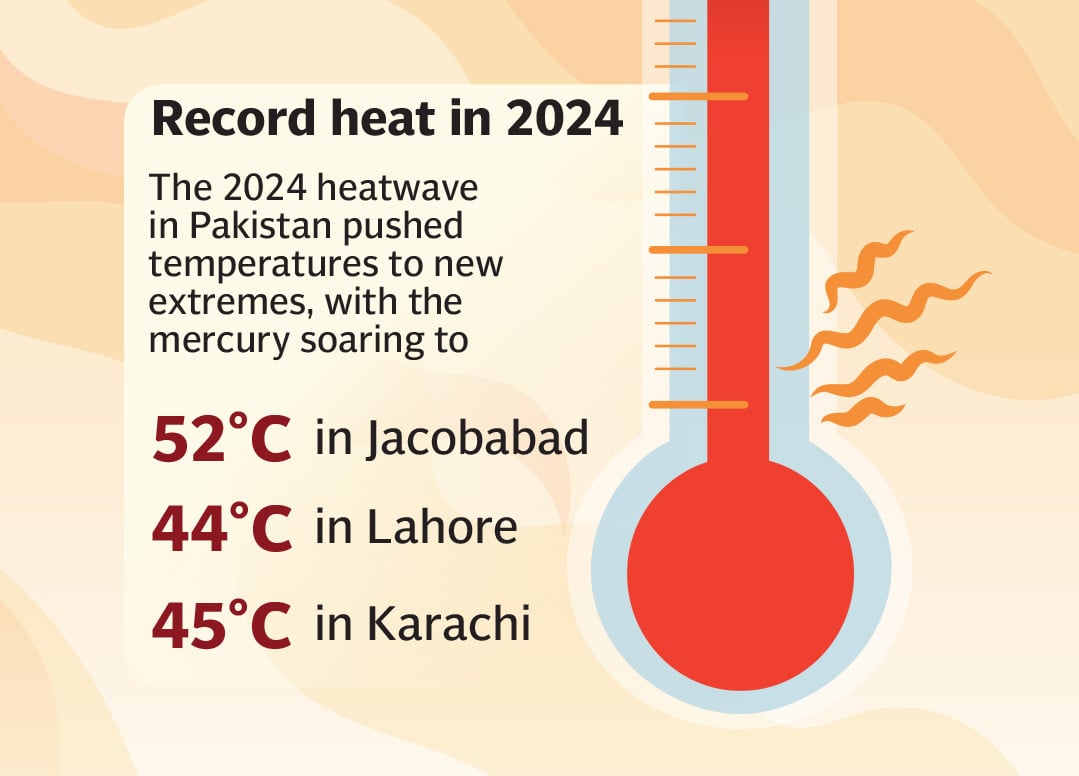

From the parched streets of Jacobabad to the sprawling heat islands of Karachi, Pakistan is confronting a merciless new reality. Each year, the heatwave season creeps earlier into the calendar, stretches longer, and scorches harder.

