In the heart of Europe, a pervasive and complex issue quietly shapes the lives of millions – Islamophobia. Far more than an expression of prejudice, it manifests in the everyday realities of discrimination, exclusion, and unequal treatment, profoundly affecting those who identify as Muslim—regardless of their actual beliefs or practices. In a continent where national identities are deeply intertwined with religious and cultural history, the rise of Islamophobia is not merely a social concern but a political and economic one as well.

For many, Islamophobia appears to stem from an irrational fear or misunderstanding of Islam. However, the reality is far more pernicious. It is woven into the fabric of European society, operating in ways that extend beyond hate speech or overt discrimination. Matias Gardell, Professor of Comparative Religion at Uppsala University, has spent years studying this phenomenon. He describes Islamophobia as a form of racism that functions similarly to other racial biases. “It is not just about prejudice or hate speech. It manifests in behaviors, exclusions, exploitation, and systemic inequalities,” Gardell explains.

Gardell’s analysis challenges the common misconception that Islamophobia arises from a fundamental misunderstanding of Islam or a lack of knowledge. Instead, he emphasises that it is not about what Muslims believe, say, or do. “It is not the responsibility of Muslims to act as ambassadors of ‘true Islam’ to correct misconceptions,” he asserts. The issue lies not in the religion itself but in how individuals are perceived—based on their ethnicity, appearance, or simply their association with the Muslim identity.

The impact of Islamophobia in Europe extends far beyond isolated incidents of hate or violence. It permeates various aspects of everyday life, particularly in employment, housing, and healthcare. “If you have a Muslim name, you are less likely to receive a job that matches your qualifications, you will struggle to secure housing in desirable areas, and you will experience unequal access to healthcare,” Gardell notes. The statistics are grim: Muslims in Europe consistently face disadvantages in accessing the same opportunities as their non-Muslim counterparts. Studies reveal that students from Muslim backgrounds often must perform twice as well as their peers to gain the same recognition academically and professionally. This sobering reality underscores the challenges Muslims face in integrating into societies where they are often viewed as outsiders—even when they are born and raised in those countries.

In Sweden, where Gardell conducts much of his academic work, this dynamic is particularly pronounced. “Even if you are born to Swedish Muslim citizens and given a Muslim name at birth, you are instantly marked as an outsider,” he explains. Despite having Swedish citizenship and a strong connection to the country, their perceived Muslim identity places them outside the bounds of full social acceptance. Gardell argues that this identity becomes an inherited essence that prevents integration. “You are born in Sweden yet seen as an outsider.”

To fully understand Islamophobia in Europe, one must recognise its historical context. For centuries, Muslims and Europeans have coexisted, but their relationship has been marred by intolerance and misunderstanding. Gardell draws a parallel to the history of anti-Semitism: “This is similar to how anti-Semitism has historically thrived in places with few Jewish communities.” The effects of this history are still evident today, as Muslims are often seen as foreign, even in countries with deep historical ties to Islam. Gardell points out that Islam’s presence in Europe predates the rise of Protestantism. “There were mosques in Europe 800 years before Lutheran churches appeared,” he says, emphasising that the Nordic region, including Sweden, had contact with Muslim civilisations long before it became a Lutheran nation. This historical connection is often overlooked in modern discussions about Muslim identity in Europe.

Europe’s current anxieties also play a significant role in the rise of Islamophobia. Gardell explains, “There is a sense of civilisational decline among many Europeans. White Europeans who once held global dominance now see their influence waning.” This fear of losing cultural, political, and economic power is compounded by the rapid changes brought about by globalisation, climate change, and migration. “For the first time since modernity, Europe looks ahead and sees an uncertain, even frightening future—climate change, water shortages, forced migration, terrorism, civil unrest, autocracy, corporate dominance,” Gardell notes. These crises have created fertile ground for politicians to tap into a sense of nostalgia for a simpler, more homogenous past. This political nostalgia, according to Gardell, is a reaction to an uncertain future, a longing for the perceived stability of an earlier time. “People do not want to face this reality, so they turn to the past for comfort, engaging in what sociologist Zygmunt Bauman called ‘retrotopia,’” he adds. In countries like Sweden, this nostalgia often manifests as a yearning for a homogeneous Nordic past, “a past where everyone ‘looked like me.’” Gardell argues that this vision of the past is not just a harmless longing but also a “violent act of historical erasure,” one that dismisses the contributions and presence of Muslims and other minority groups in Europe’s history.

Islamophobia, in Gardell’s view, is not merely about religion or culture—it is about power, identity, and the anxieties of a world where European dominance is no longer assured. He draws parallels to historical events like the Spanish Inquisition, which institutionalised the categorisation of people based on their perceived bloodline, labeling them as having ‘Jewish blood’ or ‘Muslim blood’ even if they had converted to Christianity. “This laid the foundation for later racial ideologies that spread through European colonialism, the transatlantic slave trade, and beyond,” Gardell reflects. For many Europeans, accepting these changes has been difficult. As Gardell notes, “Sweden, for instance, went from being one of the world’s most equal societies to one where inequality is rapidly growing.”

Muslim migrants in Europe, especially those from countries like Pakistan and India, often come seeking better opportunities, only to encounter systemic barriers that prevent them from fully integrating. Highly educated migrants in fields like IT or AI may find success, but often only by downplaying their Muslim identity. “If they openly identify as Muslim, they risk being seen as outsiders again,” he notes. This highlights the precarious position that Europe’s Muslim population finds itself in, caught between two identities, neither fully accepted by the society around them.

This sense of alienation and exclusion is often exacerbated by political rhetoric that taps into fears of cultural dilution. Gardell draws parallels between nationalist political movements around the world, pointing to figures like Donald Trump, the Sweden Democrats, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Narendra Modi, and Vladimir Putin. “If you look at Trump—Make America Great Again. If you look at the Sweden Democrats—Make Sweden Great Again. If you look at Erdogan — let’s go back to the Ottoman Empire. Look at Modi talking about shining India, the glory of the Hindu nation... Putin going back to the times where Russia was great and Orthodox,” Gardell says. These politicians, he argues, are all harnessing the power of ‘politicised nostalgia,’ appealing to people’s longing for a time when their countries were seen as powerful and culturally homogenous.

