In a small village in rural Pakistan, a young mother named Shahida* lies on a charpoy, her body wracked with pain as she clutches her swollen abdomen. She has been suffering from severe stomach cramps for days, but with no healthcare facilities nearby, she has been forced to rely on the advice of unqualified traditional healers. Her husband, a daily wage laborer, has taken a day off from work to take her to the nearest hospital, but they know it will be a long and arduous journey, with no guarantee of quality care at the end of it.

Shahida’s story is not unique. Millions of Pakistanis, particularly women and children, suffer from preventable illnesses and injuries due to lack of access to quality healthcare. In urban areas, the situation is not much better. In Karachi's Lyari neighborhood, for example, residents are forced to navigate narrow alleys and crowded streets to reach the nearest hospital, which is often understaffed and underfunded. The air is thick with pollution, and the smell of garbage and sewage hangs heavy over the streets. It is a bleak and unforgiving environment, where the struggle to survive is a daily reality.

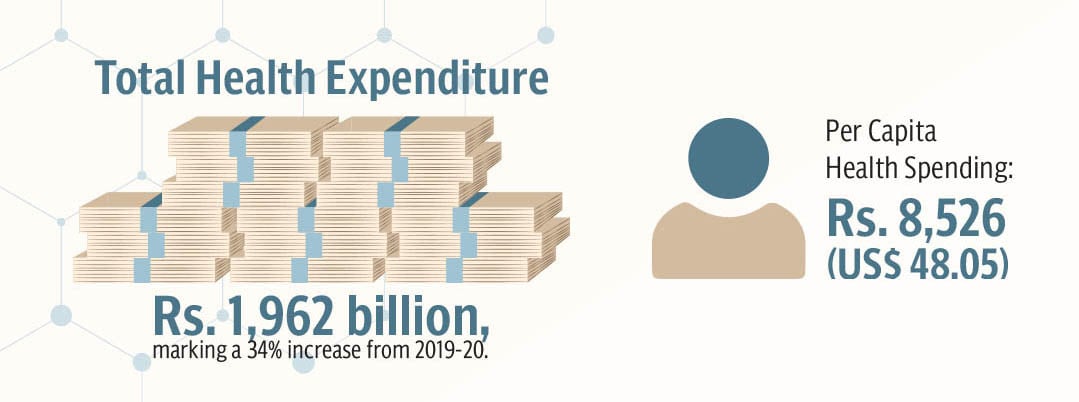

Pakistan, a country of over 220 million people, is facing a healthcare crisis of epic proportions. Despite being the fifth most populous country in the world, Pakistan's healthcare system is woefully inadequate, with millions of people struggling to access even the most basic medical care. The statistics are staggering, Pakistan has one of the lowest healthcare expenditures in the world, with only 2.9 per cent of its GDP allocated to healthcare. This translates to a per capita health spending mare Rs8,526, which is equivalent to $48.05, compared to the global average of $1,064. This is also lower than the World Health Organisation's (WHO) recommended level of $86 per capita. The result is a healthcare system that is underfunded, understaffed, and ill-equipped to meet the needs of its rapidly growing population.

The consequences of this crisis are far-reaching and devastating. Every year, thousands of Pakistanis die from preventable diseases such as tuberculosis, malaria, and diarrhea. Maternal and child mortality rates are among the highest in the world, with over 170 mothers dying for every 100,000 live births, and over 69 children dying before their fifth birthday. The lack of access to healthcare is exacerbated by poverty, inequality, and social injustice, with the poor and marginalised bearing the brunt of the crisis. In rural areas, where healthcare facilities are scarce and often non-existent, people are forced to rely on unqualified traditional healers or travel long distances to access medical care.

Despite these challenges, there are glimmers of hope on the horizon. The government of Pakistan has launched several initiatives aimed at improving healthcare access, including the Universal Health Coverage Act 2024, which promises to provide health insurance to all citizens. Meanwhile, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) are working tirelessly to provide quality healthcare services to those who need them most. Here is a different Pakistan, one where healthcare is not a privilege reserved for the wealthy, but a fundamental human right available to all.

