At the crowded emergency ward of a public hospital in Karachi, 18-year-old Areeba* clutched her mother’s hand as they waited for their turn. The room buzzed with hurried voices, beeping monitors, and doctors calling out names. But for Areeba, the world remained quiet. Not metaphorically, literally.

Born deaf, Areeba had learned to read lips and express herself through sign language. But none of that mattered here. The nurse behind the counter kept shouting her name, mispronouncing it, unaware she couldn’t hear. Her mother tried to explain, fumbling with words she didn’t have the training for. Areeba’s gestures grew more frantic. The doctor, pressed for time, glanced up and muttered, “Why doesn’t she speak? Bring someone else.”

This is the daily reality for thousands of Pakistanis deaf or hard of hearing, navigating a world not built for them. A world that demands speech and sound to acknowledge existence. One where access to basic rights, education, healthcare, employment, hinges on a voice they don’t have, and an understanding society refuses to develop.

And yet, the silence they live in isn’t just theirs. It belongs to a system that’s quiet on inclusion. To institutions that still don’t recognise Pakistan Sign Language (PSL) officially. To schools without trained teachers, banks without interpreters, and buses with conductors who wave them off because they can’t speak back.

But within this silence, voices are beginning to rise, not in volume, but in visibility. Through innovative tech, grassroots movements, and inclusive policies being pushed by private and non-governmental organisations, the deaf community is finally being heard, even if not always understood.

The silent struggle

Imagine standing outside your child’s classroom. You hear the school bell ring, but they don’t move. Everyone else picks up their bags and runs out, laughing. Your child just sits there, waiting for a signal only they can understand, one that may never come.

That’s how Saba* describes the first few weeks of school for her son Daniyal*, who was born deaf. “He used to just sit and stare at the teacher’s mouth. He thought if he stared hard enough, he might understand,” she says, wiping her glasses with the edge of her dupatta. “But no one in the classroom, including the teacher, knew any sign language. And no one tried to learn.”

It’s these invisible barriers, the ones that don’t make headlines that quietly shut the door on millions of deaf Pakistanis every day.

