In little more than a decade, social media has gone from novelty to necessity — an inescapable presence in modern life. What began as a space for connection and communication has evolved into a powerful engine of influence — and, increasingly, a source of instability and division. Its impact transcends geographical borders, reaching far beyond individual interactions to reshape politics, security, and public discourse across the world.

And it’s not just limited to Gen Z or Gen Y. Social media has become an integral part of everyone’s daily life. Platforms like YouTube, Facebook, X, Instagram, and TikTok have revolutionised how we socialise, learn, connect, communicate, disseminate and access information, and perceive the world. It has fuelled social and political movements, redefined the academic landscape, and opened new vistas for personal and professional growth.

However, arguably the most significant achievement of social media has been the democratisation of information. It has granted individuals the power to become publishers, dismantling the control once monopolised by traditional media giants, where only brands dictated the narrative. No longer passive consumers, netizens now have the ability to create, publish, and engage directly with their audiences.

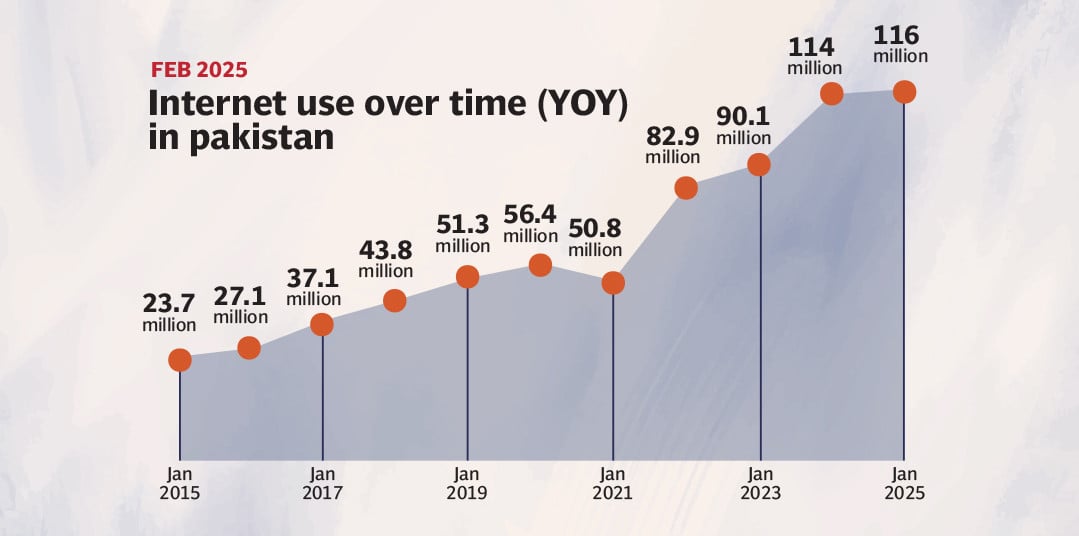

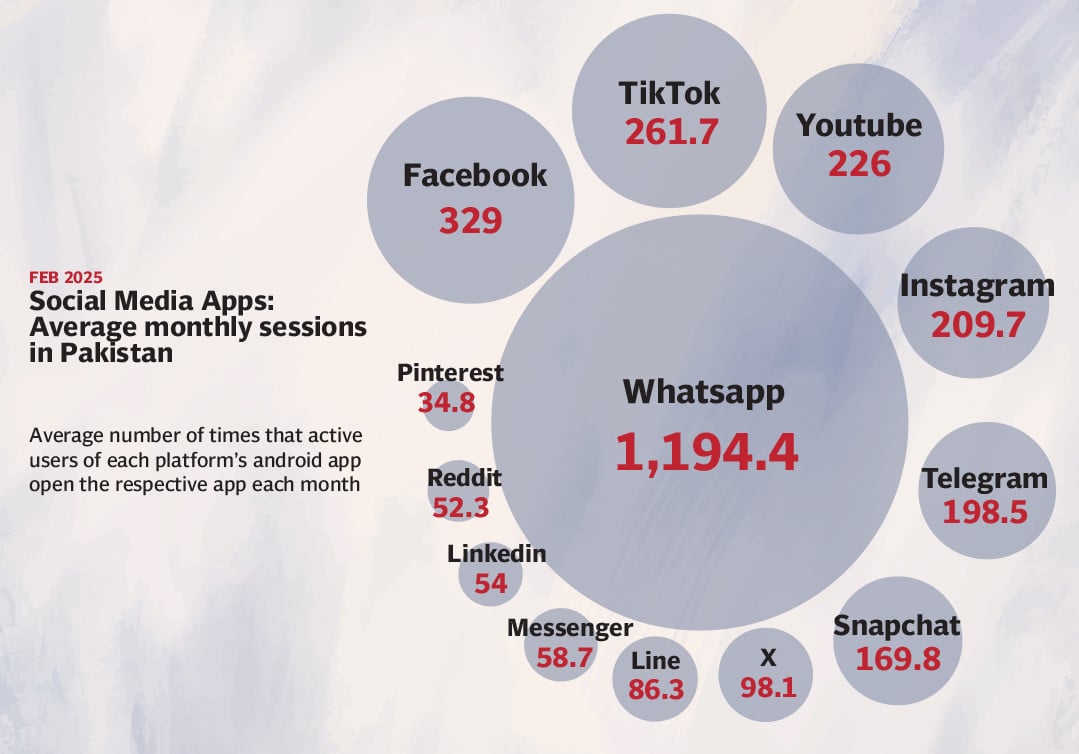

This transformation has been driven by the unprecedented spread of the Internet. According to the “Digital 2024” report by Meltwater and We Are Social, the number of active social media users has now surged past 5 billion worldwide — that’s 62.3% of the global population. The appeal of social media has only grown stronger, with various platforms experiencing explosive growth by tapping into ever-deeper user engagement. The latest figures show Facebook remains the most popular platform globally, with around 3.065 billion monthly active users, followed by YouTube (about 2.5 billion), WhatsApp (around 3 billion), Instagram (roughly 2 billion), and TikTok (close to 1.69 billion monthly users).