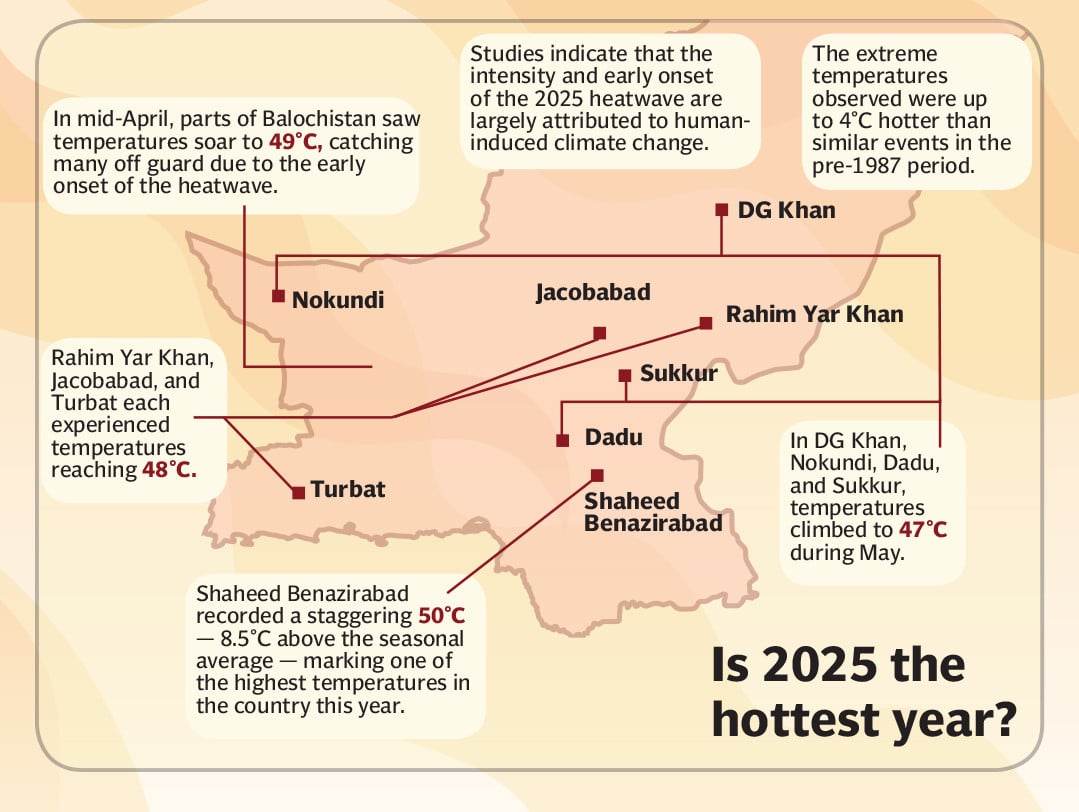

In 2025, temperatures soared to devastating heights — Shaheed Benazirabad, formerly known as Nawabshah, sweltered at 50°C, a blistering 8.5 degrees above the seasonal norm. Rahim Yar Khan, Jacobabad, and Turbat were not far behind, baking under 48°C heat, while parts of Balochistan hit a staggering 49°C in April, a month traditionally reserved for milder warmth.

Such extremes no longer feel like anomalies but a constant reminder of a shifting climate reality. The flames licking across Pakistan are stoked by more than just sun and dust — human-caused climate change is rewriting the country’s weather narrative at an unforgiving pace. This is no longer a distant threat – it is an unfolding emergency that penetrates every layer of life, from the fragile wheat crops to the cities where millions seek refuge from the punishing temperatures.

Scientists have traced this deadly heat back to its root cause – the accelerating rise in global temperatures driven by human activity. Research led by Dr Friederike Otto and Dr Mariam Zachariah of Imperial College London’s Grantham Institute has quantified the human fingerprint on this intensifying scorching spell. Their climate attribution study reveals that the 2022 spring heatwave that swept across India and Pakistan — which saw March record India’s hottest temperatures since 1900 and similarly shatter records in Pakistan — was made roughly 30 times more likely by greenhouse gas-driven climate change. These findings leave no room for doubt – the harsh conditions that kill, disrupt, and destroy are no accident of nature but a product of our warming planet.

“In this part of the world,” Zachariah explains in an article published on the university’s website, “heatwaves are particularly hazardous to the 60% of the population who work outdoors and are therefore limited in their means to cope.” For Pakistan, where the majority labour in fields, construction sites, and open markets, this translates into a deadly assault on human health.

The relentless sun’s glare in March 2022 was coupled with an alarming deficit in rainfall — 62% below average for Pakistan — amplifying drought and triggering early crop failures. Wheat, the country’s staple grain, withered under the unyielding heat and thirst, threatening food security at a critical juncture. Meanwhile, urban centres faced soaring electricity demand as millions struggled to cool homes in a climate system ill-prepared for such extremes, leading to widespread power outages.

These environmental changes amplify the toll on human health and livelihoods. Pakistan’s vulnerability is further exacerbated by rapid urbanisation and deforestation. Cities like Karachi and Lahore, sprawling under concrete and asphalt, have morphed into heat islands — vast ovens where temperatures are far higher than surrounding rural areas. Here, the air itself becomes a furnace, and the night offers little reprieve, intensifying heat stress and straining already fragile healthcare systems.

