Imagine it's the winter of 1960 and you are having morning cup of tea in the small resthouse of Tangrot near the confluence of the River Jhelum and the Poonch. You arrived late in the evening and the local shikari is quickly assembling your reels to the 12-foot rods which are made of laminated bamboo strips and threading the nylon string through the eyes of the rod. Thought good for its time, bamboo rods did not have the flexibility or strength of carbon fiber you used ten years later. Quickly finishing your tea, you hurriedly head to the river, carrying your medium action rod with reel. The sun is already cresting the surrounding hills and you wish you had woken up an hour earlier. The Mahseer feeds from sunrise till 10 a.m. and is futile fishing until after 4 p.m. till sunset.

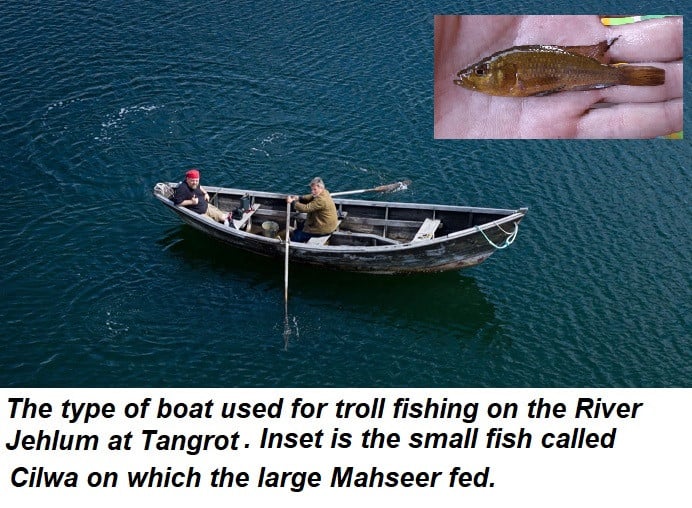

Behind you follows the shikari with another rod and reel, a landing net, and your box of tackle. The two of you clamber abroad the small riverboat you hired for the weekend and as the oarsman pulls it into the river he informs you, ‘Sahib. Ajj Chilwa bara nazar aya hai. Bari Mahseer mile gi.”. The Chilwa is a variety of small fish and the boatsman is informing you that they are on the run, so the fishing for Mahseer will be good.

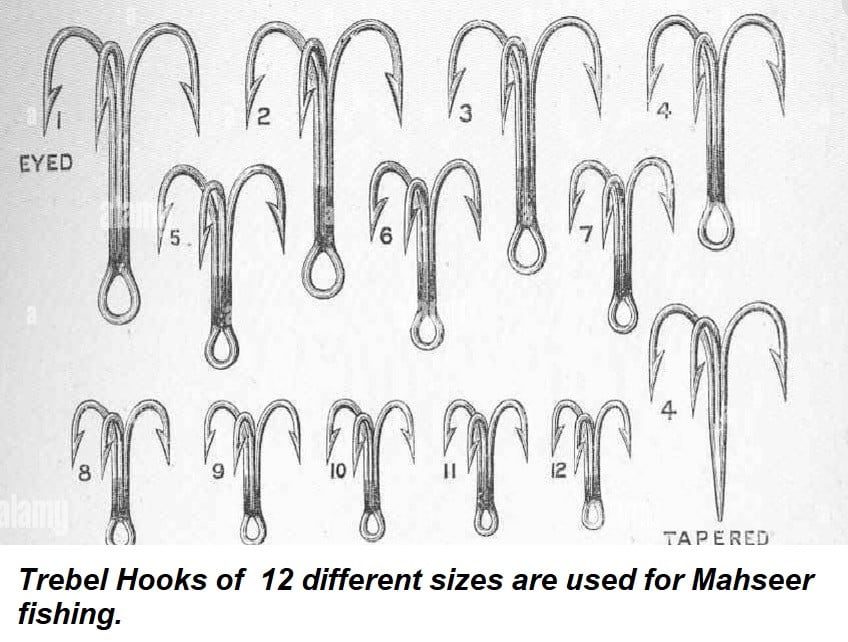

You seat yourself firmly on a plank at the rear of the boat and while the oarsman rows towards the large ‘pool’ formed by the confluence of the two rivers, you attach the artificial bait to the line – a 3-inch silver Devon spoon with a large treble hook. Your experience tells you that a single hook and enough lead weights to make it sink. As it is dragged against the current it swirls reflecting the light in flashes to catch the attention of the Mahseer. You let out 15 meters of line to allow the spinner to sink deeper into the waters where the larger Mahseer is feeding. Your nylon line has a breaking strength 20 kg; if you hook a fish larger than that, you must remember to bring it in very carefully. The boat ‘trolls’ upstream and while keeping a firm grip on your rod in case a fish bites, you take in the ruins of the Ranikot Fort perched on the other bank.

