Concern over mental health is on the rise in Pakistan, a nation of more than 230 million people, where significant issues persist due to cultural stigma, lack of awareness and poor facilities. The nation's health system finds it difficult to offer proper care even though mental health problems impact people of various ages, socioeconomic backgrounds, and geographic locations.

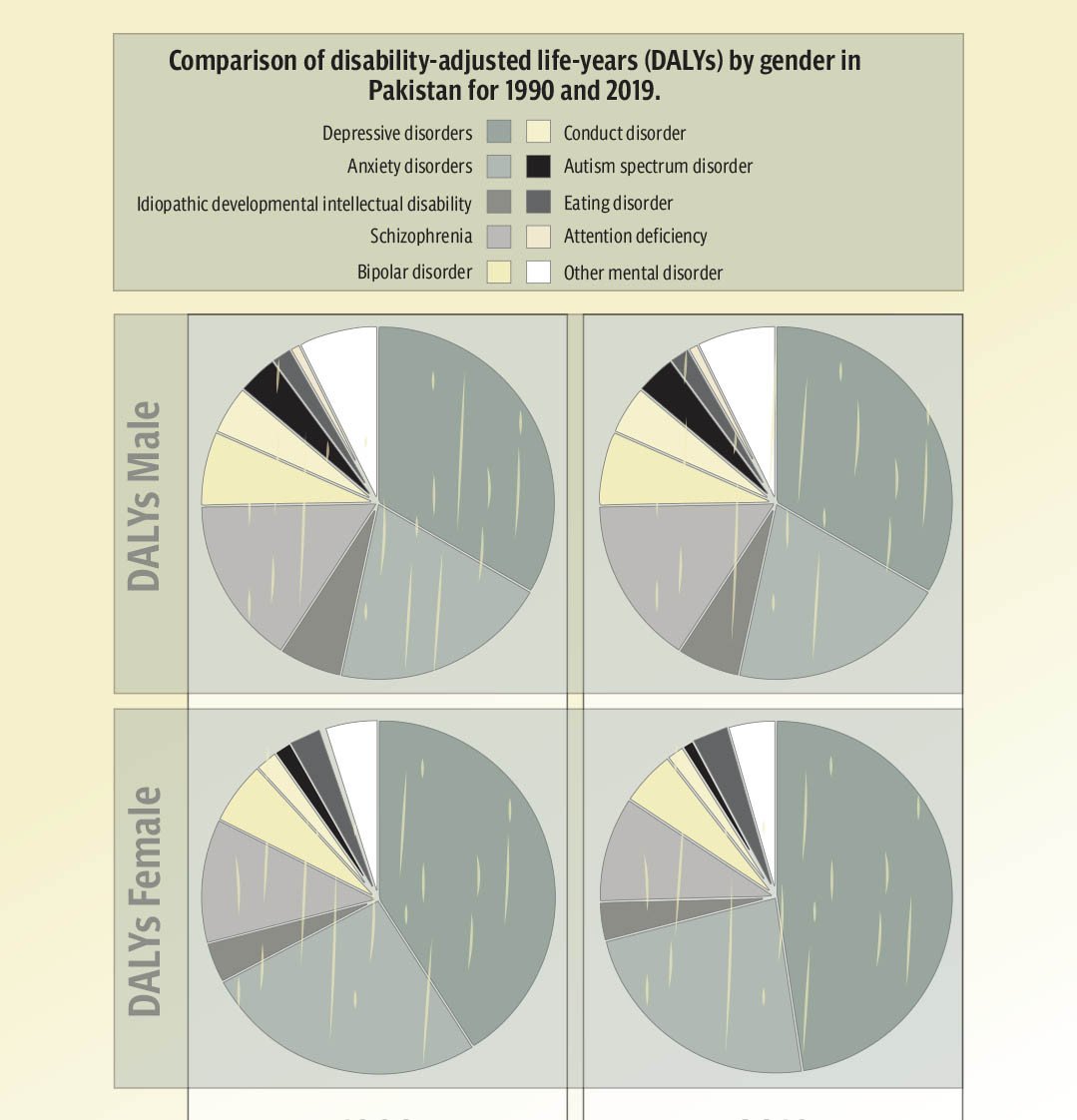

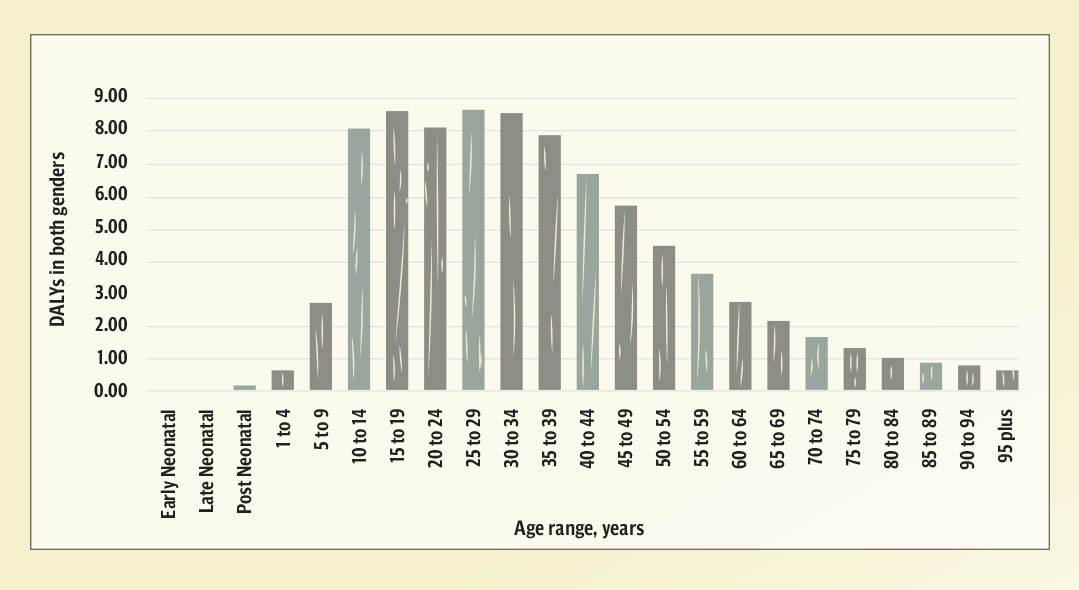

Mental health illnesses are increasing in Pakistan, impacting between 10 to 16 per cent of the population. According to estimates from the World Health Organisation (WHO), 25 per cent of Pakistanis may suffer from a mental health illness at some point in their lives. Millions of people suffer from some of the most common conditions, including schizophrenia, anxiety, and depression. It is concerning that up to 34 per cent of young people report having symptoms of anxiety and depressive disorders, with sadness and anxiety being especially common among women and young people. These figures point to a mental health crisis that has to be addressed on a larger scale.

“I was 29 when I realised I was suffering from anxiety and childhood trauma. During my master’s programme, my university arranged counseling sessions. It has been almost five years that I have been visiting several psychologists and psychiatrists, and till today, no one in my family knows that I am undergoing therapy,” said 34-year-old Yamna Khan*. She also said that when any child shows symptoms of depression or anxiety, they are told that they are less religious and have no faith in Allah, while she prays five times a day and is also an avid reader of the Quran. “I once tried talking to my mother, and all she had to say was that mental health is a Western idea, and none of these problems exist in our culture,” she lamented.

