Pakistan and India have only just stepped back from the brink of an all-out war, following a fierce exchange sparked by the brutal rampage in Pahalgam, in Indian Illegally Occupied Jammu and Kashmir (IIOJK) — a tragedy New Delhi was quick to lay at Islamabad’s door. India, in a show of muscular defiance, escalated tensions by launching a military misadventure against its proportionally smaller adversary, ignoring international calls for restraint. The risky gambit, however, ended in bruised pride. Now, as an uneasy ceasefire — brokered by US President Donald Trump — tentatively holds, the atmosphere remains tense. And amid a volley of hostile rhetoric, New Delhi is reportedly plotting further provocations, threatening to push the two nuclear-armed rivals once again to the edge.

In the wake of the April 22 attack in the heart of the occupied territory, and as part of its predictable playbook, New Delhi unleashed a flurry of knee-jerk measures targeting Islamabad — the most consequential of which was its decision to place the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) in abeyance. “Right after the attack, Prime Minister Narendra Modi turned to non-military measures: expelling defence attachés, revoking visas, suspending trade (what little exists), closing borders. Pakistan retaliated in kind — standard tit-for-tat. But the real escalation was India suspending the Indus Waters Treaty. That’s huge,” said Dr Claude Rakisits, a Canberra-based geo-strategic analyst.

Rakisits is right in his assessment. The Indian threat to suspend the Indus Waters Treaty — a decades-old water-sharing accord that has weathered three wars and repeated diplomatic lapses — is no minor reaction. It strikes at the heart of Pakistan’s agricultural lifeline and is tantamount, in Islamabad’s view, to weaponising water. The move has been denounced as a violation of international law, with Pakistan warning that any attempt to revoke the agreement would be regarded as an “act of war.” Why does this water-sharing pact matter so much?