A jerk on the line pulls you out of the stupor induced by the rhythmic splash of the oars and you jerk the rod up to ensure that the treble hook is firmly embedded in the fish. To break free, the Mahseer leaps out of the water and falls back with a flash but in that instant, you can make out that it is no small size. You are overcome by a mix of fear and joy as you brace yourself for the famous rush of one of the best fighting fish in the subcontinent – nay the world. There is a high-pitched whine from the reel as the line unwinds from your Nottingham reel manufactured by Slater Brothers. You hope that the 15 kg drag set on the reel would ensure that the Mahseer would tire within 90 meters and you can start reeling it in till it rushes off again. It's going to be a long tiring battle.

Britishers in India and the Indian Royalty popularised fishing for the Mahseer and for some, it was akin to killing a tiger! It was for no small reason that it was called the ‘tiger fish’. In his famous shikar book, Maneaters of Kumaon, Jim Corbett writes, “Fishing for Mahseer in a well-stocked submontane river is, in my opinion, the most fascinating of all field sports.” Rudyard Kipling famously wrote about this stunningly beautiful legendary fish – “besides whom, the tarpon (a saltwater fish that is a challenge to catch) is but a herring”! In his classic work "The Rod in India," published in 1873, Henry Sullivan Thomas writes, "The Mahseer is to the rivers of India what the salmon is to those of Europe, the monarch of the stream… It is a grand fish, giving the best of sport and demanding the best of tackle, and of all fish, I think it gives the finest sport for the rod." He devotes over 100 pages in his 300-page book to elaborating on the species of the Mahseer and, the tackle required to catch it, the time of the year, etc.