Numerous studies have tried to measure the prevalence of mental health issues in Pakistan and have found alarming patterns. Data to be believed from a private hospital found that between 15 and 35 per cent of people have mental health problems. For example, approximately four per cent of Pakistanis suffer from anxiety disorders, while six per cent suffer from depression. Thirty per cent of healthcare workers, particularly physicians and nurses, report having mental health problems as a result of stress and burnout. These numbers were made worse by the COVID-19 pandemic, which brought with it higher stress, bereavement, and financial difficulties, all of which led to a notable increase in mental health conditions. “If you just search about mental health numbers on the internet, one can have an idea what the millennials are going through, but no one is ready to have this conversation,” Khan said, adding that even few of her friends believed that she should focus on her work and family then just thinking about her mental issues more.

Research indicates that approximately 15 per cent of women have symptoms of postpartum depression. According to estimates, rates of anxiety and depression are significantly greater in rural and underdeveloped urban regions where access to mental health treatments is restricted. Furthermore, an increasing amount of data shows that school-age children and adolescents are dealing with mental health problems at previously unheard-of levels, frequently as a result of social media exposure, bullying, and academic pressure. “Mental health and their understandings work like trends such as around 2018 we started hearing more and more about anxiety and depression, but nowadays the trend is about relationship problems such as everyone comes up with a word red flag in their conversations,” said a clinical psychologist Syeda Masooma Zehra.