Struggling to keep pace

Pakistan's healthcare system is in a state of crisis. With a population of over 220 million people, the country's healthcare infrastructure is woefully inadequate, leaving millions of people struggling to access even the most basic medical care.

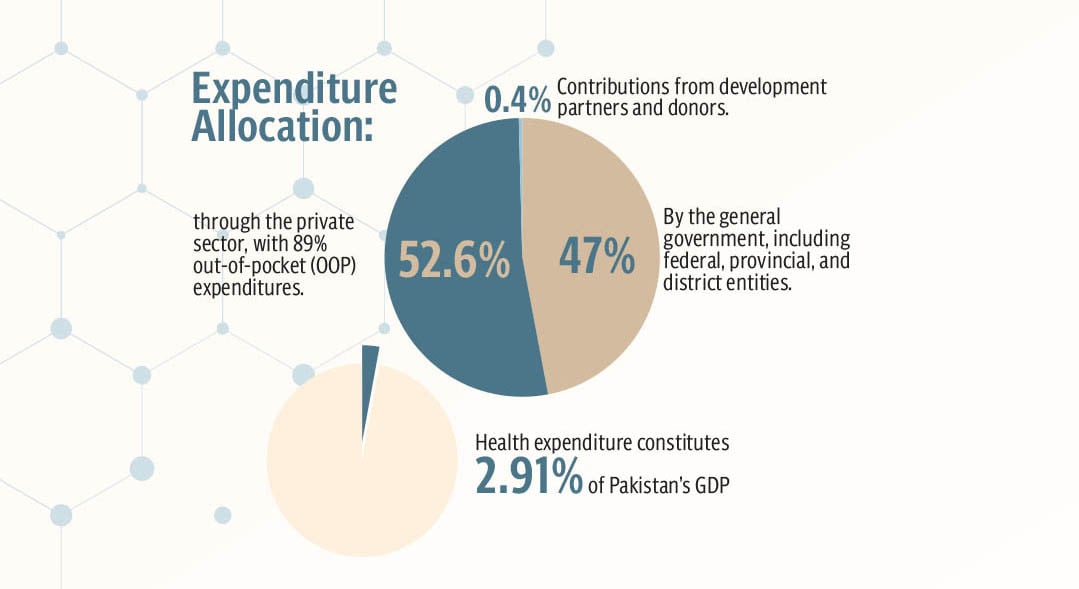

According to National Health Accounts Pakistan 2021-22, total health expenditure was Rs. 1,962 billion, marking a 34 per cent increase from 2019-20. Per capita health spending was PKR8,526 (US$ 48.05). Expenditure allocation was 47 per cent by the general government, including federal, provincial, and district entities, whereas 52.6 per cent through the private sector, with 89 per cent out-of-pocket (OOP) expenditures, while 0.4 per cent contributions from development partners and donors.