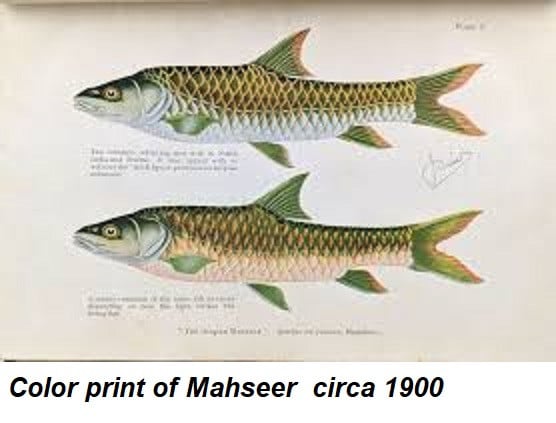

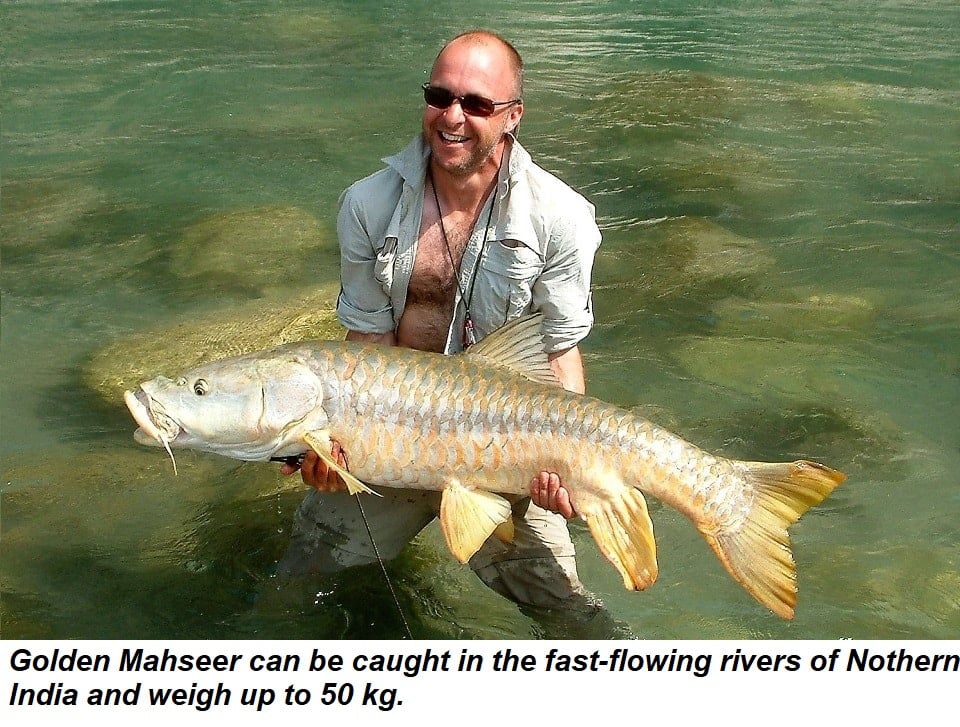

The Mahseer belongs to the carp family and is native to the subcontinent and Southeast Asia. Mahseer has a large, elongated robust body covered with thick scales, a single dorsal fin, and strong jaws with prominent lips. It has pharyngeal teeth set further back in the throat and used to grind food. Because of their strength, they have adapted to fast-flowing rivers. Their coloration can vary from golden to silver, often with darker hues along the back. The larger the river, the larger the Mahseer and in 1906, Murray-Aynsley a female angler caught a Mahseer weighing over 50 kg. In 1919 Lieutenant Colonel Rivett-Carnac made a catch of 60 kg which held the record in India until 1946. However, in the fast-flowing waters of the Himalayan Rivers, even a 7 kg Mahseer can put up a fight that is not for the faint-hearted.

One of the most vivid first-hand accounts of fishing for Mahseer in British India comes from Major A. St. J. MacDonald’s book "Circumventing the Mahseer and Other Sporting Fish in India and Burma" (1948). He describes fishing from the banks of the river in the mountains.

"The sun was just rising over the hills, casting long shadows across the river as I prepared my tackle. The river was broad and deep, with rapids some distance downstream. This was prime Mahseer country, where the fish could grow to enormous sizes, and the current made for a formidable battleground. I cast my line into a deep pool below the rapids, using a heavy spoon bait that I knew could withstand the force of a Mahseer’s strike. The water was clear, and I could see the glint of scales as smaller fish darted through the shadows. Suddenly, there was a sharp tug, and the line went taut. I struck hard, feeling the unmistakable power of a large Mahseer on the other end.

The reel screamed as the fish took off downstream, heading straight for the rapids. I knew this was the critical moment—if the Mahseer made it into the white water, the chances of landing it would be slim. I applied as much pressure as I dared, hoping to turn the fish before it reached the tumult. The rod bent double, and I could feel every powerful surge as the fish fought against the line. Inch by inch, I gained line, but the Mahseer wasn’t done yet. It made another dash for freedom, this time trying to dive under a submerged boulder. I could feel the line scraping against the rock, and my heart raced. I maneuvered along the bank, keeping the rod high, hoping to steer the fish away from danger.

After what felt like hours but was likely only minutes, the Mahseer began to tire. Slowly, I brought it closer to the shore, its silver-gold body gleaming in the morning light. With a final burst of energy, it made one last desperate run, but it was spent. I guided it into the shallows and waded in to bring it ashore. There it lay, a magnificent fish, nearly 40 pounds of pure muscle and determination. Its broad scales glistened, and its powerful tail still thrashed weakly in the shallow water. I knelt beside it, exhausted but triumphant. This was the moment every angler dreams of—a true battle with one of nature’s greatest fighters, the mighty Mahseer."

The Mahseer is a clearwater fish whose habitat in northern India ranges from 100 meters to 2000 meters. They flourish in riverine environments, from lower elevations in the foothills of the Himalayas to higher altitudes in the mountainous regions. Its strong and flexible skeleton helps it to navigate and resist strong currents and its bony structure provides greater stability and strength in turbulent waters. Though its flesh has a nice mild taste, the only way that it is edible is to boil the fish, remove the flesh, and make cutlets.

The rivers originating from the Himalayas, such as the Ganges (especially in its upper reaches), Yamuna, Sutlej, Beas, and their tributaries, offer excellent habitats for Mahseer. Himachal Pradesh, and Jammu & Kashmir provide opportunities for Mahseer fishing. So also, the rivers and streams in Uttarakhand, particularly those in the regions around Jim Corbett National Park, like the Ramganga River. One of Jim Corbett's most memorable experiences fishing for Mahseer is recounted in his book "Man-Eaters of Kumaon."

In the chapter titled "The Fish of My Dreams," Corbett describes an exhilarating and challenging encounter with a large mahseer in the Ramganga River, where he hooked what he called the "fish of his dreams"—a massive Mahseer. He spent hours battling the powerful fish, which repeatedly dashed for the safety of deep pools and rocky crevices. Corbett describes the struggle as a test of endurance, patience, and skill. Eventually, after a long and exhausting fight, Corbett managed to bring the Mahseer to the riverbank. He admired the fish, noting its size and beauty, before releasing it back into the water. It was a testament to his respect for nature and his evolving conservationist mindset.

Till the 1960s, Mahseer was found in the rivers of the NWFP like the Kurram, Kabul, the Panjkora and Swat. On the River Swat the best spots to fish were its confluence with the Kabul at Munda Headworks and at the resthouse on the banks of the river near the Chakdara Fort where the Mahseer mixed with the Snow Trout . Two famous locations in upper Punjab were Tangrot on the confluence of the River Jhelum and Poonch, and Tarbela where the River Siran met the mighty Indus. With the construction of two huge dams, both these sites are deep under water though there is fishing below their spillways.