Gardell points out that this global phenomenon of nostalgia is not unique to the West. In both the West and the Muslim world, the longing for a perceived better past can be a powerful political tool, often used to distract from the deep-rooted problems facing societies today. The forces shaping Islamophobia and anti-Muslim sentiment are inextricably tied to the broader challenges of globalisation. As Gardell warns, the current phase of globalisation, dominated by corporate power, is creating ‘dire prospects’ for the future.” With rising inequality, environmental collapse, and a fractured global order, Islamophobia becomes a convenient scapegoat for broader societal frustrations. “We know that if this continues, humanity—if not the planet—will face extinction,” he states, emphasising the urgency of addressing the deeper issues at the root of today’s crises.

In the media, Muslims are often portrayed as outsiders, with stories reinforcing negative stereotypes. “Studies show that more than 100 stories about Islam and Muslims are published daily, covering print, audio, image, and social media,” Gardell notes. However, “Analysis reveals that 9 out of 10 of these stories reinforce negative stereotypes.” Muslims are frequently depicted as part of the problem rather than part of the solution, with only a small percentage of stories offering a more nuanced view. This, Gardell argues, feeds into the larger narrative of exclusion.

Ultimately, Gardell believes that the future of Europe’s Muslim population is one of integration and mutual recognition. “Muslims are not strangers to Europe—that’s a historical fact. In time, they will no longer be perceived as strangers but as neighbors, citizens, and integral members of European societies.” Yet, for this to happen, Europe must reckon with its past and present treatment of Muslims, moving beyond exclusionary narratives to one of true inclusivity. Addressing Islamophobia requires a collective commitment to combat systemic inequalities and challenge the harmful stereotypes perpetuated in the media.

Gardell insists that such a transformation is not only possible but also necessary for the future cohesion of European societies. “If we are to face the challenges of the 21st century—climate change, global inequalities, social unrest—we need unity, not division. Muslims are part of Europe’s future, just as much as any other group,” he argues. The future, Gardell suggests, lies in a more inclusive Europe, where people are judged not by their ethnicity or religious identity but by their contributions to the common good.

“The path to a more just Europe lies not in turning inward or retreating to a mythic past, but in embracing the complexities and challenges of the present, and in doing so, creating a society that is inclusive of all its people,” he concludes.