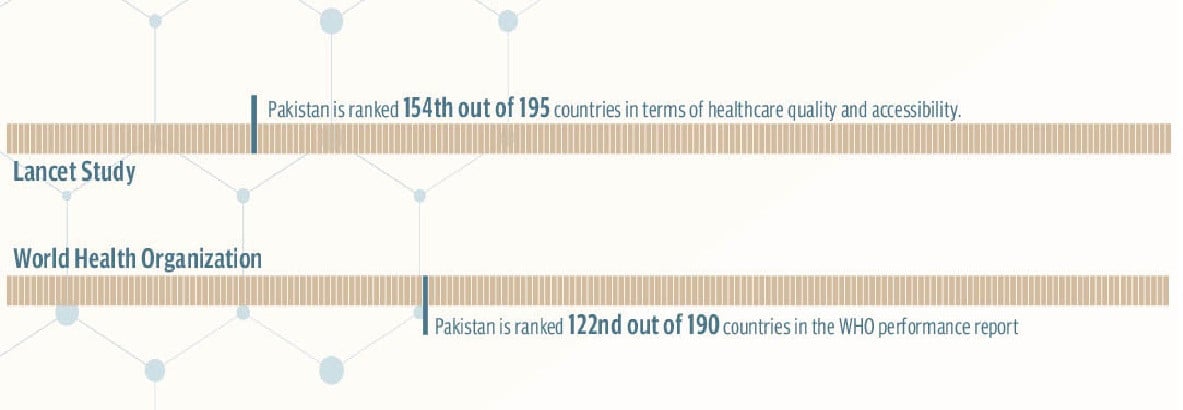

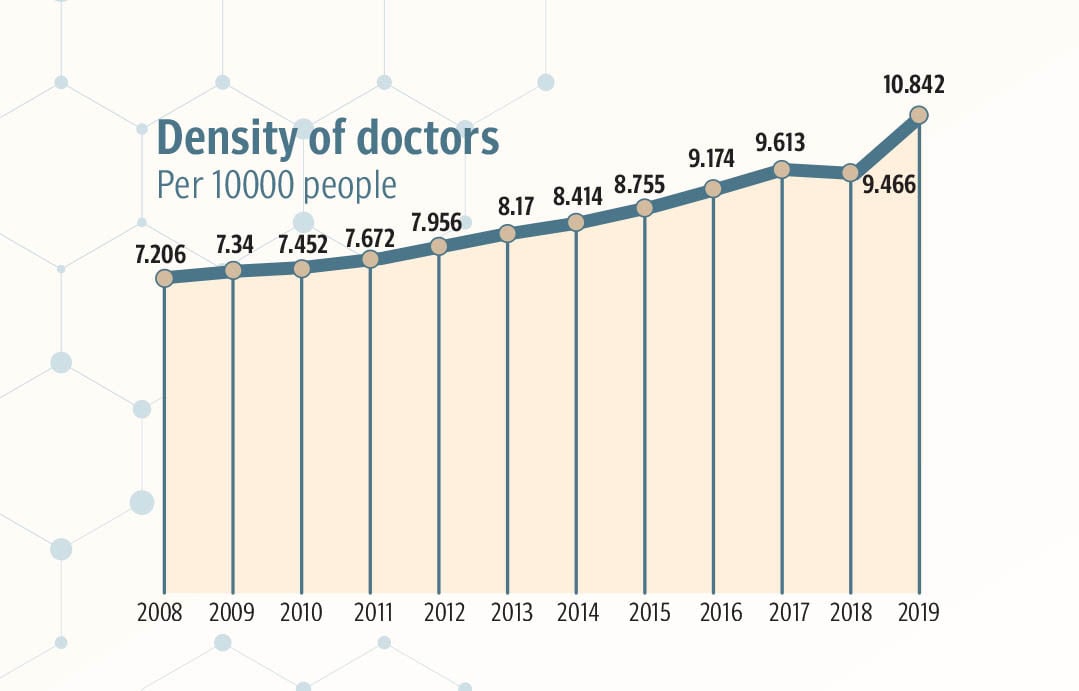

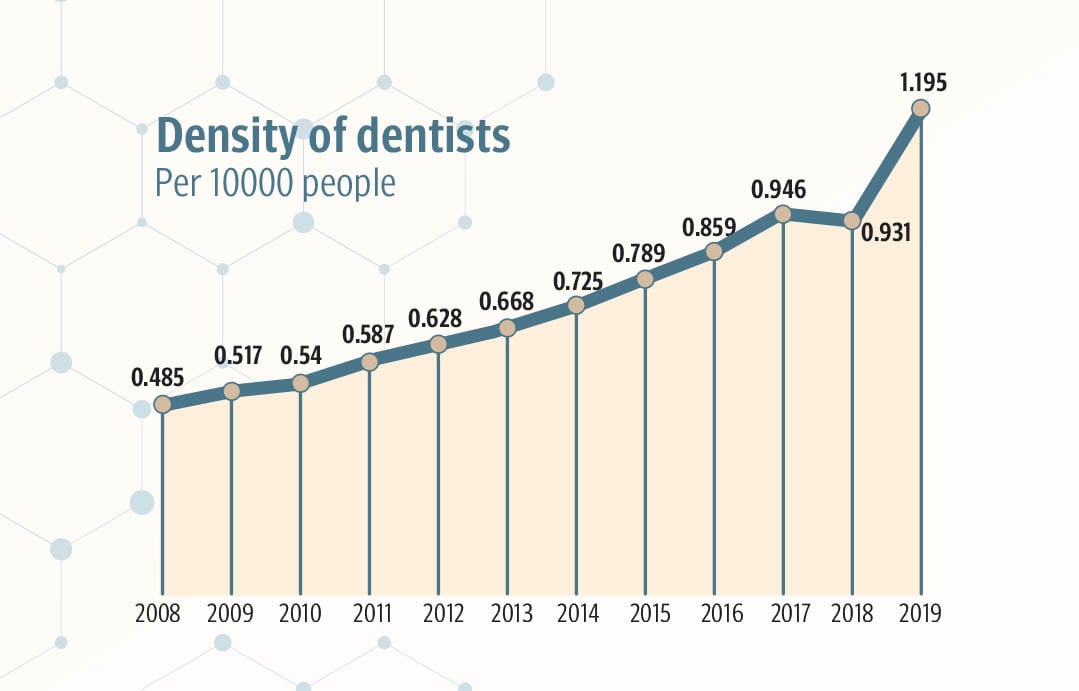

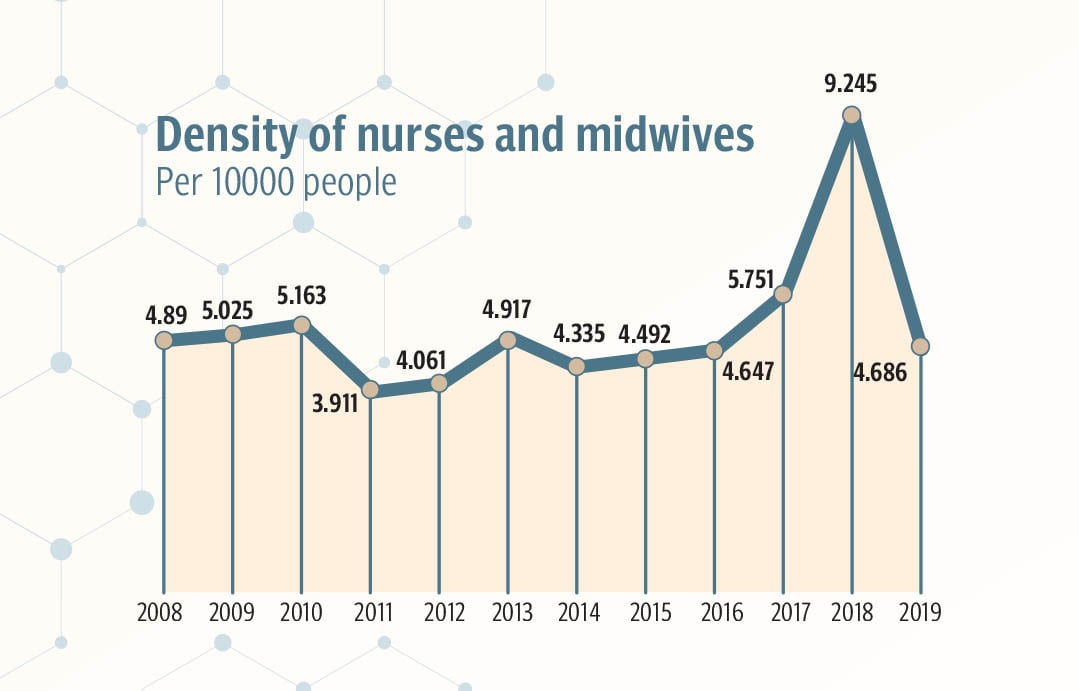

In terms of infrastructure, the country has a total of 1,233 hospitals, including 721 public and 512 private hospitals making only 1.2 hospital beds per 1,000 people, compared to the global average of 2.9 hospital beds per 1,000 people. According to World Health Organisation, the country also has a severe shortage of healthcare professionals, with only 0.8 doctors per 1,000 people, compared to the global average of 1.5 doctors per 1,000 people, and 0.4 nurse per 1,000 people.

The statistics only tell part of the story. Behind every number, there is a person, a family, a community struggling to access quality healthcare. Take the story of Farhat*, a 45-year-old woman who works at a garment factory in Karachi.

Farhat's husband, a former electrician, has been suffering from a debilitating lung disease that has left him unable to work. Despite her best efforts, Farhat has been unable to get her husband the treatment he needs.

