Every morning, Rehan, a 28-year-old software engineer from Karachi, scrolls through TikTok while waiting for his Careem ride to work. It’s become a bit of a routine, quick laughs, trending music, maybe a recipe hack or two. What Rehan doesn’t think about is the invisible thread connecting all of it: artificial intelligence.

TikTok’s algorithm knows what he likes before even he does. His ride is matched based on real-time data. Traffic predictions, route optimisation, payment verification, there’s AI at work behind every tap and swipe. Even the music his Careem driver plays on Spotify is influenced by machine learning.

By the time Rehan’s day ends, he’s interacted with AI a dozen times without ever calling it that. To him, it’s just “how things work now.”

And yet, for most Pakistanis, artificial intelligence still feels like something out of a movie, robot waiters, flying cars, or something Elon Musk is cooking up. It doesn’t seem real. It’s not part of dinner table conversations, government pressers, or schoolbooks. But here’s the thing: AI isn’t waiting for anyone to catch up.

Across the region, countries are moving fast. India is using AI to predict crop failures and improve classroom learning. China is building entire smart cities with AI at their core. Bangladesh is training young people in AI, robotics, and data science under its Vision 2041 plan.

And then there's Pakistan.

A country full of young, ambitious minds, one of the fastest-growing freelance communities in the world, and a tech adoption rate that surprises even global platforms, but with no national AI policy, no proper AI education at school level, and no meaningful government investment in this space.

Yes, there are sparks here and there. A few good university departments. Private training initiatives like Saylani, Panacloud, and some bootcamps. But there’s no real fire. No big-picture thinking. No urgency.

And the risk? It’s not just falling behind in tech. It’s being locked out of the future. While the world builds with AI, we’re still figuring out if we should bother teaching it.

Let talk about where the world is heading, where Pakistan stands, and what it will take to stop being just a user of AI tools and start becoming a creator in the global AI game.

Who’s winning the global AI race?

