In the words of Caroline Dyer, the great grand-daughter of General Dyer. “General Dyer was a very honourable man and greatly liked by the Indian public. He spoke three or four Indian languages that very few people did.”

“I think we may be brushing over his contempt for Indians when we talk about the fact that he knew four languages and certainly your recollection or understanding of how he was received by Indians would certainly be at odds with what we understand and what is written about him,” are the contradictory words of Raj Kohli, whose great grand uncle was a survivor of the massacre. The above is from a Channel 4 documentary Indian Massacre – Relatives of Officer Responsible & Victim Meet. Caroline Dyer is credited as Relative of Officer Responsible and Raj Kohli is credited as Relative of Victim.

I recently saw a Channel 4 documentary, The Massacre That Shook The Empire, starring Caroline Dyer and Raj Kohli. According to a piece in The Guardian, “I believe,” says Sathnam Sanghera, the presenter, “the Amritsar massacre was the moment Britain lost its empire,” while Churchill said later that it was an isolated event in British rule – the fault, essentially, of one rogue senior officer, Reginald Dyer. Sanghera visits his great-granddaughter, Caroline – she has the look of an aged royal’s lady-in-waiting – to find out if his family live in eternal shame. She said the words quoted in the beginning of this piece.

As the world marks 106 years since the horrors committed at Jallianwala Bagh, it still remains chillingly relevant. In an age where state violence, censorship, and the weaponisation of fear are rampant tools of governance, revisiting this atrocity is just as much about remembering the past as it is about recognizing the present. The story of General Dyer is by all means, a cautionary tale: that unchecked authority, when fuelled by prejudice and paranoia, can turn any system into a machine of terror. It is only when we confront history, that we can sharpen our lens on the world today.

It was on the morning of Baisakhi in Punjab of British India; a Sunday on the 13th of April 1919, where under the searing Amritsar sun, a large crowd, numbering in the tens of thousands, gathered in the historic garden memorial of Jallianwala Bagh, to celebrate the harvest and upcoming spring.

It was there in the late afternoon, when the crowd “was at its densest,” that one General Reginald Edward Harry Dyer, without warning, commanded his troops to fire into the peaceful, unarmed civilian crowd of Hindu, Muslim, and Sikh men, women, the elderly, the young children and even babies.

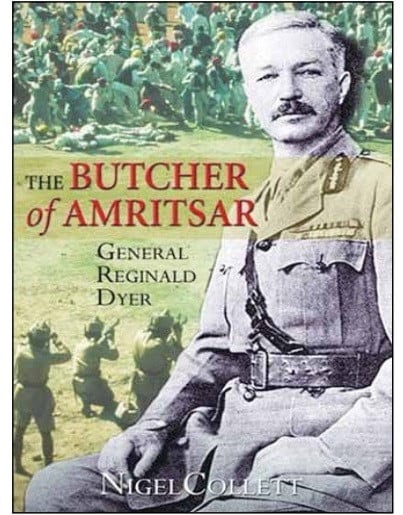

What ensued was not just a massacre, but a defining moment of moral collapse; a deliberate act, dripping with malice, that left at least, according to British Raj sources, 379 dead (various reports ascertain the toll to be around 1500) and over thousands were injured. It was there, as the blood seeped into the soil of Jallianwala Bagh, that imperial psyche stood unmasked, in one man — the man history would forever remember as the "Butcher of Amritsar."

Born in 1864 in Murree, Punjab, Dyer was, ironically, a son of the same soil, raised in colonial India, yet distinctively molded by British militarism. His education in Shimla, Cork, and Sandhurst planted in him the virtues of loyalty to the Crown and an intense suspicion of the ‘native mind’. When he assumed command in Punjab, he did so not just as a soldier but as a personification of Britain’s imperial anxiety.

For the British elite in India, the spectres of the 1857 mutiny still lingered. Any expression of Indian dissent, even peaceful, reeked to them of sedition. The Rowlatt Act, which curtailed civil liberties under the guise of national security, had already begun to fan the flames of anti-establishment sentiment. That fateful day, as Dyer witnessed from the ramparts, he did not simply see a crowd — he saw a mob, an insurrection in process, a very stark and cruel defiance of an ungrateful populace towards their dignified governance.

The truth in fact was far simpler, as the Hunter Commission confirmed: “The crowd were not armed rebels but local residents and villagers.”

What makes the events at Jallianwala Bagh possibly more sinister is Dyer’s own admission later. “I did not wish to disperse the crowd.” he said, “[It was] to punish the Indians for disobedience.” While he waited for the crowd to swell to its possible apex, he gave no indication of warning. Dyer ensured that all exits were blocked before he ordered his soldiers, handpicked Gurkha and Baloch riflemen, particularly known for their unwavering loyalty to the Crown, rallying them to fire into the heaviest sections of the crowd. The shooting continued for ten minutes, ceasing only when ammunition was almost depleted.