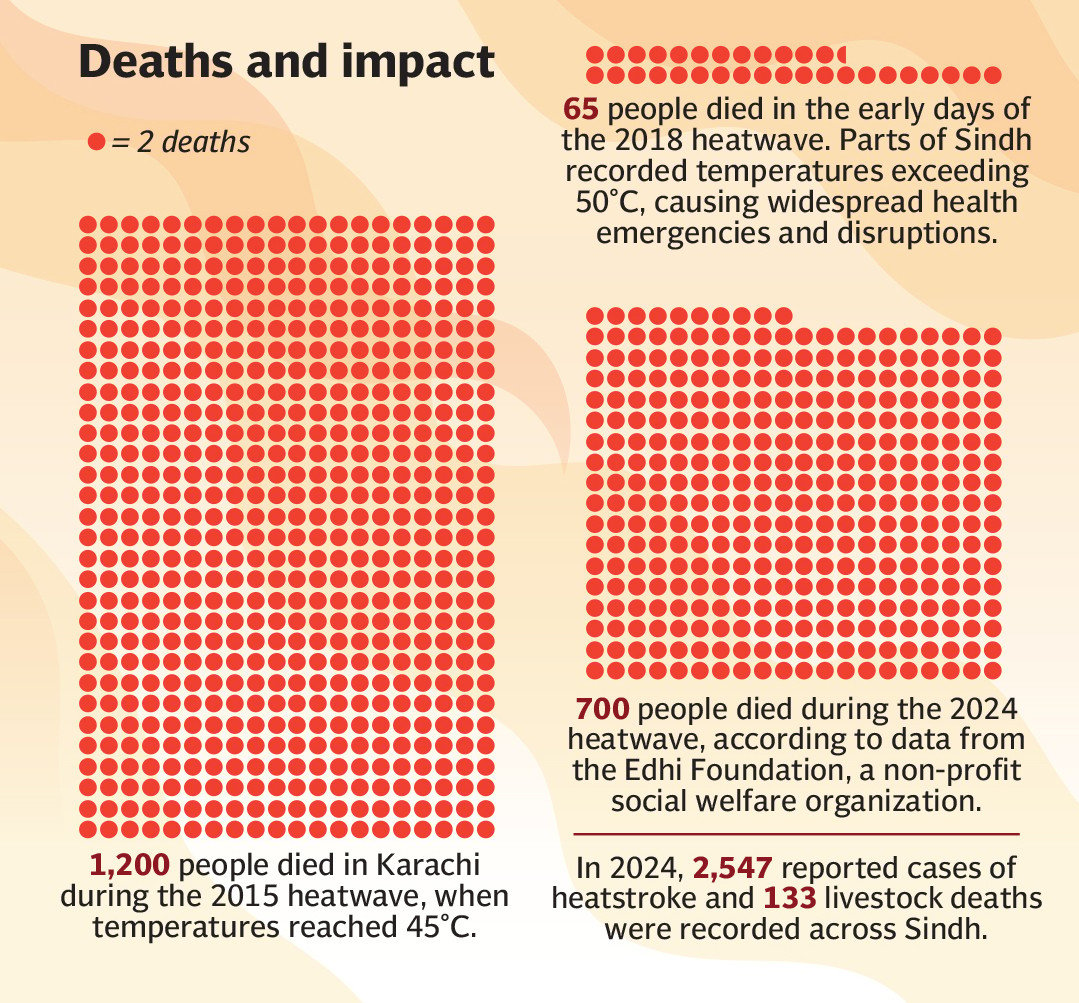

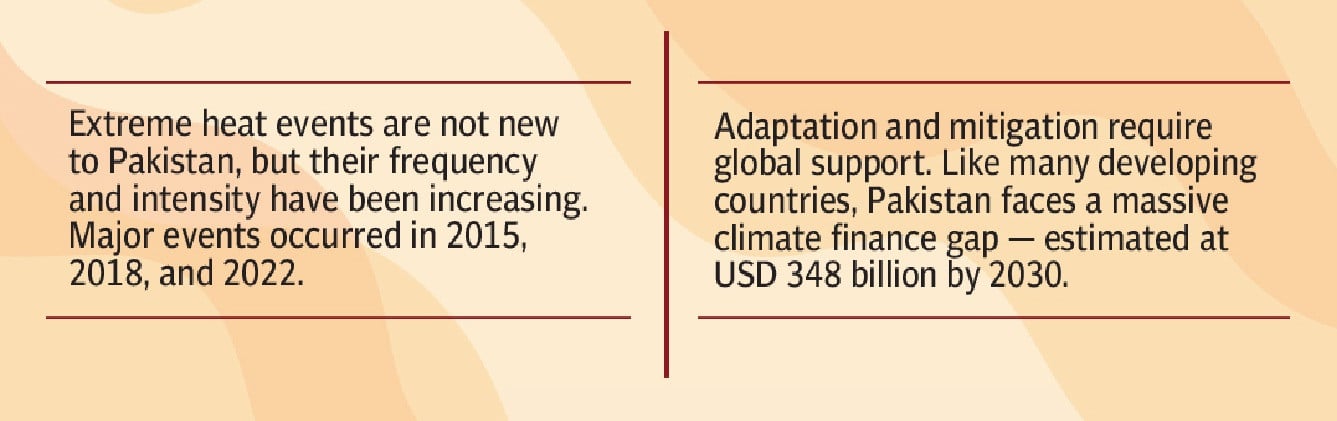

The grim statistics offer a chilling introduction to an escalating crisis. During the 2015 Karachi heatwave, temperatures soared to 45°C, resulting in more than 1,200 deaths. Three years later, Sindh witnessed another deadly wave with temperatures crossing 50°C and dozens of heat-related fatalities. Last year's blistering spell was no less merciless – 2,547 heatstroke cases and 133 livestock deaths were recorded in Sindh alone, with total deaths estimated at over 700 across the country.

