Once upon time, there was a place called FATA, at times called the most dangerous place on earth. It was the picture of ultimate disparity compared to rest of Pakistan, backwards in regard to every conceivable human wellness indicator. Then, in 2018, it was merged into the national mainstream in Pakistan, and re-branded as newly merged districts (NMDs). The draconian law of Frontier Crimes Regulations (FCR) was repealed, and FATA got the laws and policies of Pakistan- people got the same constitutional protections as every other citizen.

And then, all was well.

Or, was it?

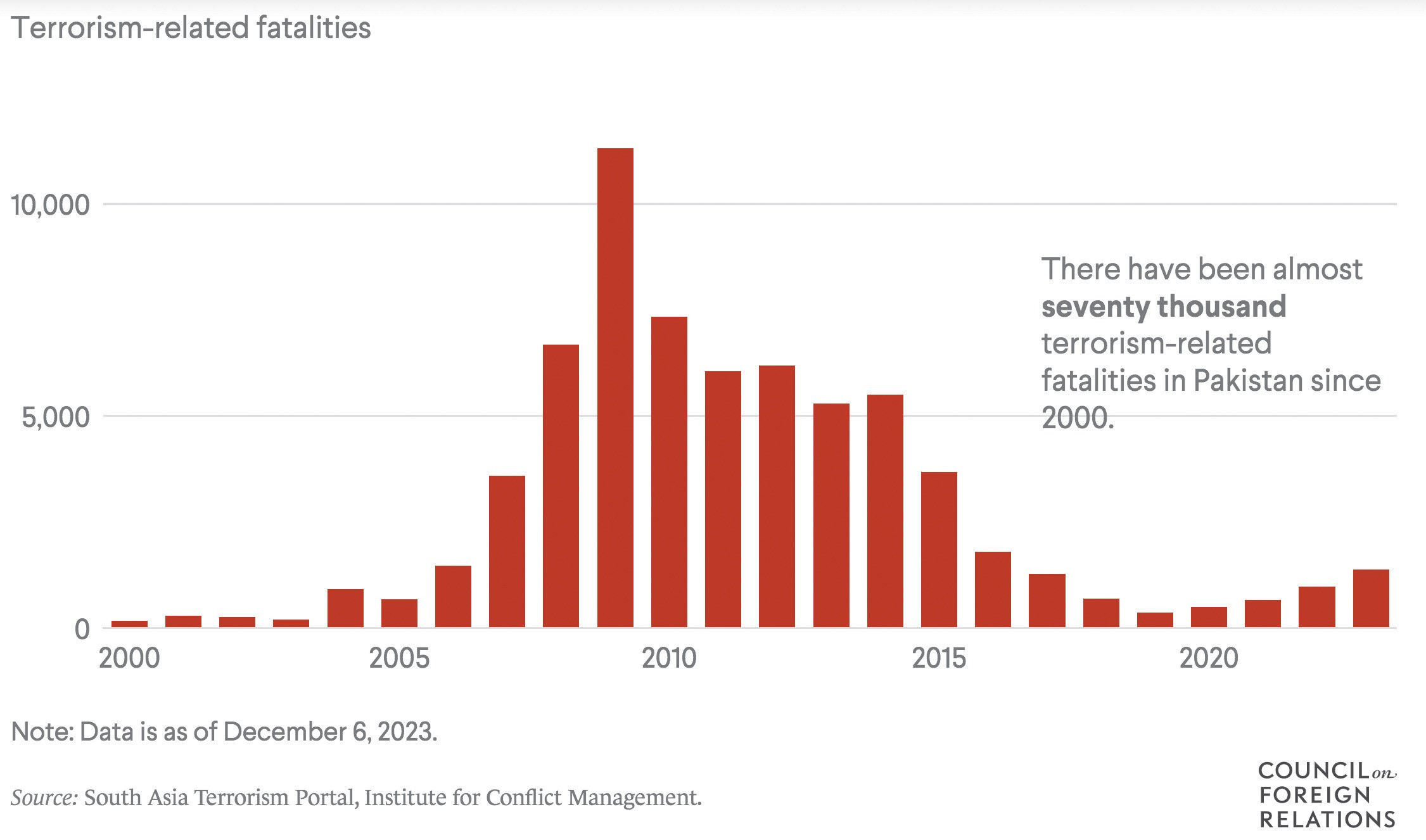

The recent killings in Kurram and continuing instability from terrorism highlight the insecurity in these newly formed districts. This is symptomatic as well of a deeper, underlying problem that plagued FATA and continues to plague NMDs: weak governance frameworks. Glaringly among this governance deficit, a nascent police stands out.

