It’s safe to say that Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif is in desperate search of a win. Struggling under a crisis of political credibility, a crisis of current and new economic constraints imposed by the IMF, and just recently, a bombshell report involving billions in payments to IPPs owned by him and his political allies, Sharif could use some positive news.

This week, he set out to do exactly that, proposing a shift in the country’s energy strategy, a shift that could potentially save the government upto 6 billion dollars in energy imports. While addressing the federal cabinet on 3rd August, he revealed a new policy to reduce dependency on imported coal to locally extracted Thar coal, a lignite coal extracted domestically. To do this, Sharif has written to Chinese authorities to reprofile loans linked to 3 major coal-fired power plants under the CPEC agreement, to help transition them from imported to Thar coal.

On paper, it sounds like a great idea. After all, the notion of utilizing the country’s natural resources to make it self-sufficient in energy generation has universal appeal. In fact, it may be the one issue that Imran Khan and Shehbaz Sharif both agree on. Former and current Finance Ministers, Commerce Ministers, and Energy Ministers were all on the bandwagon previously as well, arguing that a significant portion of the over 200 trillion rupees in capacity charges owed to Chinese plants for their loans, insurance and other investment costs have contributed to the high rates of electricity in Pakistan.

But before you all break out into applause, let’s take a step back. The devil, as always, is in the details. As much as we may love the idea of ‘khud mukhtari’ (freedom from dependency), we may be getting involved in a technical, financial and logistical quagmire that we may not realise.

How does foreign coal burden our energy sector?