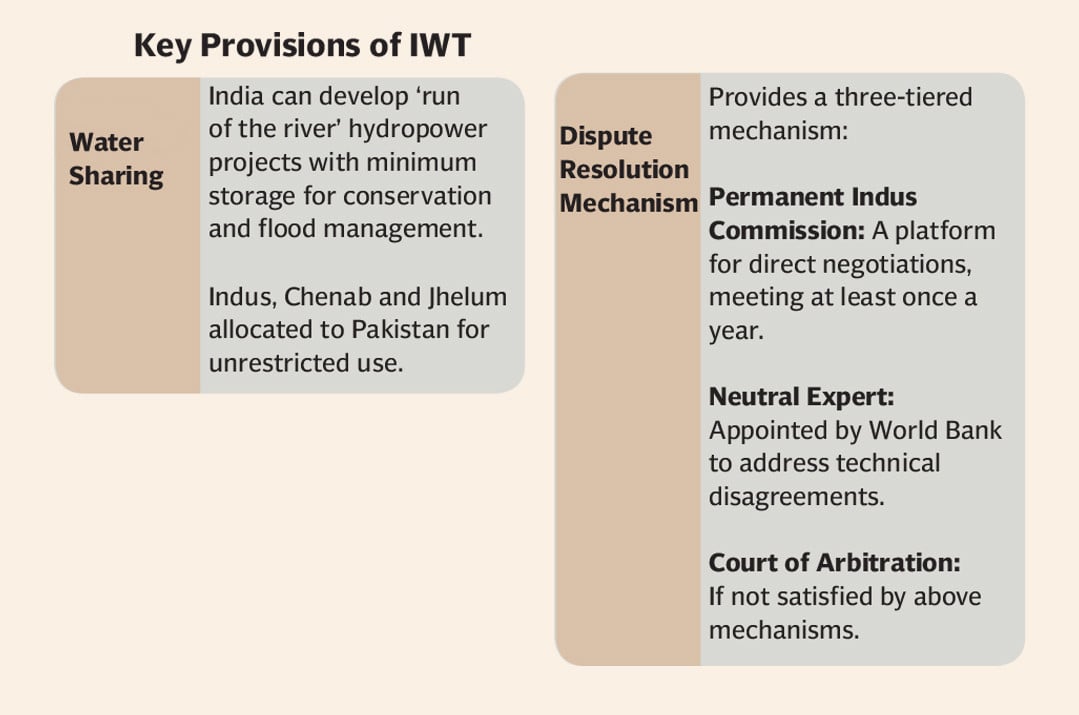

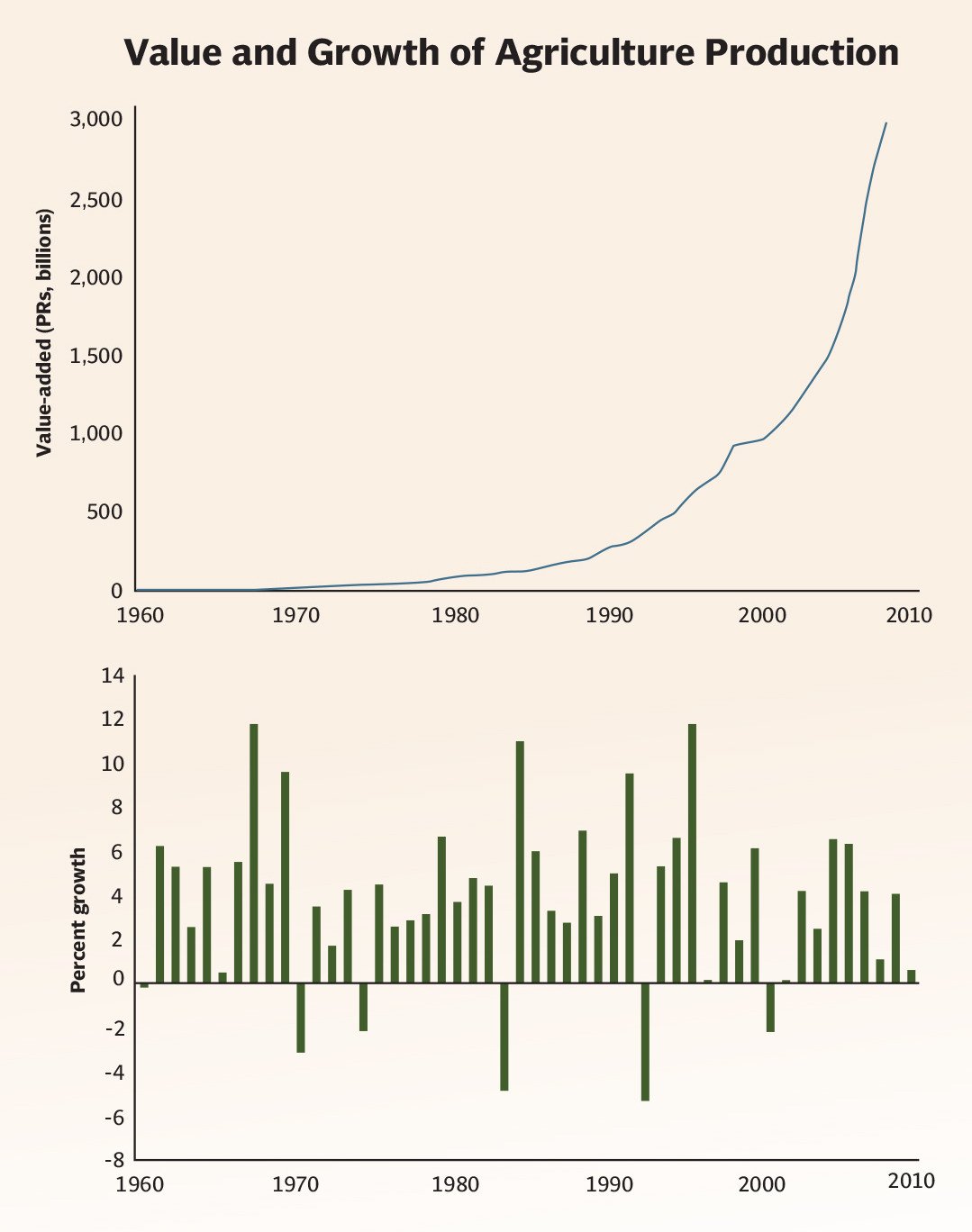

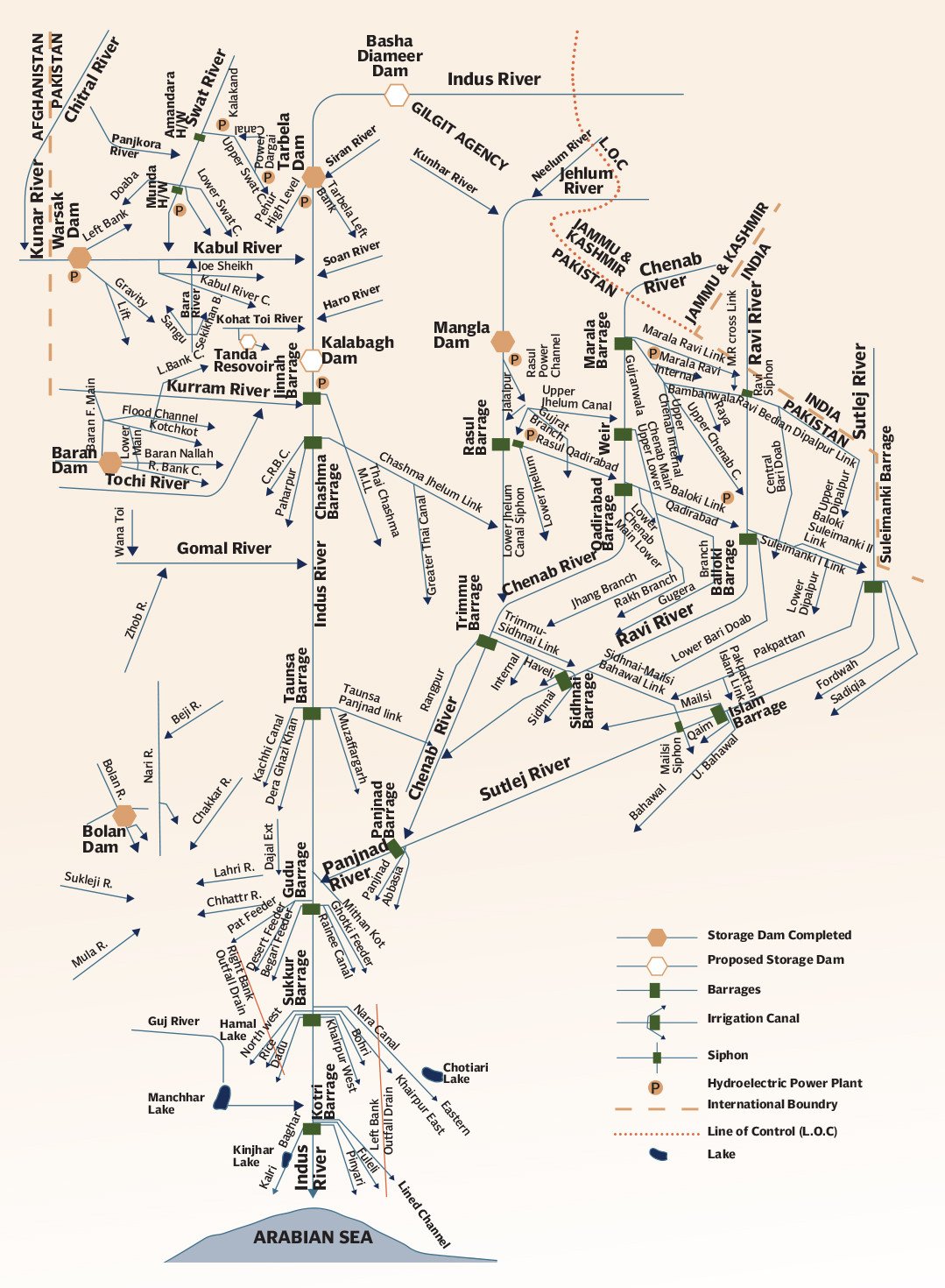

Briefly put, IWT is an agreement mediated by the World Bank between Pakistan and India in September 1960 to split usage rights of six major rivers – the Indus and its tributaries – between the two neighbours. India was granted the use of water from three eastern rivers – Sutlej, Beas and Ravi – while Pakistan was given most of the three western rivers – Indus, Jhelum and Chenab. The two sides have bickered over and disputed several projects on the Indus and its tributaries for years since the signing of the accord. Water from this river system is the lifeline of Pakistan’s agrarian economy as it feeds 80% of its irrigated agriculture – a sector which accounts for 24% of its GDP and employs around 37% of its workforce.

“India and Pakistan have fought multiple wars, but they’ve never touched this treaty. Now, for the first time, India is weaponising water. For Pakistan — where agriculture depends on these rivers — this is like holding a gun to its head,” said Dr Rakisits, who has been following South Asian issues for over 40 years. “This isn’t just aggressive; it’s potentially a violation of international humanitarian law. Pakistan is right to call it an act of war,” he added.

New Delhi appears to have started following through on its threat despite Pakistan’s warning. Indian officials told Reuters earlier this week that their country has initiated several measures that could affect the flow of water into Pakistan. “These include plans to double the length of the Ranbir Canal on the Chenab River, which would increase water diversion from 40 to 150 cubic meters per second. Moreover, India is considering the construction of new dams and hydropower projects on the rivers allocated to Pakistan under the IWT.”

Can India unilaterally revoke the treaty?

The short answer is no.