"I was a whole housewife back then, and my husband fainted at his work," Farhat recalls. "I received a call that my husband fainted, and they're taking him to the public hospital in Karachi. I urgently went there and saw my husband lying on the stretcher without being treated. They wanted someone to take responsibility first and then start the treatment."

Farhat took responsibility for her husband's treatment and began the paperwork. However, even at the public hospital, she had to purchase some medication from outside. "Despite being a public hospital, I had to get some things from the pharmacy outside the hospital," she says. "I didn't have much money, so I had to borrow from my relatives."

After four hours of waiting, the doctors finally diagnosed Farhat's husband with a lung disease. However, the treatment was not straightforward. "They told me that the lungs of my husband are no more functioning, and they had to be treated," Farhat explains. "They said they have to put him on a ventilator and then give him medications to get his lungs functioning a little."

Farhat's husband was admitted to the hospital for a four before being discharged due to the unavailability of the beds and that there were more severe patients than her husband. However, the treatment was not complete, and Farhat was left to care for her husband on her own.

"They gave me some instruments and medications, but they were not enough," she says. "They were only for three days, after that, I had to buy them from the pharmacy, which cost me around PKR 10,000 per month. It was not possible for me to bear."

With no other option, Farhat was forced to find work to support her family. She took a job at a garment factory, working 12 hours a day to earn a meager salary. "I worked there for 12 hours, and when I came back home, I didn't have much energy left to look after my husband," she says. "But I had to, as the hospitals were full, and they didn't have space to treat my husband."

Farhat's children, a 21-year-old daughter and a 19-year-old son, also work at the factory to support the family. "I realised that I was earning only PKR 20,000 per month, which was not enough to run my family," Farhat explains. "So, I had to put my daughter and son in the same factory so we can earn enough to take care of my husband and run things at my home."

Farhat's story is a voice of millions of Pakistanis who are unable to access quality healthcare. Despite her best efforts, she has been unable to get her husband the treatment he needs, and her family has been forced to sacrifice their well-being to make ends meet. "I feel like I'm losing him," she says, her voice cracking with emotion. "I just want him to get better, but I don't know how to make that happen."

"If the government facilities were good enough, and they had treated him fully before discharging him, I wouldn't have to face this much struggle in my life," says Farhat.

The human cost of Pakistan's healthcare crisis is devastating. Families are torn apart by illness and death, communities are ravaged by disease, and individuals are left to suffer in silence. It is a cost that is being borne by millions of Pakistanis every day, and one that can no longer be ignored.

Government initiatives

The government of Pakistan has taken steps to address the country's healthcare challenges. One notable initiative is the Universal Health Coverage Act 2024, which aims to provide health insurance to all citizens. Although details of the act are scarce, it is expected to increase access to healthcare, particularly for low-income families. The government's vision for universal health coverage is ambitious, and if successful, it could significantly improve healthcare outcomes for millions of Pakistanis.

To achieve this goal, the government has launched several healthcare programs. Mobile health clinics, for example, provide basic healthcare services to rural and underserved areas. Staffed by trained healthcare professionals, these clinics offer services such as vaccinations, check-ups, and referrals to specialised care. Immunisation initiatives are another key area of focus, with the government launching several programs to combat vaccine-preventable diseases. The Lady Health Worker Programme is another notable initiative, employing over 90,000 community health workers who provide basic health services to marginalised communities.

Another notable initiative of the Government of Pakistan is the Prime Minister's National Health Program, which provides health insurance to low-income families, aiming to increase access to healthcare for the most vulnerable populations.

Another crucial program is the Sehat Sahulat Program (SSP), launched in 2015 by the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa provincial government and later expanded to other provinces by the federal government in 2019. The SSP provides free healthcare services to poor families, with the goal of protecting citizens from financial hardship due to unexpected medical expenses. The program offers health insurance cards to eligible families, allowing them to receive healthcare services at partnered hospitals and clinics, with coverage of up to one million rupees annually.

The SSP has made significant progress, covering over 44.6 million households across 36 districts in Punjab, 35 districts in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and other provinces. The program has also helped reduce financial hardship for marginalised populations, including disabled individuals and transgender individuals registered with the National Database Regulatory Authority (NADRA).