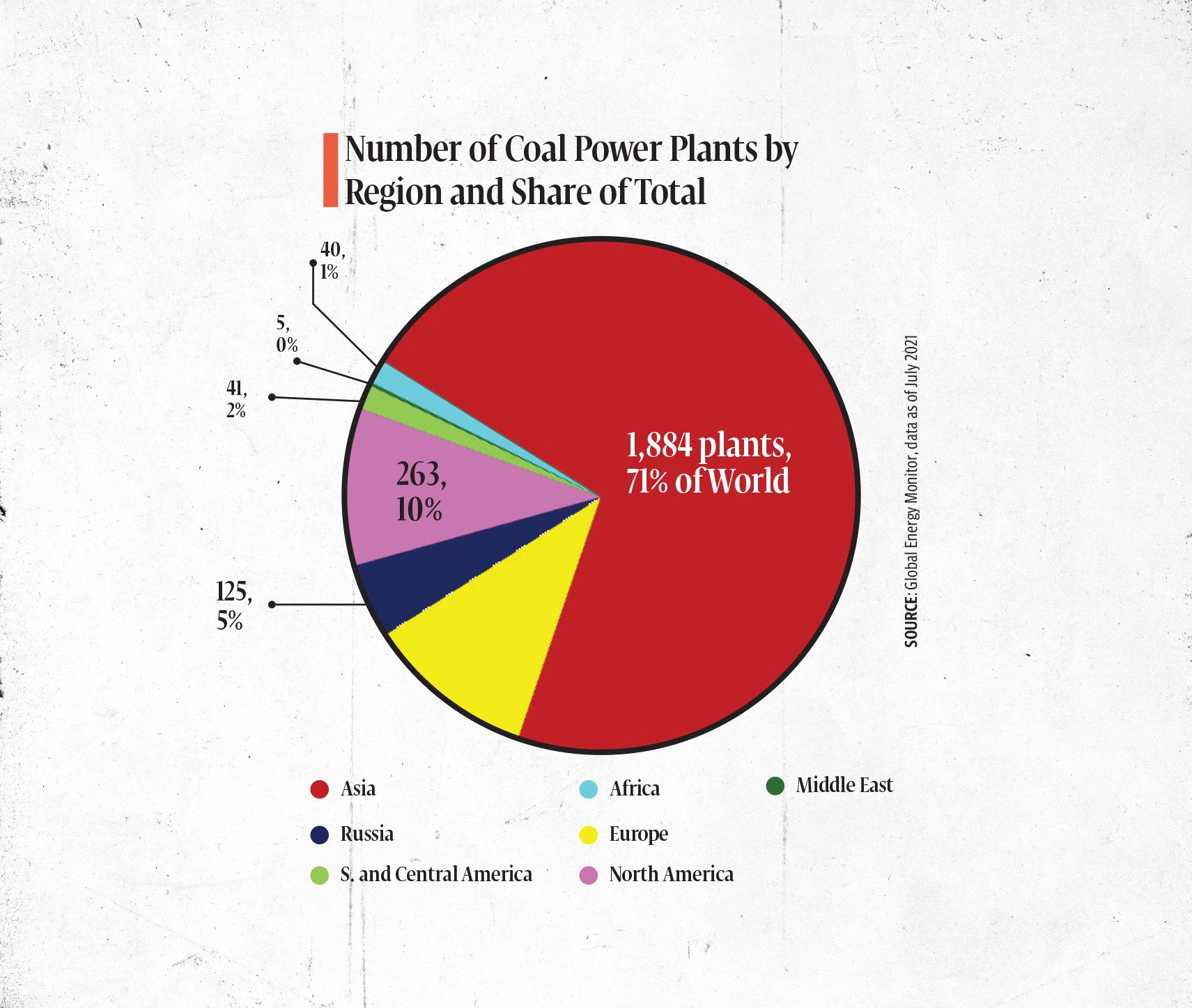

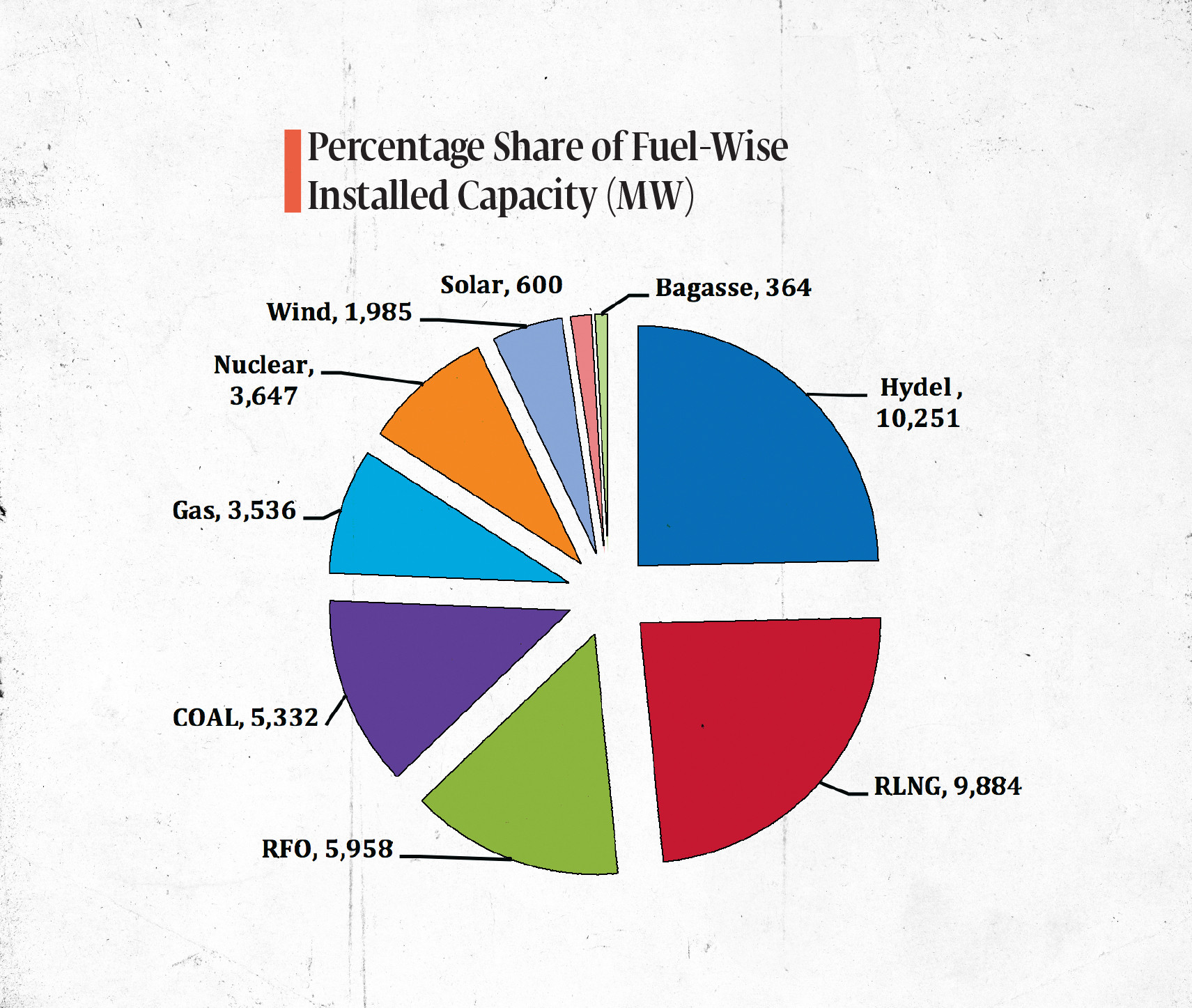

To start with, the government does have a point when it comes to imported fuel resources and their link with high energy prices. Electricity production in Pakistan is heavily reliant on conventional fuels such as gas, oil, and coal, with domestic sources of gas and coal accounting for only 10-11%. The remaining 49% thermal power requires fuel imports, all paid for in dollars. Add the depreciation of the rupee, and the costs just rise further. However, what is not understood is that coal is in terms of rate per unit (imported and local combined), far cheaper than imported fuels (RLNG, RFO and High Speed Diesel), as can be evidenced by the fuel rate merit order list . Therefore, conversion of power plants fuel will be less beneficial than if other fuels were made more self-sufficient. So the government is misleading here by saying coal is the sole reason why our energy costs are high.

Another major issue concerns the construction of power plants. These are also financed by external loans, including interest, insurance, investment costs, and profit margins—collectively referred to as capacity payments. These payments are also made in dollars, and due to political instability and policy inconsistency, the projects are rarely ever completed in time. Those payments then accrue interest due to these delays, meaning more payments in dollars, and more electricity costs. While before much of this was born by the Federal Budget, these costs have now been passed on to consumers.