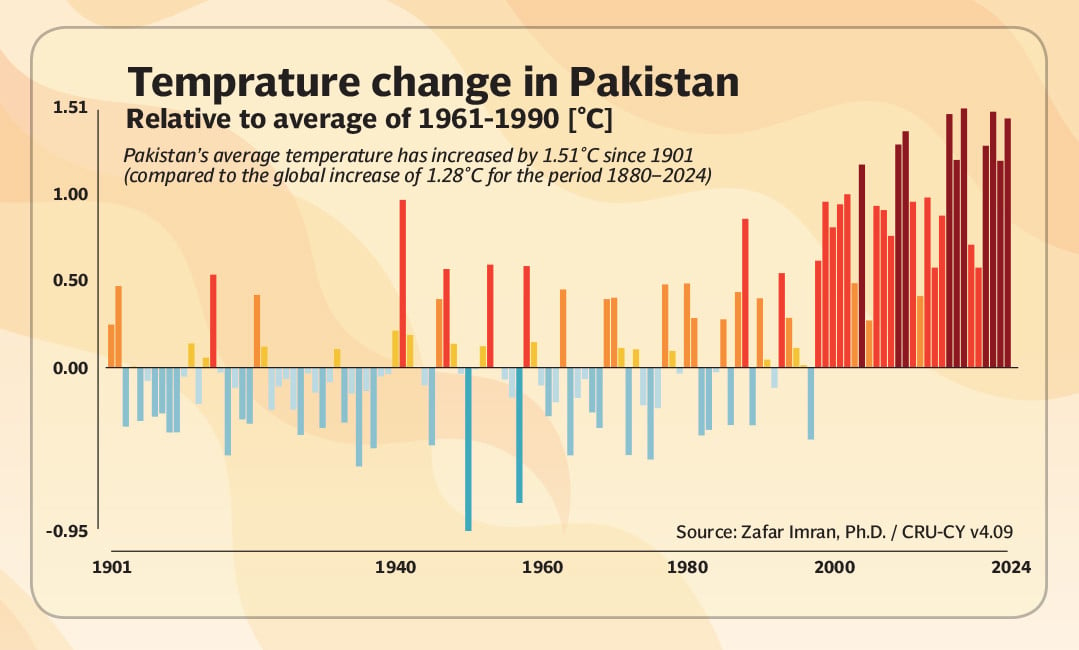

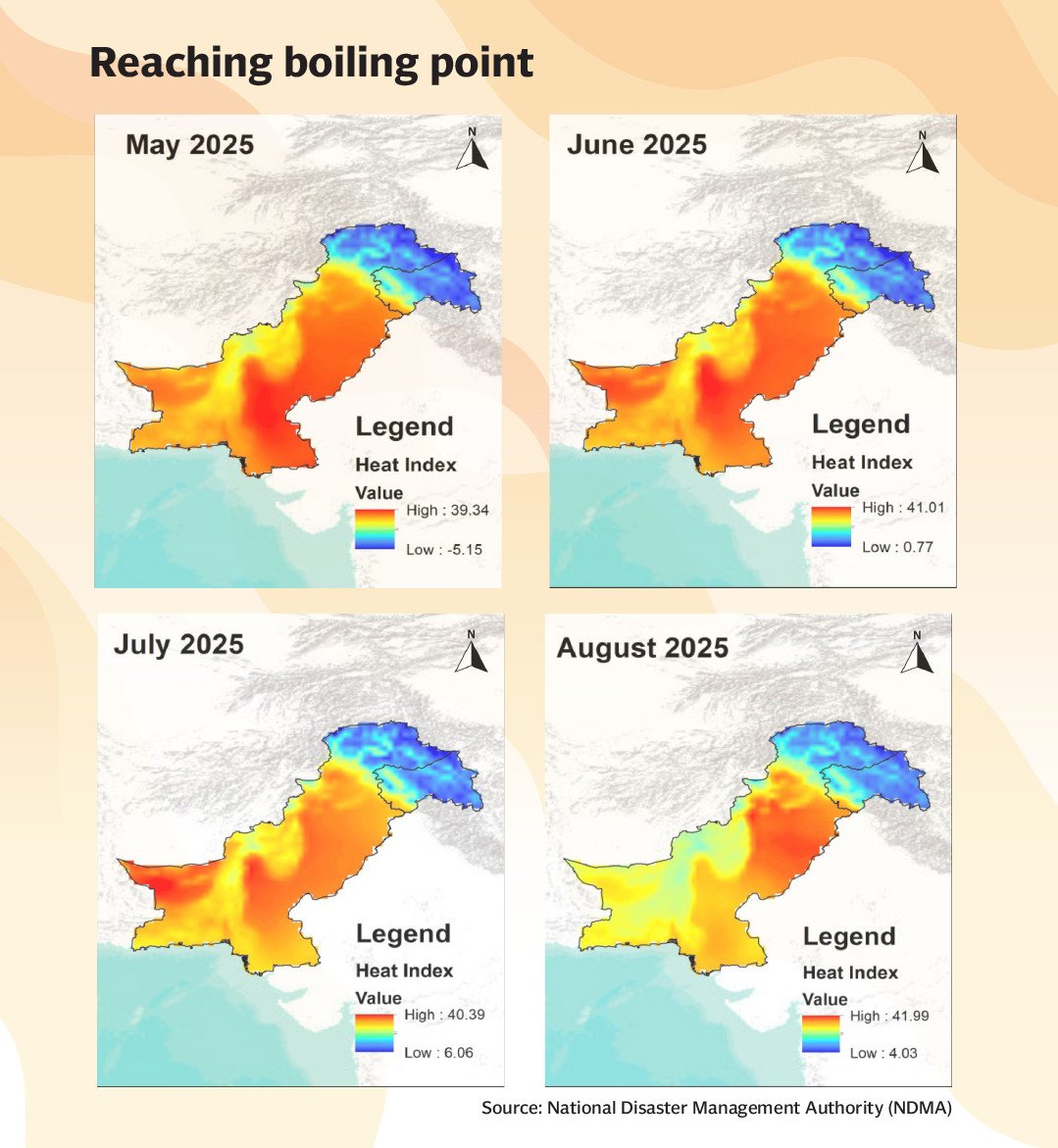

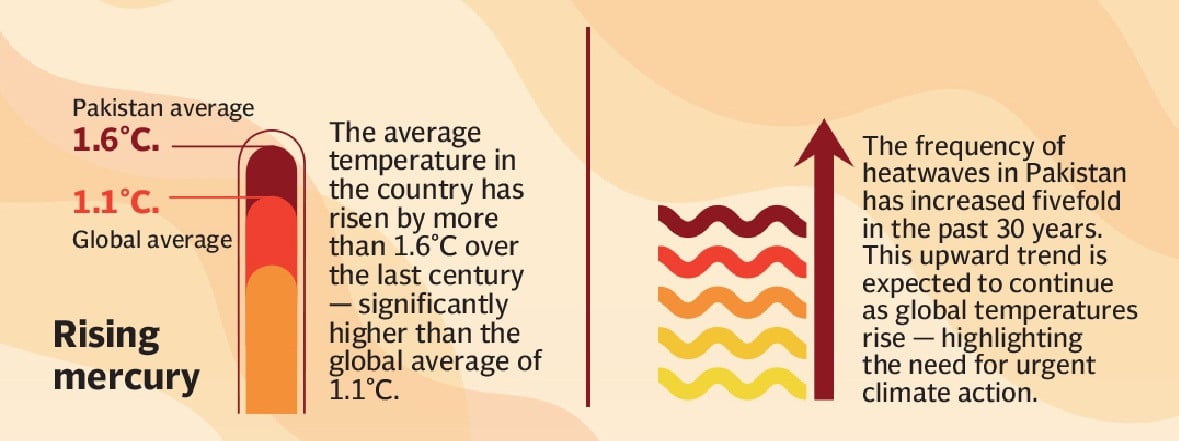

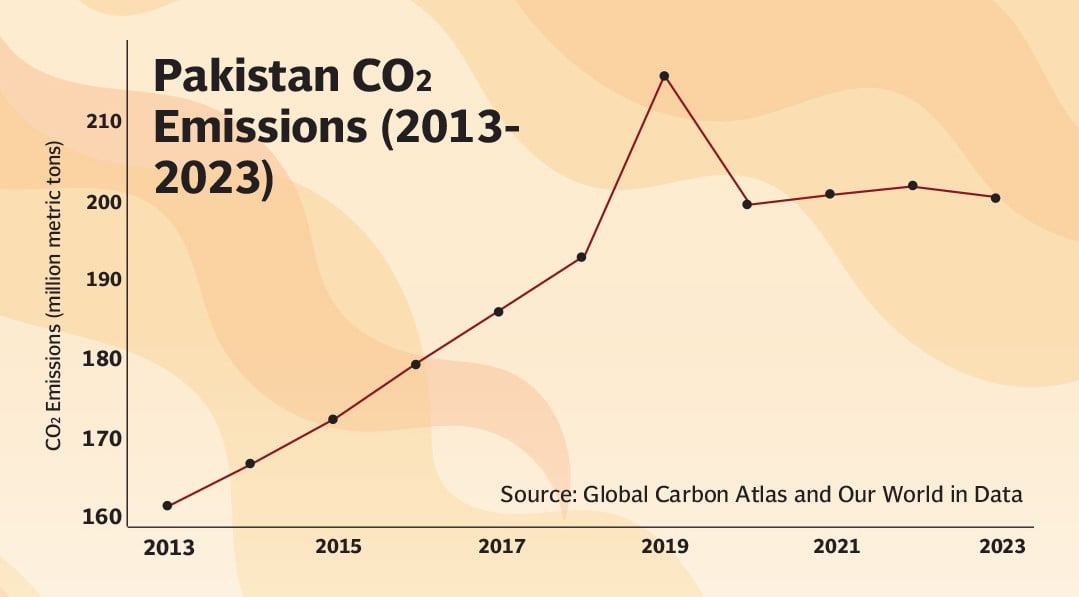

Research shows that the frequency of such brutal heat waves has increased fivefold in the past three decades, mirroring a rise in average national temperatures of more than 1.6°C over the last century — a rate significantly higher than the global average of 1.1°C. This relentless upward trajectory promises a future where punishing temperatures, once