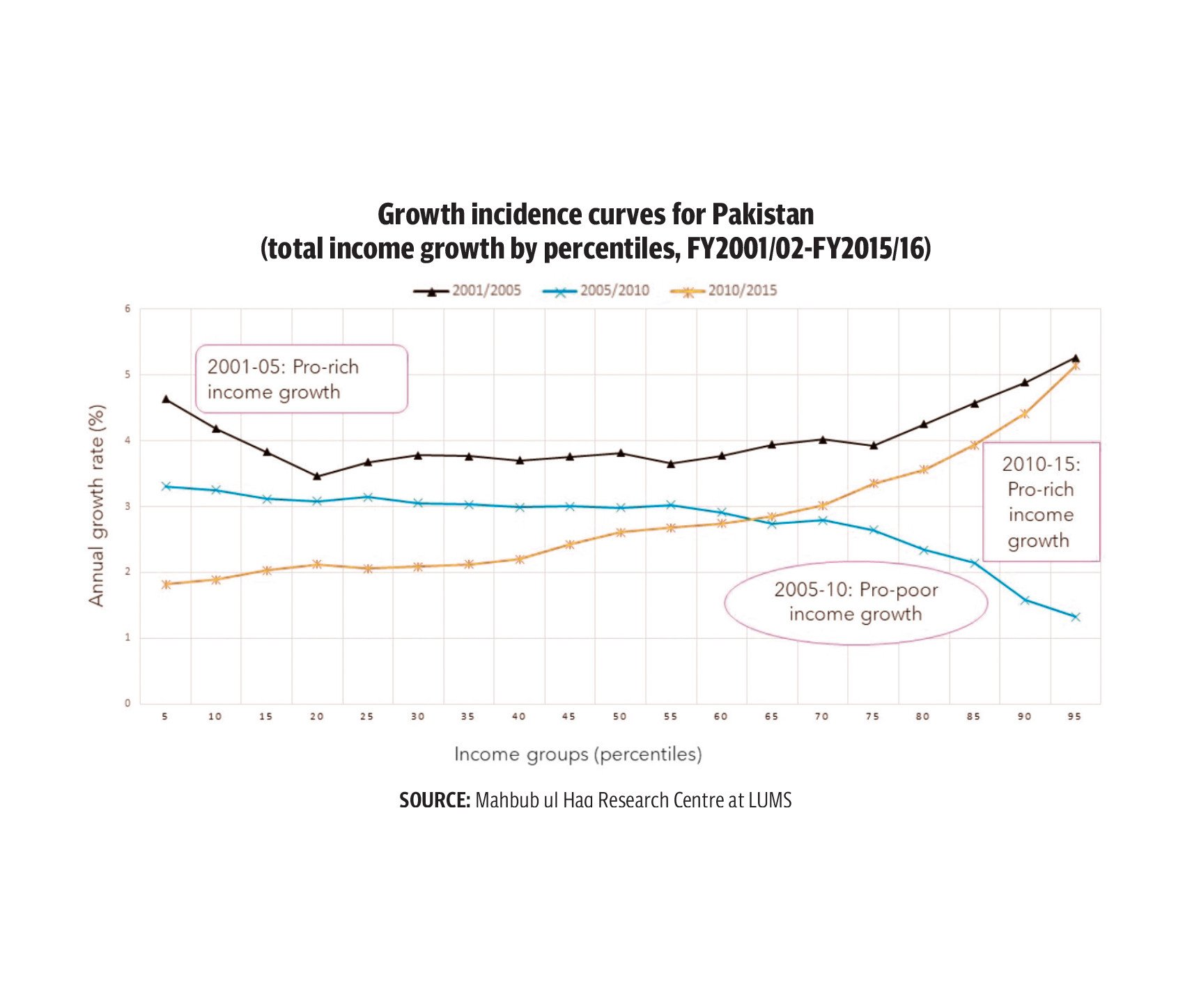

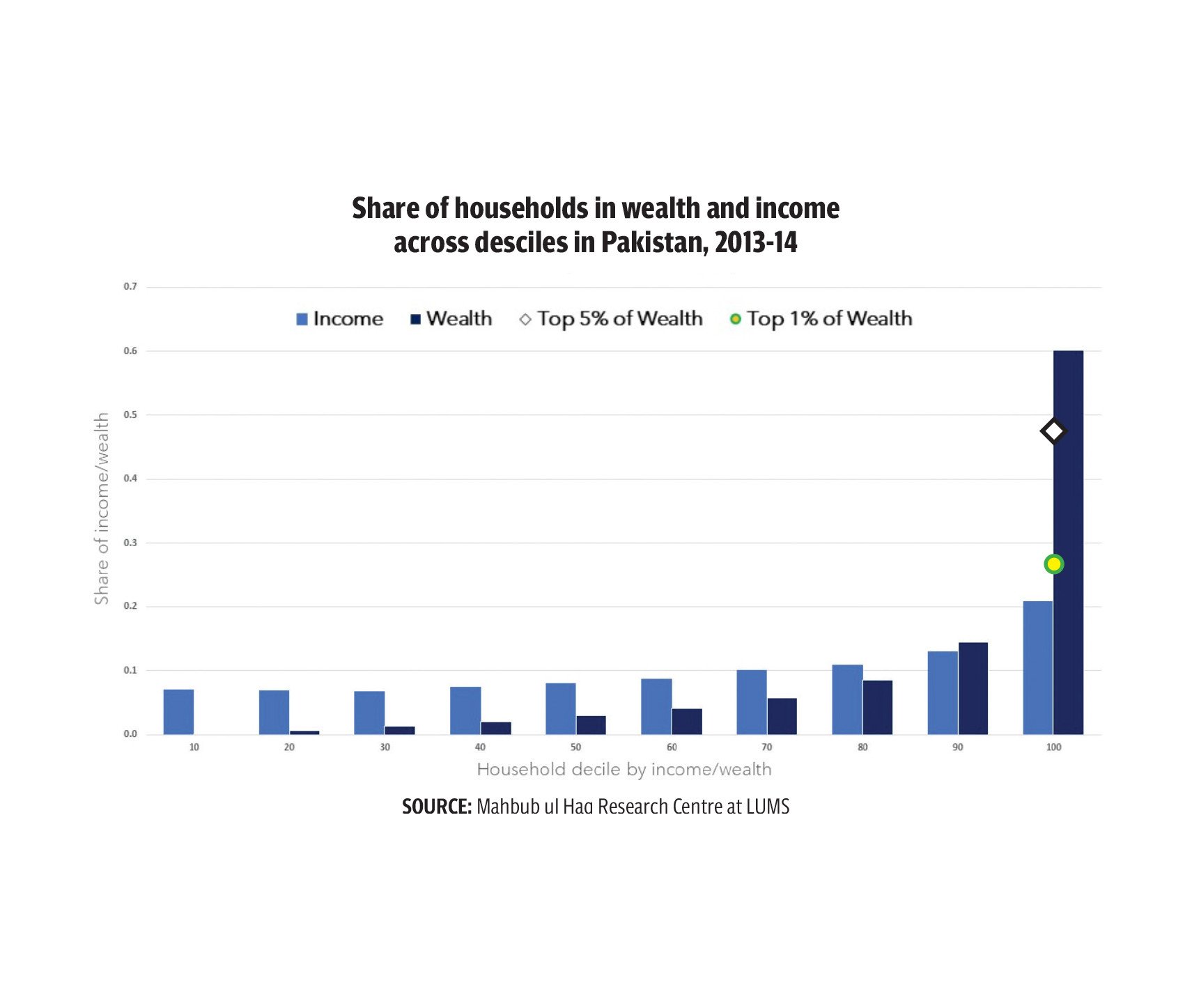

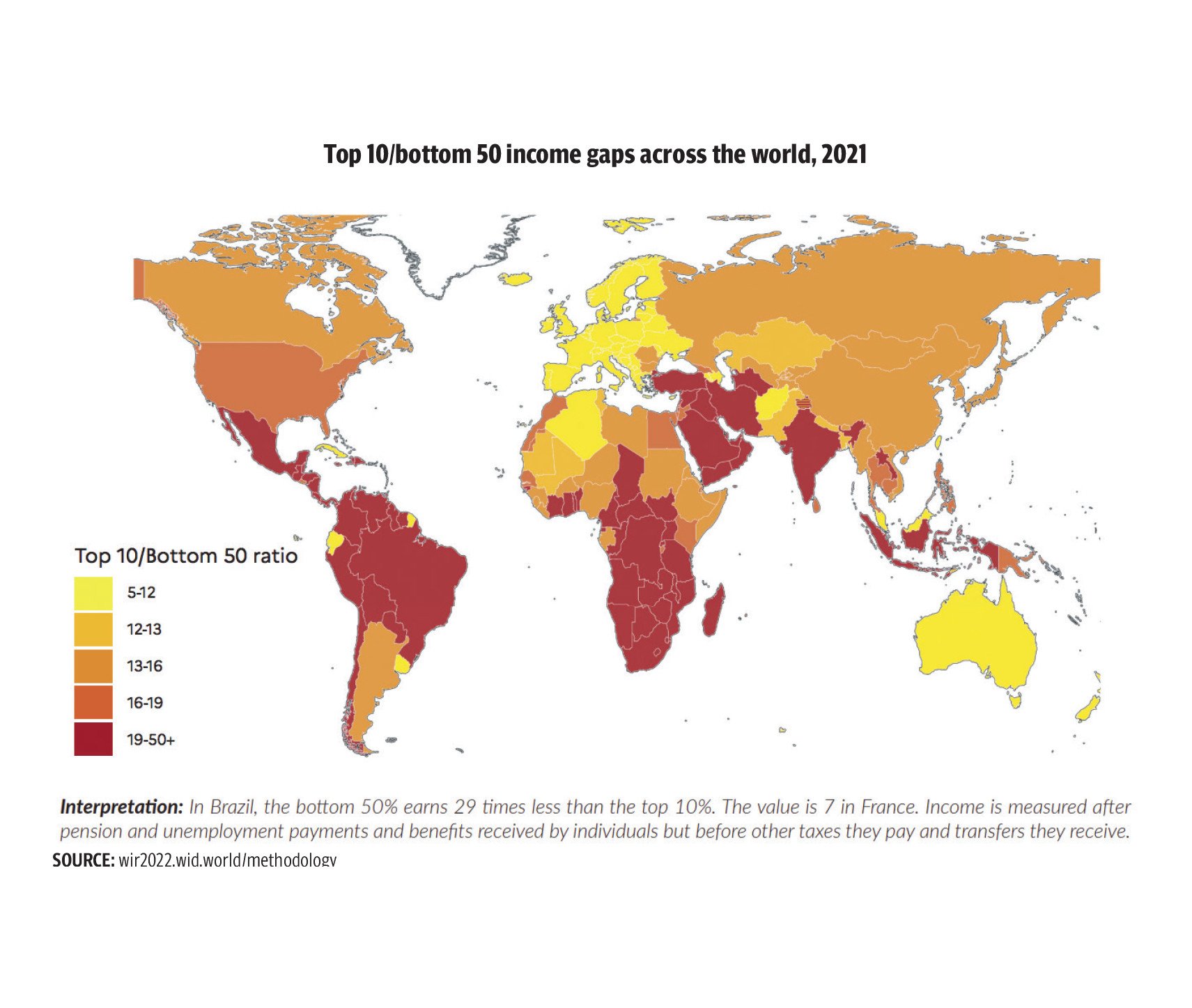

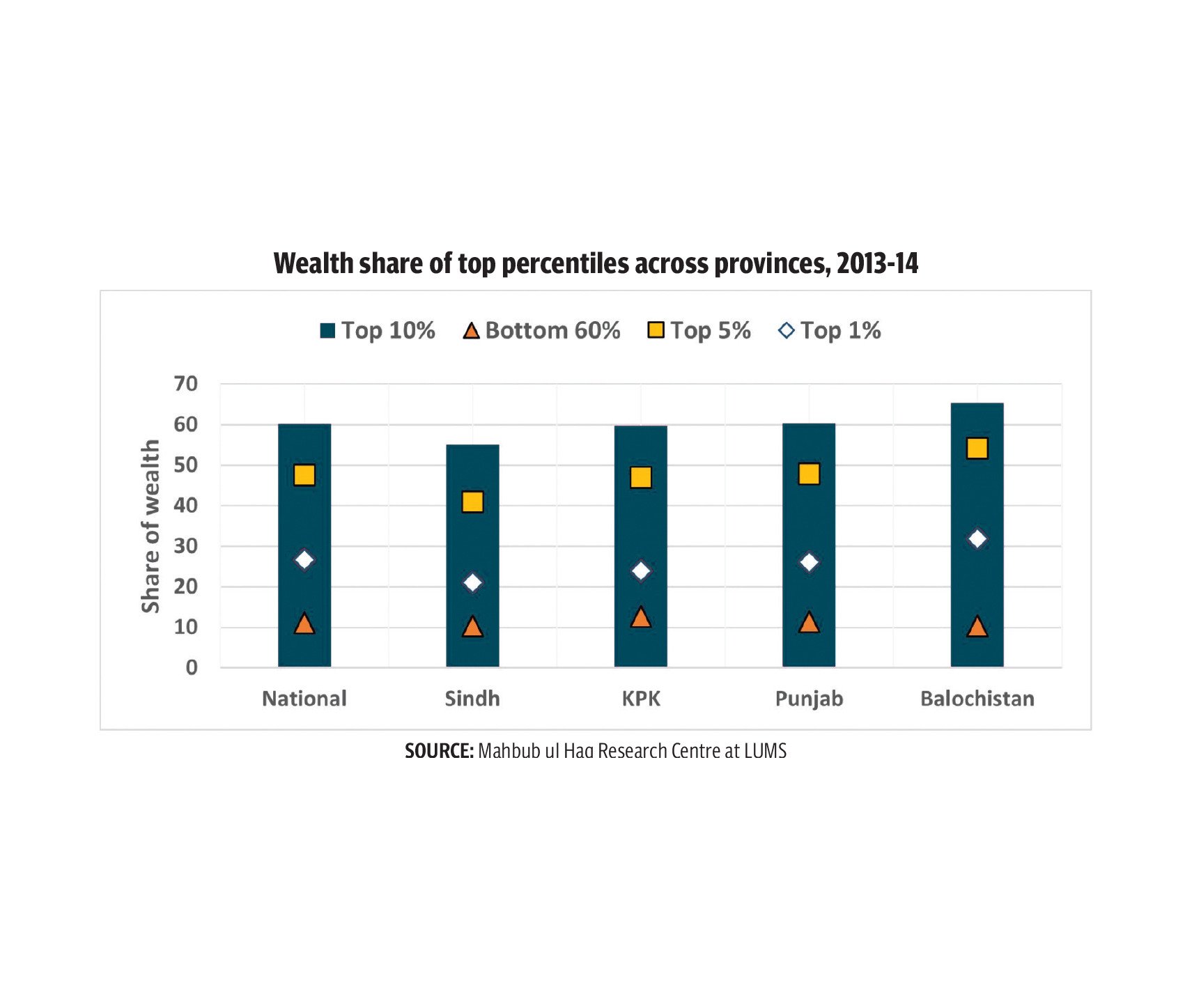

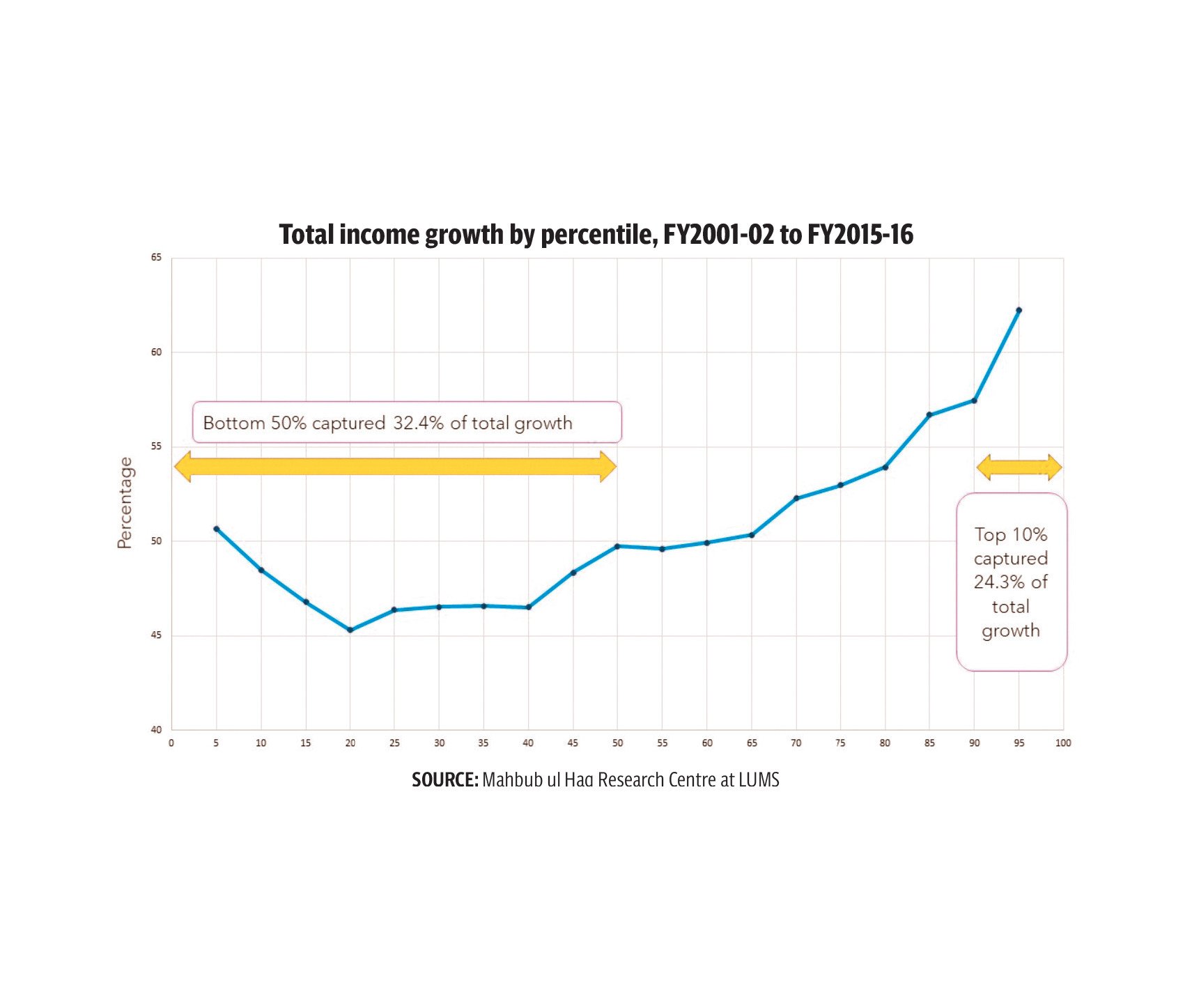

Economic growth is meant to uplift a nation, raising the standard of living for all its people. However, in Pakistan, it often feels like the economic progress is only benefiting a select few. When elite wealth grows faster than the overall economy, capital accumulates, but it doesn't do so in a way that fosters broader growth. Instead of fueling industries that create jobs, innovation, and economic sustainability, Pakistan's wealthiest individuals and institutions are increasingly channeling their resources into non-productive assets — chiefly real estate, but also government bonds, stock market speculation, luxury imports, and offshore holdings. This practice leads to a paradox: while GDP growth stagnates, elite wealth balloons, further exacerbating inequality and hampering the growth of productive sectors that could create long-term prosperity for the nation.

This phenomenon isn't unique to Pakistan. Historically, rapid accumulation of elite wealth paired with sluggish economic growth has often led to asset bubbles and financial crises. For example, the U.S. housing crash of 2008 was spurred by excessive capital flowing into real estate speculation rather than into industries that could create jobs and long-term value. Similarly, Japan's economic bubble in the late 1980s, driven by rampant speculation in stocks and real estate, led to stagnation that lasted for more than a decade. Pakistan mirrors these global trends, where wealth is being accumulated in non-productive sectors, preventing capital from reaching industries that drive sustainable growth.