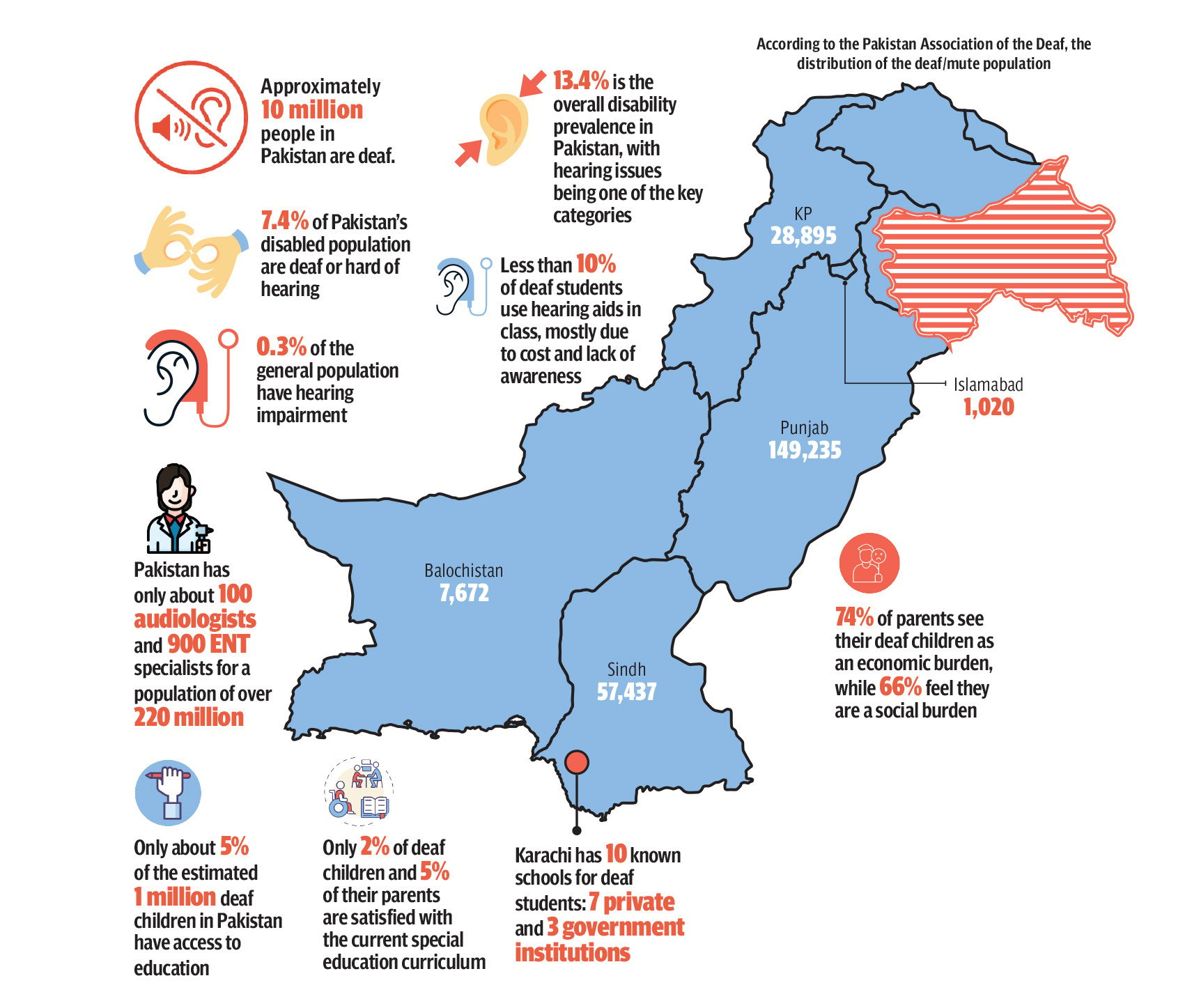

There are over 1 million deaf children in Pakistan, but less than 5% of them are enrolled in schools. The numbers are even worse for girls. The few who do get admitted often sit through years of schooling without truly understanding a word.

“It’s not about intelligence. It’s about access,” says Sakina a trained sign language expert. “We are setting up deaf students to fail by denying them trained teachers, interpreters, or even visual-friendly content. It’s like asking someone to run with their feet tied.”

This isn’t just a Pakistani problem; globally it’s a neglected population. The World Federation of the Deaf (WFD) estimates 80% of deaf people worldwide have no access to education in their preferred language. That ‘language’ is usually sign language, something Pakistan still hasn’t legally recognised.

Education is just one wall in a maze of silence. Healthcare is another.

Zahid Siddiqui, a 24-year-old from Lahore, told The Express Tribune through text about his experience when he showed up at an emergency room with severe stomach pain. The nurse kept asking him questions he couldn’t answer. He tried writing on paper, pointing to his abdomen, even miming pain. After a long wait, they gave him painkillers and sent him home. Two days later, he was diagnosed with a ruptured appendix, too late for a simple fix.

There are no certified medical sign language interpreters in most hospitals in Pakistan. While apps like ConnectHear and DeafTawk have started providing on-demand interpretation via smartphones, public hospitals rarely have Internet, let alone the infrastructure to support such services.

Employment? That’s another wall. Most job listings don’t even consider deaf applicants. For the few who do manage to get a job, communication remains a daily battle.

“I had to leave three different workplaces,” Faizan Saleem, a deaf graphic designer based in Karachi, told The Express Tribune with the help of a Sign Language Interpreter. “No one wanted to include me in meetings. They assumed I didn’t understand business. But I just didn’t understand them.”

He pauses for a moment before adding what stings the most. “Although we don’t have the hearing and speaking ability, our other senses are strong. But to communicate what is in our mind, the fastest way is to use sign language. I haven’t seen any workplace where the employees know sign language or even try to learn. This shows how much importance they give to us. I feel like keeping me at a job is a compulsion, not a need.”

Without government incentives or inclusive hiring policies, private companies have little motivation to adapt. Pakistan doesn’t have a national strategy for deaf inclusion. PSL is not officially recognised, meaning there's no standardisation, no government funding and no requirement for its use in schools or public institutions.

These are not just inconveniences. They are daily violations of dignity, opportunity and the basic right to be understood.

The first barrier

In a quiet home on the outskirts of Gujrat, five-year-old Ayaan sits in front of the television, his eyes fixed on the screen. The room echoes with the playful chaos of cartoons, but Ayaan doesn’t laugh. He simply watches, still and silent. His mother sits beside him, watching him more than the TV.

“He wouldn’t turn his head when we called his name,” she says, her voice low, not from shame but memory. “At first, we thought maybe he was just in his own world. We didn’t know it was because he couldn’t hear us.”

Ayaan's story is painfully familiar. Around 1.2 out of every 1,000 children are born with moderate to profound hearing loss in Pakistan, according to the World Health Organisation. Despite these numbers, there is still no national policy for mandatory hearing tests for newborns. Which means countless children, like Ayaan, are diagnosed late, if at all.

By the time a diagnosis comes, critical time has already slipped away. Language development slows. Social confidence suffers. Parents are left piecing together solutions in a system that offers little guidance and even less support. "If someone had told us earlier," Ayaan’s mother says, “maybe we could’ve helped him sooner.”