Thar coal vs imported coal

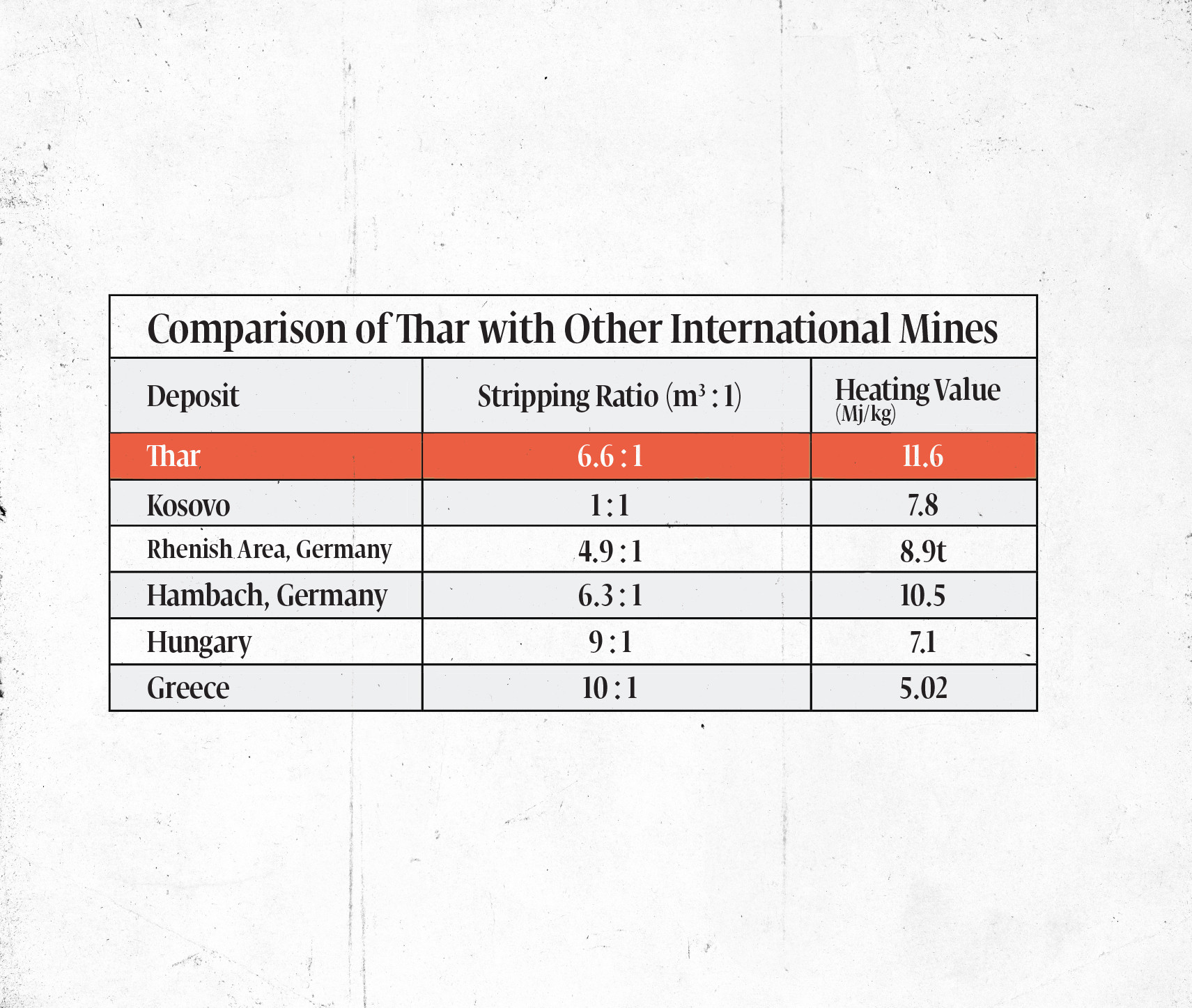

On the face of it, the shift to Thar coal makes sense. Due to it being locally extracted, it will cost $48 per ton, less than half of the amount for imported coal (approx $100 per ton). That means less dependency, and less foreign exchange spending. Win-win, right?

Nope. Once we move past the jingoistic chest thumping and political point scoring, we realize that the issue of moving from imported to Thar coal isn’t that simple. To poorly paraphrase Animal Farm, not all coals are the same, and here’s why:

- Thar coal has a calorific value far lower than of imported coal. In other words, to produce 1 Megawatt of electricity requires one ton of imported coal, but two tons of Thar coal. That in turn means that twice the amount of that coal needs to be transported compared to imported coal, which is logistically quite expensive.

- Thar coal is far more prone to self-ignition, and cannot be stored for long periods. Due to its high moisture content and high sulfur levels, it starts smoldering and emitting smoke within 10 days of exposure to air, making it dangerous particularly during the winter months. We saw a real demonstration of this in March 2022, when an explosion at the Engro Powergen Thar Coal Plant injured five people, causing the plant to remain closed for two months.

