Those too young at the time or born after the year 2000 may not know or remember this but we went through a tech panic once. When the Internet still seemed like an uncharted frontier, when Microsoft Windows 98 was your only window to the world wide web and when the sound of a dial-up modem connecting was a familiar background noise, we faced the fear of a looming disaster known as the Y2K bug.

The anticipated glitch was rooted in how computers back then handled dates. Many systems only used the last two digits of the year, so the year 2000 would be indistinguishable from 1900. When the countdown would end, experts feared computers would set their clocks a hundred years back, compromising activities that were programmed on a daily or yearly basis.

As the media counted down the days to the new millennium, it also amplified this panic. Talking heads predicted everything from minor inconveniences to apocalyptic scenarios. Banks, which calculate interest rates daily, faced real problems, as did global transportation services, particularly airlines. Power plants and other technology centres, which depend on routing computer maintenance, also seemed at risk. So companies and governments worldwide scrambled to update their systems, pouring billions of dollars into Y2K compliance projects. People stockpiled supplies, fearing disruptions in essential services or worse – the end of times!

When the clock struck midnight on January 1, 2000, the world held its breath.

In the end, the transition was largely smooth, with only minor glitches reported. A nuclear facility in Japan suffered an equipment failure but nothing that wasn’t mitigated by backups. The US initially thought some Russian missile launches it detected may have been due to the bug, but it turned out those were scheduled ahead of time.

Due to the whimper instead of the expected bang, most people dismissed the Y2K bug as a hoax. It became a historical footnote, with its lesson highlighting our dependence on technology and the potential vulnerabilities of digital systems brushed aside to the far corners of our mind.

What would have happened if some of the worst fears of Y2K had come to pass? As it stands, on Friday last week, the world came surprisingly close to a scenario reminiscent of that panic. On the morning of July 19, banks, businesses, airlines and other essential services suddenly came to a grinding halt for sometime.

The reason? A global IT outage that triggered the infamous ‘Blue Screen of Death’ on millions of machines operating Microsoft Windows when users tried to boot them up. The identical error that popped up on screens around the globe was linked to a single cybersecurity software provider named CrowdStrike.

The company

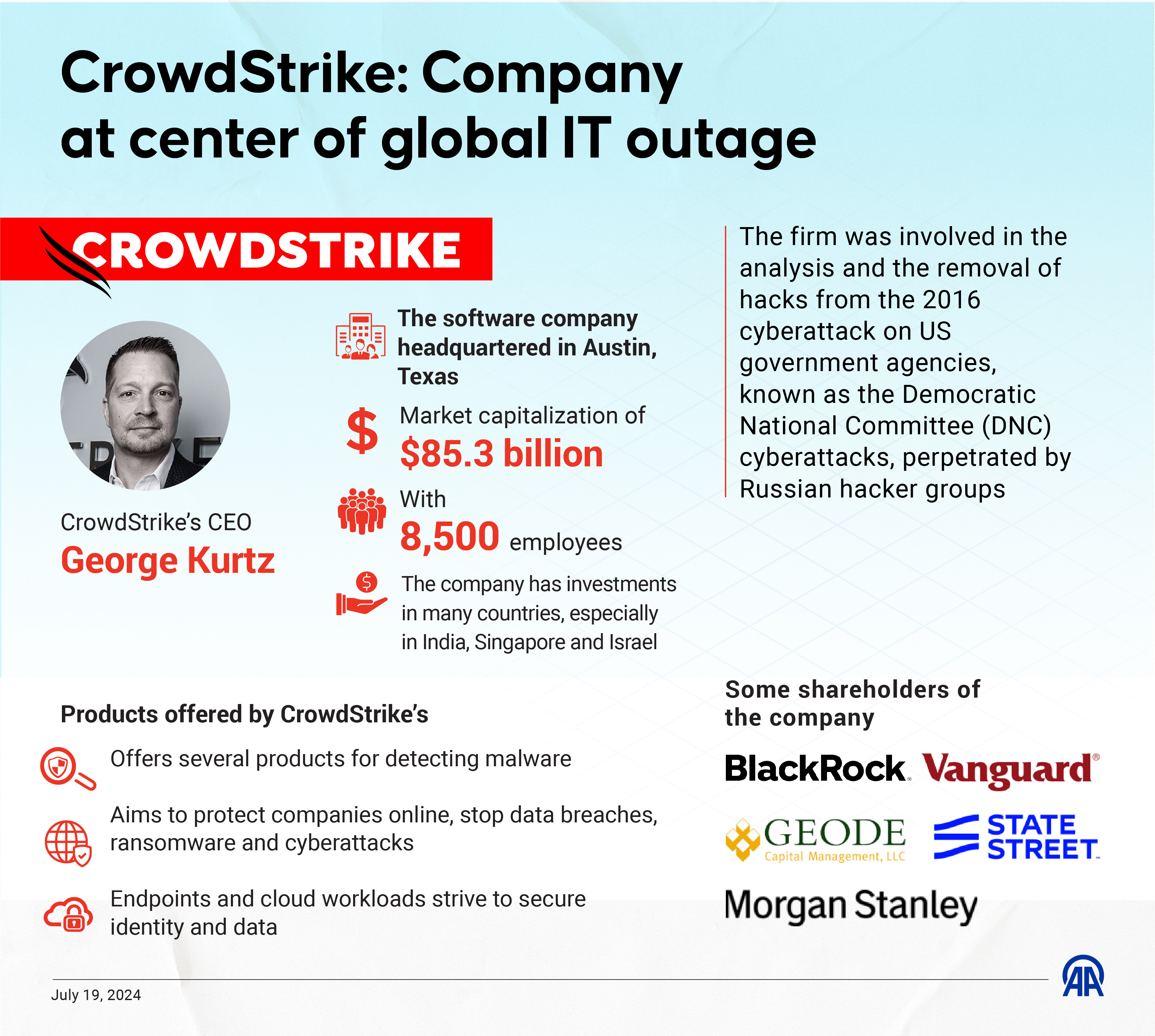

According to media reports and explainers carried by multiple global news sources, CrowdStrike is employed by many top companies to help them find and prevent security breaches. Claiming to have having the “fastest mean time” to detect cybersecurity threats, the company boasts 29,000 customers.

