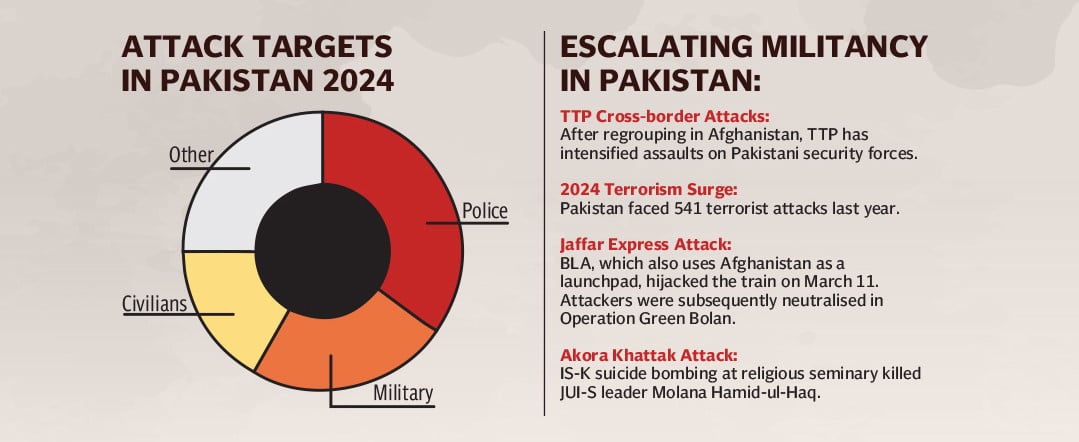

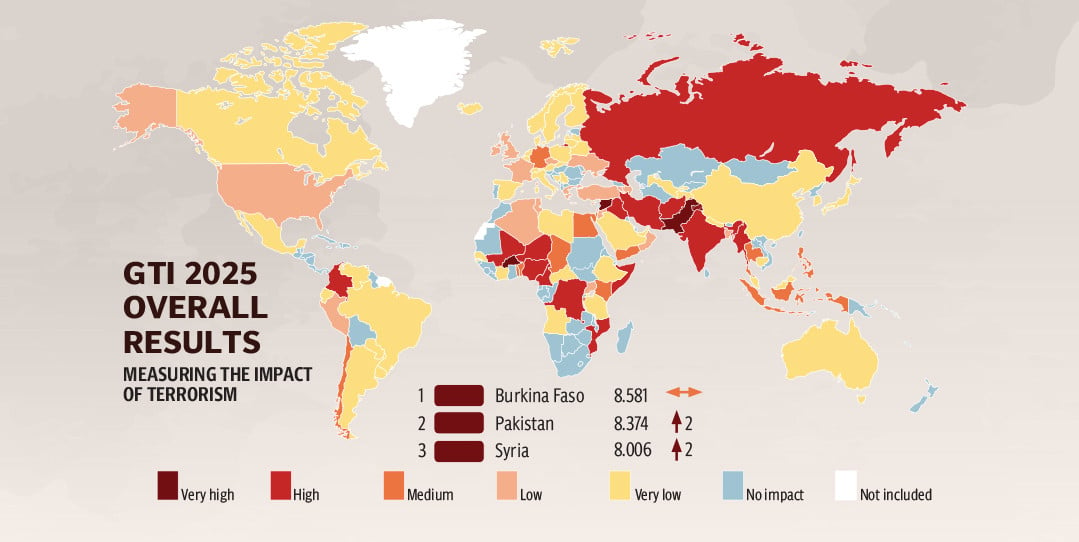

Pakistan is once again trapped in a relentless vortex of terrorist violence, with attacks growing more frequent and lethal over the past two years. The country now ranks second on the Global Terrorism Index (GTI) for 2025, a sharp climb from tenth place in 2022. GTI data shows terrorist attacks more than doubled in 2024, and fatalities saw a 45% surge.

Two volatile provinces — Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (K-P) and Balochistan — bore the brunt of terrorism’s resurgence, accounting for 96% of all attacks and casualties. More than half of the attacks were either attributed to or claimed by the outlawed Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) officially referred to as “Fitna al Khawarij.” The umbrella group was responsible for 52% of all terrorism-related fatalities as it killed 558 people in 482 attacks – a disturbing 91% increase over the previous year.