The real estate trap

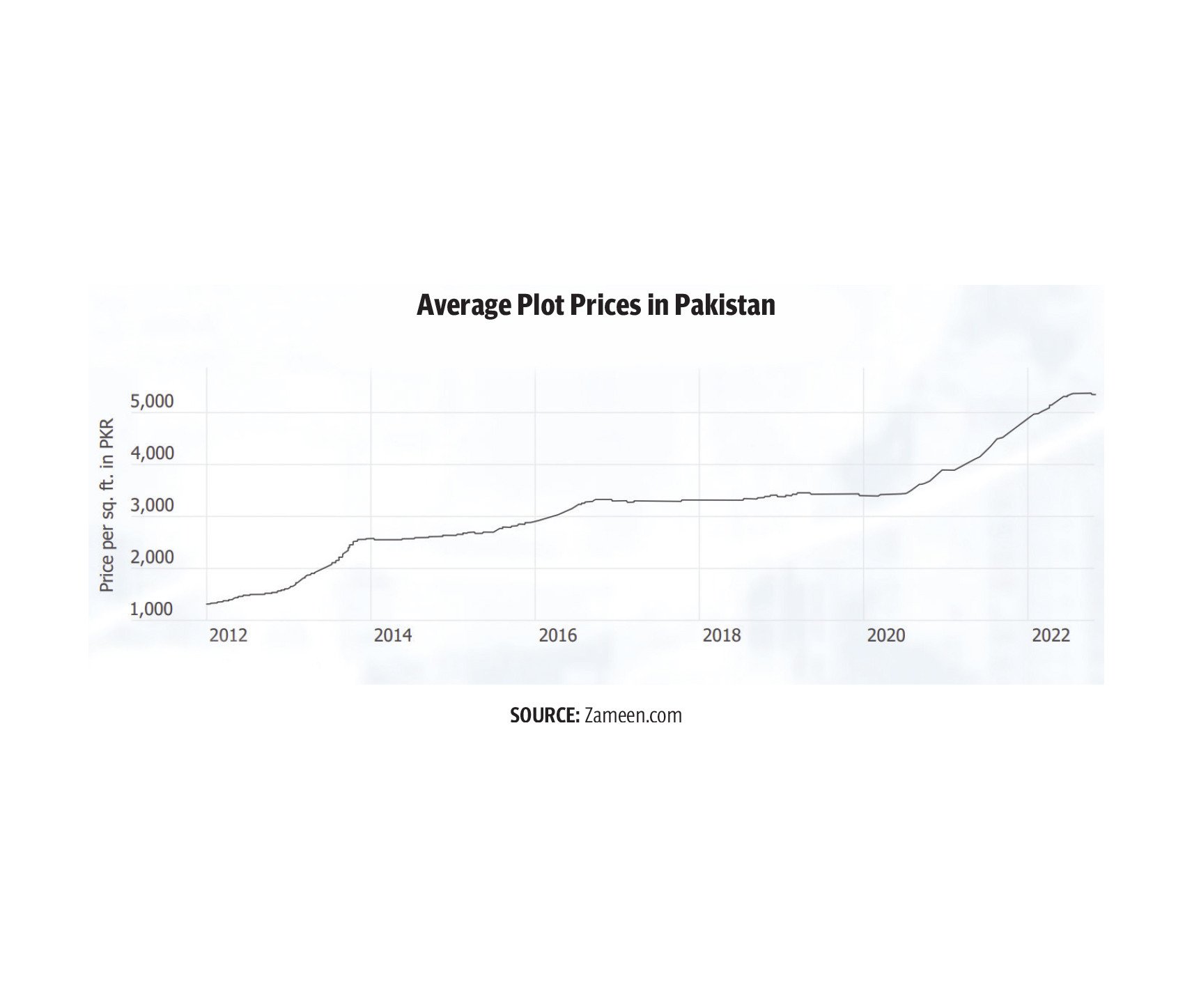

Perhaps the clearest example of capital misallocation in Pakistan is its obsession with real estate. Over the past two decades, land and property have become the primary investment vehicles for the country’s wealthiest individuals and institutions. According to a 2021 State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) study, nearly 60 per cent of all private investment in the country is directed into real estate. This is despite the fact that the real estate sector contributes less than two per cent to Pakistan’s GDP. This imbalance reflects an economy where capital is being hoarded in real estate, rather than being put to work in ways that could drive productivity and economic growth.

Between 2019 and 2022, real estate prices in major cities like Lahore, Karachi, and Islamabad doubled, even as GDP growth languished at an average of just 1.83 per cent. In Lahore, for example, the price of a kanal (a unit of land) in the Defence Housing Authority (DHA) rose from PKR 20 million in 2016 to over PKR 70 million by 2024. Similarly, Islamabad's property values have surged dramatically, even as economic indicators like employment, industrial growth, and exports remain weak. This speculative frenzy is not driven by genuine demand for housing but by elite investors attempting to hedge against inflation and currency depreciation, exacerbating the housing crisis.