NMDs did not just get rights; they also got a police force, theoretically. However, just as an apple by any other name is still an apple, and just as NMDs are still FATA in their outlook, so is their police force: a rag-tag conglomeration of tribes, headed by more experienced police officers. Re-designating geographical boundaries has not changed tribal outlook. The worldview and the long-standing problems of FATA have just been handed down to the NMDs and its police force.

The context

The context

Before the merger of former FATA into the K-P province and the creation of regular districts out of the former frontier regions and tribal agencies, the area was being administered under the Frontier Crimes Regulation (FCR). Under FCR, collective responsibility and collective punishment for crimes committed by individuals were the norm, as per the tribal traditions. There was no separation of executive from judiciary. Every individual was treated as an integral part of a tribal community, and his actions would also affect his tribe.

Jirga was (and still largely is) the form of dispensing justice. There was no formal investigation, prosecution and trial as we associate with the modern-day criminal justice system. Coercive force was rarely used to arrest suspects; under the spirit of tribal responsibility, tribes were expected to bring the offenders before the Jirga.

Justice provision in NMDs is thus attuned to dispute resolution because of the long-standing tradition of Jirga. Foreseeably, this propensity for dispute resolution will remain for some time, as it gradually, painfully, transitions into a more individualised rule of law. However, old habits die-hard in the tribal areas; habits become tradition, and tradition is sacrosanct. Thus, when the police opt to make arrests, because of lack of knowledge or legal skills or the system of the area, they usually come back after partaking in a Jirga. This is because the system of the tribal areas has always been based on collective responsibility, rather than on responsibility for individual offences committed by someone.

Entities maintaining law and order in these areas were divided into the Levies, the semi-formal police organisation under the political agent, and the Khasadars, the honorary police officers, serving on behalf of their tribes. Their nomenclature and rank-structures were inspired by military organisation. For Khasadars, there was no standard of recruitment except their tribal origin, and they were more numerous than the Levies. Both Levies and Khasadars have been now integrated into the Police force. A judicial system has also been notified, replacing FCR, ostensibly, with Pakistan’s criminal justice system; this is easier said than done.

Supposedly, under the Constitution, individual criminal liability, investigation and prosecution as provided under the Criminal Procedure Code, and punishments as provided in the Pakistan Penal Code, are now applicable to NMDs. Application of Police Rules and Police Efficiency and Discipline Rules also apply. However, enforcing these laws and rules even in Pakistan’s settled cities and districts has been a major challenge for policing, despite the Police forces in Pakistan having decades of experiential learning.

How will the almost illiterate and untrained new police force in NMDs fare? Can they even be trained, even though K-P police has been directing one training after another, at them?

NMDs have a force of 25,000 officers comprising the Levies (that had some formal training), and the Khasadars. Both lacked proper regimentation and discipline as we associate with regular police. Under the FCR, Levies and Khasadars, now suddenly becoming Police officers almost overnight, had very limited roles and duties. Since there was no formal criminal justice system based on modern concepts of investigation, prosecution and trial. Jirga was the means of dispensing justice. There was no separation as such of executive and judiciary, either.

There were no strict recruitment criteria, training regime or career planning or career progression rules. Award of ranks was also arbitrary. The Khasadars particularly were an honorary rank, and a large number of them were not physically present in the country, but were still enrolled and drawing salaries. They provided their ‘replacements’, or ‘Iwzis’ to work when needed. The nature and scope of duties allotted to them was also very limited, unlike the modern civilian law-enforcement. They were doing either the ‘Phatak’ or barrier/check-point duty to stop and search vehicles, or the ‘Badarga’ duty, which means security, escort, or arrest duty. However, now the police are supposed to do much more.