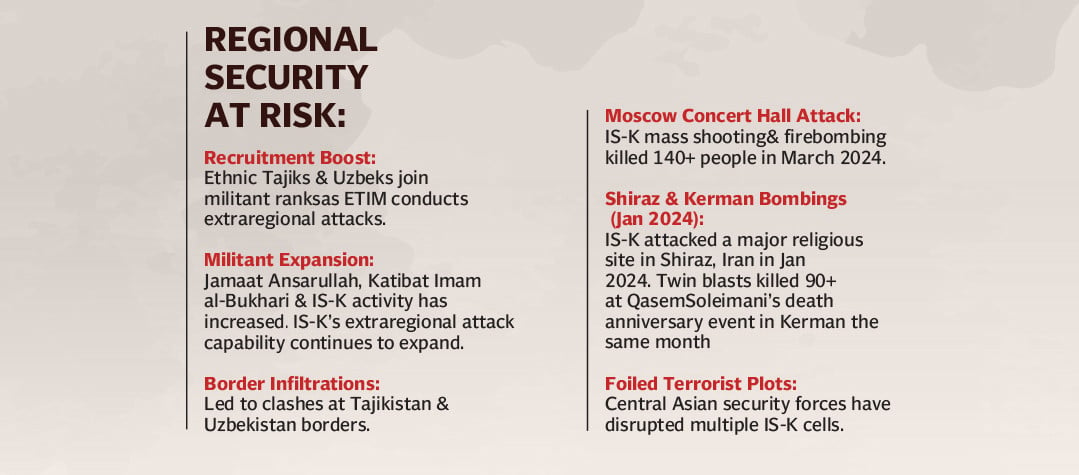

While the TTP’s campaign of terror was concentrated in K-P, two banned separatist groups — the Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA) and the Balochistan Liberation Front (BLF) — intensified their attacks in Balochistan, striking infrastructure, Chinese economic projects, ethnic Punjabi settlers and travelers, and security convoys and installations. Meanwhile, the reemergence of Islamic State-Khorasan (IS-K) marked another alarming shift in 2024, as the ruthless outfit carried out a string of brutal assaults across the country, according to the GTI.

Afghan terror landscape

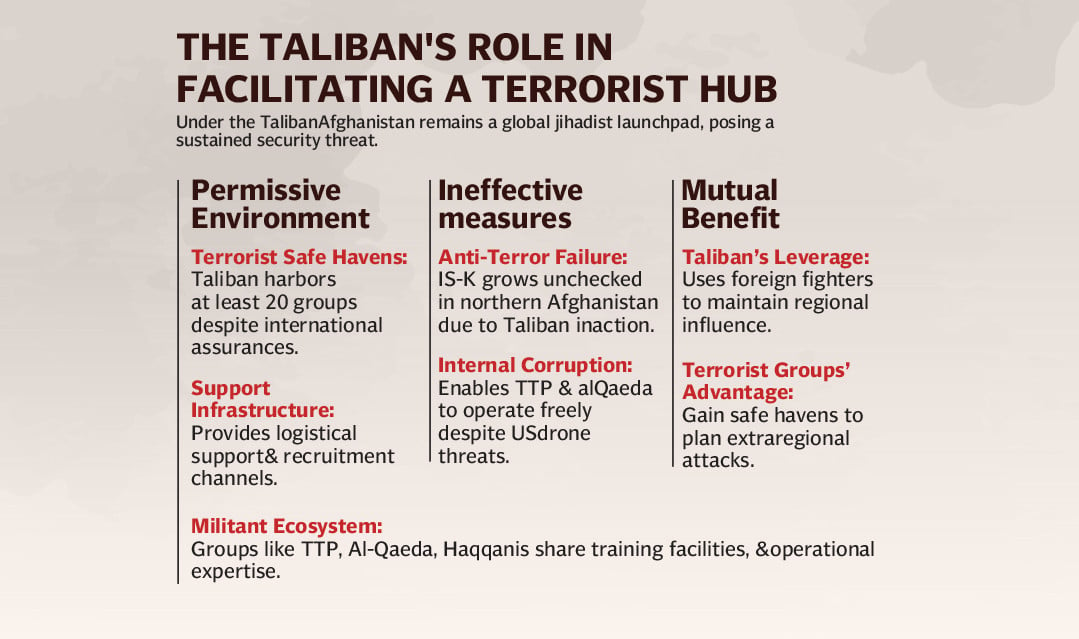

Since the Taliban’s return to power in August 2021, Afghanistan has reclaimed its position as a dizzying melting pot of conflicting ideologies, drawing an array of militant and terrorist groups. Despite their varying agendas, these outfits exist in symbiosis, defined by shared resources, operational coordination, and mutual tactical and logistical support.