The irony of this situation is profound. While the elite amass vast real estate portfolios, Pakistan faces a severe housing shortage of nearly 10 million units, leaving millions of lower- and middle-income families without adequate shelter. Mortgage financing is practically non-existent, with housing finance accounting for only 0.5 per cent of GDP, compared to the 10-20 per cent found in regional economies like India and Malaysia.

Without accessible financing options, homeownership remains an unattainable dream for most citizens, forcing them into overcrowded informal settlements or perpetual renting. Meanwhile, speculative land deals continue to absorb vast amounts of capital, starving more productive sectors — such as manufacturing, technology, and exports — of the investments they need to grow. This misallocation of wealth exacerbates economic stagnation and deepens the country’s wealth inequality.

The Karachi case study

Karachi, Pakistan’s commercial and economic hub, provides a stark illustration of the destructive effects of elite-driven real estate speculation. It is estimated that nearly 45 per cent of Karachi’s land is locked in speculative private holdings, while over 60 per cent of the city's population resides in informal settlements. Land that could be used for industrial purposes, affordable housing, or essential infrastructure remains trapped in elite real estate portfolios, inflating prices without contributing to productive economic growth.

Despite the well-documented harm caused by land speculation, policies in Karachi — particularly those from the Sindh provincial government — continue to incentivise land hoarding. This is in stark contrast to Vietnam’s approach, where an annual 10-15 per cent idle land tax is imposed to prevent the accumulation of unproductive land. Such a policy discourages speculative landholding and forces landowners to either develop their properties or sell them. Unfortunately, Pakistan has not yet considered such measures with any seriousness, continuing to allow speculation to distort the economy.

Capital flight and rent-seeking

Real estate speculation is not the only factor driving the stagnation of Pakistan’s economy. The accumulation of elite wealth has also fueled capital flight, with wealthy Pakistanis sending increasing amounts of money abroad. According to the Pakistan Economic Survey 2023, outward remittances from Pakistan’s wealthy class have increased by over 200 per cent in the past five years. Instead of reinvesting their wealth in local businesses, many of Pakistan’s wealthiest individuals are choosing to park their money in foreign markets, particularly in Dubai’s real estate sector. An estimated $10 billion in Pakistani capital is believed to be invested in UAE real estate alone.

At the same time, rent-seeking behavior among Pakistan’s elite continues to dominate the economy. Rather than investing in startups or expanding industrial capacity, the wealthiest families in the country are increasingly controlling monopolies in key sectors such as sugar, cement, and automobiles. Through cartelisation and anti-competitive practices, these elites are extracting profits from sectors that should be fostering competition and innovation.

For example, the sugar industry in Pakistan is largely controlled by political elites, leading to artificially inflated prices and market distortions. In August 2023, domestic sugar prices surged to PKR 185 per kilogramme, a 110 per cent increase from just ten months earlier. This sharp rise was fueled by government-sanctioned exports and allegations of hoarding and smuggling, leading to domestic shortages despite sufficient production. This rent-seeking behavior stifles competition and discourages investment in industries that could lead to more sustainable economic growth.

A similar issue exists within Pakistan’s stock market. Speculative trading, insider dealings, and capital withdrawals by major investors have led to increased volatility in the market, rather than fostering real business growth. Foreign investment in the Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX) has plummeted in recent years, reaching a historic low of just 3.7 per cent of total market value in 2024, down from nearly 29 per cent in 2017. While the PSX performed exceptionally well in FY24, soaring by 89 per cent in rupee terms (94 per cent in US dollar terms), the underlying volatility and reduced foreign participation reveal deep-rooted issues within the market that prevent long-term growth.