rare events, become regular features of Pakistan’s climate landscape.

The international study cautions that if global warming breaches the 2°C climate threshold, such extreme heatwaves will occur as often as every five years. Alarmingly, this prediction may underestimate the reality for Pakistan, where long-term, reliable climate data remain scarce. And without urgent mitigation and adaptation, the country faces a mounting toll of death, disease, and economic devastation.

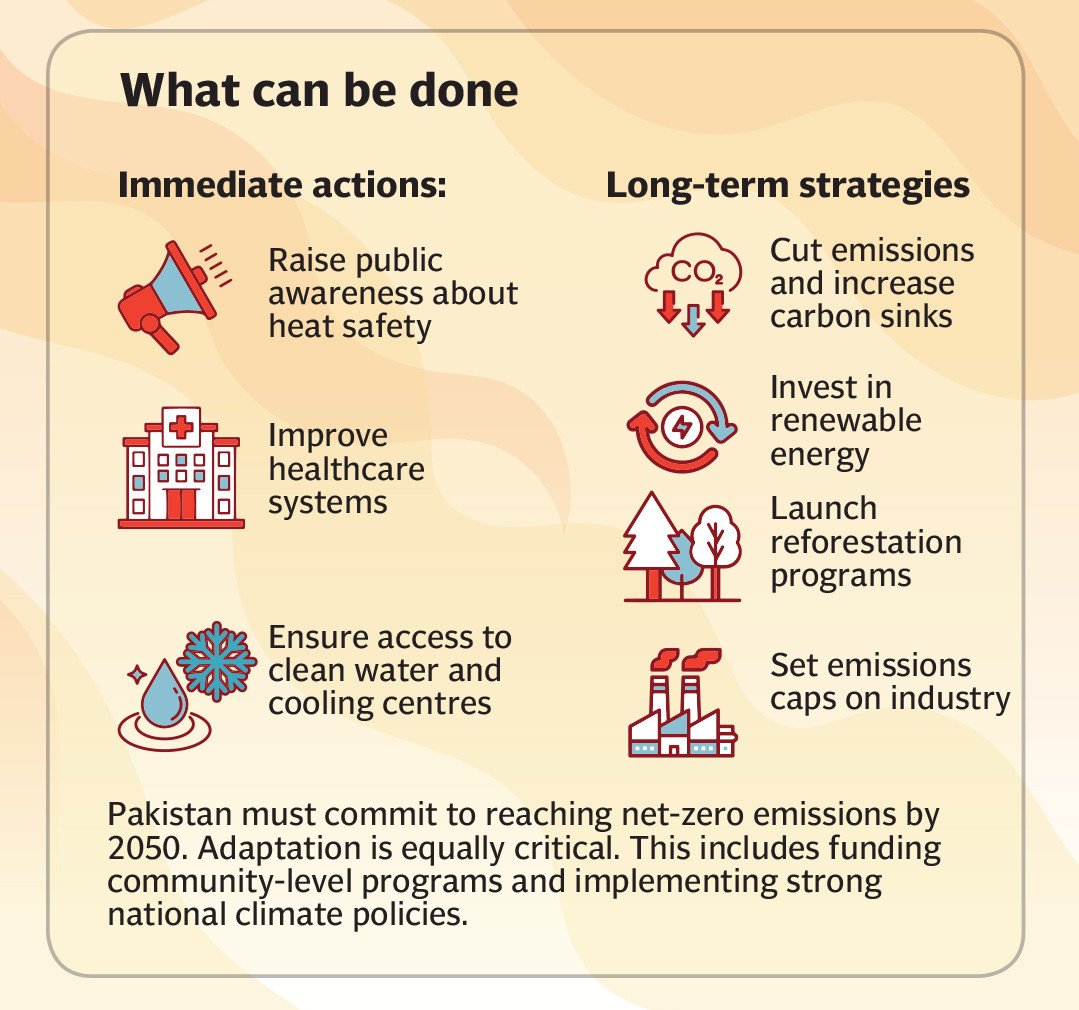

If that wasn't enough, the country's climate finance gap — estimated at a staggering $348 billion by 2030 — further hinders efforts to protect its people and environment. This financial shortfall limits investments in infrastructure to withstand extreme heat, early warning systems, and resilient agricultural practices. While neighbouring India has made strides in implementing Heat Action Plans covering 130 cities and towns, Pakistan’s progress remains fragmented, leaving millions exposed.