According to UN findings, more than two dozen terrorist organisations are currently operating in Afghanistan, fueling instability in the region and beyond. Among the key players in this complex militant ecosystem are Islamic State-Khorasan (IS-K), Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), the Hafiz Gul Bahadur Group (HGB), TTP-Jamaat-ul-Ahrar (JuA), al Qaeda, the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM), Lashkar-e-Islam, Hizb-ut-Tahrir, the Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA), its suicide wing — the Majeed Brigade — the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU), and Tehreek-e-Jihad Pakistan.

Adding to the complexity, more than half a dozen groups — including TTP, TTP-JuA, HGB, and Lashkar-e-Islam — have recently set aside their doctrinal differences to stitch together an alliance of convenience aimed at intensifying attacks in K-P, sources reveal. Surprisingly, al Qaeda and the Ilyas Kashmiri Group have also emerged from relative hibernation to join this ideologically disparate coalition.

Under the new arrangement, Noor Wali Mehsud’s main TTP, backed by LeI and TTP-JuA, is set to focus on Peshawar Valley, as well as the Khyber, Mohmand, and Bajaur tribal districts, sources say. The HGB has been assigned Kurram, North and South Waziristan, and all southern districts of K-P. The Ilyas Kashmiri Group, al Qaeda, and a faction of IS-K are supposed to support the HGB’s violent campaign in these areas.

The HGB is said to have played a pivotal role in uniting the disparate groups, especially IS-K and al Qaeda, despite their deep ideological and doctrinal differences. This alliance could create a potent security challenge for K-P, which is already grappling with a surge in terrorist activity.

The HGB has carried out a series of recent high-profile attacks, including the brazen Bannu Cantt assault earlier this month, which involved multiple suicide bombers. It was also responsible for a similar attack on the same garrison last July. The military said the latest assault was orchestrated and coordinated from Afghanistan in which Afghan nationals were physically involved.

Less than a week later, the banned BLA carried out an unprecedented hijacking of the Peshawar-bound Jaffar Express passenger train in Bolan district of Balochistan on March 11. Officials say all evidence and intercepted communication unequivocally confirmed that the deadly siege was handled from Afghanistan. Some sources claim that the HGB’s Al Hamza Unit of suicide bombers actively aided and abetted the BLA in this attack. The Al Hamza Unit allegedly receives guidance from a senior Taliban intelligence official.

For its part, Islamabad has repeatedly flagged the use of Afghan soil by the TTP and other militant groups for orchestrating attacks inside Pakistan, but the Taliban refuse to acknowledge their presence. Pakistan’s claim, however, has been endorsed by international agencies. The GTI 2025 report states, “TTP’s safe havens in Afghanistan have allowed the group to recruit, organise, and carry out assaults on Pakistani territory, contributing to its expanding operational capability.”

In addition, a UN report covering the period from July 1 to Dec 13, 2024, revealed that the Afghan Taliban continued to provide the TTP with logistical and operational space and financial support, further bolstering the group’s capacity to sustain its violent campaign in Pakistan.

The report, submitted by the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team to the UN Security Council, stated that the TTP has also “established new training centres in Kunar, Nangarhar, Khost, and Paktika provinces” while enhancing recruitment, including from within the Afghan Taliban’s ranks. The report raises alarm over growing cooperation among Afghanistan-based terrorist groups, including “provision of suicide bombers and fighters and ideological guidance,' warning that it could transform the TTP into an ‘extra-regional threat.’”

The Taliban’s chief spokesman, Zabihullah Mujahid, dismissed the report, accusing “specific countries and intelligence circles” within the UN of spreading “false information”.