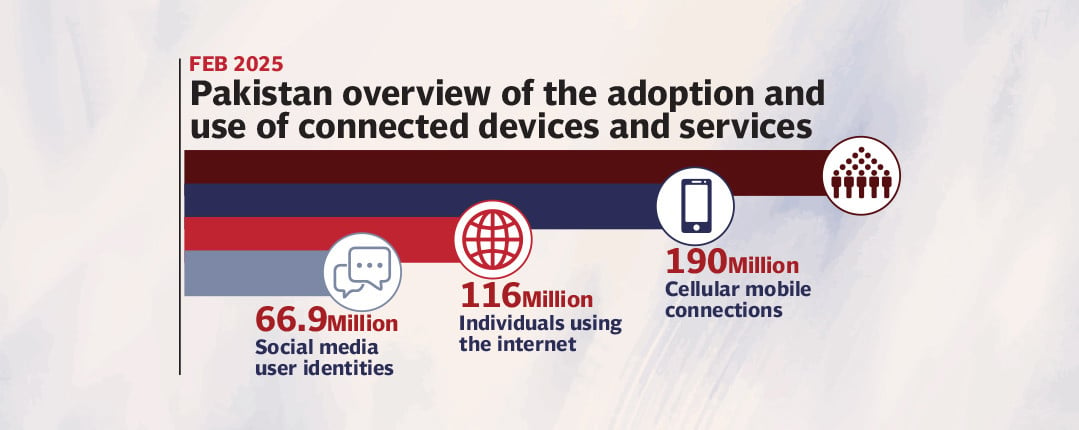

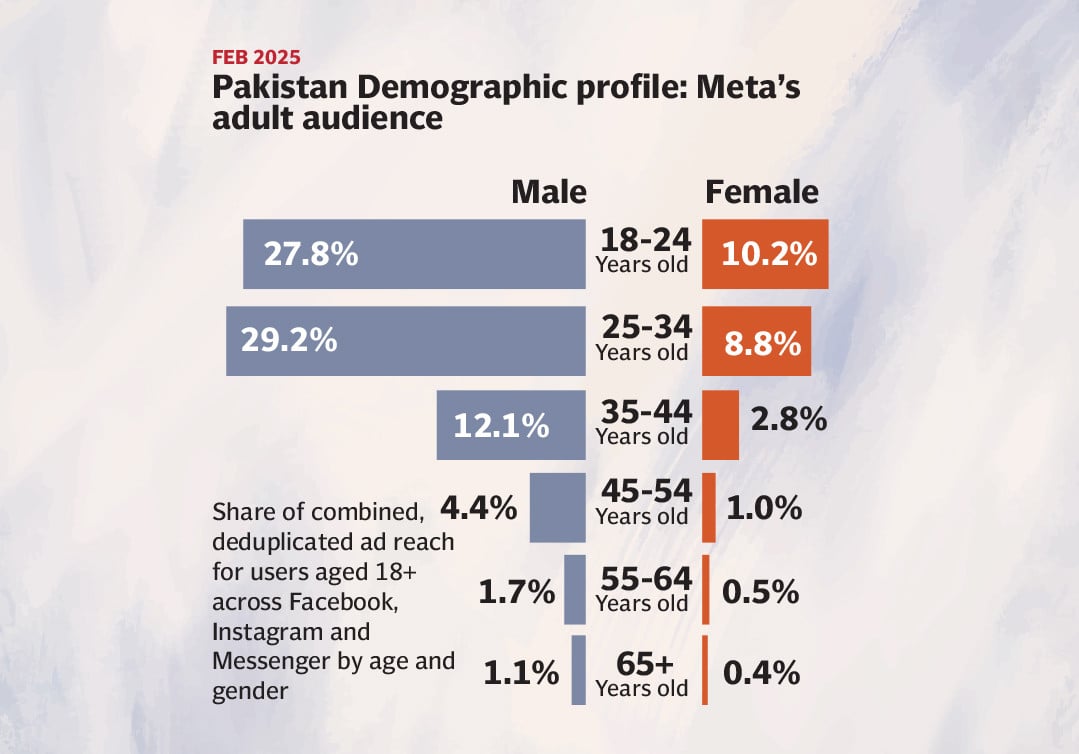

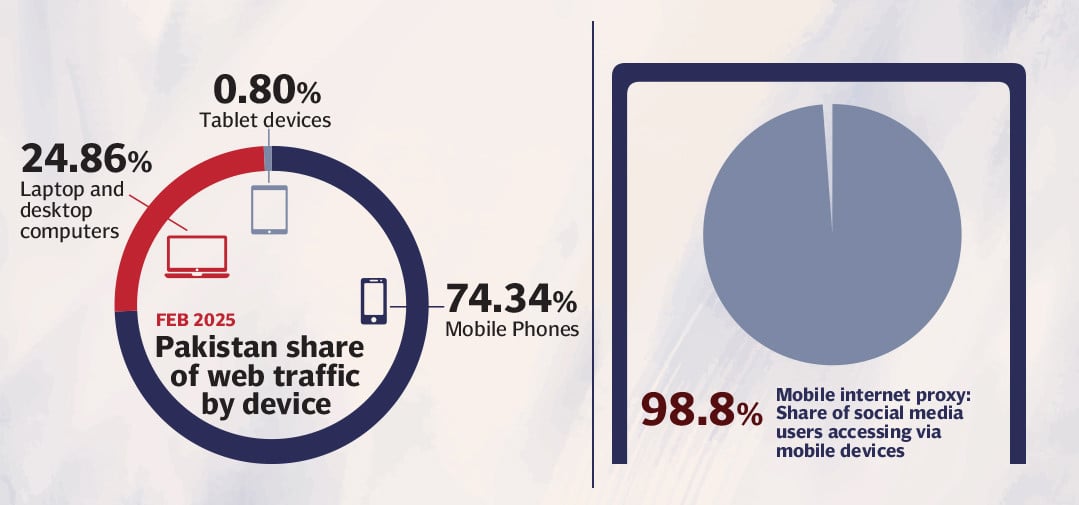

Mirroring global patterns, Pakistan’s social media landscape has also expanded dramatically, with digital engagement growing rapidly. According to the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority, as of January 2024, there were around 303.21 million active social media users in Pakistan. YouTube remains the most popular platform, with 71.7 million users, followed by Facebook (60.4 million), TikTok (54.4 million), and Instagram (17.3 million).