These programs demonstrate the government's commitment to strengthening primary healthcare and health financing reforms. By prioritising universal health coverage, primary healthcare strengthening, and health financing reforms, the government aims to create a more equitable and effective healthcare system. The success of these programs will depend on sustained funding, effective implementation, and a commitment to addressing the systemic challenges that have long plagued Pakistan's healthcare system.

Plugging the gaps pro bono

Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) play a vital role in Pakistan's healthcare system, filling gaps in services and providing critical support to marginalised communities. While some NGOs operate on a large scale, others work at the local level, making a significant impact in their respective areas.

Some notable NGOs in Pakistan's healthcare system include, Edhi Foundation, which was Founded by Abdul Sattar Edhi, provides a range of services including emergency medical care, orphanages, and food banks. The foundation has, rescued over 20,000 abandoned children, provided shelter to over 50,000 orphans, offered free medical care to over 1 million patients.

Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital founded by Imran Khan, is another state-of-the-art cancer hospital that provides free treatment to thousands of patients every year. The hospital has, treated over 200,000 cancer patients, provided free treatment to over 75 per cent of its patients, achieved a survival rate of over 80 per cent for certain types of cancer.

Other notable NGOs include; LRBT (Layton Rahmatulla Benevolent Trust), providing free eye care services to the poor, treated over 50 million patients, Indus Hospital, a free hospital in Karachi that provides quality medical care to the poor, and has treated over 1 million patients, then there is SIUT (Sindh Institute of Urology and Transplantation), a renowned NGO that provides free medical care to patients with urological and nephrological disorders. Founded by Dr. Adibul Hasan Rizvi in 1975, SIUT has treated over 1.5 million patients, established a state-of-the-art hospital with modern facilities and equipment, and trained thousands of healthcare professionals in urology and nephrology.

While these large NGOs are making a significant impact, other NGOs like the Latif Kapadia Memorial Welfare Trust (LKMWT) are also working tirelessly to provide better healthcare to local communities. Founded in 2007, LKMWT is a non-profit organisation that aims to provide quality healthcare services to the underprivileged. The trust operates a hospital in Karachi, which provides a range of services including emergency care, surgery, and diagnostic testing.

Over the years, LKMWT has treated over 1.5 million patients, with a monthly average of over 2,500 patients. In 2022, LKMWT expanded its operations to Surjani Town, increasing its reach and impact in Karachi. More recently, in 2024, LKMWT launched its "Wellness for All" campaign, offering free medical check-ups and promoting health awareness among marginalised communities.

In addition to its clinical services, LKMWT has also organised several health awareness campaigns, focusing on critical areas such as maternal health, vaccination, and diabetes. The trust has conducted workshops and seminars to educate women about prenatal care, childbirth, and postnatal health. It has also collaborated with government agencies and international organisations to promote vaccination drives and prevent the spread of infectious diseases.

Furthermore, LKMWT has launched awareness campaigns to educate people about diabetes prevention, management, and treatment options. These initiatives have been supported by key participants and notable guests, including healthcare professionals, government officials, and community leaders.

For Ahmed Kapadia, Founder and Chairman of LKMWT, the trust's work is a labor of love. "I am proud to have bought my father's dream to life," he says. "Latif Kapadia was a man who cared deeply about the welfare of others, and I am honored to be carrying on his legacy through LKMWT. Our mission is to provide quality healthcare services to those who need it most, and we will continue to work tirelessly to achieve this goal."

The journey to improve Pakistan's healthcare system is ongoing, with both the government and NGOs working tirelessly to address the challenges. While significant progress has been made, there is still much work to be done.

To further healthcare in Pakistan, it is essential to prioritise sustainable funding, strengthen primary healthcare, and promote health-financing reforms. By doing so, Pakistan can create a more equitable and effective healthcare system, where quality medical care is accessible to all, regardless of income or social status.

Ultimately, the future of healthcare in Pakistan depends on the collective efforts of the government, NGOs, and individuals to ensure that every citizen has access to quality healthcare, dignity, and a chance to thrive.

*The names in this story have been changed at the request of the individuals featured