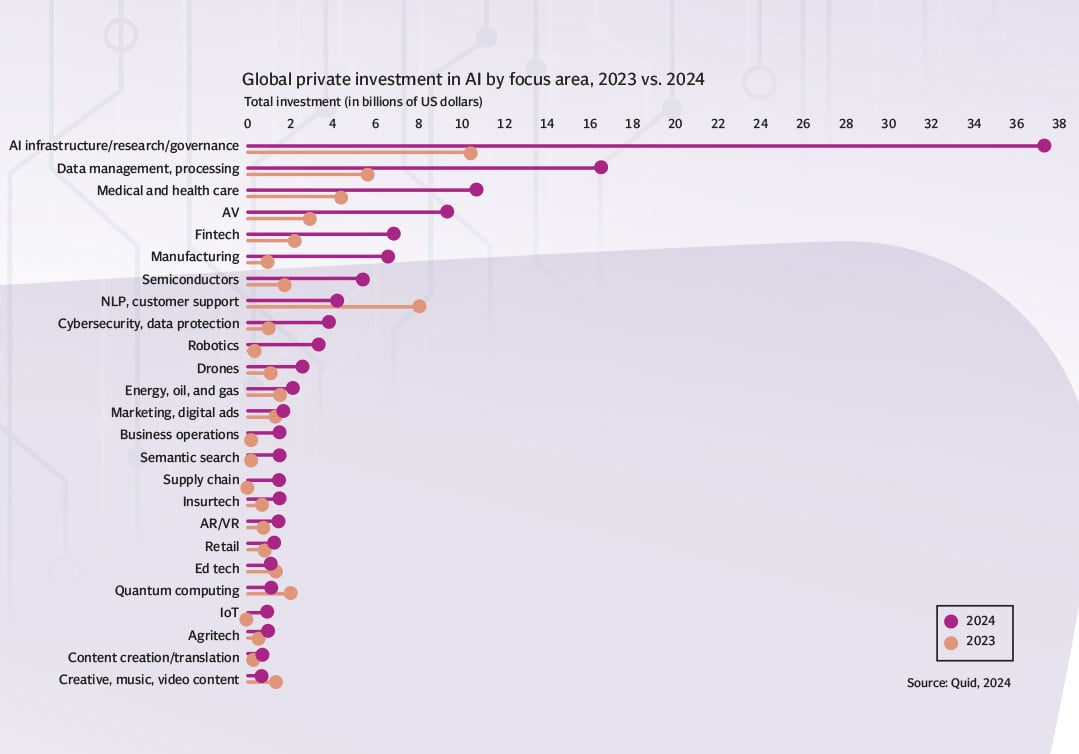

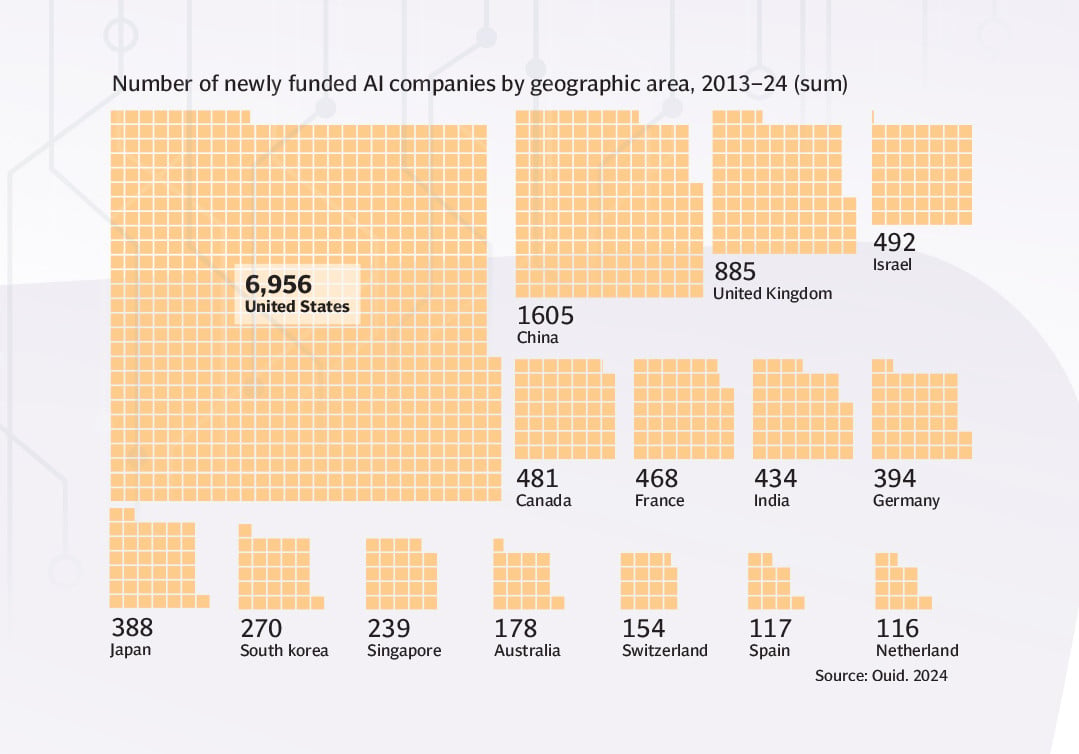

In 2024 alone, private investment in artificial intelligence around the world hit a jaw-dropping $252 billion. Leading the charge was the United States, which pumped in $109 billion, the highest by any country. That’s a 160 per cent jump from just a year ago, according to the AI Index Report 2025 by Stanford’s Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence (HAI) lab. The message is loud and clear: AI isn’t just a cool tech trend anymore, it’s being treated like the next industrial revolution.

Governments are baking AI into economic policy. Militaries are building around it. Corporations are racing to integrate it into everything from customer service to courtroom decisions. The same report reveals that more than 78 per cent of companies globally are now using at least one AI tool, up from 55 per cent in 2021. Whether it’s chatbots, virtual assistants, hiring tools, or fraud detectors, AI is running behind the scenes more than we realise.