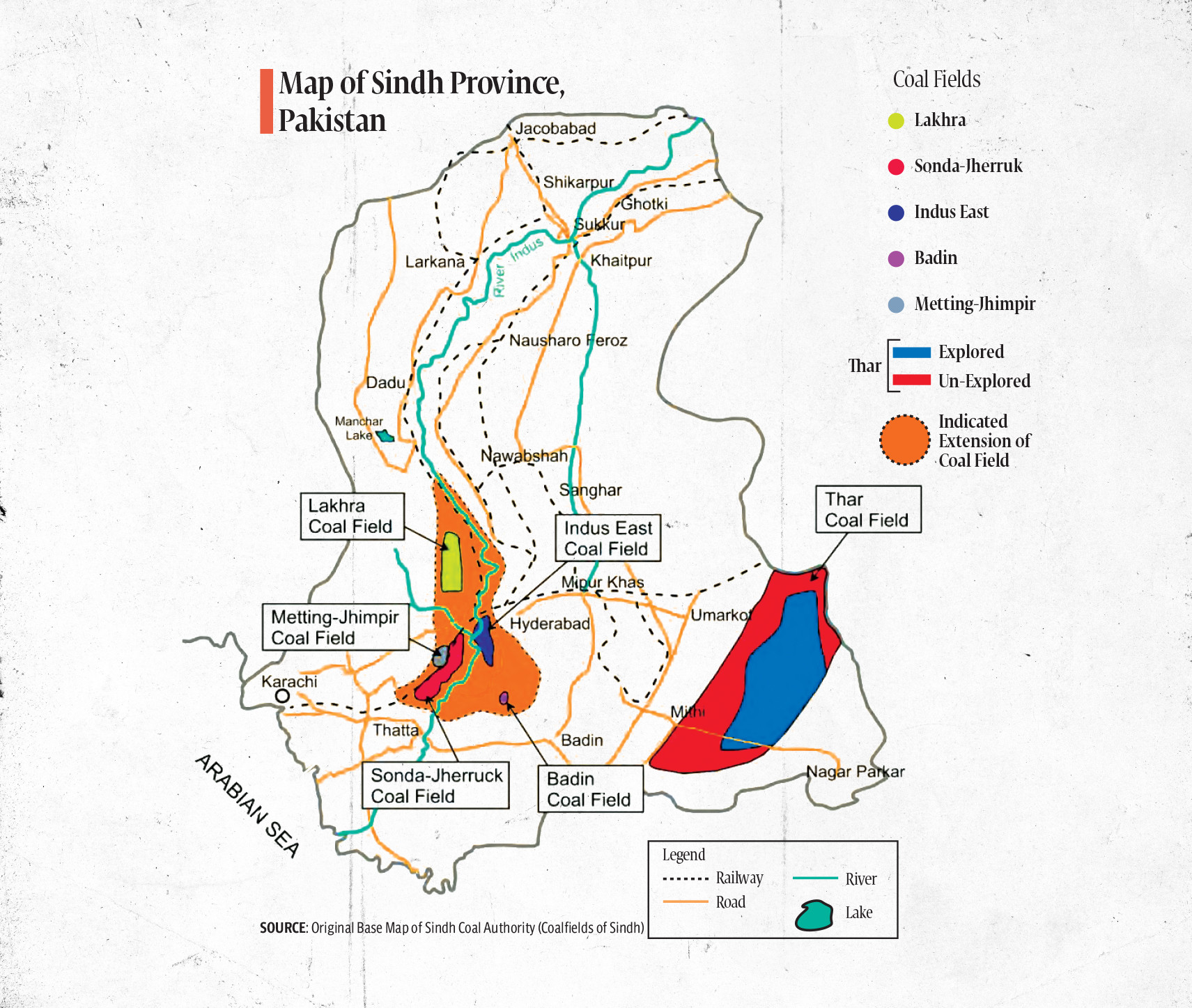

- Thar coal supply and transportation costs are both challenging and expensive. A 2013 survey report by the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) revealed that lignite coal power plants are usually located near coal mines, which is not the case in Pakistan. The key complications are:

- Plants converted to Thar coal will require at least 2 million tons of coal per year per plant, which is quite difficult to fulfill under current production.

- The railways systems lack the capacity to carry the amount of coal needed. Key routes, such as Thar to Karachi, lack any railway line, meaning travelling on trucks, which will have a direct effect on costs.