Over a million school-aged children in Pakistan are deaf, but fewer than 5% of them are enrolled in formal education. For girls, the barriers are even higher, layered with the weight of social expectations and limited mobility.

Organisations like the Family Educational Services Foundation (FESF) are trying to catch those falling through the cracks. Their Deaf Reach schools provide education and vocational training to more than 1,500 deaf children and young adults across the country. But even they know they can’t do it alone.

“We need the government to recognise PSL officially,” says a teacher at one such school. Without that recognition, there’s no mandate to include it in the national curriculum, no funding for training teachers and no systemic way to ensure deaf children learn in a language they understand.

Globally, the situation isn't much better – WFD estimates that 80% of the world’s 70 million deaf people have no access to education. The problem isn’t just resources. It’s will.

Every week, Ayaan and his mother travel 50km to Gujranwala, where he attends a special class at the National Institute for the Deaf. It’s a long journey for a short class, but it’s one of the few places where he isn’t treated like an afterthought.

“He’s learning to sign now,” his mother says with a cautious smile. “For the first time, he can tell me when he’s hungry. When he’s tired. It’s small, but it feels big.”

When the right tool speaks your language

For a long time in Pakistan, the deaf community has lived in the shadows of silence. But that is changing, slowly but surely, through the power of technology and the tireless work of those who’ve lived the silence themselves.

“ConnectHear directly tackles the severe communication gap faced by Pakistan’s Deaf community through a mobile application connecting users instantly to professional sign language interpreters,” says Arhum Ishtiaq, Co-founder and CTO of ConnectHear. “Since 2020, our platform has empowered governments, businesses, and individuals across Pakistan by making sign language interpretation readily available on smartphones.”

The team has developed what they claim is the world’s first real-time sign language recognition system, though it currently requires stable Internet and specialised hardware. Their efforts also extend to emergency preparedness.

“We recognised the urgent humanitarian challenge faced by the deaf community during disasters, where critical emergency alerts remain inaccessible due to communication barriers. Our experiences during COVID-19 highlighted that deaf individuals suffered disproportionately due to a lack of accessible information, resulting in isolation and vulnerability,” Arhum explains.

In response, the organisation launched an AI-powered disaster preparedness initiative in collaboration with Ufone and HANDS, with funding from GSMA. “This initiative ensures critical alerts reach deaf individuals effectively, bridging the existing accessibility gap during crises.”

“Our initiative significantly enhances disaster preparedness by optimising our virtual interpretation app to reliably function under harsh conditions, including low network quality and basic smartphone usage scenarios. Moreover, we employ AI to automatically convert disaster alerts into sign language videos, facilitating easy dissemination of life-saving information,” he adds.

ConnectHear’s multi-layered approach merges innovation with empathy, according to Arhum. “This dual approach ensures proactive preparedness through accessible, AI-generated information and reactive responsiveness via interpreter support, thereby substantially improving crisis resilience for deaf individuals and internally displaced persons (IDPs) with hearing impairments.”

Beyond emergency support, ConnectHear continues to tackle structural exclusion. “Deaf individuals in Pakistan face severe communication barriers, isolation during emergencies, limited educational and employment opportunities, and significant exclusion from essential services like healthcare and banking. The scale of these challenges is amplified by Pakistan’s lack of widespread awareness about sign language and limited infrastructure for Deaf accessibility.”

To overcome that, the organisation partners with banks, government offices, and telecom providers. “We actively partner with major institutions like banks, governmental organisations, and telecom companies to integrate our technology, creating environments where Deaf individuals can comfortably and confidently navigate public and private services,” says Arhum.

He’s also vocal about what systemic changes are needed, “Officially recognising PSL as a national language is fundamental. Public institutions should receive mandatory training on basic sign language and sensitivity training. Infrastructure improvements must include captioning and visual aids. Deaf individuals should be actively included in policy-making processes.”

“In Pakistan, there’s enormous untapped potential among deaf individuals, particularly within fields such as technology, digital media, entrepreneurship, and education,” Arhum added. “We actively train Deaf individuals in digital skills such as content creation, video production, digital marketing, and technology development.”

Meanwhile, DeafTawk, a tech startup born out of lived experience, has been breaking barriers of its own. “DeafTawk is a purpose-driven startup founded by three individuals from within the disability community, Wamiq, the first deaf engineer in Pakistan who graduated from the United States, and Ali and AQ, both of whom are blind. We didn’t just start a company; we built a movement rooted in our lived experiences,” says Ali Shabbar, Founder and CEO of DeafTawk.

“In Pakistan, over 9 million people are deaf or hard of hearing, and many cannot read or write due to a lack of inclusive education. For them, sign language isn’t just a tool; it’s their only language. DeafTawk bridges the communication gap through a digital platform that provides real-time access to certified sign language interpreters via a mobile app.”