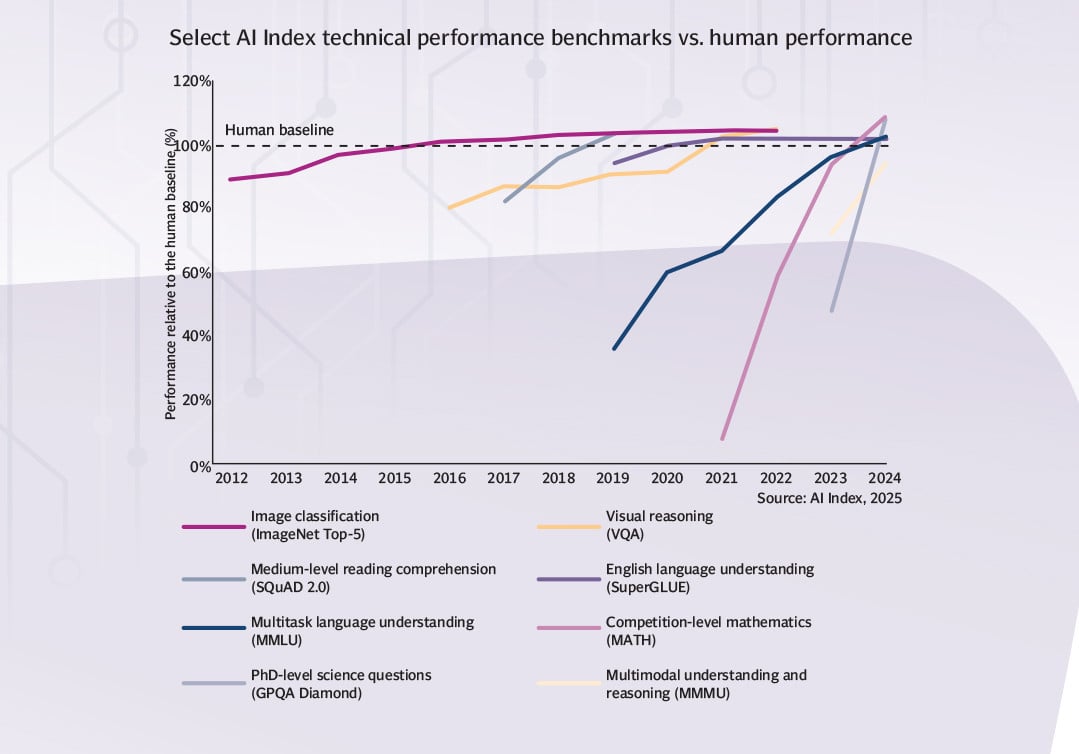

Generative AI, the tech behind viral tools like ChatGPT, Midjourney, and GitHub Copilot, completely took over the spotlight between 2023 and 2024. Investment in this space alone crossed $33.9 billion, that’s 10 times more than what was spent in 2020. These models can now outperform humans in writing, reading comprehension, coding, and even creating art. They’re reshaping industries like journalism, education, product design, and digital marketing at lightning speed.

Even the cost of running AI is crashing. Since 2020, it’s gotten 280 times cheaper to deploy models, which means adoption is about to explode even more, but only for countries that already have the infrastructure, cloud power, and skilled talent to handle it.

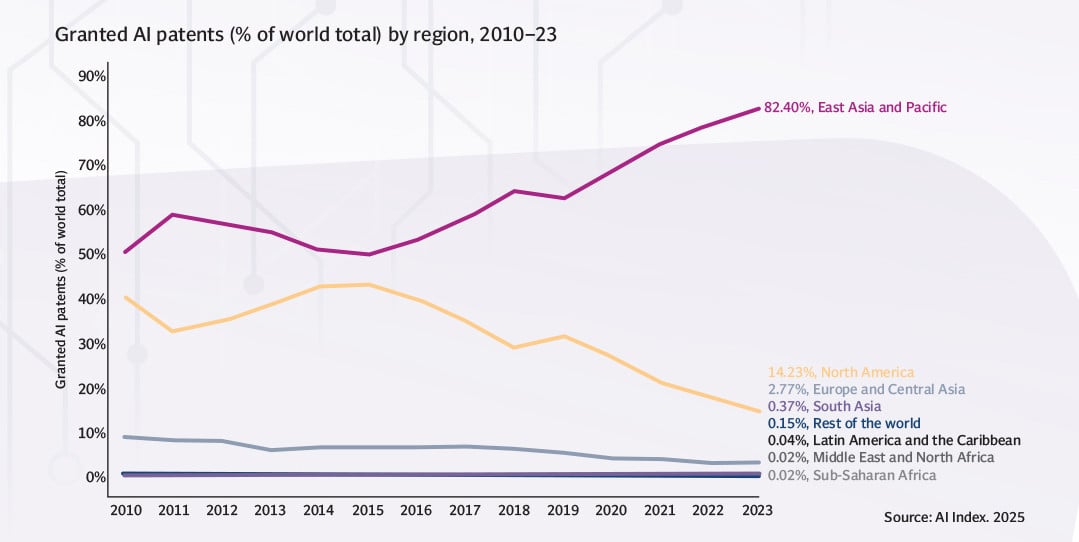

China isn’t just participating, it’s dominating. The country leads in AI patents (nearly 70 per cent) and publishes the most research globally. It has government-funded labs, AI-powered cities, and a 2030 vision to become the world’s AI superpower.