Digital downside

While digital media has transformed our lives in countless positive ways, it carries a darker undercurrent — a flaw not uncommon in the story of modern inventions. Over the years, social media has become a conduit to disseminate fake news, misinformation, and disinformation by anarchists, propagandists, conspiracy theorists – and even governments. Pizzagate, Pope’s purported endorsement of Donald Trump, conspiracy theories about COVID-19, and anti-Muslim rioting in UK are some of the examples of fake news and disinformation peddled on social media. Moreover, social media was used to fight a digital war in cyberspace during the Ukraine war and Gaza conflict.

“With a few keystrokes, the internet can connect like minded people over vast distances and even bridge language barriers. Whether the cause is dangerous (support for a terrorist group), mundane (support for a political party), or inane (belief that the earth is flat), social media guarantees that you can find others who share your views,” say PW Singer and Emerson T Brooking, the authors of “LikeWar: The Weaponization of Social Media.”

Weaponisation of social media

Terrorists and extremists, too, have understood the power of social media, using it to advance both their narratives and operations. The United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute has admitted that violent extremist and organised criminal groups have successfully exploited vulnerabilities in social media to manipulate people and disseminate conspiracy theories.

“Social media platforms… have become a major gateway for terrorists,” writes Abdulaziz Al-Zaben in a study titled “The use of the Internet and social media in recruiting and organising terrorist groups” published in “Drivers of Terrorism”, a monthly publication issued by the Islamic Military Counter-Terrorism Coalition.

The study shows that various social media platforms, especially YouTube, X, Facebook, WhatsApp, and Instagram have become the primary recruiters for extremists and a crucial tool in the hands of terrorist groups for spreading their ideas, beliefs, planning, executing their goals, and recruiting members. “Excessive use of the internet has granted terrorists numerous advantages, such as concealment, the ability to coordinate continuously, and finding financial sources outside the supervision of governments and central banks,” it adds.

The migration of terrorist and extremist groups to social media has been motivated by several factors, including its promise of anonymity, global reach, encryption, real-time communication, recruitment, propaganda, and swift and low-cost content creation among other things. These groups have increasingly utilised various social media platforms for recruitment and radicalisation, communication and coordination, the promotion of violence, and resource mobilisation.

Beyond these tactical uses, digital warfare also plays a pivotal role in terrorists' psychological operations (psyops), leveraging information to push their narratives, manipulate emotions, and distort objective reasoning to confuse, divide, and demoralise the adversary. Social media amplifies that.

Popular platforms have become a cheap psyops tool not just in politics, culture wars, and economic manipulation but also for terrorists and extremists who harness them to get traction for their activities. “Terrorism is theater,” RAND Corporation analyst Brian Jenkins wrote in a 1974 report that became one of terrorism’s foundational studies. “Command enough attention and it didn’t matter how weak or strong you were,” he wrote.

The self-declared Islamic State, or ISIS, was the first extremist group that effectively did that during its invasion of Iraq 2014. “There was a choreographed social media campaign to promote it, organised by die-hard fans and amplified by an army of Twitter bots. They posted selfies of black-clad militants and Instagram images of convoys that looked like Mad Max come to life,” say Singer and Emerson. “To maximise the chances that the Internet’s own algorithms would propel it to virality, the effort was organised under one telling hashtag: #AllEyesOnISIS,”

“The Islamic State didn’t simply use the Internet as a tool; it also lived there. In the words of Jared Cohen, director of Google’s internal think tank, ISIS was the “first terrorist group to hold both physical and digital territory,” Singer and Brooking write. In the Syrian civil war where ISIS first roared to prominence, nearly every extremist group used YouTube to recruit, fundraise, and train.

The rising weaponisation of social media by terrorists and extremists is unsettling enough, but what is more chilling is the looming prospect of emerging technologies — AI and encrypted messaging apps, for instance — being wielded by such outfits to amplify their ideologies. “It is still a little early to understand the impact of AI on extremist groups, but there is no reason to think that these new technologies won’t be used by them as well. Some possibilities might include their ability to generate fake videos, audio, or images to spread disinformation, fabricate enemy atrocities, or glorify their own violence. They could use AI language tools to mass-produce extremist literature, fake news, or recruitment materials. We haven’t seen this at any large scale yet, but it is certainly a possibility,” says Amarnath Amarasingam, Assistant Professor in the School of Religion at Queen’s University in Ontario, Canada.