Troubling trends

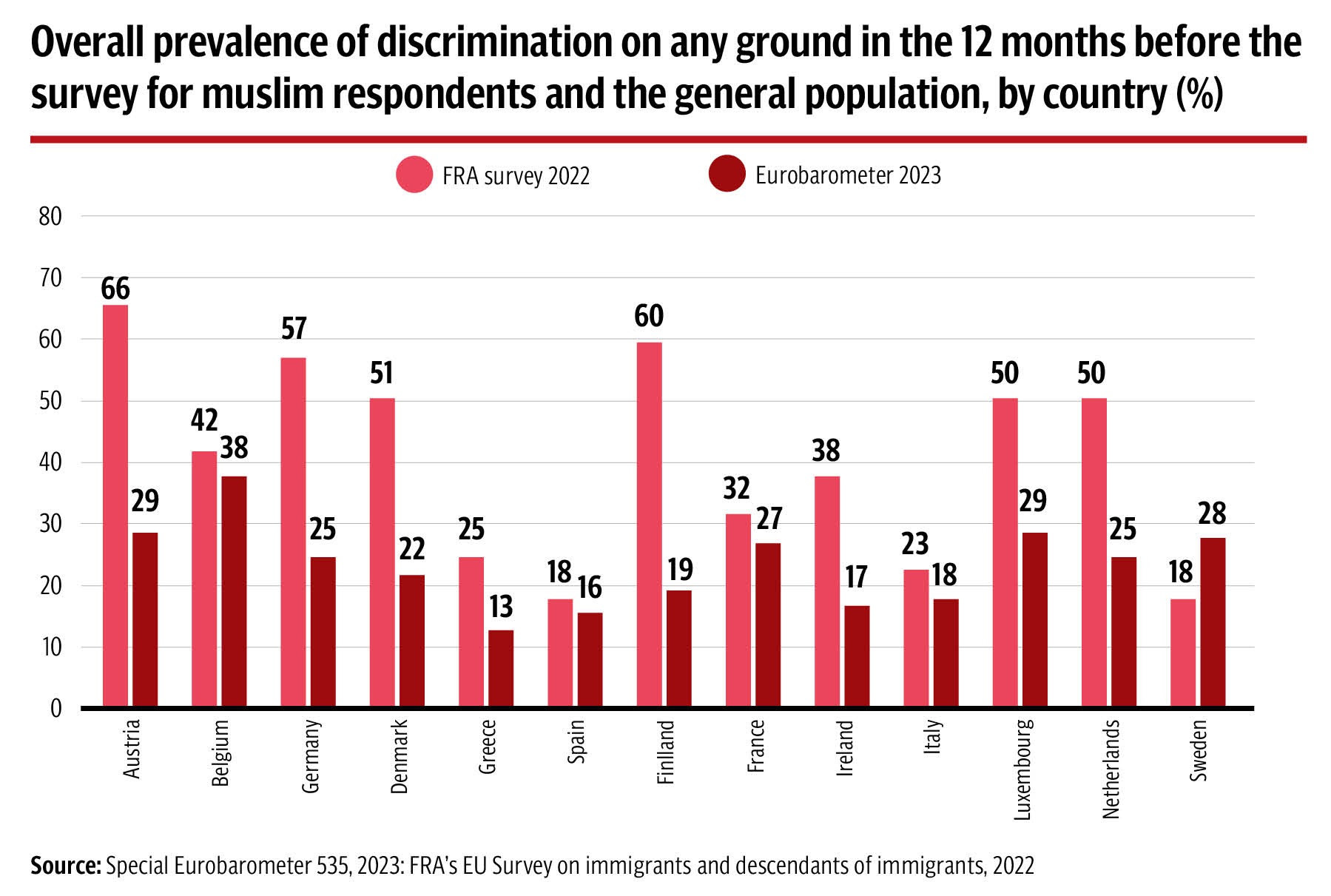

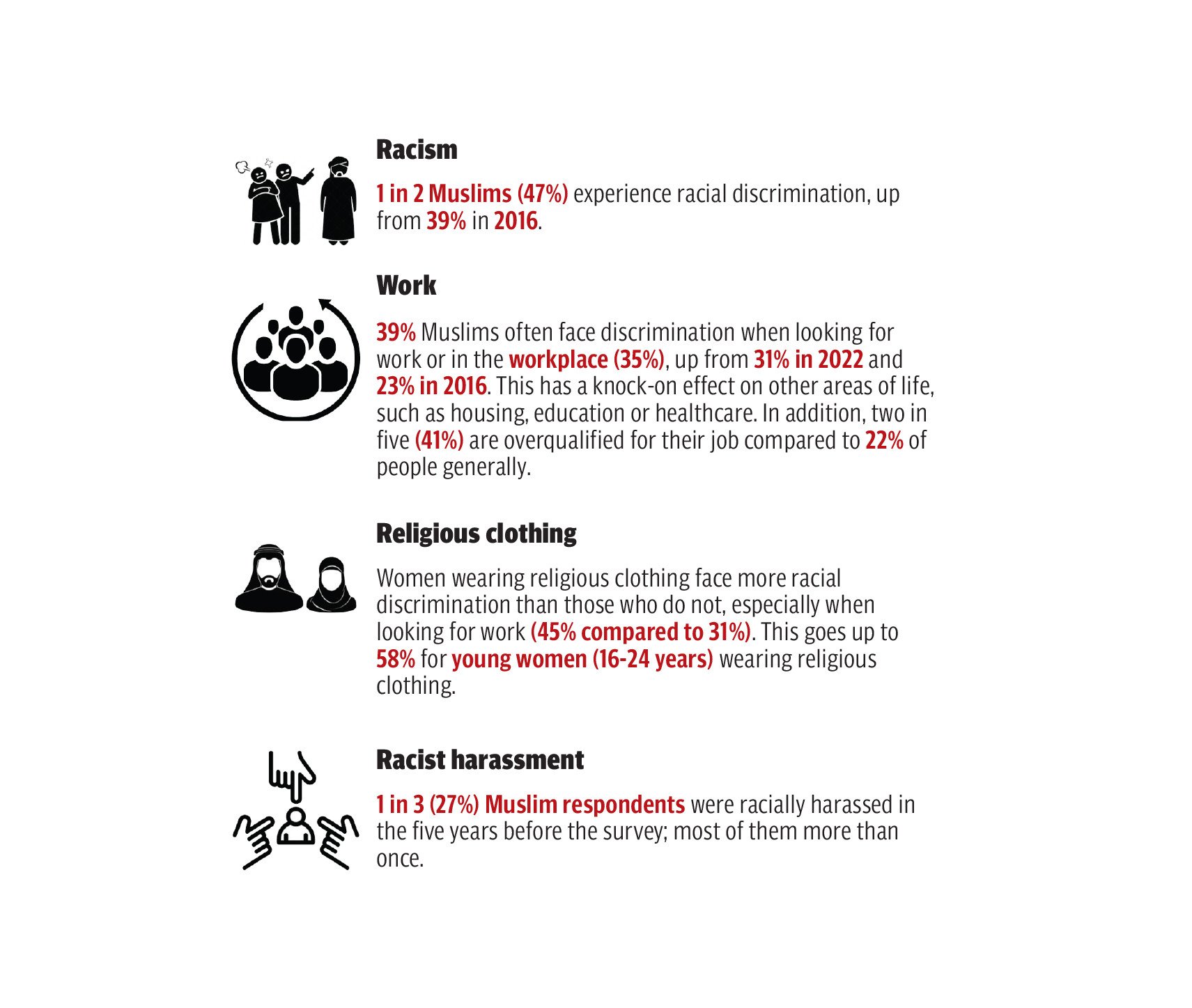

As discrimination against Muslims becomes increasingly widespread, it is evident that this is not a fleeting issue but a pervasive challenge impacting multiple facets of life, from employment and housing to social integration and security. Recent findings from the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) offer a sobering look at the deepening discrimination faced by Muslims across the continent. The agency’s latest report reveals that nearly half of Muslims in the EU report facing discrimination, shedding light on a problem that touches nearly every aspect of their lives.