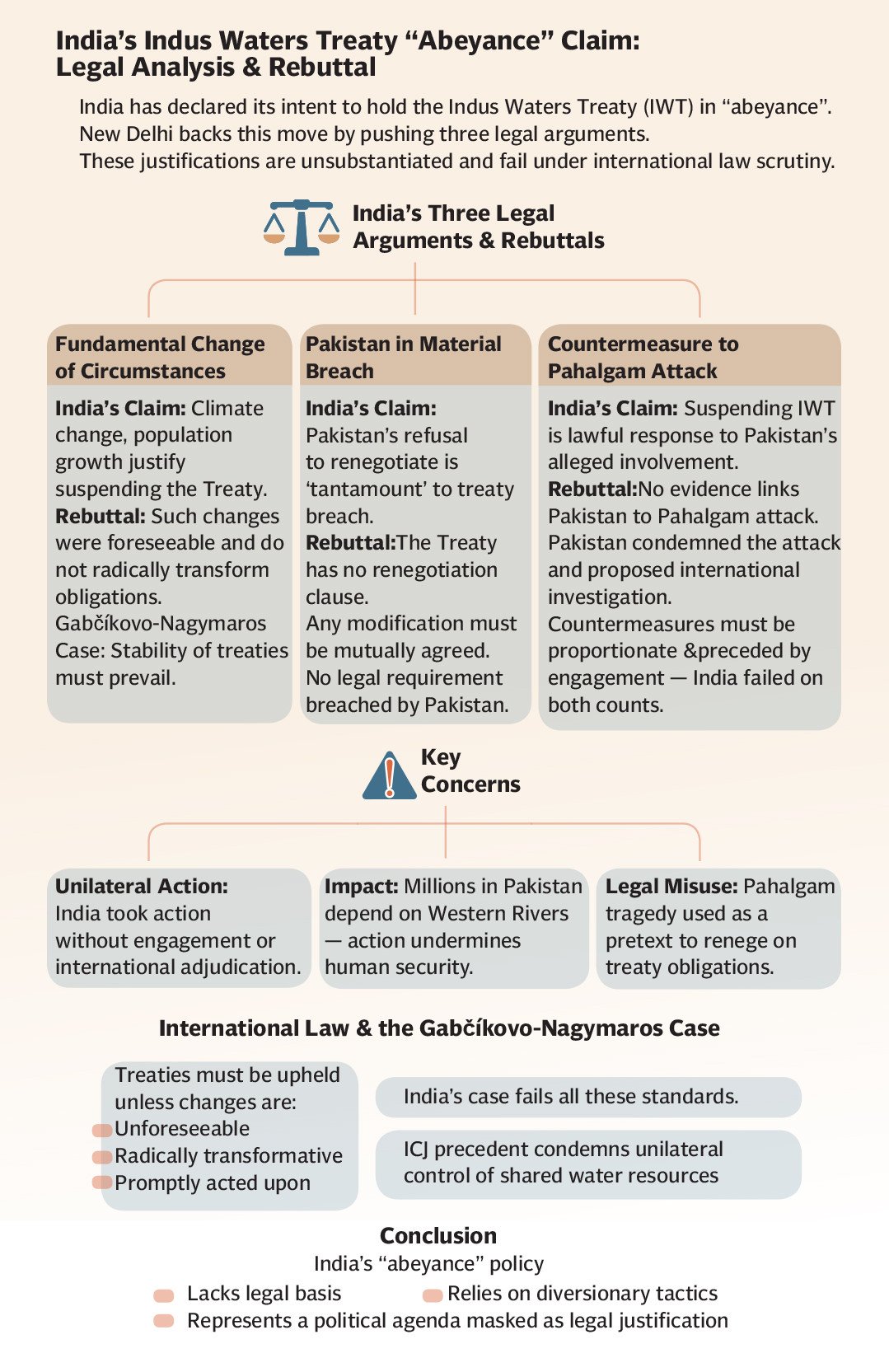

Legally, India cannot unilaterally withdraw from the IWT, as the agreement contains no explicit exit clause. Under international law — particularly the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (VCLT) — such a withdrawal or suspension is generally prohibited, unless prompted by a fundamental breach or a significant change in circumstances (rebus sic stantibus). Legal experts argue that Delhi’s move would violate both the treaty and customary international law. The fact that the accord has withstood multiple wars and periods of heightened tension further undermines any claim that current conditions justify its revocation.

The treaty’s own provisions reinforce this legal position. Article XII explicitly states that any modification to the agreement must be made by mutual consent. Similarly, Article IX outlines a formal dispute resolution mechanism, including the Permanent Indus Commission — which meets annually — as well as the option to refer technical matters to a Neutral Expert and broader disputes to a Court of Arbitration. India’s decision to place the treaty in ‘abeyance’ falls outside these established legal and procedural frameworks.

In fact, if anything, it was the World Bank chief who recently tutored the Modi government over its misstep. “There is no provision in the treaty to allow it to be suspended. The way the IWT was drawn up, it either needs to be gone, or it needs to be replaced by another one. That requires the two countries to want to agree,” World Bank President Ajay Banga said in an interview with Indian broadcaster CNBC-TV18. “The treaty is not suspended. It’s technically called something ‘in abeyance’ — that’s how the Indian government worded it,” he explained.

On this side of the border, former Indus waters commissioner Jamaat Ali Shah noted that Pakistan can invoke the treaty’s legal safeguards — and, if necessary, formally approach the World Bank, which serves as the guarantor of IWT. “Article VIII of this government-to-government agreement ensures that before any breach, the two sides will discuss issues at the level of the water commissioners. This is followed by engagement at the neutral expert level. If a legal dispute persists, the matter should then be referred to the Court of Arbitration,” Shah elaborated.