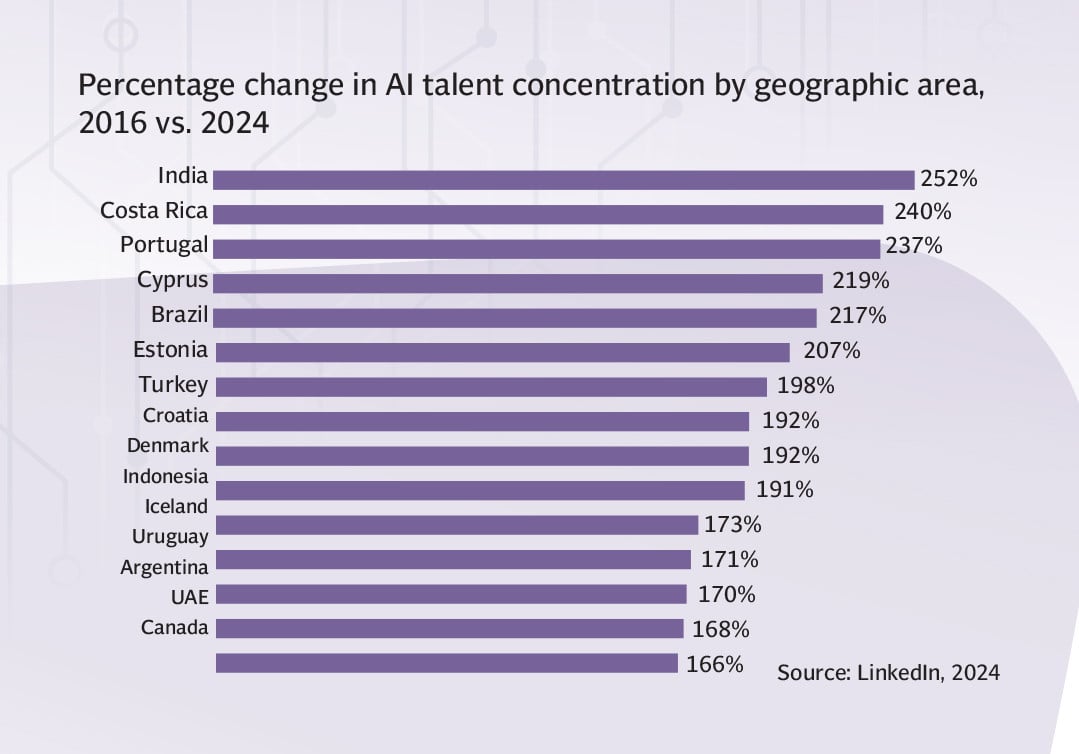

India, on the other hand, is climbing fast. With its $1.25 billion IndiaAI mission, it’s using AI to improve healthcare, agriculture, and digital services in over 22 local languages. The Stanford report actually praises India for thinking ahead, investing in skills, pushing policies, and building public-private partnerships to make AI part of daily life.

Even Bangladesh has started embedding AI into its long-term digital plan, focusing on upskilling and modernising government services.

And Pakistan?

Nowhere in the report. No shoutout in the investment charts. No presence in the education benchmarks. No mention in global research metrics.

While our neighbours double down, we’re not even at the starting line. And in a race like this, standing still doesn’t just mean falling behind, it means disappearing from the conversation entirely.

Where Pakistan stands

While the world’s powerhouses continue pushing the boundaries of artificial intelligence, reimagining how governments work and how economies grow, Pakistan is still figuring out where to start. There’s no national blueprint, no serious public investment, and whatever AI adoption we do see is scattered across sectors, often driven by isolated pockets of ambition rather than coordinated planning.