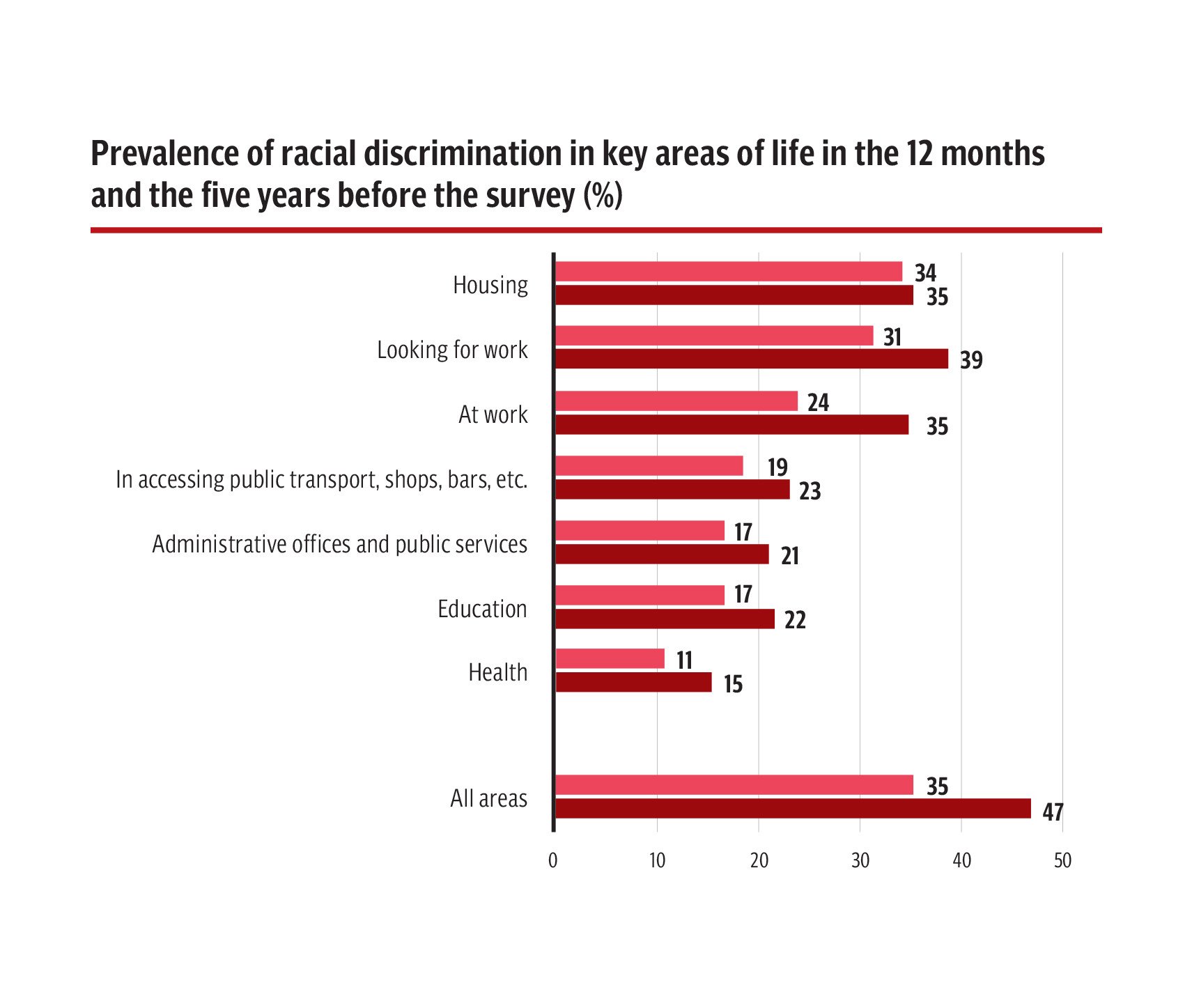

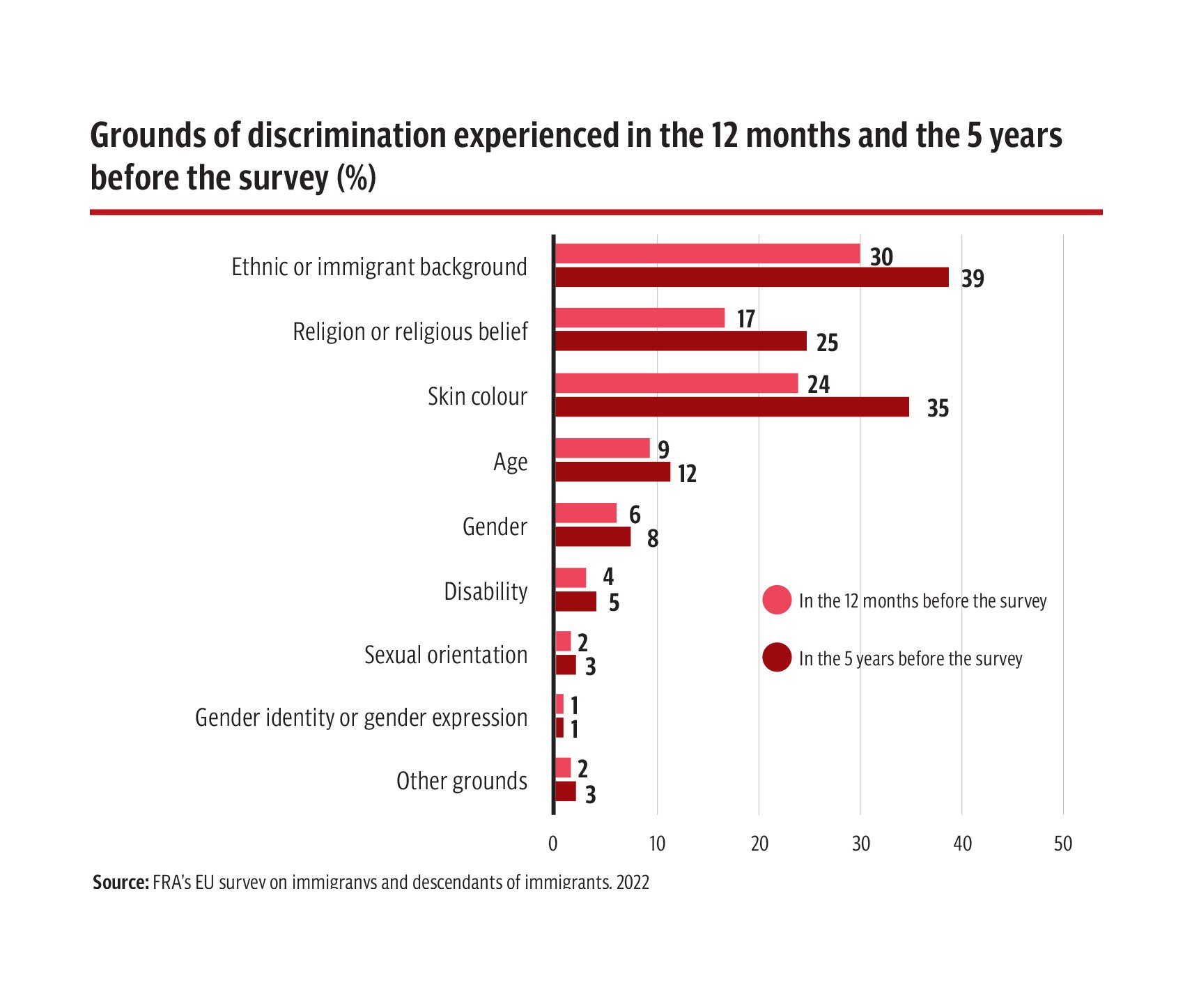

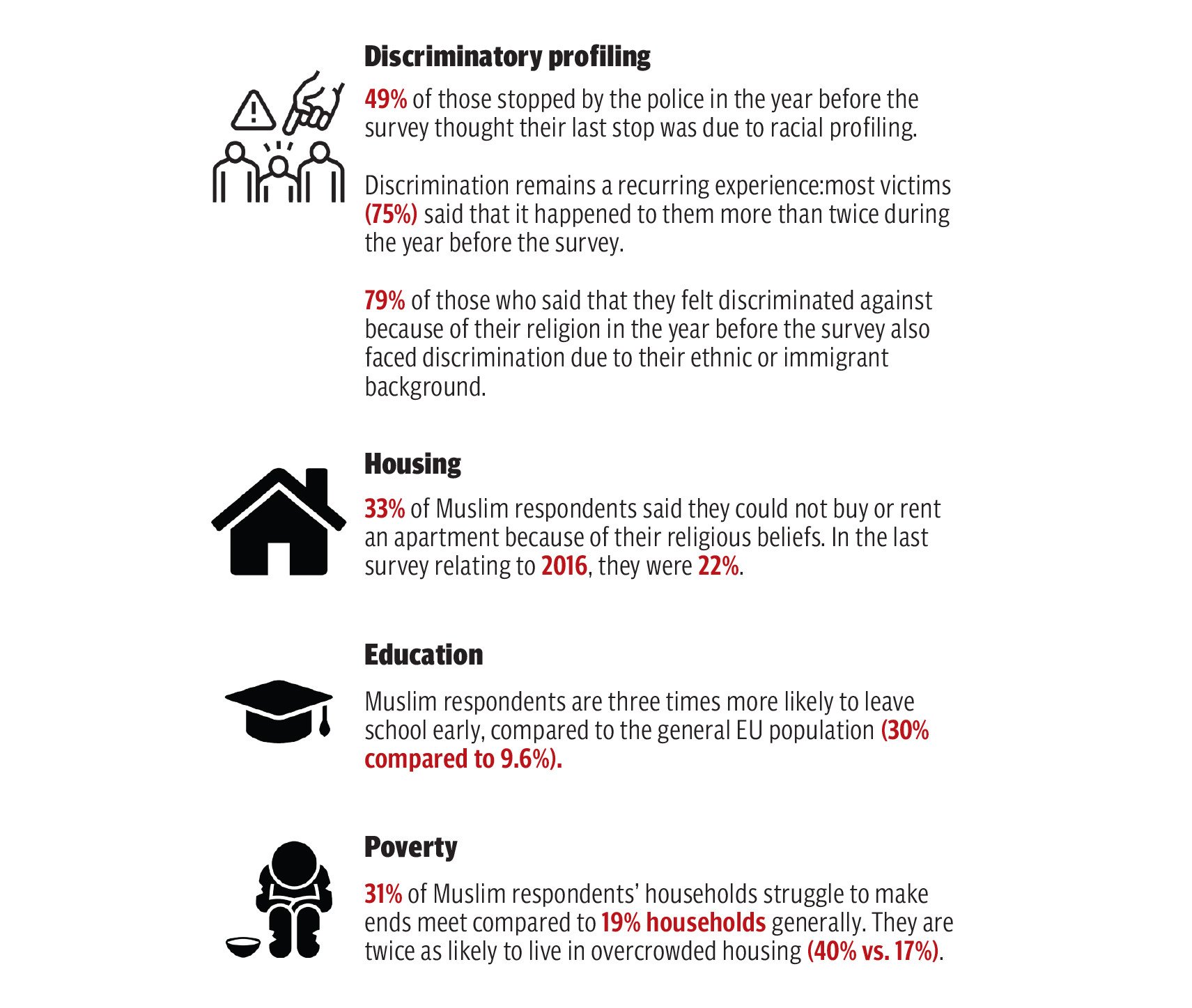

Siobhán McInerney-Lankford, Head of the Equality, Roma, and Social Rights Unit at FRA, emphasised that Islamophobia is not an isolated phenomenon but part of a wider wave of rising discrimination in Europe. “Our reports and survey findings point to rising discrimination, racism, intolerance, and hatred across Europe,” she said. This surge in hostility isn’t restricted to Muslims alone but extends to Jews, Roma, migrants, and people of African descent. Still, for Muslims, the discrimination is particularly entrenched, touching almost every aspect of daily life. FRA’s research reveals that over a third of Muslims experience bias when looking for jobs, at work, or while searching for housing. The scale of the problem shows that anti-Muslim bias is not an occasional issue but a persistent one, shaped by structural forces.

The roots of Islamophobia in Europe are multifaceted, and McInerney-Lankford points to several key factors. Negative public discourse, often fueled by anti-Muslim rhetoric from political figures, plays a central role in exacerbating discrimination. In a climate where divisive and dehumanising rhetoric is commonplace, intolerance becomes normalised, leading to widespread prejudice. “Intolerance and hatred are fueled by many factors, such as conflicts, economic crisis, dehumanising rhetoric used by public figures as well as online hate speech,” she said. This combination of real-world and online forces creates an environment where anti-Muslim sentiment spreads unchecked and even becomes politically mainstream.

The impact of this rise in Islamophobia is not just social—it’s economic and material as well. According to FRA’s findings, Muslims in Europe experience discrimination in ways that restrict their opportunities. Nearly 40 per cent of Muslims reported discrimination in the job market, while 35 per cent faced