As we all know, security is the most basic issue in NMDs, but the capacity of NMD police officers is debatable in enforcing rule of law in these highly troubled areas. Police still cannot operate without the active involvement of military. The security situation in Pakistan's newly merged districts remains highly volatile, marked by frequent terrorist attacks and instability. Despite efforts, the police face severe capacity challenges, including limited resources and training, hampering their ability to effectively control the situation.

New policing duties and new public expectations are staring the former Levies and Khasadars in the face, and most of them are baffled by the change and disoriented in the face of new challenges. Policing in NMDs requires development of new attitudes, behaviours, policing practices, codes of conduct, discipline and accountability if the police officers are going to step up to the challenge of deteriorating security problems.

How will that happen?

Well, it won’t, at least not until the foundational issues of the rag-tag police force in NMDs are solved.

Administrative challenges

Administrative challenges

At the time of merger, there was resistance from both the Levis and Khasadars. In order to deal with this challenge, the government and the senior police leadership offered them terms; these concessions have become a stumbling block for their development as a professional force. As appeasement, 22 points of concessions were granted. One of the most important promises made was that they would not be displaced from their present districts, and they would not be posted to the former settled districts. Similarly, they were also promised that officers from the settled districts would not be posted in the NMDs, to replace the command structure.

These terms discourage re-location and adjustment of police forces to new environments, which is a time-tested method of managing transition successfully. Transfers and postings, managed judiciously, encourage learning and adaptive behaviour; this has been stifled in NMDs. After the merger, all the laws, rules and procedures of the criminal justice in vogue in other parts of the country are ostensibly applicable to NMDs.

However, the NMDs are not like the rest of the country, and have never been. They have been a distinct closed society within the larger Pakistani society, and expecting that they would become ‘modernised’ instantly after passing some laws was, putting it mildly, a simplistic assumption. Erstwhile FATA was a place of staunch tradition and tribal pride, and renaming it as NMDs has not changed any of that. It might have been prudent to make haste slowly, but the merger was effectively ‘pushed through’ in haste.

That does not mean in any way that the merger was ill advised; it was a sorely felt need of the hour to bring these areas into the national mainstream. However, as with many things, it was the way that it was pushed through, without strategic far sightedness, which is the issue.

Regulatory quality is not exactly the speciality of Pakistan’s civil bureaucracy. The weakening governance indicators across the board are testament to that. Ingenuity is also in short supply.

The new police force could not have been just re-constituted from their old structures, but it was. Some transition time should have been allocated, but it wasn’t.

In order to fully implement the new system, formal police training, discipline and accountability are a must, requiring significant behavioural change, knowledge expansion and skill development. Without discipline, there can be no accountability of the police force. The former Levies and Khasadars have been assigned police ranks, but their conversion has not transformed them. They have been imparted some basic training in physical drill, wearing of uniform, and police operations, but still they have a long way to go. Their service-structure, and their promotions are a big challenge.

Many Khasadars are enjoying the ranks of a DSP because of their higher status in the tribe, while others, recruited at the same time, are just constables. It is thus not uncommon to witness an illiterate DSP supervising his more educated junior subordinates. This is unsustainable; in the past, their promotions have been granted without any promotion rules. Now, they are supposed to qualify all the courses required for promotion, and a large number of them being illiterate, will not qualify for these promotion courses. Will they be just ‘pulled through,’ or will they remain DSPs till they retire? Both options are not tenable in any smoothly functioning police force. More importantly, how will they get capable future leadership?

Change management is a big challenge in the MDs. The officers have still not fully accepted this merger and some of them hope that this whole process may someday be reversed. The region has more than 100 years of history when a different system was implemented. The force in the MDs is baffled, disoriented and unable to know what is expected of them, and how they can do it.

There is a unique phenomenon in these regions: police unionism. The officers sometimes take out processions and protests in order to register their grievances. For instance, in the not so distant past, police in North Waziristan tribal district threatened to indefinitely stop performing their duties, unless the provincial government annulled its decision of delegating magisterial powers to deputy commissioners in the region. North Waziristan police also called a Jirga in Peshawar to address this issue. Similar incidents have cropped up in other NMDs, which belies the considerably loosely held fabric of this nascent police force.