Buckling under growing pressure over the proliferation of extremist and hateful content on their platforms, mainstream social media companies made some efforts to moderate content, but these measures were reactive rather than proactive. “I think platforms need to maintain their commitment to trust and safety and ensure that pressure continues to be placed on these hate movements online. We’ve had a lot of success in keeping them largely outside mainstream spaces for many years. It would be a shame if all this progress were reversed,” adds Amarasingam.

However, recently, mainstream social media platforms have begun to scale back their moderation policies, inadvertently giving terrorist groups more room to operate in cyberspace. “The relaxation of content moderation policies on social media platforms has, in fact, provided extremist groups with greater opportunities to disseminate their ideologies and recruit members,” cautions the academic, whose research focuses on terrorism, radicalisation, conspiracy theories, and online communities.

TTP’s tech embrace

In Pakistan, the TTP terrorist umbrella, officially designated as Fitna Al Khawarij, restructured its media wing, Umar Media, after the fall of Kabul to its ideological twin in August 2021, to make its information warfare more sophisticated, dynamic, and effective. Umar Media was remodeled on the Afghan Taliban’s Al Emarah Media to increase its effectiveness as a propaganda tool. This move, according to some experts, played a crucial role in the ongoing resurge in their attacks in Pakistan.

“Extremist organisations in Pakistan, notably the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan, have effectively utilised online platforms to disseminate propaganda and recruit members. Umar Media, the TTP’s media arm, produces content in multiple languages, including Urdu, Pashto, and English, to reach a broad audience,” says Amarasingam.

Umar Media produces audios, videos, and podcast series, along with digital magazines. The content is published on the group’s website and disseminated through its social media accounts and encrypted messaging platforms such as WhatsApp and Telegram. The group also sends daily updates with slick infographics to media persons in the name of its spokesperson Mohammed Khorasani. Several TTP social media accounts have been reported to platforms and blocked, but the group employs evasion tactics by exploiting vulnerabilities in different platforms.

BLA enters cyberspace

In recent years, the TTP has developed a symbiotic relationship with other terrorists, extremists and anarchists in Pakistan, especially the banned Baloch separatist groups. And this symbiosis is becoming increasingly visible in their tactics, such as use of suicide bombings, high stakes and unconventional attacks – and above all their communication strategies.

“Baloch separatist groups, particularly the Baloch Liberation Army (BLA), have relied on modern information and communication technologies, especially social media platforms, to project their militant prowess, justify their use of violence, attract recruits, and challenge state narratives,” writes Sajid Aziz in his article “Digital Warfare: The Baloch Liberation Army’s Tactical Use of Social Media in the Herof Attack” for Global Network for Extremism and Technology, an academic research initiative backed by the Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism (GIFCT).

The Baloch groups, which have been fighting a simmering insurgency in Balochistan for over two decades now, have exploited endemic political grievances in the impoverished province to to sell their narrative and enlist recruits, especially among the educated youth. And they have been immensely aided by social media in their campaign. These groups have become more sophisticated in their use of modern digital technologies as was evident from the recent hijacking of Jaffar Express passenger train by Majeed Brigade, the special operation unit of BLA. The group churned out AI-generated videos to amplify their unprecedented attack and grab global media spotlight.

Turning TikTok against CPEC

The BLA, the deadliest of all Baloch groups, has increasingly set its sights on Chinese nationals as part of its efforts to disrupt the multibillion-dollar China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) project. Pakistani officials allege that Baloch Yakjehti Committee (BYC), which positions itself as a rights group, serves as a political front for the BLA, lending legitimacy to its narrative.

