers immediately labeled it, Dr. Davis notes the precision and scale: “Containerised munitions, precision FPV drones, Russian drivers unwittingly carrying payloads — this was 18 months of sophisticated intelligence and operational planning.”

Yet he also cautions against overstating its impact. One especially sensitive concern is whether the attack’s targeting of strategic bombers, technically part of Russia’s nuclear triad, risked escalation. Dr. Davis notes that while Tu-95s and Tu-22s were struck, the Tu-160 fleet seemingly remains intact, and Russia has not reached the nuclear red line.

“Yes, it hit Russia’s long-range bomber fleet hard, especially Tu-95s and Tu-22s. But many Tu-160 Blackjacks remain. Russia retaliated quickly with bomber-led strikes on Ukrainian cities. Strategically, the war remains unchanged unless Ukraine’s international backing falters,” he shares.

“Technically, yes — this could be seen as an attack on nuclear forces,” Dr. Davis explains. “But using that as a justification for tactical nuclear retaliation is far more complex. It would break the nuclear taboo that’s held since Nagasaki. The global political cost — alienating BRICS allies like China or inviting direct NATO intervention — would likely outweigh any benefit for Russia.”

Still, the threshold exists. The danger is not that Spider’s Web will provoke nuclear retaliation today, but that future strikes — perhaps by actors without the same geopolitical constraints — might not show such restraint.

That strategic dimension carries existential weight. Dr. Davis warns that if the United States abandons Ukraine, and European nations fail to fill the void, “we’re either looking at a prolonged stalemate — or a probable Russian victory.” In that context, Spider’s Web may be a fleeting tactical win rather than a game-changer.

‘The cheap, the small, the many’

That said, the attack exposed an uncomfortable truth for advanced militaries worldwide: traditional platforms — like bombers, tanks, and airbases — are now vulnerable to low-cost, high-impact systems. Dr. Davis calls this the era of “the cheap, the small, and the many.”

“Drone warfare is here, and it’s here to stay,” he says. “For a fraction of the cost of advanced jets or warships, you can build precision strike capabilities that produce outsized effects.” What Ukraine demonstrated was disruptive innovation in real time, a warning to military planners still invested in expensive, legacy systems.

Whether Moscow confirms the full scale of the losses or not, Spider’s Web marks a turning point in modern warfare: a glimpse into a future where remotely operated, AI-guided weapons can be smuggled across borders and launched from within.

Blueprint for non-state actors?

While this particular operation was carried out by a state actor — Ukraine — against an invading force in the context of open war, it also raises disquieting questions about the future. Spider’s Web may not only represent the evolution of state-led asymmetric warfare — it may also serve as a dark prototype for tactics that could be adopted by non-state actors.

Could a similar operation be replicated by terror groups or insurgent movements — organisations that lack access to fighter jets, long-range missiles, or satellite infrastructure, but have access to consumer drones, open-source software, and Internet connectivity? Could this technology serve as a great equaliser, enabling them to threaten or damage the strategic capabilities of far more powerful militaries?

The most chilling prospect is that Spider’s Web may be copied not just by states, but also by militant groups. Dr. Rogers points out that the parts used in such attacks — consumer-grade drone components, open-source flight software, SIM card-based communication — are nearly impossible to regulate through export controls. “During a UN investigation, we found no single piece of tech you could realistically lock down to stop this threat,” he says.

“We’re entering a phase where violent non-state actors can leverage large language models to become self-taught engineers — capable of designing, modifying, and deploying advanced military technologies,” says Dr. Rogers. “The second threat is what happens when the Ukraine-Russia war eventually ends. Both sides have produced millions of advanced drones. If even a fraction of that arsenal enters the global arms market, it’s only a matter of time before these capabilities end up in the hands of insurgent groups or proxies And who knows what drone capabilities were left behind by departing US forces deployed elsewhere.”

Some aspects of that future are no longer theoretical. The January 2024 drone strike that killed three US personnel in Jordan — conducted by an Iranian-aligned militia — was the first time hostile enemy airpower claimed American lives since Korea. Spider’s Web, in this light, may be less an anomaly than a warning.

The ingredients used in Spider’s Web — commercially available drones, repurposed open-source software, AI trained on publicly accessible imagery, and civilian transport vehicles — are, disturbingly, within reach of many well-funded non-state actors. The concept of smuggling drones into a target country in innocuous-looking trucks, hiding them in wooden crates, and launching them via remote command is alarmingly replicable.

Moreover, the operation hints at a future where nation-states may use such tactics through proxies, employing drones to carry out precision strikes under a veil of plausible deniability. With no boots on the ground and no need for overt military engagement, Spider’s Web-style attacks could blur the line between cyber operations, sabotage, and conventional warfare. A deniable drone strike that cripples an adversary’s airbase or power grid may one day fall into the grey zone between war and peace — a tempting tool in an era of hybrid conflict.

Just as roadside IEDs reshaped the battlefield in Iraq and Afghanistan, these low-cost, high-impact drone tactics could redefine the modern theatre of war.

What Ukraine achieved with Spider’s Web was unprecedented. But what it may have inadvertently unleashed is a new doctrine of distributed, deniable, and devastating warfare — one that doesn't require control of the skies, only control of the code. The consequences are profound — not only for military strategists and national security planners but also for civilian infrastructure, global arms control regimes, and the future of warfare itself.