- Even if we solely rely on railway systems, there is a lack of capacity. For instance, we if are to transport coal to the Sahiwal power plant from the Thar mines, we would need at least 13 trains daily to deliver the load, but Pakistan railways currently has a maximum freight capacity of 6 trains per day. That means longer times and increasing costs.

- As explained above, the longer the coal is left exposed, the greater the chance of self-combustion. Safety is a huge risk.

Supplying vs denying

A largely undiscussed matter is that while the government touts on the massive potential reserves (180 billion tons according to a former Prime Minister), little is mentioned about the amount extracted based on existing resources. Data from the Thar Coal Energy Board shows that the Thar coal mine produces 7.8 million tons of coal annually, barely meeting the fuel demand of the four 2640 mega watt power plants established in Thar. In fact, one of those plants, the Lucky Power Plant at Port Qasim, has already complained of not receiving enough coal to meet their requirements, resulting in lower power output and unexpected shutdowns. As mentioned above, given that coal plants require at least 2 million tons of Thar coal per year per plant, we will need to add at least 6 million more tons annually to supply just the Chinese plants. If the government is already having trouble meeting the existing requirement of 8 million tons, how will it manage 14 million tons? The government seems to be in denial about if this is even possible. Whether this is more than a pipe dream, remains unproven.

Forced conversions?

To convert existing plants from imported to Thar coal is not simply a substitution issue. Much like Shahid Khaqan’s response to NAB on LNG vs CNG storage, the same machines and units used for imported coal cannot be used for Thar coal. For instance, the boilers in the Chinese plants discussed by Prime Minister Sharif are not designed for lignite coal, requiring specially designed boilers, as well as technical mitigation to avoid issues like as tube ruptures, low-temperature corrosion, and reduced production efficiency. That would mean higher operational costs as well. That also means a transition period, whereby these plants will a) not be producing power, further increasing the energy deficit, and b) cost more money by installing new equipment to handle the Thar coal. It’s easy to guess who will bear the brunt of these costs, which are an estimated $2-3 billion dollars for conversion and supply chain set-up as well as additional costs. Given the record amounts the public is already paying in taxation and inflation costs, it’s not difficult to predict how they will react to this.

Even if the conversion does happen, doesn’t mean there’s a success story. A key example is the Jamshoro coal plant, which has managed to partially transition from imported to Thar coal. However, even then, only 20% of the total coal comes from the Thar mines, while 80% is still imported from abroad. One might question why all these exorbitant costs are being paid, just for a fraction of independence?

Even if the conversion does happen, doesn’t mean there’s a success story. A key example is the Jamshoro coal plant, which has managed to partially transition from imported to Thar coal. However, even then, only 20% of the total coal comes from the Thar mines, while 80% is still imported from abroad. One might question why all these exorbitant costs are being paid, just for a fraction of independence?

One option, as the government would have you believe, is to rely on the goodwill of the Pak-China friendship. Given their heavy investment in CPEC, it makes sense for Beijing to support Islamabad on the costing. However, signs don’t appear too friendly. A top Chinese official at a power plant in Pakistan, who shared his views with this author on the condition of anonymity, said that Chinese power companies have already expressed their serious concerns on such conversions, arguing that there is no stable supply chain at present, based on the factors shared above. Hence, Beijing is more likely to give the proposal a blank stare instead of a blank check, and will probably delay the implementation under the pretext of a technical review. That would either give both countries time to assess the viability of the plan, or to abandon the project altogether.

Epilogue

When it comes to Thar coal, it seems a matter more motivated by hearts than minds. The cost of conversion to local coal might be great for generating headlines, but not so for the ugly reality they hide, which will include massive conversion costs, supply chain costs, safety issues, and financing issues. Islamabad will have to do more than generate goodwill for the project to be feasible enough to invest in. Therefore, as much as our Premier would love our penchant for optimism, this isn’t the win he’s looking for.

Muhammad Akmal Khan is an Islamabad-based broadcast journalist and documentary filmmaker. He can be reached via email at akmal.khan@gmail.com

All facts and information are the sole responsibility of the author