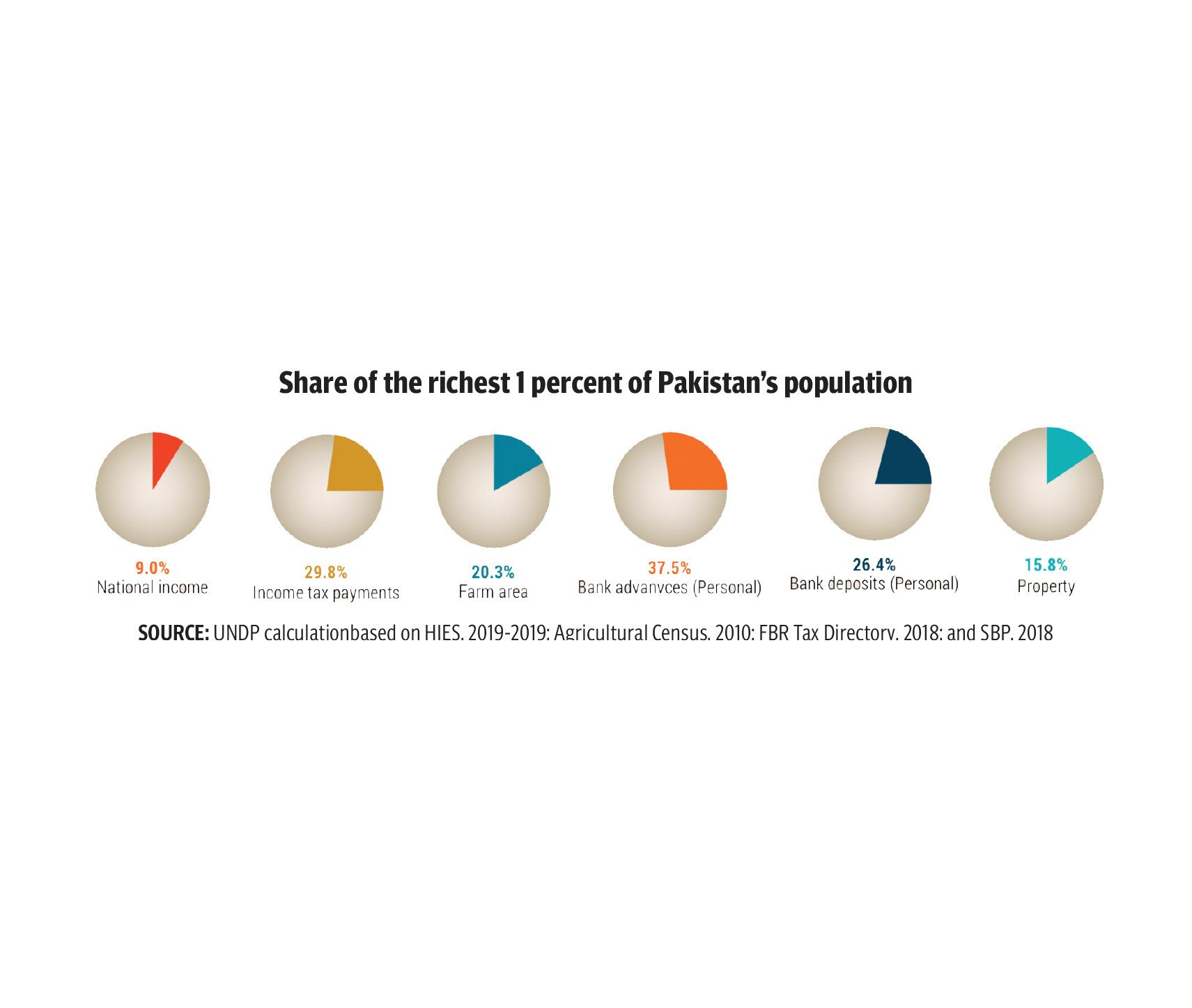

Pakistan’s tax system further exacerbates these distortions. While salaried individuals are heavily taxed, major real estate investors, landlords, and industrialists often benefit from loopholes, tax amnesties, and underreporting. Pakistan’s informal economy, which accounts for nearly 40 per cent of GDP, enables elite capital to operate outside the regulated tax framework, deepening inequality and perpetuating the distortions in the economy.

How Bangladesh avoided Pakistan’s trap

Bangladesh, once lagging behind Pakistan, has successfully avoided falling into the trap of elite-driven stagnation. According to the World Bank, Bangladesh’s GDP per capita grew from $800 in 2010 to over $2,500 by 2022, while Pakistan’s per capita GDP stagnated at around $1,600.

One of the key differences between Bangladesh and Pakistan is the latter’s taxation system. Over the past decade, Bangladesh has implemented progressively higher property taxes on unproductive landholdings and speculative real estate investments. For instance, in 2019, the Bangladesh government introduced a 2 per cent annual tax on unused urban land, alongside capital gains taxes ranging from 15 per cent to 20 per cent on secondary property sales. These taxes have helped to redirect capital into more productive sectors, such as manufacturing and exports.

In contrast, Pakistan’s real estate sector remains largely undertaxed. Despite multiple tax amnesties between 2016 and 2022 — designed to legalise undeclared real estate assets at nominal rates — speculative investments continue to thrive. Between 2020 and 2023, Pakistan collected less than 0.5 per cent of GDP in property-related taxes, while Bangladesh’s revenues from real estate taxation exceeded 1.2 per cent of GDP, contributing to the nation’s impressive growth in productive sectors.

Breaking the cycle

So, how can Pakistan break free from this cycle of elite-driven economic stagnation? Tax reform is the most immediate and necessary fix. A progressive property tax system that discourages land hoarding and speculative real estate investments could push capital into more productive sectors, such as industry, agriculture, and technology.

Pakistan could introduce steep capital gains taxes on second and third properties, impose idle land taxes, and introduce a vacancy tax to deter speculative landholding. India, despite its own issues, has experimented with similar policies in cities like Mumbai, where high taxes on unproductive real estate have helped curb speculation. Pakistan must follow suit if it hopes to unlock capital for investment in industry, agriculture, and technology.

In addition to tax reforms, the government should redirect financial incentives toward industry, technology, and small businesses. Countries like China have actively channeled capital into high-tech industries and infrastructure, spurring long-term economic growth. Pakistan needs similar policies — those that reward industrial expansion, small and medium-sised enterprises (SMEs), and local manufacturing — rather than those that continue to support land speculation and monopolistic rent-seeking.