Still, a few sparks are visible. And if scaled right, they offer a glimpse of what could be possible. AI in practice or mostly on paper

Pakistan’s public health system hasn’t exactly welcomed AI with open arms. Most hospitals still run on manual systems, underfunded and overstretched. But some players in the private sector are beginning to test the waters. Startups like Sehat Kahani and xpertFlow are using AI for things like telehealth triage, while some hospital chains are experimenting with AI-assisted imaging for disease detection. Globally, we’ve already seen AI being used to detect cancers and speed up diagnoses; China and the U.S. are years into this game. For Pakistan, though, scaling these tools beyond pilot projects remains a distant goal.

AI in classrooms? Still rare. But again, a few efforts stand out. Platforms like the Sabaq Foundation and Noon Academy Pakistan use basic AI to personalise lessons. On the training front, Saylani Welfare Trust and PIAIC (Presidential Initiative for Artificial Intelligence & Cloud Computing) are building digital skills in AI, blockchain, and data science for thousands of young people. As of 2025, AI and computer science are still not part of the national K–12 curriculum, leaving Pakistan well behind India and many African nations that have already embedded tech into school systems.

But here’s the catch: these initiatives run parallel to the state, not with it. AI and computer science still aren’t part of Pakistan’s national school curriculum, unlike in India, or even some African countries, that have already started prepping their kids for a digital future.

The logistics sector is a rare case where AI is creeping in quietly. Companies like Bykea, InDrive, Careem, TCS and others are now using machine learning to predict deliveries, optimise routes, and improve support systems. These are smart, necessary moves, but again, they’re driven entirely by private innovation. There’s no AI-enabled traffic system, no citywide mobility upgrades like the ones China is rolling out.

E-Commerce is where Pakistan’s AI story feels the most real. One of the most tangible examples of AI use in Pakistan is in this sector, where Daraz, an online marketplace in Pakistan and South Asia, has implemented advanced AI and machine learning systems across its operations.

“Being customer-centric and data-first means that our investments in advanced technologies are always aimed at enhancing our services,” Daraz notes in its latest AI integration update.

Daraz utilises AI in product recommendations, fraud detection, personalised search results, and inventory management, optimising the platform for over 23 million products across 100+ categories. In a competitive and culturally diverse market, the company has built personalisation engines that factor in age, gender, income, industry, and regional preferences, significantly increasing user engagement and conversion rates.

The company’s Seller Center, a platform for over 240,000 marketplace sellers, uses AI-powered chat support, real-time agent monitoring, and a multi-language translation model that has translated over 6 million products into local languages. This not only makes the platform more accessible to non-English-speaking users but also improves seller-customer alignment across regions. It’s one of the few examples where AI is directly impacting economic empowerment and SME growth in Pakistan.

Finance, agriculture, and manufacturing have barely scratched the surface. AI chatbots could easily improve customer service in banks. Precision farming tools could double yields in agriculture. But without serious backing, these remain possibilities, not plans.

No national plan, no serious investment

Here’s the problem: there’s no national AI strategy to bring it all together.

Despite some progress in private sectors like e-commerce and logistics, Pakistan lacks a comprehensive national AI strategy. Unlike India’s $1.25 billion IndiaAI Mission or China’s $47.5 billion semiconductor fund, Pakistan has not allocated any significant public budget for AI-specific infrastructure, research, or talent development.

While the Ministry of IT & Telecom has floated draft versions of an AI policy in the past, none have been officially implemented or budgeted. In contrast, India has rolled out dedicated AI research parks, national language AI tools, and centers of excellence, while China has deployed AI in public health systems, military R&D, and industrial automation.

Pakistan also lacks foundational digital infrastructure, no national AI supercomputing cluster, limited cloud accessibility and compute power outside of private providers, and no public data governance law or national AI ethics framework.

This absence of policy clarity and public investment means that even when Pakistani talent is trained in AI, they often leave the country for better-funded ecosystems, further draining local capacity.

While isolated pockets of innovation exist, Pakistan's current approach to AI is largely reactive and fragmented. Without a coordinated national strategy, Pakistan risks becoming a follower in a race where its peers are already defining the rules.

The education gap

If there’s one place where Pakistan’s slow pace in artificial intelligence becomes not just obvious but downright alarming, it’s in education.

Yes, there are universities offering AI degrees. Yes, there are coding bootcamps and self-taught developers doing remarkable work. But if you zoom out, the bigger picture is stark: Pakistan is raising a generation of students for a world that may no longer exist by the time they graduate.