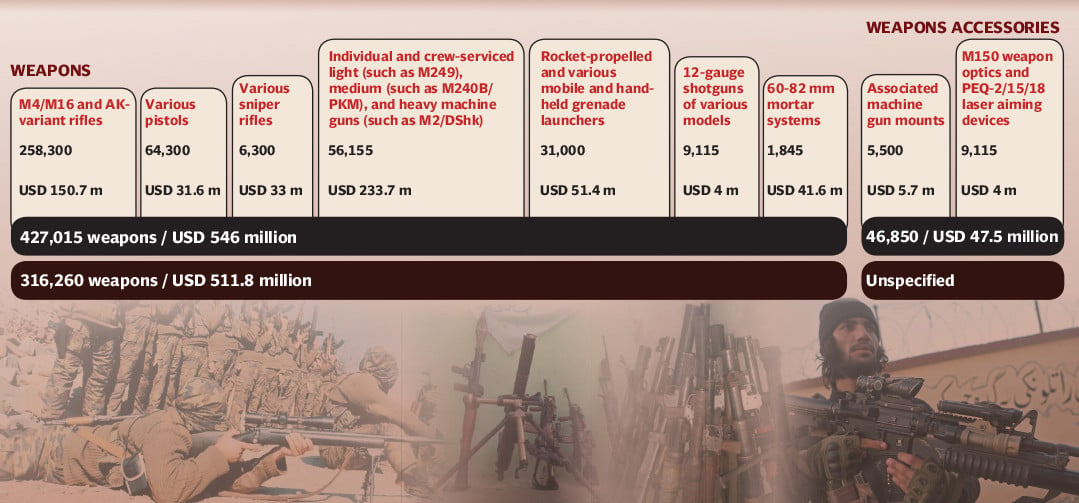

Terror armory

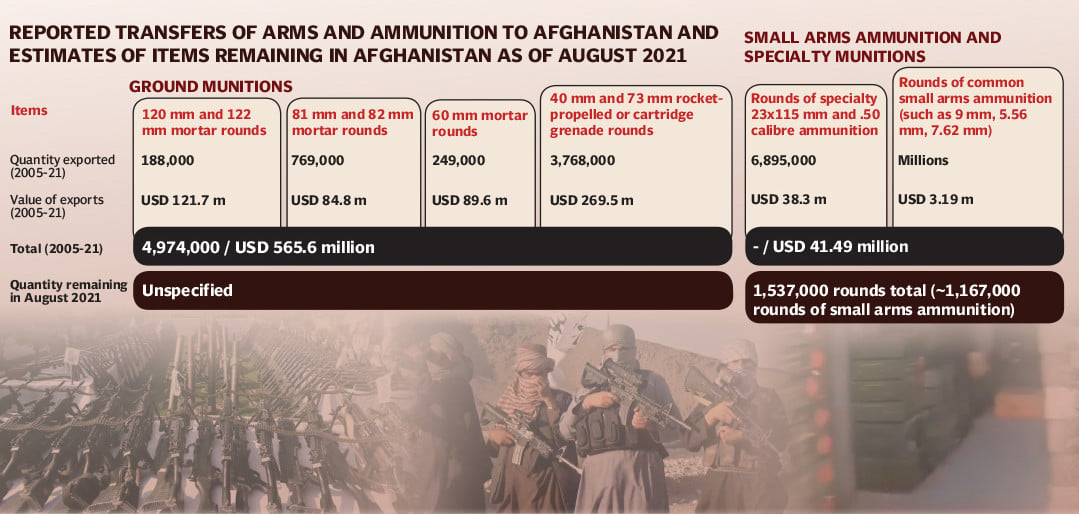

Not only sanctuaries, the TTP and other groups have also gained access to advanced weaponry abandoned by the US forces during their chaotic exit from Afghanistan. According to a joint report by the US Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) to Congress, an estimated $7.12 billion worth of US military equipment was left behind when the Taliban seized power following the collapse of president Ashraf Ghani government in August 2021.

This chest of military equipment – including aircraft, 40,000 vehicles, and 300,000 weapons – has turned the war-torn country into an armory of transnational militant groups. The presence of these advanced arms has made these groups more lethal, enabling them to use their safe havens in Afghanistan’s ungoverned regions as launchpads for terror operations across the region.

Reports suggest that foreign actors, specifically India and Iran, are facilitating the rehabilitation of leftover US weaponry to empower militant networks for their strategic interests. The militarisation of Afghanistan and the unchecked flow of modern lethal weapons are undermining Pakistan’s internal stability, forcing additional military deployments and border security measures at a massive economic cost.