Reforming the financial sector is also crucial. For example, encouraging bank lending to SMEs, rather than real estate developers, would allow productive sectors to flourish. In Malaysia, SME loans make up 50 per cent of total bank lending; in Pakistan, that number is below 10 per cent. This stark difference reflects misplaced priorities that focus on real estate rather than the sectors that will create long-term value.

Finally, political will is essential. Many of Pakistan’s wealthiest individuals are deeply entrenched in the political system and benefit from the very policies that perpetuate the country's economic stagnation. Breaking the elite capture of the economy requires comprehensive governance reforms, including measures to limit undue influence, enforce fair taxation, and ensure economic policies serve the broader population, not just the elites.

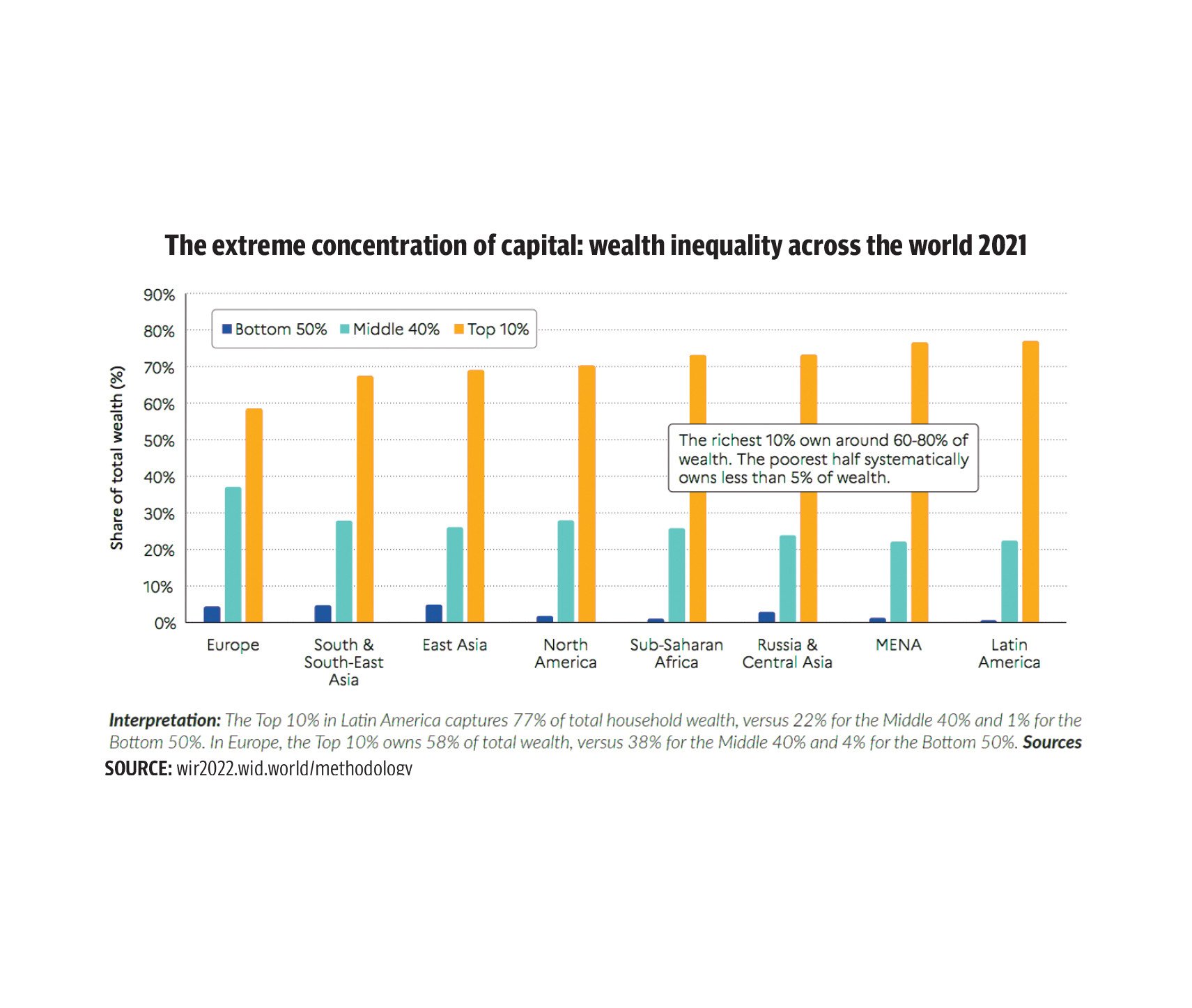

The bottom line is simple: when elite wealth grows faster than the economy, it becomes a drag rather than a driver. Pakistan’s economic future depends on ensuring that capital works for the many, not just the few. If the country does not implement structural reforms to curtail speculative investments, redirect capital into productive sectors, and ensure fair competition, it risks a permanently stratified economy. In such an economy, the rich continue to park their wealth in unproductive assets, the middle class is squeezed out of opportunities, and the country’s full growth potential will remain unrealised. The time for reform is now — before the economy becomes irrevocably trapped in a cycle of stagnation.

Ali Asad Sabir is working as project manager at Mahbub ul Haq research centre at Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS)

All facts and information are the sole responsibility of the author