While other countries are building AI-literate societies from the ground up, Pakistan is still debating whether computer science should even be a core subject in schools. According to the AI Index Report 2025, nearly two-thirds of countries globally now offer AI or computer science education from the school level. In India, children are introduced to coding from Grade 6 as part of the National Education Policy 2020. In China, AI is embedded into the very architecture of their middle and high school curriculums, supported by AI labs, specialized teacher training, and state-sponsored learning platforms. Even countries like Rwanda and Kenya, with far fewer resources, have realized that digital literacy isn’t optional anymore, it’s survival.

In Pakistan, meanwhile, most public schools still treat computer science like an extra subject, if they offer it at all. There’s no AI content in the national curriculum. There’s no AI literacy goal, no standardization for teacher training, and no cohesive plan for integrating AI skills into mainstream education. In many government classrooms, there isn’t even reliable electricity, let alone internet-enabled smartboards or AI labs.

This isn’t just a missed opportunity, it’s a structural failure. We are not preparing children for the future that is already here.

At the higher education level, some institutions are trying to catch up. NUST now offers a full-fledged Bachelor of Science in Artificial Intelligence, along with graduate courses in machine learning, deep learning, and natural language processing (NLP). Its School of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science (SEECS) is one of the few academic departments tying research to real-world applications, from traffic management systems to smart agriculture projects.

FAST-NUCES, one of the country’s premier computer science universities, has embedded AI and data science into its undergraduate and graduate programs. Students work on practical, high-impact final-year projects, ranging from fake news detection algorithms to AI-based early diagnostics for diseases like cancer. Similarly, GIKI, COMSATS, and ITU Lahore have introduced AI-focused coursework and selective research labs focusing on fields like robotics, computer vision, and autonomous systems.

These are important advances, but as Professor Dr. Yasar Ayaz, Chairman of the National Center of Artificial Intelligence (NCAI), notes, "the progress remains urban, elitist, and fragmented." Smaller universities, especially those outside major cities, lack the trained faculty, funding, and policy support to build or sustain AI programs. “Even where research is happening,” says Dr. Ayaz, “there’s almost zero connection between universities, government departments, or private industry. Whatever research gets done mostly stays within classrooms, it doesn’t transition into policy or products.”

Without a national AI research council to align priorities or fund projects systematically, AI education in Pakistan risks becoming a luxury available only to the urban elite, leaving rural populations and marginalized communities even further behind.

Without a national AI research council to align priorities or fund projects systematically, AI education in Pakistan risks becoming a luxury available only to the urban elite, leaving rural populations and marginalized communities even further behind.

Faced with institutional inertia, Pakistan’s youth has started creating its own parallel paths into the AI world. Organizations like the Saylani Welfare Trust run the Mass IT Training Program, training thousands of young Pakistanis in AI, blockchain, and Web3 technologies, free of cost. The Presidential Initiative for Artificial Intelligence and Cloud Computing (PIAIC), spearheaded by Panacloud, offers flexible, remote certifications in AI, data science, and cloud technologies, reaching beyond big cities into second- and third-tier towns.

Women-focused initiatives like CodeGirls and Standard Chartered Women In Tech Pakistan are opening doors for female students who have historically been excluded from tech education. In urban centers like Karachi and Lahore, these programs offer coding bootcamps, AI training, and mentorship opportunities, first steps toward building a more inclusive AI workforce.

These efforts are transformative. They are changing lives. But they are running on volunteer energy, donor funding, and the sheer resilience of Pakistan’s young people. They are not yet part of the formal education system, which means their reach, consistency, and sustainability are limited.

As Dr. Ayaz explains, “To fully realize Pakistan’s potential as a digitally empowered economy, there is an urgent need to scale these programs beyond major cities into remote, underserved, and marginalized communities. Only then can we democratize access to AI education across the country.”

Encouragingly, Pakistan’s NCAI has created a 10-year AI roadmap, closely aligned with the government’s broader URAAN Pakistan vision for digital transformation. This roadmap targets twelve key sectors, ranging from governance and healthcare to agriculture, fintech, and education, where AI can create immediate and lasting impact.

Through initiatives like the AI Nexus Bootcamp, AI for Leaders program, and international collaborations like the AI Development Professional (AIDP) course with the University of Bologna, NCAI is attempting to build a comprehensive, multi-tiered AI talent pipeline. Training is happening at multiple levels, from senior leadership to grassroots developers aged 16–24.