Banga clarified that the World Bank’s role is essentially that of a facilitator when disagreements arise — not to adjudicate, but to initiate the process of appointing a Neutral Expert or convening a Court of Arbitration. “Not by us making a decision,” he added, “but by us being the party that goes through a process to find a Neutral Expert or an arbitrator court to settle it.” The World Bank also covers the cost of this process through a trust fund established at the treaty’s inception to finance the fees of potential arbitrators.

Beyond the World Bank’s mechanisms, Pakistan also has other legal avenues to challenge India’s move. It could invoke Article 60 (material breach) or Article 62 (fundamental change of circumstances) of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties to escalate the matter to the International Court of Justice (ICJ). Alternatively, Islamabad might appeal to the United Nations, invoking principles such as “equitable water sharing” and the “prevention of transboundary harm” to press for international mediation.

“I see no reason why Pakistan should not immediately internationalise this,” said former national security adviser Moeed Yusuf. “We could potentially take the matter to the Court of Arbitration in accordance with the dispute resolution provisions of the IWT. Pakistan has to look at the other legal options too. Technically, the World Bank will be involved in forming the Court of Arbitration. We are also considering raising this matter at the UN Security Council,” he added.

However, each of these legal avenues presents its own challenges. The World Bank lacks any enforcement authority. The International Court of Justice has limited jurisdiction, as India does not recognise its compulsory jurisdiction in disputes involving Pakistan. The UN Security Council could be paralysed by a veto, with permanent members potentially blocking any meaningful action. Pakistan also cannot invoke the 1997 UN Convention on the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses, as it is not a signatory — though it may still cite its core principles, such as equitable utilisation and the prevention of significant harm, as part of customary international law. Even so, any unilateral suspension of the IWT risks damaging India’s international standing, as it would breach the principle of pacta sunt servanda — the foundational norm that treaties must be honoured.

There’s also a possibility of Pakistan leveraging its strategic relationship with China, especially as Beijing is not a party to IWT. China, which controls Tibet’s Indus headwaters, could use its own water projects on the Brahmaputra River (Yarlung Zangbo), which also flows into India and Bangladesh, as a tool. “India has made a mistake. They are also a middle riparian between China and Bangladesh. If they do this, they're going to open a can of worms. China already wants to build massively on the Brahmaputra River. I think they [the Indians] will very quickly have to backtrack and realise this is going to be detrimental to them,” said Yusuf.

The IWT suspension may not have an immediate impact, as India cannot restrict the flow of the Indus, Jhelum, and Chenab rivers due to insufficient storage capacity. However, it could carry out some diversions using existing facilities, such as the Kishenganga Dam — as it did in early May, when water at a key receiving point in Pakistan briefly dropped by as much as 90% after India reportedly began maintenance work on certain projects. Days later, there was an unusual surge in water flow in the Chenab River when India emptied the Kishenganga Dam, suggesting deliberate water management aimed at storing water for future use.

Though India at present doesn’t have enough storage capacity, it could in the short term – say one to two years – undertake several measures, such as desilting and making minor diversions, halt data sharing, block project inspections, and reduce hydropower coordination, while impact on Pakistan’s agriculture would emerge gradually. In the medium term, 3–5 years, it could accelerate work on disputed projects like the Shahpurkandi dam on the Ravi River and the Ujh multipurpose project on the Ujh River in IIOJK. In the long term, larger storage infrastructure — such as the Ratle hydropower project — could be developed, although any major impact on dry-season flows would take years to materialise.

In Yusuf’s opinion, Delhi used the Pahalgam pretext to do what it had long aspired to — suggesting a premeditated move, not a trigger-happy moment. “They [Indians] had been trying to make the IWT dysfunctional for a while. They wanted to carry out more construction on the eastern tributaries, some of which the IWT didn’t allow. They had also asked Pakistan to renegotiate the treaty in the recent past (within the last two years), but I think they seized this moment and perhaps used it as an excuse,” Yusuf added.

What should Pakistan do for its water security?