bias when trying to rent or buy property. These numbers illustrate a troubling trend of exclusion and unequal treatment, where Muslims are forced to confront obstacles that many of their peers do not. The results show that discrimination against Muslims is not just a matter of isolated incidents but a systemic issue that affects their economic mobility. “Muslims in the EU are less likely to work in jobs that meet their level of education and qualification than the general EU population,” McInerney-Lankford said. The undeniable reality is that despite their qualifications, many Muslims are trapped in lower-paying or less secure jobs than they deserve.

Moreover, Muslims across the EU face particular struggles in securing housing, with many reporting that they have been turned away from rental properties or denied the chance to buy homes simply because of their ethnicity or religion. Housing discrimination has long-term effects, creating cycles of poverty and deprivation that are difficult to break. These problems are compounded by living conditions that are often substandard. Muslims are more likely to live in low-quality housing and experience material deprivation, which further isolates them from the broader society.

The discrimination Muslims face is even more pronounced for women, particularly those who wear religious clothing. FRA’s survey reveals that Muslim women experience higher rates of discrimination than their male counterparts, especially in public spaces and in the workplace. McInerney-Lankford emphasised that Muslim women are doubly disadvantaged, as they face both gender-based and religious discrimination. “Muslim women wearing religious clothing or Muslims with disabilities experience even more discrimination and harassment,” she noted. The added layer of discrimination faced by Muslim women highlights the intersectional nature of the problem, making it even harder for them to achieve equality in both the social and economic spheres.