But the success of these programs depends on government commitment. Right now, national AI policy frameworks exist only in draft form. There is no mandate for AI education in public schools. No national budget allocated to equip classrooms with AI-ready infrastructure. No significant investment in localizing AI content into Urdu and regional languages, which would be essential for scaling access beyond urban centers.

More worrying still, there is no serious conversation around Responsible AI, how we teach ethics, fairness, data privacy, and the societal risks of unchecked algorithms. In a world grappling with deepfakes, surveillance technologies, and algorithmic discrimination, Pakistan’s silence on AI ethics could have devastating consequences.

If Pakistan continues along its current path, relying on NGOs, a few elite universities, and volunteer energy, it will miss the real prize: a national AI-ready workforce that can compete globally. Instead, it will keep exporting its brightest minds to foreign tech hubs, while local industries stagnate under outdated skills and technologies.

Dr. Ayaz captures the opportunity and the urgency perfectly. “Through visionary programs and human capital investment, Pakistan has a real chance to leapfrog into the future. But we must act fast to make AI a cornerstone of national growth, not a privilege for a few.”

The clock is ticking. The future won’t wait.

Regional comparison

While Pakistan struggles to define a clear AI roadmap, its regional neighbours are moving decisively, embedding artificial intelligence into national development agendas, public services, and education systems.

China is leading not just the region but also the world. Backed by its 2017 New Generation AI Development Plan, China now accounts for nearly 70 per cent of global AI patents and 23.2 per cent of AI research publications, according to the AI Index Report 2025. AI is embedded into smart cities, manufacturing, healthcare, and national surveillance systems. China has even developed its own large language models, rivaling Western giants, and is investing heavily in AI chips and supercomputing to stay ahead.

India has emerged as the region’s most dynamic AI adopter, launching the $1.25 billion IndiaAI Mission to democratise access to AI tools, infrastructure, and talent development. Its National Education Policy 2020 introduces coding and AI from Grade 6, while public initiatives are leveraging AI in agriculture, healthcare, and regional language translation. AI startups in India raised over $5 billion in 2024, backed by strong government-industry collaboration.

Bangladesh, too, has made notable progress under its Vision 2041. With AI learning modules introduced in public schools and machine learning used for health surveillance and agriculture, the country is aligning digital skill-building with its national development strategy.

Sri Lanka, despite facing economic challenges, has initiated pilot projects using AI in disaster management, climate resilience, and telemedicine, often supported through international partnerships.

While China and India dominate AI innovation and skill-building, Pakistan is starting to carve its own regional alliances. According to Dr. Ayaz, China has recognized Pakistan’s emerging AI capabilities, leading to landmark collaborations.

“The MoUs signed between NCAI and top Chinese institutions open new avenues for Pakistan to export AI technologies through the CPEC corridor, harnessing the broader Belt and Road Initiative to reach global markets,” he explains.

These collaborations offer Pakistan a rare opportunity to leapfrog traditional barriers, if supported by parallel investments in local talent and infrastructure.

In contrast, Pakistan remains without a national AI strategy, has no formal AI integration at the school level, and has made minimal public investment in AI research or infrastructure. While some private innovation exists, there is no policy cohesion to match the regional momentum.

This growing divide suggests that Pakistan is not just behind; it’s at risk of being left out of the region’s AI future altogether.

The cost of inaction

The consequences of Pakistan’s slow embrace of artificial intelligence are not theoretical, they are already unfolding in ways that will deepen economic inequality, widen the skills gap, and erode global competitiveness if left unaddressed.

Artificial intelligence is rapidly becoming the engine of economic productivity. According to the AI Index Report 2025, companies that integrate AI tools into their operations report productivity gains of up to 40 per cent in sectors like finance, healthcare, and manufacturing. As AI automates routine tasks and enhances decision-making, countries with strong AI ecosystems are set to capture the next wave of global economic growth. Pakistan’s failure to adopt AI at scale risks pushing its industries, already struggling with efficiency, further behind in global supply chains.