US President Donald Trump has admitted that Afghanistan has become one of the world’s largest sellers of military equipment, using American weapons and vehicles left behind by US forces. “You know that Afghanistan is one of the biggest sellers of military equipment in the world. You know why? They’re selling the equipment that we left,” Trump said during his first Cabinet meeting of the new administration in February. “We’re first. They were second or third. Can you believe it?”

Trump listed the scale of the abandoned hardware, saying Afghanistan now has 777,000 rifles and 70,000 armoured trucks and vehicles, comparing it to the largest used car lots in the US. He said the US should demand the return of its military equipment from Afghanistan. “We left billions — tens of billions of dollars’ worth of equipment behind. Brand-new trucks,” he said. “You see them display it every year on their little roadway someplace where they have a road,” he added. “We’re going to pay them. I think we should get a lot of that equipment back.”

The interim Taliban government has since used the inherited American arsenal not only for governance but also for projecting its military power, suppressing dissent, and harbouring militants with transnational agendas.

The foreign violent groups, the TTP in particular, have benefited the most from the US weapons as they regrouped and rearmed to unleash a renewed terror campaign in Pakistan. Reports suggest that the Afghanistan-based groups now have easy access to small arms, like M4, M16, and AK-47 rifles, explosives and IEDs for use in suicide bombings and targeted assassinations, rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs) used in ambushes, drones for surveillance and attacks, and even armoured vehicles, like US Humvees. Officials say that the TTP, HGB and BLA have increasingly used these weapons for attacks in Pakistan. Afghan nationals have also physically participated in attacks as more than two dozen of them have been killed in security operations.

Compelling evidence

Surprisingly, the Afghan Taliban claim plausible deniability. Their military chief Fasihuddin Fitrat said late last year that “no one can prove the presence of TTP” bases in Afghanistan. Instead, he attempted to shift the blame to Pakistan, accusing Islamabad of using the Taliban as a scapegoat for its “weaknesses and shortcomings”.

However, growing evidence chips away at the Taliban’s narrative. Of late, the Afghan interim government acknowledged that they have relocated some TTP terrorists and their families away from the Pakistan border to the southwestern Afghan province of Ghazni.

But this is just the tip of the iceberg. More incriminating evidence has surfaced. The Taliban’s intelligence agency, the General Directorate of Intelligence (GDI) – particularly its cells 041, 051 and 063 – has not only been arming and bankrolling but also providing cover to the TTP and al Qaeda’s 313 Brigade as well as East Turkistan Islamic Movement (ETIM).

Sources say that Pakistan has intercepted communications showing that a GDI letter dated August 2022 demanded protection for ETIM leader Mullah Abdur Rehman, while another communication revealed a payment of 0.52 million afghanis to slain TTP leader Umar Khalid Khurasani after the fall of Kabul in 2021. The UN report also reveals that TTP chief Noor Wali Mehsud’s family receives around $43,000 per month from the Afghan Taliban, which shows the level of financial support for the terrorist group.

If this is not enough, Taliban’s reclusive supreme leader Sheikh Haibatullah Akhundzada issued a fatwa in August 2023, against Afghan nationals fighting any so-called jihad outside Afghanistan, urging them to stay away from “haram acts of terrorism.” This begs the question: if the TTP is not in Afghanistan as claimed by the Taliban, then what was the need for this fatwa?