Given the longstanding tensions over IWT and India’s apparent ambitions regarding it, one might ask: why hadn’t Pakistan developed a contingency plan for its water security? “Water from these tributaries is our lifeline. There isn’t an easy contingency that can realistically offset this dependence. Contingencies work when a particular part of the body faces disruption, and you can bypass it somehow. But if your entire body is that part — in this case, water rights under the IWT — then what’s the bypass? It’s not a comfortable position for Pakistan to be in. That’s why it is so vital for the IWT to remain intact, both for Pakistan and for India,” explained Yusuf.

Experts now argue that Pakistan must ensure long-term water security in the presence of a neighbour that disregards all bilateral agreements and customary international laws. For this purpose, Pakistan should adopt a multi-pronged strategy: diversify its water sources by investing in reservoirs, groundwater management, and China Pakistan Economic Corridor-related infrastructure projects; enhance its legal framework by ratifying the UN Watercourses Convention; strengthen diplomatic alliances by leveraging support from China and the Islamic bloc; and implement internal reforms to curb agricultural water waste through modern techniques such as drip irrigation.

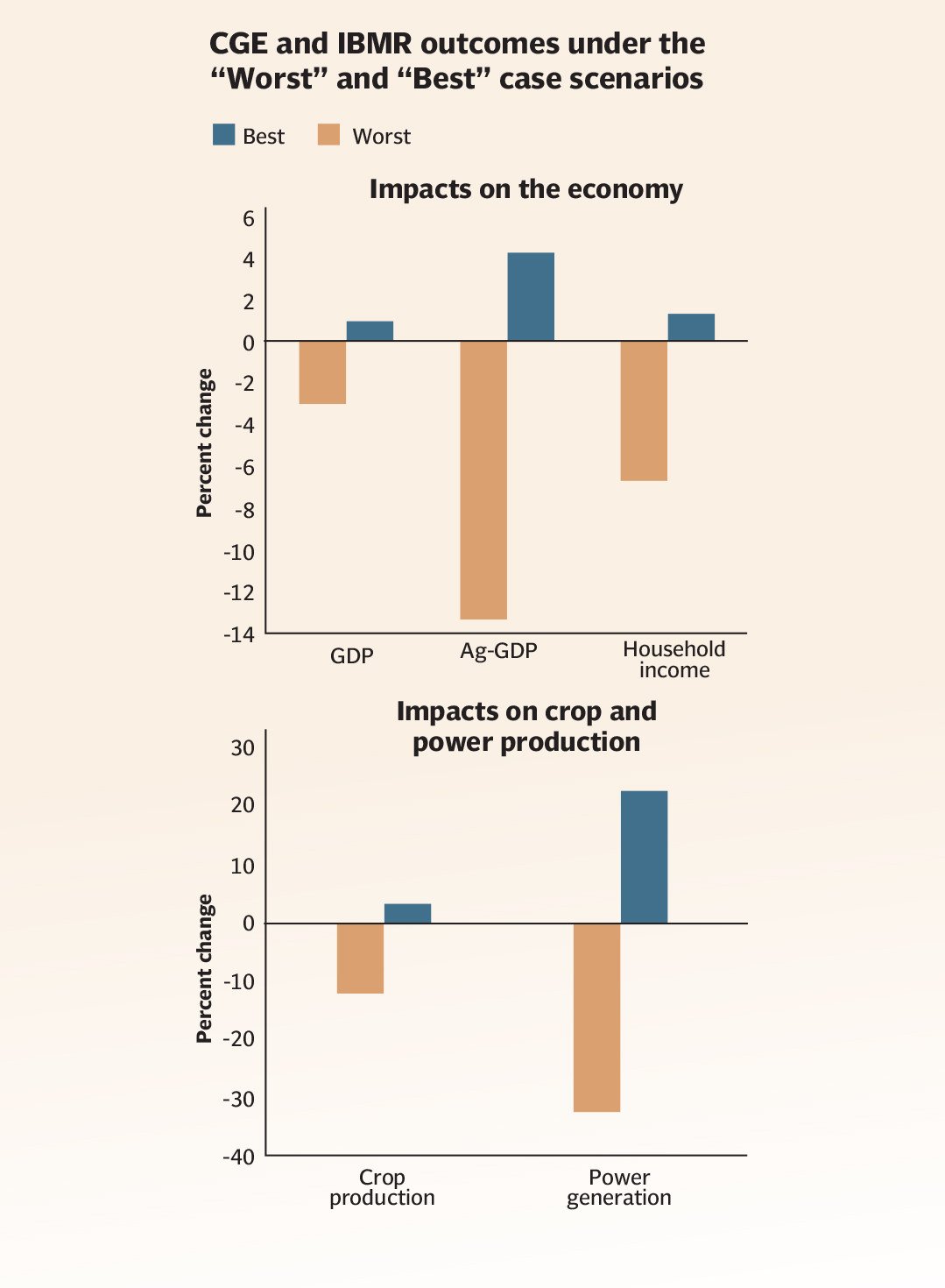

This urgency stems from the significant challenges India’s move could pose to Pakistan, particularly in the agriculture and energy sectors. Should water flows become erratic — especially during the dry season — the entire agricultural system would suffer, hitting irrigation-dependent crops such as wheat, rice, and sugarcane, and leading to massive economic losses. Similarly, the energy sector could be impacted; Tarbela Dam alone contributes nearly 30% of the country’s electricity through hydropower generation. Reduced water availability could diminish this capacity, worsening energy shortages. Moreover, water scarcity risks driving inflation, exacerbating food insecurity, and potentially fueling large-scale social unrest.

Yusuf traced India’s actions back to the ‘saffronisation’ shaping the country’s political landscape. “The real issue was that we had a neighbour driven by a supremacist Hindutva ideology that saw no problem with putting on hold a treaty that provides for 250 million people,” he said. “A country willing to accept — even boast about — starving 250 million people of their main water source shows how far a fascist ideology from the top can take a nation. But such a move would not just hurt Pakistan; it would cause chaos across the entire region.”