Operational challenges

Operational challenges

The lack of resources manifests in both human and equipment. Response to and registration of crime, HR management, documentation, criminal intelligence gathering, investigation, collection and preservation of evidence, chain of custody and preparing challans for prosecution and trial are still practices new to most NMD Policemen. There is no concept of community and public outreach, and public-police interface is extremely limited.

A small number of upper subordinates (sub-inspectors mainly) have been transferred from the settled districts/areas to the NMDs to take up investigation of crime in a professional manner. They are also mentoring the willing members of police in NMDs. However, there is stiff resistance by the locals in regards to what they perceive as ‘forced imposition’ of ‘non-locals’ upon them.

Inadequate policing skills, poor knowledge of laws and rules, lack of understanding of the concept of public service and individual rights and responsibilities, lack of supervisory skills, lack of operational planning skills, all impede successful police operations. In many merged districts, DSPs are simply incapable of performing duties as supervisory officers/sub-divisional police officers; they are not trained and carry no professional superiority vis-à-vis their subordinates. They still tend to act like a loosely connected community of men who can bear arms, and can perform some basic security functions. Investigation of crimes is a major challenge.

Police operations and investigation are concepts alien to the force in these regions. They are gradually learning new things, but the pace is slow and needs proactive intervention by the senior officers. Investigation is a core policing function on which the criminal justice system rests. Police officers in the NMDs are not trained in the collection, preservation, custody and production of evidence.

They are also not trained to be prosecution witnesses at a trial. Hence, core policing functions are in a rudimentary form. The limited use of IT for delivery of policing services is another challenge, which needs addressing. The operational capacity of specialised units such as various rapid response forces and the CTD is also limited, and needs enhancement on an urgent basis.

There is a serious need for empathetic leadership that ensures inclusivity in decision-making. Senior officers may need to address genuine issues of the force on priority. All stakeholders must support the police command and give them the full authority to take the MDs’ force forward. This requires constant logistical, financial and political support.

The answer has been to post experienced police officers as District Police Officers (DPOs) in these areas, sometime from the Police Service of Pakistan (PSP). However, even if the DPO was the most dedicated and experienced police officer serving in Pakistan today, he would still face almost insurmountable obstacles.

NMDs have tended to be funded by umbrella grants (read ‘makeshift arrangements’) as opposed to the Public Sector Development Programme (PSDP) in Pakistan (regular budgets for infrastructure development). Thus, adequate funds are almost never available.

On the other hand, NMDs probably have the highest number of weapons per household, as opposed to anywhere else in Pakistan. The police are outgunned almost in every district even by the tribes they are supposed to protect, and at times, arrest. This can be easily observed in Kurram and elsewhere in NMDs, whereby the only tenable option for the district administration is to negotiate for peace with the tribes, whenever there is unrest. ‘Lashkarkashi’ or tribal mobilisation has tended to occur, sometimes on a massive scale as was observed in Kurram recently, but arrests for what is essentially violating the writ of the state are, at best, lacklustre; that is an understatement of the highest order. Couple this with terrorism and extremism, which is fuelling continuing instability in these areas, and you, have the worst place in Pakistan for a police officer to serve effectively.

Thus, any DPO posted-in would immediately need to tackle rising terrorism and insecurity in the region, for which he requires an effective, trained, police force. All he gets is a lop-sided response from his juniors, and more often than not, gets so mired in administrative issues that he rarely has chance to address foundational problems of his police force. Most of his time is spent meeting ‘Musheeran’ (local influential maliks amenable to the state) to sort one problem or another, or having meetings with military to bolster his weak police force.

As hinted earlier, the police force in NMDs is facing serious infrastructure and logistical challenges as well. There are no proper police lines, no proper DPO offices, no properly secured police stations and police posts. The region is still volatile and blistering with terrorism. For police to be able to respond in some way to the existing security threat, it is imperative to build their Elite force, their CT capacity, traffic management services, for which investment in infrastructure, security equipment, arms and ammunition, and CT weaponry is a must.