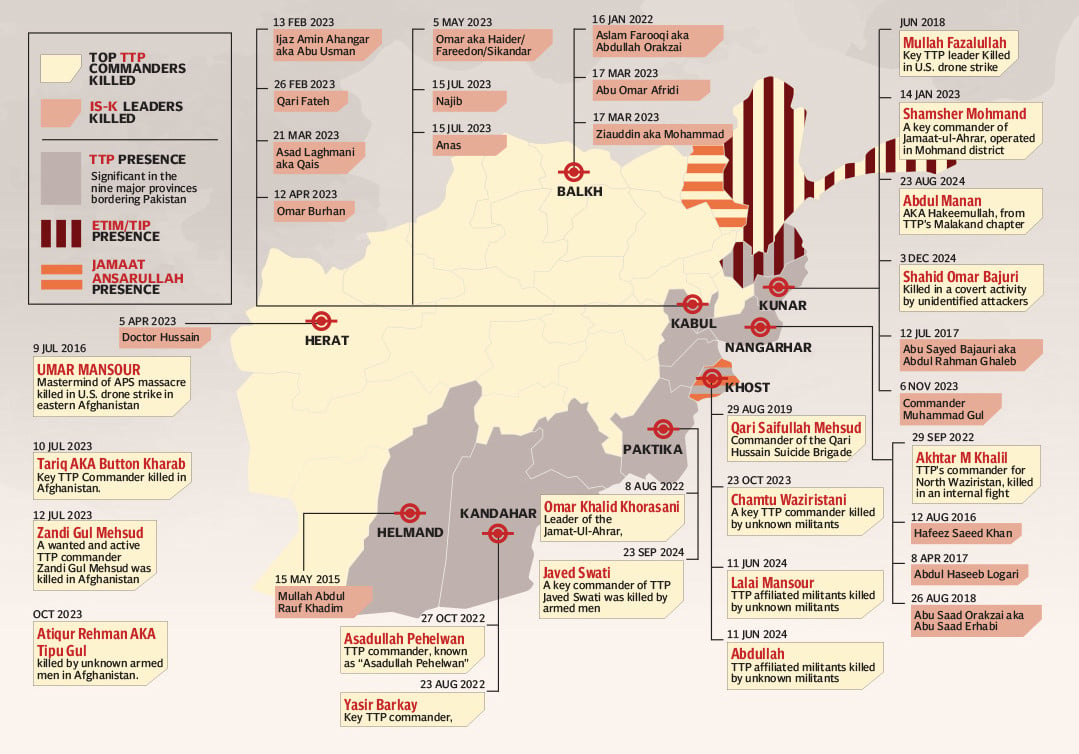

The killing of multiple TTP commanders and fighters on Afghan soil deals another blow to the Taliban’s deniability, making it sound increasingly hollow. Some of key militant commanders killed on Afghan soil included Abdul Manan, aka Hakimullah, Atiqur Rehman, aka Tipu Gul, Omar Khalid Khorasani, Mufti Hassan Swati, Hafiz Dawlat Khan Orakzai, Azam Tariq, Sheikh Khalid Haqqani, Qari Saifullah Mehsud, Mullah Fazlullah, Sajna Mehsud, aka Mullah Haji Mehsud, Shahidullah Shahid, Adnan Rashid, and Gul Muhammad. These killings reinforce Pakistan’s claim that the TTP enjoys safe havens inside Afghanistan. So why do the Taliban persist in denial?

Tug of war

The Afghan Taliban are far from a monolithic entity. There are two major factions – the Kandharis and the Haqqanis – jostling for a bigger share in the power pie. Since Kandhar is the Taliban’s ideological fountainhead and the birthplace of their movement, the Kandharis are hardline ideologues, while the Haqqanis control the fighting machine. Of late, the two factions have been drifting away from each other amid growing distrust. The schisms became more pronounced after the Kandharis started undercutting the Haqqanis by minimising their powers in government ministries. While Sirajuddin Haqqani is the interior minister, the Kandharis ensured appointment of their men as provincial and district police chiefs without consulting the minister in charge. The Kandharis also made sure that the Torkham and Chaman border crossings with Pakistan, a big source of revenue, remain under their control. Similarly, the ministries assigned to the Haqqanis also have a significant number of Kandharis in senior positions.

Another bone of contention is the Haqqanis’ patronage of transnational militant groups, including TTP and al Qaeda. Sources say that al Qaeda operates training camps under the Haqqanis protection. Al Qaeda’s military wing, Katiba Umer Farooq, conducts joint training exercises with the Haqqanis. Elite al Qaeda fighters are also involved in sharing military expertise with the Haqqanis’ suicide units. They have even set up joint camps in the Afghan provinces of Paktia, Khost, and Ghazni to facilitate cross-group recruitment. The Haqqanis also sheltered the TTP and HGB in an effort to repay the two outfits that had fought alongside them against the US-led foreign forces during the insurgency. Paradoxically, the Haqqanis and the IS-K, despite being adversaries, also maintain strategic contacts. Sources indicate that elements within the Haqqanis have mediated between IS-K and the Taliban in targeting former Afghan government officials. IS-K’s foreign recruits often travel through the Taliban-controlled checkpoints, indicating some degree of unofficial facilitation.