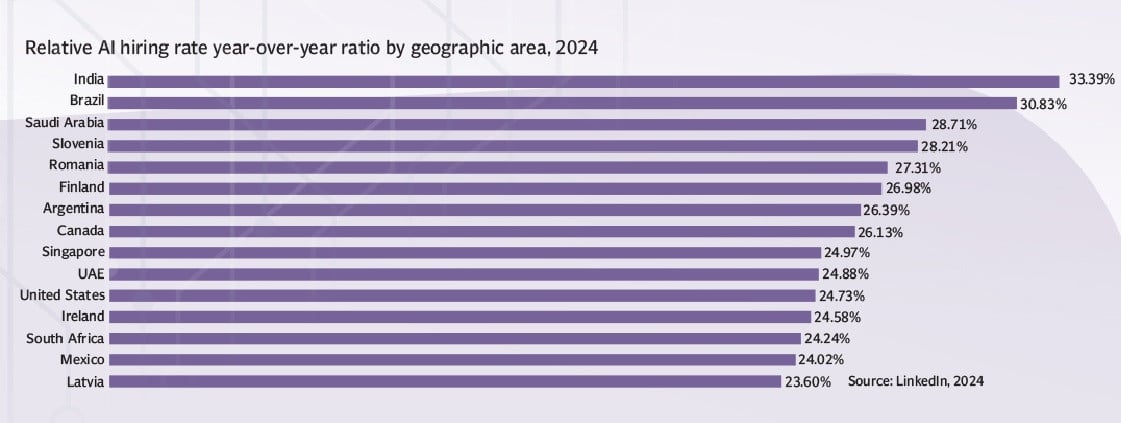

Moreover, the job market is undergoing a silent transformation. Globally, 60 per cent of workers now expect that AI will fundamentally change their jobs within the next three years. Yet, in Pakistan, most workers, especially those in traditional sectors like textiles, agriculture, and retail, remain unaware or unprepared for this shift. Without investment in AI skills and retraining, Pakistan’s youth, who should be its greatest asset, could instead face structural unemployment in an increasingly AI-driven economy.

The risks extend beyond economics. Countries are using AI for smarter governance: optimising traffic, predicting disease outbreaks, monitoring climate risks, and delivering targeted social services. In a region vulnerable to climate change and food insecurity, Pakistan’s failure to leverage AI for public sector innovation could prove devastating, leaving millions more exposed to preventable crises.

Finally, at a time when deepfakes, misinformation, and AI-enabled fraud are becoming serious threats, Pakistan’s lack of a regulatory framework leaves its digital and democratic spaces vulnerable. Without proactive AI governance, the country risks not just economic irrelevance but also social instability.

In short, the cost of inaction is not just falling behind, it is falling out of the race altogether.

What Pakistan should do now?

Pakistan still has time to catch up, but that window is closing fast.

The first step is simple, yet powerful: acknowledge AI as a national priority. Pakistan needs a clear, actionable AI policy, led by the Ministry of IT & Telecom, that not only outlines goals but also assigns budgets, timelines, and accountability. This policy should create a national framework for ethical AI, open datasets, infrastructure development, and cross-sector adoption.

Second, we must bring AI into our schools, not just elite private institutions, but government classrooms in every tehsil. A basic AI and digital literacy curriculum for Grades 6–12, combined with teacher training and offline toolkits for areas without Internet could begin to close the skills gap that’s already hurting our economy.

Third, Pakistan should launch a national AI innovation fund to support startups, researchers, and university projects. Public-private partnerships could enable young entrepreneurs to build local solutions in Urdu and regional languages, whether it’s chatbots for small businesses, smart irrigation for farmers, or accessible health tools for women.

And perhaps most importantly, we must tell our youth that they belong in this future, that AI is not something invented elsewhere for others to control. With focused effort, Pakistan could train a million young people in AI and related fields within the next five years. The talent is here. The hunger is here. What’s missing is direction.

Fortunately, the foundation for a national strategy is beginning to form. Under NCAI’s stewardship, Pakistan has developed a comprehensive 10-year AI roadmap, aligned with its broader digital vision under URAAN Pakistan.

“Through the stewardship of NCAI, Pakistan now has a strategic plan targeting twelve sectors, from healthcare and agriculture to fintech and defense, all modeled on global best practices,” notes Dr. Ayaz.

However, he warns that formulating plans isn’t enough. “The next critical step is to accelerate legislative adoption, moving from frameworks to enforceable AI ethics, data governance, and cybersecurity laws. This will build public trust, attract investment, and secure Pakistan’s future as a responsible AI nation,” he added.

Without fast-tracking these moves, Pakistan risks letting its early momentum slip away. We can choose to let the future happen to us, or we can help shape it. The time to choose is now.