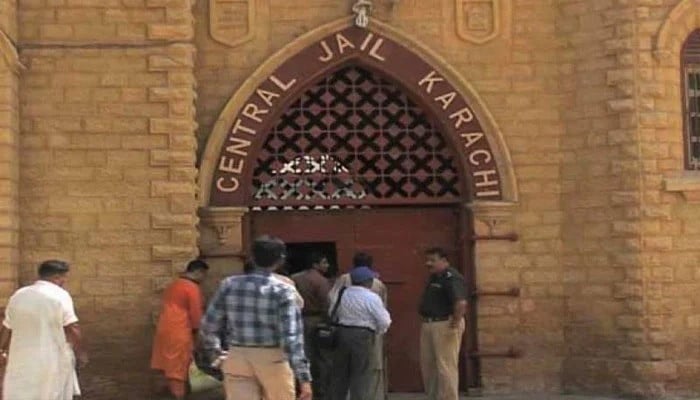

The Central Jail Karachi is a labyrinth of iron bars, stone walls, and silent screams. Its rigid concrete exterior holds decades of history, while the lives imprisoned within echo with dreams of freedom. Time may have stood still here, but dreams, desires, and emotions persist, albeit now expressed in a new language, a new style of rap, in the words of poetry, and the sound of pain.

As you enter the jail, there is a strange silence, covered by the rumble of heavy gates. Steel on steel ring fades in the air, but echoes of the steps of prison guards reverberate against antiseptic walls. Behind these four walls is not only punishment, but tales, the tales of lives that could have been different, but circumstances and fate steered them in here.

Here, a few hands draw images on iron walls with charcoal pieces, a few fingers weave complex patterns in notebooks, and a few tips vent their inner agony into lyrics and poetry. But the most potent voices are those of the rap singers, the inmates who take the courage to speak out about their wounds using words, turn their pain into rhythms, and pour their emotions into beats.

Eighty prisoners are confined to a single death row cell, while jihadists and mercenaries are housed separately from other convicted inmates and regular death row prisoners. “These prisoners were separated from the hardcore prisoners’ barracks due to ongoing Supreme Court hearings and verdicts,” says Muhammad Yousaf, DSP and media coordinator, Karachi Central Jail. “The Supreme Court has released many prisoners who had been incarcerated for over 15 to 20 years, while others remain on death row awaiting the outcome of their mercy appeals.”

DSP Yousaf also shared that the longest-serving prisoner on death row has been awaiting either mercy or release for more than 26 years. “Among the 80 prisoners, individuals come from various provinces and regions of Pakistan,” he explains. “In accordance with criminal appeal procedures and available facilities, the jail administration also facilitates the transfer of prisoners to facilities closer to their family homes whenever possible.”

During my visit to the central jail, I observed a well-maintained and organised facility featuring beautiful scenery, artwork, crafts, a library, and paintings. The cleanliness of the jail was remarkable. I also witnessed prisoners engaging in various educational and creative activities. Some were attending music classes, others were painting, and many were busy with crafting. What stood out the most was that the instructors guiding these activities were also prisoners, contributing to a unique and rehabilitative learning environment within the jail.

“These crafts, artworks, and scenic paintings are not just for decoration or a way to pass the time, but also serve as a source of income for the prisoners,” says DSP Yousaf. “Many inmates are primary breadwinners for their families, and the jail administration, along with the government, assists them by selling their artwork and handmade items at different exhibitions.”

Prisoners have the opportunity to work both during class and inside their barracks. Additionally, some inmates support their fellow prisoners and their families by drafting legal applications and other documents.

The jail administration and the government also support inmates in pursuing education. According to Muhammad Yousaf, any prisoner who wishes to continue their studies is aided, enabling them to complete their education from matriculation to graduation. This initiative helps prisoners gain knowledge and develop skills that can aid in their rehabilitation and reintegration into society.