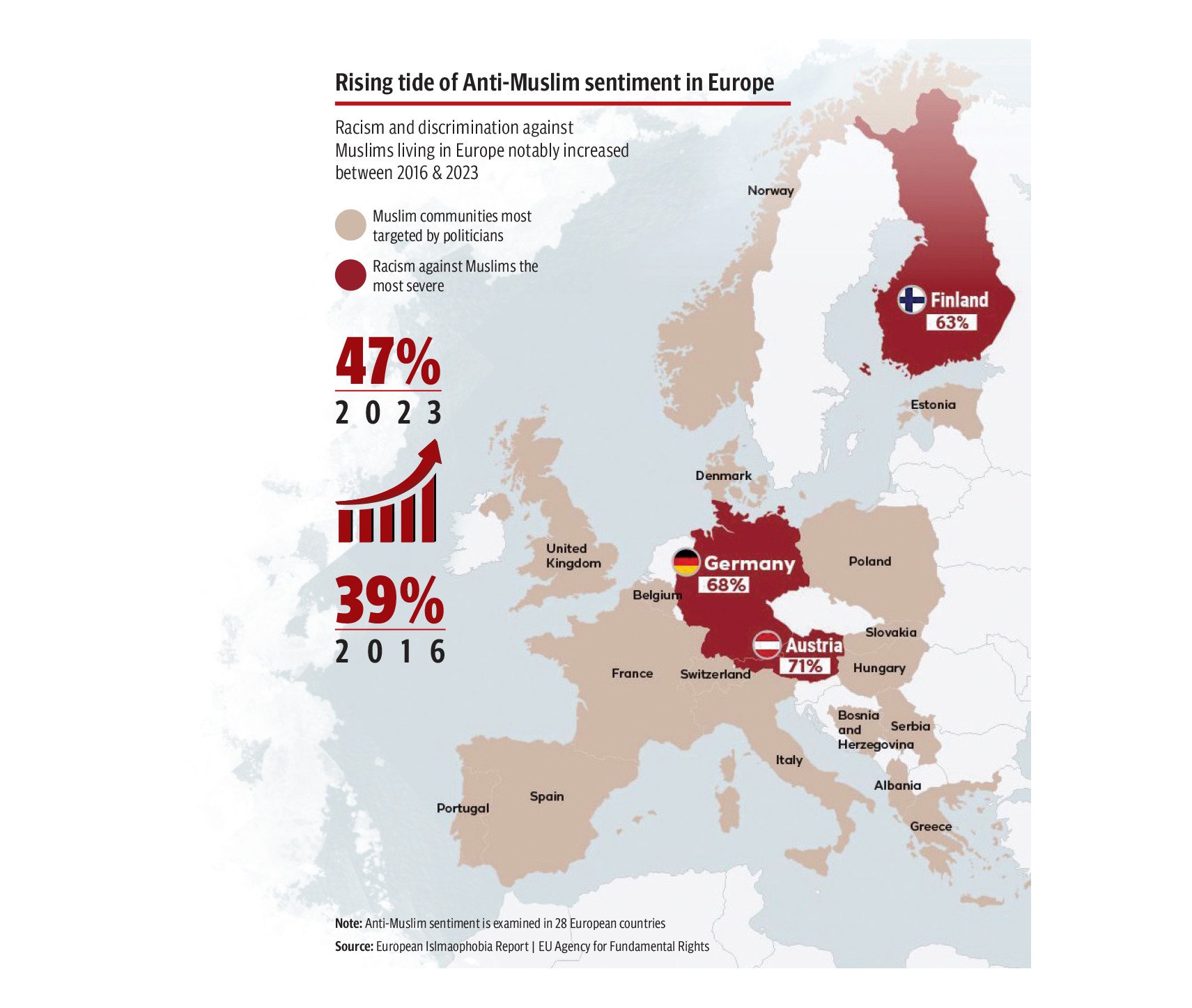

While anti-Muslim sentiment is pervasive across Europe, the situation is particularly severe in certain countries. FRA’s research found that Austria, Germany, and Finland report the highest rates of discrimination, with figures reaching as high as 71 per cent in Austria, 68 per cent in Germany, and 63 per cent in Finland. These statistics underscore the need for action not only at the national level but also across the entire European Union. McInerney-Lankford pointed out that “anti-Muslim racism and discrimination are widespread across all EU countries covered by our survey.” These figures reveal that the problem isn’t confined to isolated nations but is a continent-wide issue that demands urgent attention from policymakers.

In response to this growing crisis, several EU countries have begun to take steps to address the issue. The European Union’s Anti-Racism Action Plan, adopted in 2020, encouraged member states to create national action plans against racism, including anti-Muslim bias. By the end of 2024, 11 EU countries had adopted national plans dedicated specifically to combating racism, and five more were preparing similar measures. However, McInerney-Lankford stressed that these efforts must go further, calling for the renewal of the EU Anti-Racism Action Plan beyond 2025. “We are calling on the EU to renew the EU Anti-Racism Action Plan beyond 2025 and include actions to specifically counter anti-Muslim racism,” she said. This call for a more robust response underscores the ongoing need for coordinated action to tackle anti-Muslim bias across Europe.

Social media platforms have also become a major factor in the spread of Islamophobia. FRA’s research shows that online hate speech is rampant, particularly targeting women and minority groups. “Abusive comments, harassment, and incitement to violence easily slip through online platforms’ content moderation tools,” McInerney-Lankford explained. This allows hateful rhetoric to proliferate unchecked, feeding into existing prejudices and creating even more divisions in society. To combat this, the EU has introduced the Digital Services Act (DSA), which places new requirements on social media companies to assess and address the risks posed by online hate speech. However, McInerney-Lankford emphasised that the solution requires cooperation from multiple stakeholders, including the platforms themselves. “Efforts by various stakeholders, including platforms, are needed,” she said, acknowledging that the EU’s legislative measures alone will not suffice.

The Israel-Gaza conflict has also exacerbated anti-Muslim sentiment in Europe. Reports from Germany and Sweden show a marked increase in anti-Muslim hate incidents in 2023, particularly in the wake of the Hamas attacks. McInerney-Lankford confirmed that FRA had observed a spike in discrimination against Muslims after these events. “We are aware of reports from several EU countries, highlighting a spike in anti-Muslim hatred after the Hamas attacks,” she said. This uptick in Islamophobia shows how international events can fuel local tensions, leading to increased violence and discrimination against Muslims living in Europe.

Framing the reality of Islamophobia

Islamophobia is often framed as a byproduct of Western anxieties—an issue confined to Europe and North America, exacerbated by right-wing populism, security discourses, and migration crises. Salman Sayyid, Professor of Social Theory and Decolonial Thought at the University of Leeds, challenges this narrow understanding by arguing that Islamophobia should be recognised as a global system of racialisation that transcends both geographic and ideological boundaries. His work, particularly in Recalling the Caliphate, situates Islamophobia not as a simple matter of cultural bias or religious intolerance but as a racialised form of governance that regulates ‘Muslimness.’