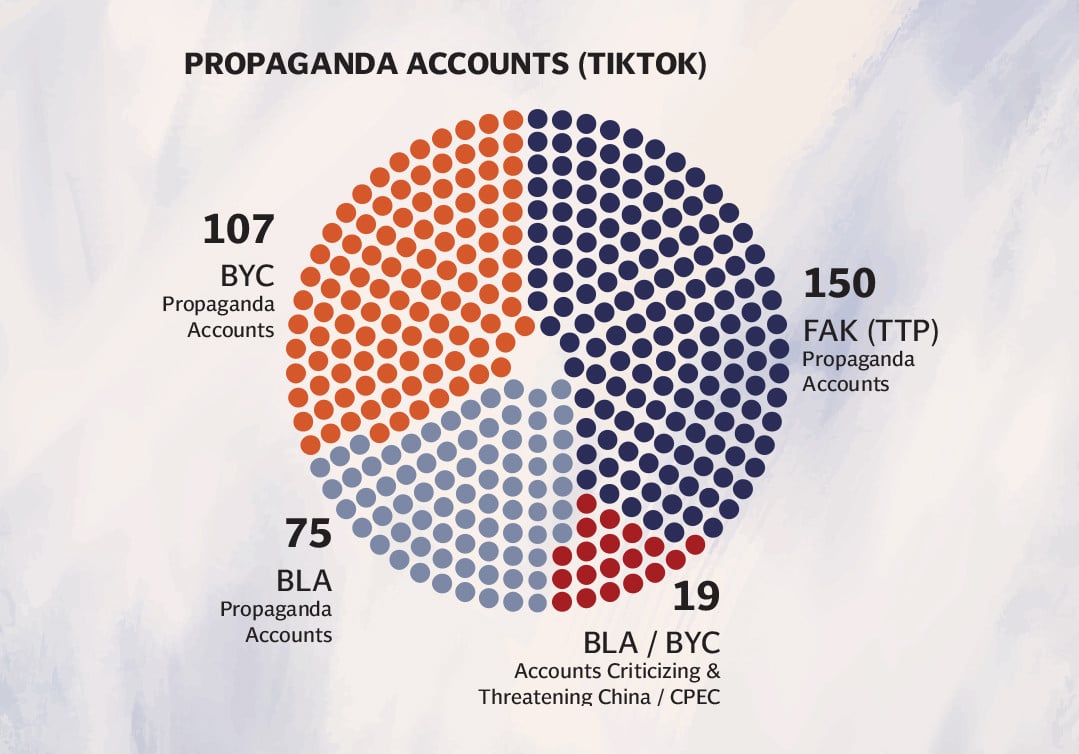

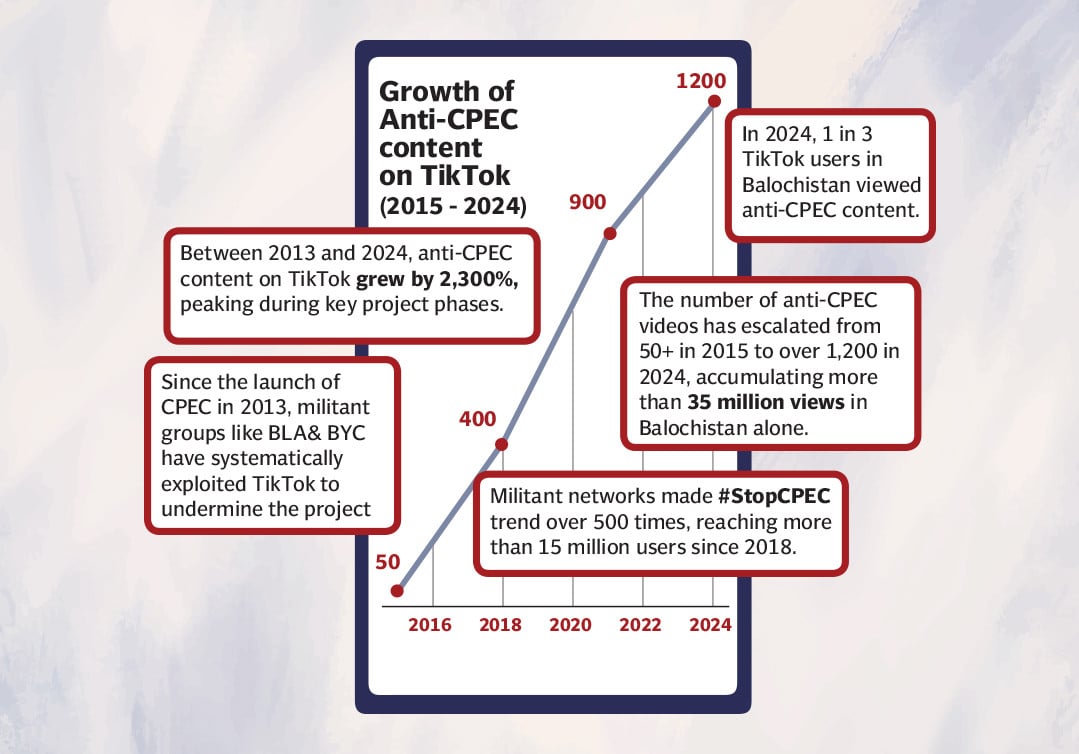

In a striking contradiction, the BLA and BYC, despite their fierce opposition to China’s presence in Balochistan, have used TikTok — owned by the Chinese company ByteDance — to fuel their anti-CPEC campaign. The number of anti-CPEC videos on TikTok has seen a massive surge – from over 50 in 2015 to more than 1,200 in 2024, garnering more than 35 million views in Balochistan alone. The Baloch groups – BLA and BYC in particular – weaponise TikTok’s algorithm to disseminate fake news and disinformation against CPEC to portray it as an attempt to usurp Balochistan’s resources.

The rise in TikTok activity from Balochistan is nothing short of alarming. It shows that anti-CPEC content on the platform increased by a staggering 2,300% since its inception, peaking during key project phases. One in 3 TikTok users in Balochistan have viewed anti-CPEC content in 2024. Similarly, Baloch groups used #StopCPEC hashtags to trend over 500 times, reaching more than 15 million users since 2018. TikTok’s lax content moderation policies enabled these groups to exploit the platform in their attempt to change public perception of the project.

This coordinated campaign of digital disinformation, conducted via a Chinese social media platform to undermine China’s $65 billion investment, serves as a textbook example of hybrid warfare. CPEC is a lifeline for Pakistan’s economy and the flagship project of China’s massive Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and any threat to this colossal project should be a joint responsibility.

Mounting a cyberdefence

In light of these emerging digital threats, a collaborative approach across various sectors is essential to counter the weaponisation of TikTok by Baloch groups. Diplomatically, Pakistan must engage with China to address concerns over the exploitation of TikTok’s algorithm in the campaign against CPEC. The two nations could establish a joint “tech task force” to oversee digital security related to CPEC and develop coordinated responses. Operationally, intelligence-sharing mechanisms should be strengthened to track and analyse the origins and spread of anti-CPEC content. Additionally, enhancing cyber surveillance capabilities will be crucial to monitor and respond to radical online activities in real time.