With its water lifeline under existential threat, Pakistan faces a battle for survival that demands more than diplomacy — it requires a full-spectrum response. Experts argue that Islamabad must adopt a multi-pronged strategy encompassing diplomatic engagement, legal arbitration, and infrastructure readiness to safeguard its water rights. Former Indus waters commissioner Jamaat Ali Shah, who has witnessed the dispute firsthand, warns that if India follows through on its threat, it will not only endanger Pakistan’s survival but also escalate tensions across the region. “Pakistan must impress upon the international community that India’s actions could push the region towards war,” he said. “If India diverts Pakistan’s share of water, it will amount to hydro warfare — and in such a case, Pakistan should strike back hard.”

But should all diplomatic and legal efforts have failed, and India proceeded with such hostile actions, defence experts have already raised the red flag -- a calibrated military response would have become inevitable to protect Pakistan’s vital national interests. And this would come as no surprise — Islamabad has declared unequivocally that any attempt by India to usurp or divert Pakistan’s share of water would have amounted to an “act of war” and would have been met with full force.

Outlining what such a response might entail, Maj Gen (retd) Inamul Haq said: “If all diplomatic avenues are exhausted, Pakistan may have to consider kinetic options. This could involve targeting specific components of Indian hydropower infrastructure, including spillways, powerhouses, and dams.” He acknowledged that such military action could be highly escalatory and risk provoking a strong retaliation. “However, a credible demonstration of Pakistan’s resolve is necessary to deter unilateral moves by India, because water is a matter of life and death for us.”

The stakes, experts warn, could hardly be higher. Should the Modi-led government choose to go rogue — flouting international law, rejecting neutral arbitration, and weaponising water against Pakistan — it would risk igniting a conflict with catastrophic consequences. The international community is aware that a war between two nuclear-armed rivals could swiftly spiral into an apocalypse, threatening not only South Asia but global peace and stability.