The stakes could not be higher – extreme heat events are now the deadliest extreme weather globally, disproportionately affecting the most vulnerable – outdoor workers, the elderly, the urban poor. They strain health services, reduce labour productivity, destroy crops, and intensify conflicts over water and resources. In Pakistan, the intersection of geography, poverty, and climate change compounds this threat more than any other country.

The struggle with scorching conditions is a microcosm of climate change’s devastating reach. As Otto notes in the article, “as long as greenhouse gas emissions continue, events like these will become an increasingly common disaster.” The melting glaciers, intensifying storms, and rising seas of one region ripple across continents, testing the resilience of societies worldwide.

For Pakistan, experts agree, the path ahead is daunting but unmistakable – decisive climate action cannot wait. The decisions taken now—in policy, energy, land use, and international cooperation—will shape the fate of millions facing intensifying heat and hardship.

The question is no longer if Pakistan will endure more brutal heatwaves—it already does. The urgent challenge is how the country, with global support, will confront this relentless reality.

A new climate baseline

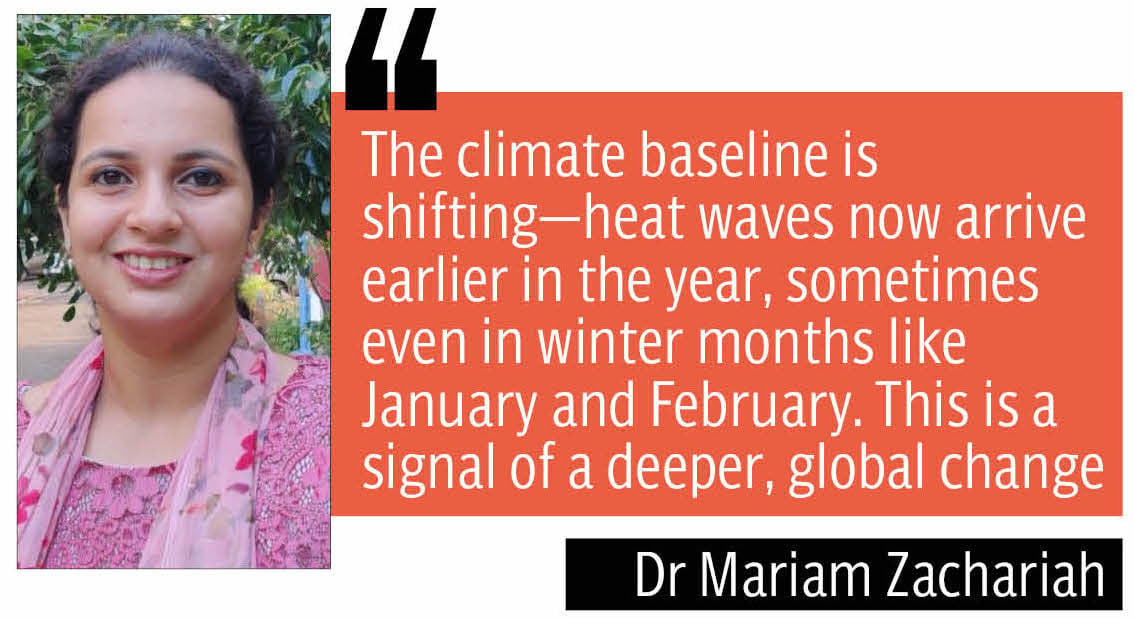

Record-breaking heat is no longer a once-a-decade anomaly – it is the emerging climate regime. “We are obviously seeing a lot more record-breaking events now,” said Dr Mariam Zachariah, a climate scientist affiliated with the Grantham Institute at Imperial College London. “This itself suggests we are approaching a new baseline.”

She explained that what was previously considered the peak heat season — mid-April to May — is now expanding. Reports of dangerously high temperatures emerging as early as January or February mark a shift not only in the climate but also in the expectations of what a season looks like. “You’re seeing early onsets of heatwaves,” she cautioned. “We also see seasons that are anomalously hot rather than discrete short heatwave spells. Nights are getting warmer, and the geographic extent of these events is widening.”

This recalibration has consequences far beyond meteorological charts. It draws a direct line between planetary changes and institutional strain — particularly in countries like Pakistan, where systemic vulnerabilities, not just exposure to extremes, compound the crisis.