For Sayyid, Islamophobia functions as a form of racism, even if Muslims are not traditionally categorised as a racial group. He critiques the dominant discourse that reduces racism to a matter of individual prejudice, instead emphasising that racism operates as a structural mechanism of exclusion and regulation. “Racism does not refer to the existence of ‘races’ but rather a process of racialisation,” he explains, arguing that Islamophobia is not about hostility toward Islam as a religion but about controlling expressions of Muslimness. This distinction, he notes, is often lost in the way Muslim-majority countries have sought international recognition for Islamophobia—framing it as religious discrimination rather than a systemic model of racial governance. “One of the mistakes made by many Muslim countries who have sought to get UN and other international recognition of Islamophobia is that they have tried to understand it as religious discrimination rather than racism that targets not ‘Islam’ but Muslimness.”

Sayyid also pushes back against the notion that Islamophobia is uniquely European or a phenomenon exclusive to the political right. Instead, he describes it as a global logic of exclusion, evident in diverse ethno-nationalist movements. “Forces of Hindutva, Zionism, white supremacy, Burmese nationalism, Kemalism, and Han chauvinism all articulate their visions of the future through Islamophobia,” he argues, positioning it as a defining feature of multiple nationalist projects rather than a singular ideological bias. His framing connects the anti-Muslim policies of the European Union—such as hijab bans or counterterrorism measures—to policies in India, China, Israel, and even Muslim-majority states, where governments have instrumentalised Islamophobia for political legitimacy. “Laws and norms that restrict Muslim participation in society, anti-terrorism measures targeting Muslimness, and policies on immigration create a hostile environment for expression of Muslimness, and this becomes normalised as political opinion.”

This argument extends into his critique of media narratives. Sayyid suggests that mainstream discussions around Islamophobia often focus on its media representation rather than its structural function. “The media is as much an effect of global Islamophobia as its cause,” he notes, explaining that media discourses do not simply construct anti-Muslim sentiment—they reflect and amplify an already existing system of exclusion. His comparison between the framing of Muslim refugees and Ukrainian migrants, for example, underscores how Islamophobia shapes public discourse by normalising certain forms of exclusion while legitimising others. “The media reports a migration crisis because it is Islamophobic. Pakistan, Iran, and Turkiye have hosted between 10-15 million refugees for decades. When hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians crossed into the European Union following the Russian invasion, the media did not describe this as a migration crisis.”

Similarly, Sayyid resists the idea that Islamophobia is a product of right-wing nationalism alone. He points to an upcoming conference titled Islamophobia: Beyond Left and Right as an indication that anti-Muslim sentiment is embedded in broader political and ideological structures. “Islamophobia is not exclusively a right-wing phenomenon,” he asserts. “Regimes and societies that tend towards ethno-nationalism will see in Muslimness an obstacle. Islamophobia can be found in the members of the OIC, as well as the European Union, United States, India, Burma, Tel Aviv, and wherever ethno-nationalism is promoted.” His argument suggests that Islamophobia functions across the political spectrum, shaping policies and narratives in ways that go beyond conventional left-right binaries.

Perhaps most strikingly, Sayyid challenges the language of ‘radicalisation’ as a framing device used to delegitimise Muslim political agency. “The current use of the term ‘radicalisation’ is itself a symptom of the normalisation of Islamophobia,” he argues. By positioning Muslim demands for justice or political participation as ‘radical,’ this discourse limits the scope of legitimate Muslim political engagement, treating expressions of resistance as inherently suspect. “It is not radical to find that there is a gap between what a society claims and what it delivers, it is not radical to demand justice, it is not radical to demand the end of discrimination.” Rather than seeing opposition to Islamophobia as extremism, Sayyid reframes it as a struggle for liberation. “The existence of Islamophobia limits the agency of Muslimness, but the struggle against Islamophobia requires political mobilisation. This is not radicalisation, it is liberation.”

His perspective, then, demands a fundamental shift in how Islamophobia is understood—not merely as a problem of individual bias or policy excesses but as a global structure of racial governance that actively regulates and marginalises Muslimness.

Europe’s relationship with Islam

For centuries, Muslims have been cast as the ‘other’ in the European imagination, a perception reinforced by historical events such as the Catholic Reconquista of al-Andalus. This long-standing narrative has defined Muslim communities as outsiders, alien to European culture and values. Following post-World War II migration waves, this framing took on a racial dimension, with Muslims increasingly depicted not only as cultural threats but also as challenges to Europe’s secular, liberal identity. The terrorist attacks of September 11 and the rise of groups like ISIS further entrenched this perception, linking Islam with violence in the public discourse. As a result, the exclusionary narratives that have shaped Europe’s relationship with Islam for centuries continue to manifest in policies and public debates today.

In Norway, these narratives have taken root within the country’s political and social landscape, says Sindre Bangstad, researcher at the Institute for Church, Religion, and Worldview Research (KIFO). Bangstad, whose 2014 book Anders Breivik and the Rise of Islamophobia examines the ideological roots of far-right extremism in Norway and Europe, argues that Islamophobia in Norway is part of a broader European trend fueled by populism.

“The far right’s growing prominence in Norway is not an isolated phenomenon,” Bangstad says. “It’s tied to the broader political shifts across Europe, where anti-Muslim sentiment has become a central mobilising force for populist movements.” The political landscape in Norway, he explains, has been shaped by such forces, particularly with the rise of groups like Stop the Islamisation of Norway (SIAN). While SIAN’s public Qur’an burnings and other provocative actions have drawn widespread condemnation, Bangstad views them as symptoms rather than the root cause of Islamophobia in Norway.

“The real and tangible threat is coming from the populist right-wing Progress Party (FrP),” he says, noting that the party has long capitalised on anti-Muslim rhetoric and is poised to play a major role in government after the September 2025 elections. Although SIAN commands limited public support, its tactics—chiefly, invoking free speech to justify provocative acts—have been effective in mainstreaming Islamophobic rhetoric. Norwegian liberal elites, Bangstad notes, were initially complicit in this mainstreaming.

“When SIAN first started burning Qurans in public, it was enough for them to shout ‘free speech’ to receive widespread media coverage,” he says. “Only later did Norwegian media start to backpedal, realising that SIAN’s actions were not about free speech but about pushing a far-right, racist agenda.”

Despite these challenges, Bangstad remains optimistic about the resilience of Norway’s Muslim communities, who have responded to Islamophobic provocations through democratic and peaceful means. “Norwegian Muslim umbrella organisations have been very clear in advocating that SIAN’s acts are best countered not with counter-demonstrations but through peaceful dialogue,” he explains. This approach, he says, has promoted interreligious dialogue and mutual respect, demonstrating a constructive way to resist Islamophobia.