Mental health issues are still taboo, and long-standing social stigmas prevent people from talking openly about them or asking for help. People often reject therapy or counseling because of traditional beliefs that link mental illness to moral weakness or a spiritual deficit. “I have been taking therapy for almost four years now, and my family isn’t aware of it, and I know the moment I tell them, it will be another battle for me to fight,” said Azam Ali, an IT professional said, sharing his misery he said that a few years back he has a complaint of feeling breathless that also was impacting his vision and he would find it difficult to sleep, with these complaints he approached a general physician who recommended him therapy, and that was when he realised that he had panic attacks. “Families may be reluctant to seek assistance for loved ones out of concern about social rejection and societal condemnation. Because of this, a lot of people with mental health issues endure silence, which frequently makes their symptoms worse,” Ali mentioned.

Mental health problems are also significantly influenced by economic difficulties. Pakistan’s high rates of poverty, unemployment, and inflation make its people more stressed, anxious, and depressed. “There are different classes to it, and the lowest is where one can’t afford, and they don’t even know how problematic their minds are, which eventually affects their children in later ages that is generational trauma for children, but the other case is where one understands the need of therapy but cannot afford,” said Zehra adding that such people can do many other things such as balancing their lives and creating healthy boundaries because even a psychologist can tell you what to do but implementing in life is one’s own decision.

Many households find it difficult to pay for essentials due to increased living expenses, which cause ongoing stress that negatively impacts mental health. Financial hardship and mental health problems are strongly correlated, with people in lower income categories reporting higher levels of psychological anguish. “Therapy is expensive, and there is no other way to say this, but there are other coping mechanisms that can help people who cannot afford such as when one feels pressurised or thinks he has an anxiety attack, he can divert it by just going out take a walk, but yes that too isn’t doable for many people given the situation of the city and law and order,” the psychologist explained.

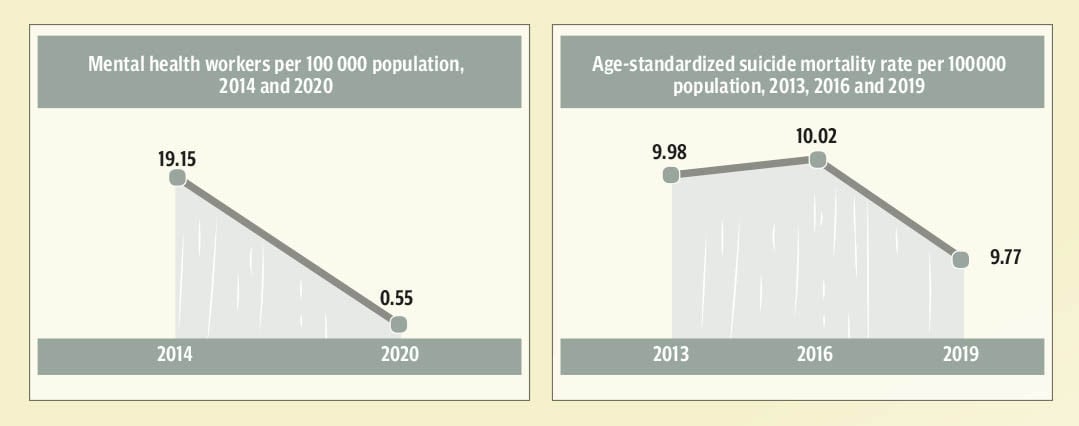

The facilities and resources needed to adequately address mental health needs are lacking in Pakistan’s healthcare system. There are very few psychiatrists in the country and even fewer psychologists and counselors, most of whom are based in large cities. A country that has a population of over 230 million lacks access to mental health care. Furthermore, there aren't many general hospitals that provide psychiatric care, and there aren't enough inpatient facilities for people with serious mental illnesses. “Other than big hospitals that charge a handful of amount, psychiatry services are not available everywhere. I started searching for better affordable options, and the lowest I could find was 2500 per session, and the experienced doctor was 9000 rupees,” said Khan.

Due to the widespread use of smartphones and internet connectivity, social media has taken center stage in the lives of many Pakistanis, especially the younger generation. Social media can lead to long-lasting effects on mental health even while it offers chances for expression and connection. According to studies, excessive social media use is associated with feelings of inadequacy, anxiety, and sadness, particularly when users contrast themselves with other people. “Having excess to information but the trends of influencing has gone far in real life, people try to compare their lives with others, even couples compare their marriage lives with celebrities which eventually ends in disappointment in reality,” the psychologist pointed out.

Mental health care is not vastly available across the country, especially in low-income and rural areas, compared to the rising demand for mental health care. Pakistan only allocates 0.4 per cent of its health budget to mental health, according to the WHO. Even if a few mental health institutions exist in large cities, they cannot serve everyone’s needs.