The Prime Minister of the United Kingdom at the time, Winston Churchill, speaking in the House of Commons, called it “monstrous.” Never short of words, he vividly painted the horror: “Pinned up in a narrow place…packed together so that one bullet would drive through three or four bodies…the fire was directed down on the ground.” No advocate of Indian nationalism, even Churchill recognised the severity of the catastrophe: “An episode without precedent or parallel in the modern history of the British Empire.”

Later when asked whether he would have used machine guns mounted on armoured cars, Dyer responded: “I think probably, yes.”

Dyer was not a rogue commander. He was the conclusion of imperial logic. In his own words, “There should be an eleventh commandment in India: “Thou shalt not agitate.” He believed Indians were incapable of self-rule, “Self-government for India is a horrible pretense,” he wrote. Even Mahatma Gandhi, he claimed, would lead the country into chaos.

He later admitted to the Hunter Commission: “I think it quite possible that I could have dispersed the crowd without firing but they would have come back again and laughed, and I would have made a fool of myself.” This wasn’t strategy — it was psychotic vanity, clothed in racial superiority. The goal had never been peace; it was subjugation and humiliation.

A day earlier, Dyer ordered Indians to crawl on all fours through a street where an Englishwoman had been assaulted, this was another manifestation of his dehumanizing behavior. “Indians crawl face downwards in front of their gods,” Dyer explained. “I wanted them to know that a British woman is as sacred as a Hindu god.” He backed this with public floggings and martial law.

Despite condemnation in British Parliament, the vote went 247 to 37 against him, Dyer had returned to Britain to a bizarre hero’s welcome. The conservative Morning Post raised over £26,000 in his honor, dubbing him “the man who saved India.” Rudyard Kipling, among others, donated to this fund. Meanwhile, Indian Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore renounced his knighthood in protest.

Tagore’s letter remains one of the most powerful indictments: “The time has come when badges of honour make our shame glaring in the incongruous context of humiliation.” Dyer’s act, and the failure to properly prosecute it, shattered any lingering illusions of British justice among Indians.

Dyer’s defense was always the same where he believed he was preempting a revolution. “I was confronted by a revolutionary army,” he claimed. But there was no such army. What existed was a wounded, angry people, demanding dignity in the twilight of war, inflation, and gross repression.

As with any ruthless persecution, the massacre’s legacy birthed further discord. Udham Singh, who, having witnessed the carnage as a child, would assassinate Michael O’Dwyer, Punjab’s former Lieutenant-Governor and Dyer’s greatest enabler, in London in 1940. Singh declared at his trial: “I did it because he deserved it. He wanted to crush the spirit of my people, so I have crushed him.” Singh’s execution turned him into a martyr. The massacre he avenged inspired Gandhi’s non-cooperation movement and irrevocably turned moderate nationalists into fierce anti-colonialists.

Today, bullet holes still scar the redbrick walls of Jallianwala Bagh. A plaque marks the Martyrs' Well, where many leapt to their deaths in desperation. Yet, over a century later, Britain still stops short of a formal apology. Prime Ministers have visited the site. Queen Elizabeth II herself bowed her head to it in 1997. David Cameron called the massacre “deeply shameful.” Theresa May called it “a shameful scar.” But no one ever said: “We are sorry.”

In 2019, Sadiq Khan the Mayor of London, urged Britain to apologise. “This is about properly acknowledging what happened.” he said. But perhaps the reluctance to apologise stems from what a real apology would reasonably demand: a reckoning.

To truly apologise, Britain would need to acknowledge that Jallianwala Bagh was not a deviation from the empire — it was in actuality, its essence. Dyer was not a monster but an agent. His actions were not “un-British,” as the Hunter Commission claimed but as history shows us, profoundly imperial.

A decade shy of the carnage, Reginald Dyer breathed his last in 1927, plagued by strokes and reportedly haunted by self-doubt. A God-fearing man “I only want to die and know from my Maker whether I did right or wrong,” he said on his deathbed. Perhaps uncertainty was his only punishment. But for the Indian subcontinent, the punishment was generational, a wound carved by bullets and sealed by denial.

Dyer’s character, as repugnantly revealed, forces a difficult truth upon us. He was not just one man with a rifle and a rank. Dyer was a proxy of a system, one that believes that one can rule through fear, a system that knows that some lives matter more than others, and a system that perpetuates, that the dignity of a nation can be extinguished by imperial pride.

The Jallianwala Bagh Massacre was an example of an Empire speaking plainly: obey, or bleed.

And it was from that day forth, any chance of a united India burned away. The long-oppressed citizens would no longer seek a truce; they would demand their freedom.

All facts and information are the sole responsibility of the writer

The writer is a PR and communications strategist, cultural curator and director of communications at Media Matters