Good service delivery is fairly contingent on the enabling environments and operational and logistical capacity. You simply cannot put an end to absenteeism if there is no place to stay for a police officer. Police barracks, lines, stations are a basic need.

Similarly, good quality vehicles are necessary for the kind of terrain these regions have. Bulletproof vehicles for each district and sub-division are also necessary. DPO offices have been set up wherever some space was available, but need massive improvement. These are not purpose-built buildings or complexes. Security of premises is still a big challenge, as police officers are a soft target for terrorists in the area. Because of poor infrastructure and inadequate logistics, officers are generally reluctant to serve as DPOs in NMDs.

Policing is an expensive enterprise, but funding quality policing services is important to effective law-enforcement. Hence, a realistic assessment of police logistical needs is important. The areas are large, mountainous, and there is no effective communication system for police operations. Police has to often rely on the communication system of the armed forces in case of emergency. They are also dependent on the army for security in many areas because of the threat of terrorism.

Priority areas

Priority areas

The capacity needs of the operational field officers within both police and district administration are different from their supervisory and command tiers. Operational tiers of Police are dealing directly with the public in distress looking for redress of grievances, as victims of crime, or as citizens in need of a driving license or a character certificate. People also come into contact with police while passing through police checkpoints, while driving, engaging in a protest, or sometimes as suspects.

Therefore, in addition to enhancing service delivery skills, police essentially have to handle conflicts that are germane to everyday policing. Every administrator and police officer finds himself among parties fighting over claims and counter-claims. Conflict resolution is an essential skill for field officers at all levels, but especially at the level of upper-subordinates (ASI to Inspector). At the same time, since this essentially never happened, police in NMDs need to be attuned to the issues of public dealing and conflict management.

Is the implementation of these suggestions even possible? Imparting knowledge and training to illiterate officers, some of who are DSPs, is no small task, is it?

Probably not—so what is the way forward? We cannot simply set them aside, as that would ruffle too many feathers, which is not tenable in the current environment of the NMDs.

Well, one approach might be to gradually and subtly redirect these officers to purely tactical units. Modern policing skills require field craft, which in turn necessitates literacy, which is in short, supply in NMDs. Thus a viable strategy would be to assign less literate officers to roles like handling weapons, conducting raids, and supervising field operations. At the same time, robust recruitment drives would promote intake of more educated police officers. In time, the literacy levels of police in NMDs would skew in the favour of educated young men and women.

The DPOs need to share a common vision, purpose, and intention to hire subordinates, instead of just reacting to stimuli. NMDs will continue to be in flux for the short to medium term at least, but that should not stop DPOs from initiating organisational change programs, some of which might not see fruition long after many DPOs have been posted out.

The organisational culture of police in NMDs might evolve to be slightly different from other police forces, but that is absolutely acceptable—police leadership needs to be flexible, creative, and adaptive in implementing change. Thus, when a certain specific outcome is pushed (i.e., the police force must operate in a particular way in NMDs) as the only possibility, progress is hampered. Police leadership might need to understand that there might be nuances to policing in the NMDs, unique from elsewhere in the country. Alternate dispute resolution and mediation as added police functions immediately come to mind, given the tribal structure and mindset of the society, found no where else in Pakistan to the same extent.

The Police Service of Pakistan must understand and accept the fact that most change takes time and may not even happen within the careers of the PSP officers trying to implement change. They should simply do their part in moving ideas further toward acceptance and implementation. Similarly, all involved need to accept that they will possibly not receive any credit for their efforts. This flies in the face of the immediate impulse of police leadership in Pakistan, who tend to make decisions with a view to immediate outcomes.

Thus, the diversion of resources, as mentioned above, needs to be tackled with utmost sensitivity to tribal traditions and the legacy of the Khasadars and Levies before they were merged into the police.

However, police unionism cannot be allowed to impede progress. These can be sensibly replaced with grievance committees or something similar set up by police leadership. Police managers must create an organisational culture that communicates direction and mission before expecting officers to embrace these changes; change will not come overnight. In any case, reorganising the police force in the NMDs requires much deeper and more strategic thinking.