Among these prisoners is 28-year-old Jahangir, who completed his graduation while in jail, having only completed his matriculation before his arrest. In addition to furthering his education, he also learned fine arts and now serves as an art instructor for other prisoners. He shared that one of his former students, who has since been released, now sells his artwork and paintings professionally. Jahangir supports his family and wife by selling his artwork.

A group of prisoners gathered in a corner of the barrack, singing and learning music. While others sang, a young inmate played the drums. These prisoners expressed their thoughts, regrets, and emotions through their songs. The lyrics, written by the inmates themselves, conveyed their guilt, experiences, and lessons they wished to share with the younger generation outside the prison walls. However, despite their talent and meaningful messages, they lack a platform to bring their voices to the public and make an impact beyond the confines of the jail.

A new language has emerged among prisoners-rap. Once a symbol of the streets, underground cultures, and rebellion worldwide, it has now found a new voice behind bars. Here, it is more than just music; it is a protest, a truth, a confession. With nothing left to lose, these prisoners speak fearlessly, making their words the most honest. What they say comes straight from the heart, and as you listen to their songs, it becomes clear that their pain is not just their own but a reflection of society’s failures.

"Maula yeh bata, meri zindagi hai kya?" [O Lord, tell me, what is my life?] These were the words of a young prisoner on death row that he hummed at my request. The other prisoners sitting beside him bowed their heads, nodding in rhythm, as if they, too, were searching for the answer to that one question. This was not only a rap tune; it was a quiet revolution in the prison, a call for justice, and a reflection of the brutal truth of society.

Sin, punishment, and remorse were the themes that this young man chose to recite upon in his life. He explained how poverty, deprivation, and bad guidance had taken him on the wrong path, how one wrong move had relegated him to the shadows of the prison. But his voice carried more than just regret; it held a message. He was warning all those young souls standing on the streets, lingering in the shadows, on the verge of making the same choice.

"Yeh kis dagar par chal padi hai zindagi, har taraf hai bebasi hi bebasi"[On what path has life set foot, everywhere there is helplessness alone] the rap began with these words, and then a young man poured his heart out, sharing his story of regret. Through his lyrics, he confessed his crime and urged others to stay away from bad company, warning them not to make the same mistakes that led him here.

" Na manzil ki hai khabar, na hai raho ka pata" [No destination is known, nor any path is clear]. All these prisoners wait, some for death, others perhaps holding onto a quiet hope for forgiveness. Maybe, deep in their hearts, these travellers of unknown paths and uncertain destinations still cling to a glimmer of hope.

Every line of the rap, every beat, every word echoed against heavy prison walls, not just as a warning for prisoners, but to the world beyond. This song carried more than just raw emotion, it held a truth that many choose to ignore.

Rap is not just music, it is a mirror reflecting society. These prisoners don’t just tell their own stories—they expose the harsh realities of the world around them. They reveal how a poor child, deprived of education and opportunities, is pushed toward crime. They expose how the law is ruthless toward the weak yet lenient toward the powerful. And they admit their own responsibility for their fate, hoping to save others from making the same mistakes.

This is a new awakening within the prison, where music and poetry give voice to truth that perhaps can never be spoken out in courtrooms. This is not just the story of a prison, it is our story. This rap is not merely the voice of a prison singer, but the voice of every young soul on the brink of being lost to darkness.

The question is, are we willing to listen? Will we dismiss these voices as mere "cries of criminals," or will we try to understand the pain hidden within them? These rap songs are not just entertainment, but they are messages, carrying truths that may never reach us in any other way. These voices should not be confined within prison walls. We must listen, understand, and perhaps even learn from them.

Because, in the end, their story is our story. These are not just prison bars, they are the walls of fate, capable of shattering bridges and summoning the fiercest storm. Here, there are no colours of dreams, no light of hope—only the heavy chains of sin.

Rumisa Malik is a journalist based in Karachi and can be reached at rumisamalik70@gmail.com

All facts and information are the sole responsibility of the writer