These factors aside, the Kandharis and the Haqqanis have divergent viewpoints on several issues that have been undermining their regime’s efforts for global legitimacy. Interior Minister Sirajuddin Haqqani, Foreign Minister Amir Khan Muttaqi, his deputy Sher Mohammad Abbas Stanikzai, and Culture Minister Khairullah Khairkhwa appear to be relatively progressive and pragmatic as they have been pleading for moderation, especially on issues such as girls’ education and working women.

However, the Kandharis, especially Mullah Shireen, Mullah Fazil, Mullah Yaqoob, and Mullah Barader, are regressive ideologues who are least concerned about what the international community says. Speculation has been rife that tensions between the two factions came to a boil a few weeks ago when Sirajuddin resigned from the interior ministry and left the country. However, the Taliban supreme leader asked him to continue because divisions in Taliban ranks would undermine their regime. The Kandharis fear that if worse comes to worst the transnational groups would give the Haqqanis a huge leverage in Afghan power politics.

The TTP factions have also picked sides in this intra-Afghan struggle for influence. This was laid bare by the killing of four TTP commanders in the northeastern Afghan province of Kunar in December 2024. The slain TTP commanders – Rahimullah, aka Shahid Umer Bajauri, Tariq Bajauri, Adnan Bajauri and Khaksar Bajauris – all belonged to the Bajaur tribal district of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa. Shahid Bajaur was TTP’s naib ameer for Malakand Division and carried a Rs10 million bounty. According to sources, the Bajauris suspected the Noor Wali Mehsud-led main TTP for being behind the deadly attack during a feast.

Taliban’s reluctance

Strategists from Pakistan had expected that, once back in power, the Taliban would move to assuage Islamabad’s security concerns by cracking down on militant groups operating from Afghan soil. However, the Taliban remain hesitant, cloaking their inaction in plausible deniability. The question is, why? The answer, it seems, lies in a tangle of shifting dynamics.

First, the Taliban and the TTP are cut from the same cloth; they are two sides of the same coin, with the TTP chief having already pledged allegiance to Mullah Hibatullah Akhundzada. This ideological affinity makes them natural allies in the pursuit of their broader transnational agenda.

Second, the Taliban had received huge support from the TTP during their insurgency against the US-led foreign forces in Afghanistan. Now, the Taliban, being the rulers of Afghanistan, feel obligated to reciprocate by providing them sanctuaries.

Third, the Taliban are hamstrung by resource constraints to launch a decisive action against the well-entrenched groups as they are focused on more pressing challenges of strengthening their nascent regime and addressing a complex array of domestic challenges.

Fourth, the Taliban have accommodated different factions in an effort to maintain internal cohesion. Some of these factions have sympathetic views towards anti-Pakistan groups, such as TTP and BLA. The Taliban fear that any action against these groups could imperil their unity, leading to fragmentation and divisions.

Fifth, the transnational groups are well entrenched and well manned. The Taliban fear that any action could push them, especially al Qaeda, TTP, TTP-JuA, IS-K, and Northern Front, to create a lethal challenge to their fledgling regime akin to the recent successful uprising against the Bashar Al Assad regime in Syria. And lastly, the Taliban may be harbouring anti-Pakistan groups as strategic leverage over Islamabad, viewing them as bargaining chip in future diplomatic dealings with its neighbour.

Empirical data confirms that there has been a significant increase in terrorist attacks in Pakistan since the recapture of Kabul by the Taliban. It also confirms that much of this violence has been perpetrated by the TTP, HGB, and BLA. And there’s consistent evidence that these groups operate from their bases in Afghanistan in an “environment of permissibility” created by the Taliban.

Ideological affinity, reciprocal compulsion, internal political and security dynamics, or strategic interests, whatever may be the motivation behind their plausible deniability, Kabul’s Taliban rulers need to realise that they cannot sweep growing evidence under the rug. They have to act against the anti-Pakistan and other transnational groups operating from Afghan soil and threatening the security of neighbours. In the meantime, Pakistan should also rally the regional states, particularly Iran, China, Russia, Central Asian Republics, and Gulf states, to pile diplomatic pressure on the Taliban regime pushing them to fulfill the commitments they had made in the Doha Accord. Failure to do so on the part of regional players could have broader strategic implications given the regional and extraregional ambitions of these transnational groups.