The two countries should also collaborate on academic research to study hybrid warfare, digital propaganda, and their implications for national security. They can engage pro-CPEC influencers to blunt extremist narratives besides establishing partnerships with fact-checking organisations to debunk fake news and disinformation campaigns against CPEC.

On the monitoring front, efforts should be made to identify and expose foreign digital interference aimed at magnifying anti-CPEC sentiments. Relentless attribution of hostile actors — whether state or non-state — should be made part of the national cyber defence strategy. On the part of TikTok, a local content moderation team should be set up in Pakistan to flag and take down harmful content swiftly. Accounts affiliated with banned groups such as BLA and BYC should be identified and blocked in coordination with Pakistani authorities. AI-driven tools could also be implemented to detect and neutralise emerging digital threats against CPEC.

China, for its part, must take steps to address the algorithmic vulnerabilities of TikTok, ensuring that it doesn’t amplify radical or anti-CPEC narratives. Its regulators should implement stricter guidelines on political content that targets national infrastructure or bilateral projects like CPEC.

On Pakistan’s part, the existing cyber laws need to be strengthened, no doubt without compromising on free speech, to criminalise digital warfare against state projects and penalise those promoting toxic propaganda. A counter-narrative strategy should be initiated, focused on creating high-quality, engaging, and factual content highlighting CPEC’s benefits. Regional digital campaigns targeting youth in Balochistan and other sensitive areas should also be prioritised to combat radicalisation. Public awareness programs must be introduced to educate young users about the dangers of online misinformation and digital extremism.