The broader European context, however, suggests that anti-Muslim sentiment is becoming further entrenched. The spread of far-right ideologies such as the “Eurabia” and “great replacement” theories into the political mainstream has created an environment in which Islamophobia is increasingly normalised. Bangstad points to the role of influential figures in amplifying these narratives. “When people like Elon Musk start endorsing far-right talking points in Europe, it gives legitimacy to these exclusionary discourses,” he warns. “If we take seriously the idea that the protection of minorities is essential to democracy, then we must recognise that democracy in Europe is currently under very real and existential threat.”

The 2011 terror attack in Norway, carried out by right-wing extremist Anders Breivik, stands as a grim reminder of the consequences of Islamophobic rhetoric merging with violent extremism. Bangstad underscores how Breivik’s manifesto reflected a broader ideological trend that has persisted in far-right circles. “As academics working in this field have long noted, there can perfectly well be Islamophobia without the actual presence of a mass of Muslims,” he says. “The far-right is ascendant in many European countries, and the future of conviviality is under severe threat.”

Bangstad also highlights the role of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in shaping Islamophobic narratives. He notes that Breivik “held great admiration for Israel” and viewed it as an ally in the “war against Muslims.” This reflects a broader trend in far-right discourse, where support for Israel is often framed not as solidarity with Jewish people but as a strategic alignment against Muslims. “In this rhetorical set-up, righteous Muslim anger at Israel’s serial violations of international law and human rights is routinely stigmatised as ‘anti-Semitic,’” he says.

Another key issue is the racialisation of Muslims in Norway. While Muslims from Southeast Asia and the Middle East frequently face racial discrimination, Bosnian Muslims—who arrived as refugees from the 1990s Balkan conflicts—have largely avoided similar treatment. This uneven experience, Bangstad notes, highlights the contradictions within Islamophobia. “It’s a contradiction-laden process,” he says. “More and more Muslims in Europe are succeeding in higher education and the workforce, challenging stereotypes and reshaping what it means to be Muslim in Europe.”

As Europe grapples with the rise of Islamophobia and the mainstreaming of far-right ideologies, Bangstad’s research underscores the need for a fundamental reassessment of European identity. “The challenge isn’t just about countering extremist rhetoric,” he says. “It’s about rethinking what it means to be part of Europe and who gets to be included in that vision.” For countries like Norway, where the far right continues to gain ground, the stakes are high. “The threat from the mainstreaming and sanitising of the exclusionary discourses of the extreme right by populist right-wing actors in Europe will remain with us for the foreseeable future,” Bangstad warns.

Weaponising fear

In an era of heightened global tensions, the stigmatisation of Muslim communities has become a pervasive force, often framed in ways that hinder their integration into broader societies and deepen their exclusion. This growing marginalisation is not confined to any single region or ideology but reflects a widespread, systemic issue. Dr. Ineke van der Valk, an independent researcher focused on racism, Islamophobia, and extremism, highlights that Muslims in the Netherlands are facing increasing stigmatisation, which is often framed to undermine their integration and contribute to their exclusion. She emphasises that the rise of anti-Muslim sentiment is not the result of isolated incidents but is intrinsically linked to larger geopolitical events and media-driven narratives that shape public opinion globally.

Dr. van der Valk traces the roots of rising Islamophobia in Europe to a series of key events, both domestic and international. The 9/11 attacks set in motion a chain reaction that fueled negative views of Muslims, particularly in the West. This sentiment was further intensified by the global war on terror and critical incidents such as the murders of politician Pim Fortuyn in 2002 and filmmaker Theo van Gogh in 2004. “The murder of Pim Fortuyn in 2002 and the assassination of Theo van Gogh in 2004, alongside their media coverage, were pivotal in shaping Dutch public opinion,” Dr. van der Valk explains. These incidents, particularly van Gogh’s murder, catalyzed fear and suspicion towards Muslims, with the media portraying the attackers as emblematic of a broader threat from Islamic radicalism.

The growing migration of Muslim-majority populations to Europe, including the Netherlands, has also fueled anxieties about cultural identity and integration. While migration has long been part of European history, recent waves—driven by conflict and economic hardship in countries like Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan—have made the Muslim presence in Europe more visible. Dr. van der Valk notes that these demographic shifts have provoked concerns, particularly in the Netherlands, which has traditionally prided itself on liberal values and secularism.

She argues that the media and political figures, particularly within right-wing populism, have deliberately amplified these fears. Figures like Geert Wilders, leader of the far-right Party for Freedom (PVV), have framed Islam as an ideology incompatible with Dutch values. Wilders and others have effectively weaponised fears surrounding Islam and immigration to galvanise political support among voters who feel alienated by demographic changes.

“The extreme right has increasingly taken control over the public discourse, obscuring the real situation with its real problems, policy options, and solutions,” she states. One of the most effective tools in this strategy is the so-called ‘invasion myth,’ which portrays Muslim refugees and migrants as an existential threat to Europe. Dr. van der Valk argues that this rhetoric is rooted in cultural anxieties rather than any substantial evidence of a threat posed by Muslim communities.

These narratives are no longer confined to political elites. The rise of social media has enabled far-right ideologies to spread further and faster than ever before. Online platforms have become fertile ground for amplifying Islamophobic messages, recruiting supporters, and organising hate campaigns. “Social media has allowed for the rapid dissemination of Islamophobic views,” Dr. van der Valk explains, noting that the internet has become a powerful tool for spreading misinformation.

Traditional media also plays a central role in shaping public perceptions of Islam and Muslims. While the press reflects societal prejudices, it also actively contributes to Islamophobic narratives. Sensationalist coverage often emphasises fear and division over nuance, with stories on terrorist attacks frequently highlighting the Muslim background of perpetrators while ignoring broader contexts or diversity within Muslim communities. “The press both reflects societal prejudices and actively contributes to anti-Muslim narratives,” Dr. van der Valk states.

She also highlights the role of politicians like Wilders in shaping the media’s focus. His rise to prominence, she argues, was largely fueled by extensive media coverage of his inflammatory statements, which helped push his views into mainstream discourse. Despite the growing visibility of Islamophobic sentiments, Dr. van der Valk believes change is still possible. While the hardening of attitudes towards Muslims may seem inevitable, she remains hopeful that these trends can be reversed through social and political shifts, as well as more inclusive policies