Pressure on weak systems

“The problem isn’t just the temperature,” Zachariah said. “It’s poverty, inequality, displacement — all of that layered on top of fragile systems.” Informal housing, inconsistent power supply, inadequate emergency response, and an overstretched healthcare system combine to deepen the toll of each event.

These interlocking failures are not unique to Pakistan, she clarified, but part of a pattern across developing nations. “In overcrowded hospitals, something as basic as storing temperature-sensitive medicines becomes a challenge during heatwaves,” she said. “You add that to rising hospitalisations, limited staff, and overstretched supply chains — and the vulnerabilities multiply.”

Patchy data and fragmented planning

Zachariah pointed to a persistent problem in climate planning – the lack of fine-resolution, consistent data. “You often don’t have well-monitored, high-resolution datasets without gaps when it comes to measuring the impact of hazards,” she said. While gridded datasets are improving and perform reasonably well across South Asia, she noted that “real-time data from met offices isn’t always accessible,” especially in Pakistan.

The lack of actionable, granular data undermines the ability to anticipate and adapt — from heat action plans to targeted public health responses. “We need more research to improve infrastructure, and we also need to think about livelihood diversification,” she said.

Heatwaves are migrating

While Pakistan’s southern belt has long been on the frontlines of extreme heat, the geography of risk is shifting. “You can never say it’ll be limited to just the plains,” Zachariah said. “Every region is warming. That means even places that haven’t experienced heatwaves before are now reporting high-temperature events.” This trend is well-documented in attribution science, which confirms that climate change is not a far-off abstraction but a present, intensifying reality — and increasingly, a political one. Adaptation, she implied, cannot wait for catastrophe to force a reckoning. “How soon and how effectively we act determines not just the damage but whether systems collapse under pressure.”

Beyond the new baseline

If Zachariah’s warning about the new baseline sounded urgent, Dr Zafar Imran's analysis pushes that alarm closer to existential. A non-resident research scholar at the Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland, Zafar describes a world where weather, once tethered to patterns, has broken loose into chaos. “The end of stationarity,” he explains, marks a fundamental rupture. The Holocene-era climate stability that underpinned modern civilization is fading fast, replaced by violent unpredictability – unseasonal downpours, parching droughts, and heatwaves that now arrive not as anomalies, but as fixtures.

Pakistan, he argues, is living through the “press and pulse” of climate change—a steady rise in baseline temperatures (the press) punctuated by severe, erratic shocks (the pulse). Yet, despite being among the most climate-vulnerable nations on Earth, Pakistan’s response has largely been to stumble from one calamity to the next. “At best,” says Imran, “we’ve been rolling with the punches.”

The country, he said, has no coherent long-term strategy for heat adaptation or risk reduction. “There’s no national early warning system designed to protect the poor, no coordinated plan that links health services to urban heat management, no binding policy that recognises extreme heat as a public health emergency. Heatwaves, like floods and droughts, are treated as episodic—disasters to survive, not signals to prepare.”

But this survivalist approach ignores a deeper truth. “Pakistan’s average annual temperature has already crossed the 1.5°C threshold,” Imran notes. In plain terms – the climate future that much of the world still considers avoidable is already Pakistan’s lived reality.

“What amplifies this danger is the compound effect of urbanisation and deforestation,” he warns. Yet, solutions exist. Imran points to urban greening as a key, cost-effective strategy to reduce heat stress. “Trees shade streets, cool air through evapotranspiration, and improve air quality,” he says. Cities like Lahore and Islamabad, which have seen tree-planting initiatives, offer hopeful examples. But these efforts need scale and coordination.

Importantly, these interventions must be equitable. The urban poor, often crowded in heat-exposed neighbourhoods, need the most protection. “Without social justice in climate action,” Imran warns, “the cycle of vulnerability deepens.”

The solution

Across Pakistan’s cities, the uneven patchwork of green space reveals urgent challenges and fragile opportunities. Data compiled by The Express Tribune shows that Lahore and Karachi — sprawling economic powerhouses — offer barely 5 to 7 per cent greenery, well below the World Health Organization’s recommended minimum of nine square metres per person. This shortfall intensifies urban heat islands, compounding the toll of ever more frequent bouts of blistering weather.

Islamabad’s greener avenues and parks show the dividends of foresight, yet even there, gaps in data reveal how patchy governance hampers effective planning. Smaller cities like Peshawar and Quetta face harsher realities — Peshawar’s green cover is a mere sliver, leaving residents exposed to rising environmental risks, while Quetta’s tentative greening efforts underscore a wider need for systematic urban assessments.

The solution, experts argue, lies in weaving green infrastructure into every corner of the urban fabric — from street trees to community gardens — ensuring that all citizens, not just the privileged few, can find respite. Pakistan’s green space crisis, they caution, is tightly entangled with unchecked urban expansion, weak municipal governance, and escalating climate threats.