My father was a very keen angler and in the late 1950s, he had formed an Anglers Association at Rawalpindi that had well-attended meetings in a room adjacent to the old GHQ Library. He never missed an opportunity to fish and while leaving for Lahore for an inspection, he also packed his fishing gear. The next evening my mother was sitting on the front lawn when a military jeep drove into the house and to her alarm two soldiers unloaded what looked like a body wrapped in tapeline. It was a Mahseer weighing nearly 40 kg that father had caught at Tangrot where he had stopped for a night. Driving back onto the GT Road the next afternoon, he saw a military jeep heading for Rawalpindi and transferred his load. On his return, he recounted how he had struggled for 3 hours to land the Mahseer.

As a young boy, I went with my parents to the two fishing spots on these large rivers. On one of our fishing excursions to Tarbela, we accompanied FM Ayub Khan, the C-in-C of the Pakistan Army. It was a large fishing party and the army had erected a line of tents along the river bank and established a mess. Amongst the group were two famous fishermen – Brigadier Sir Hissamuddin (HD) and Aziz Shikari. Both were Farsi-speaking Afghans and both were strong rivals.

One evening sitting at the dining table they insisted that the Mahseer they had caught that day was larger than the others and a bet was fixed. To keep the fish fresh, the catch-of-the-day had been tied and left floating in the river in front of the tent to whom it belonged. After the generator had been turned off and everyone had gone to sleep, Aziz Shikari crept down to the river pulled out his largest Mahseer, opened its mouth, and filled its stomach with small lead weights. He then put it back in the river and went off to sleep. A while later, Sir HD sent his orderly down to the river who exchanged the heaviest fish of Aziz Shikari’s catch with the smaller one of Sir HDs. The next morning after breakfast all the guests gathered to weigh the rival's largest fish and of course, Sir HD won. But Aziz Shikari had recognised the fish he had tempered with and accused Sir HD of cheating. Taking out his knife, Aziz slit open the stomach of his rival ‘winning’ catch and to everyone's astonishment including Sir HD, out fell the lead weights. Everyone was taken aback and then there was a roar of laughter in which Sir HD who was a good sport, also joined in. It took the others some time to solve the mystery of what had actually happened.

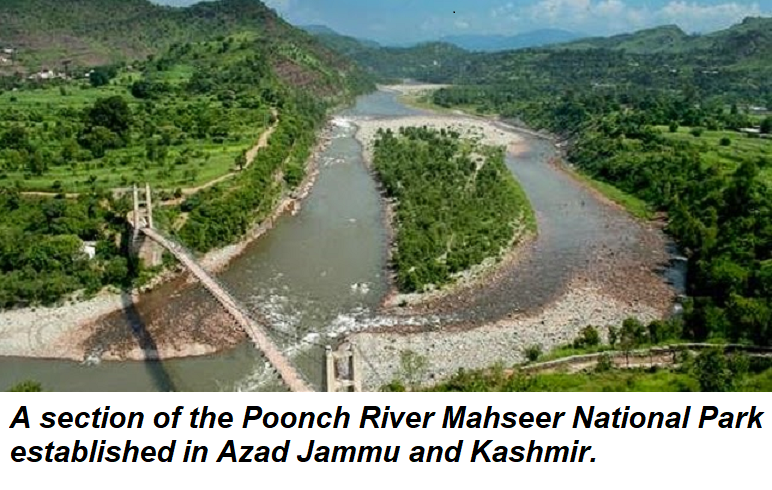

Sadly, the Mahseer has become nearly extinct in the rivers of Pakistan but one of the recent success stories of conserving it in its natural surroundings is on the River Poonch. With the success of the Himalayan Wildlife Foundation in saving the Brown Bear, Dr. Anis ur ReMn and Mr. Zakria teamed up with Dr. Rafique, an eminent expert on fish in Pakistan who encouraged the two to save the national fish of Pakistan. Fortunately, there remained a few pockets of Mahseer on the Poonch River where the water temperature and breeding grounds were conducive to the species' survival. It was an uphill task to convince the government of Azad Kashmir and the locals along a 100 km stretch of the river about the conservation of the species. However, they were lucky because a hydroelectric dam was to be constructed by a Korean company and the Himalayan Wildlife Foundation convinced the donor agencies that unless funds were set aside for the preservation of the Mahseer fish, it would become extinct. All this resulted in a habitat for the breeding of the Mahseer in the Poonch River National Park and the old residents living along the river confess that it is over 40 years since they have seen Mahseers weighing 30 kg.

Syed Ali Hamid is a retired Pakistan Army major general and a military historian. He can be contacted at syedali4955@gmail.com

All facts and information are the responsibility of the writer