The public is unaware of where and how to get help, and community-based support like therapy or counseling is either completely unavailable or prohibitively expensive. “Someone who has to go through social stigma, taboo, and financial pressure to step up still has few options, which is alarming in itself,” Zehra explained, adding that there aren’t many mental health hospitals except in big cities, and people travel great distances or turn to traditional healers because many smaller cities and rural areas lack mental health facilities. “My uncle’s condition was never understood and was taken to some religious shrine in rural Sindh when after losing his job he went into chronic depression,” shared Iqra Ahmed, who is a psychology student, she also pointed out that most millennials, the education and exposure has made the difference but the generation before them have been under the influence of blind believes.

“People who are in need frequently go untreated, which can have serious consequences in some situations and worsen mental health like my uncle committed suicide after four years and no proper help,” she shared.

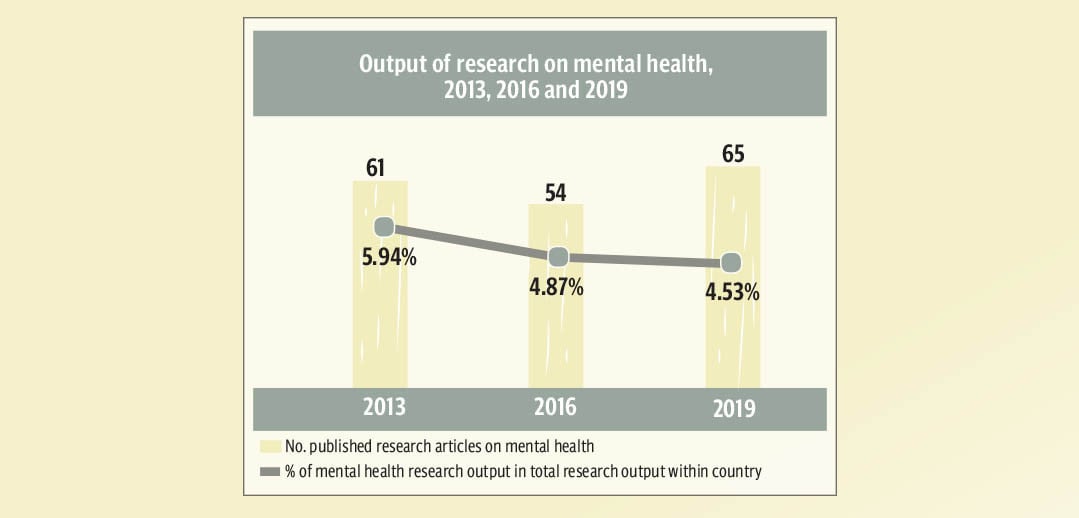

To address mental health issues in Pakistan, several projects have been started recently. Though these efforts are still in their early stages, the government has attempted to integrate mental health into a more comprehensive health policy. To raise awareness of mental health issues and enhance the standard of care in the province, the Sindh Mental Health Authority was founded. Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) also passed the Mental Health Act in 2019 to enhance mental health services and offer legal protections.

Additionally, non-governmental organisations are also addressing deficiencies in the healthcare system. Services provided by groups like the Aman Foundation and the Pakistan Association for Mental Health (PAMH) range from direct counseling and therapy services to mental health awareness initiatives. By offering online counseling and support services to people who might not otherwise have access to mental health resources, telehealth platforms are becoming more and more popular as an alternative. “The Initiatives such as telepathy can help more and more people speak up as they don’t have to face anyone or don’t have to get out of their houses, but that can only work if pursued seriously and not exploited like happens in most of the cases,” said the psychologist.

Destigmatising mental health concerns requires raising public knowledge. People can learn about mental health through campaigns in communities, companies, and schools that highlight the fact that mental illness is a medical issue rather than a personal shortcoming. “A more accepting and helpful perspective on mental health could also be promoted by media campaigns run by governmental and non-governmental organisations,” said Ahmed, who, with the help of her university and class fellows, arranges seminars and awareness campaigns about mental health.

Millions of people in Pakistan suffer from mental health problems, which have a significant negative social and economic impact on the country. Digital platforms and services can be used where in-person services are scarce; telemedicine provides a convenient and affordable means of providing mental health services. Particularly among tech-savvy young people and working professionals, the creation of telemedicine platforms and mental health applications may aid in closing the treatment gap. In Pakistan, online counseling services like Sehat Kahani are already available; growing these services could help a larger population. “Telemedicine is comparatively easier to take the first step in this direction and can help in building support groups and community-based mental health programmes that can offer people in emotional distress, but in some cases, even telemedicine isn’t enough,” Zehra said, adding that most people are told to talk to friends and rant but mostly friends cannot give good advice and wrong advice to an already depressed person can lead to severe consequences.