With the help of DeafTawk’s 24/7 interpretation service, deaf users are rewriting their lives.

“With our mobile app and AI-based solutions, we’ve opened up a new world. Now, a deaf person can walk into a hospital and speak to a doctor via a remote interpreter in minutes. Students can attend online classes with interpretation support. Job seekers can communicate directly with employers. For the first time, technology has given the deaf community a tool they truly own, one designed in their language, for their needs,” Ali shared. He added that DeafTawk is now pioneering Pakistan’s first AI-based text-and-voice to sign language translation engine, designed to make education, public services, and digital content instantly accessible to the deaf.

According to Ali, DeafTawk has served over 97,000 deaf beneficiaries, provided over 2,000 jobs to sign language interpreters, and supported 1,200 deaf individuals in gaining employment to date. “We’ve also helped 1,500 deaf students enroll in higher education and made 75-plus organisations inclusive by integrating our interpretation services,” he said.

He shared the example of Kamran Lashari, the head of the Pakistan Youth Federation of Deaf & Hard of Hearing, who secured a prominent position in the technology department at COMSATS. “Deaf from birth, Kamran struggled to showcase his talent in traditional interviews. But with DeafTawk's interpreter services, he was finally able to communicate his skills clearly to the management. Today, he leads a team of 15 people and is one of the most valued professionals in his department,” Ali said.

Another inspiring example is Aliza Munim, a gifted artist from Karachi. Despite her talent, she found it hard to interact with customers and run her art gallery. With the help of DeafTawk, she now independently manages her gallery and communicates confidently with clients, breaking every barrier that once held her back.

And then, there are moments that redefine what technology truly means. “A few months ago, a mother walked into our office, her eyes full of tears. Her son, Kashan, is deaf, and for 31 long years, she had never truly understood him. With the help of DeafTawk’s interpreters, for the very first time, she had a full, meaningful conversation with her son. No statistics or success metrics can capture the weight of that moment. It wasn’t just about communication, it was about love, connection, and decades of silence finally being broken,” shared Ali.

When representation becomes responsibility

While startups like ConnectHear and DeafTawk have pioneered tech-led accessibility, some corporations are starting to rewrite the rulebook on inclusion. One of those few institutions in Pakistan’s corporate landscape is Standard Chartered (SC) Bank Pakistan.

For many deaf and differently-abled individuals, stepping into a bank branch can feel like stepping into a world that doesn’t speak their language. SC is changing that. They’ve launched ConnectHear’s virtual sign language translation application across select branches, ensuring that deaf customers are supported without needing a family member to interpret their needs. Sign language training is ongoing across all customer touchpoints, with the goal of having at least one trained colleague at every branch.

The bank has also prioritised inclusive design. It was the first in the country to introduce Braille banking forms and is working to ensure wheelchair accessibility at all its branches. Select locations have been upgraded as model branches that go beyond minimum regulatory requirements to accommodate differently-abled clients.

In 2023, SC sponsored ConnectHear’s largest career fair for differently-abled job seekers, connecting over 1200 candidates with 30+ prospective employers across 10+ industries. The bank has been equally active in convening the wider industry. They initiated the first-ever roundtable for banking industry HR heads to promote disability-confident hiring practices.

Other institutions are beginning to follow suit. Unilever Pakistan has conducted disability confidence workshops and begun hiring through inclusive pipelines. Jazz and Telenor have partnered with DeafTawk for customer service inclusion. Mobilink Microfinance Bank has rolled out a digital literacy initiative tailored for persons with disabilities.

Listening beyond words

For all the progress being made, life for many deaf Pakistanis remains a daily negotiation with a world that wasn’t built for them. What we need now isn’t just more technology. We need more humanity. Not just innovation, but intention. True change starts by accepting that communication is not a luxury, it’s a right.

First, PSL must be officially recognised as a national language. Second, our infrastructure needs to reflect real inclusion. Accessibility should be built in, not bolted on. Third, we need to move from token hiring to true inclusion. Setting quotas means little if workplaces aren’t equipped to support deaf professionals.

Representation needs to be real, not just symbolic. Inclusion can’t stop at a billboard or campaign. Deaf voices need to be part of the conversation, not just translated, but truly heard.

And finally, we have to shift from helping to partnering. Deaf individuals aren’t people to be rescued, they’re people to be included. Every policy, program, and product meant to serve the community should be designed with them, not for them.

The system needs to change, but so does the lens we use to look at the deaf community. Because when we finally learn to listen, not just with our ears, but with empathy, we’ll realise that there’s a whole world of brilliance that’s been speaking all along. Maybe then, silence won’t feel so lonely.

*Names have been changed to protect identity