According to the CrowdStrike website, more than 500 of its clients are on the list of the Fortune 1000. Among its key clients – and the reason why millions of Windows users could not boot up their devices on July 19 – is the tech-giant Microsoft.

An article carried by the online publication The Verge stated that the Texas-based company has helped investigate major cyberattacks since its launch in 2011. The incidents included the Sony Pictures hack in 2014, as well as the purported Russian cyberattacks on the Democratic National Committee in 2015 and 2016.

In the 2016 DNC cyberattack, the US Federal Bureau of Investigation reviewed computer forensic evidence provided by CrowdStrike, though the bureau’s failure to warn officials despite findings caused outrage. Meanwhile, Russian officials denied all allegations of interference in the US elections.

Additionally, CrowdStrike stated in the past that cyberattacks perpetrated by Chinese hackers were successfully repelled.

According to Anadolu, CrowdStrike has also made heavy investments in Israeli cybersecurity firms, such as Cybersixgill, DoControl, and Dig Security. In 2020, CrowdStrike acquired the Israeli startup Preempt Security and established a large research and development center in the country two years later. CrowdStrike acquired another Israeli cybersecurity startup, Reposify, and the cloud security startup Bionic for $350 million in 2023. In 2024, CrowdStrike acquired Flow Security for $200 million.

The bug

The bug

Ironically, it was CrowdStrike’s popularity that placed it in the position to wreak havoc on a global scale when something went wrong. The day the outage hit, the company’s CEO George Kurtz announced that CrowdStrike was “actively working with customers impacted by a defect found in a single content update for Windows hosts.”

The July 19 outage was linked to CrowdStrike’s flagship Falcon platform, a cloud-based solution that combines multiple security solutions into a single hub, including antivirus capabilities, endpoint protection, threat detection, and real-time monitoring to prevent unauthorised access to a company’s system.

The update CEO Kurtz alluded to installed faulty software onto the core Windows operating system, causing systems to get stuck in what’s known as a boot loop – a problem that occurs on computing devices when they repeatedly fail to complete the booting process and restart before the sequence is finished, preventing the user from accessing the regular interface. Due to the faulty update, Window’s systems that tried to install it displayed the error message that says, “It looks like Windows didn’t load correctly.” The issue also solely affected machines that operated Windows, with Mac or Linux devices continuing to operate as usual.

The outage and its cost

A blog post by Microsoft published the day after the global IT outage said that the faulty CrowdStrike software update affected nearly 8.5 million Microsoft devices. "We currently estimate that CrowdStrike's update affected 8.5 million Windows devices, or less than one per cent of all Windows machines," it said in the blog. "While the percentage was small, the broad economic and societal impacts reflect the use of CrowdStrike by enterprises that run many critical services," it added in its blog post.

With so many devices across the world left inoperable, a Internet services and a broad swathe of industries worldwide found themselves disrupted, with losses mounting up to billions of dollars. Major airlines were forced to ground their flights, triggering chaos at many of the world’s busiest airports. Banking and healthcare were among the sectors that faced problems due to the issue.

Meanwhile, hackers and cybercriminals sought to capitalise on the confusion, setting up fraudulent websites filled with malicious software to lure in and compromise unsuspecting victims, according to warnings from the US government and multiple cybersecurity professionals. A bulletin by the US Department of Homeland Security said it witnessed “threat actors taking advantage of this incident for phishing and other malicious activity.”

As the dust settled, insurers began calculating the financial damage the bug had caused to alarming results. The insurer Parametrix said the largest IT outage in history would cost Fortune 500 companies alone more than $5 billion in direct losses.

The outage was likely to be "the biggest accumulation event we ever saw in cyber insurance", Parametrix CEO Jonatan Hatzor told Reuters. "This event travelled very fast and was very global."

Hatzor estimated that financial losses globally from the outage could total around $15 billion, as companies struggled to get their computers back up to speed. Global insured losses could total around $1.5 billion to $3 billion, Hatzor added.

Insured losses from the outage will likely total $540 million to $1.08 billion for the Fortune 500 companies, Parametrix said in a statement.

Cyber analytics firm CyberCube calculated global insured losses in a similar range to Parametrix, estimating them to be between $400 million to $1.5 billion. “The outage may be the single largest cyber insurance loss,” it said in a statement, adding that it was "a major event for the cyber insurance market but does not come close to the destructive potential that leading insurers are holding capital against."

Malaysia's digital minister on Wednesday asked Microsoft and CrowdStrike to consider compensating companies that suffered losses during last week's global tech outage. Five government agencies and nine companies operating in aviation, banking and healthcare were among those affected in Malaysia, minister Gobind Singh Deo told reporters, adding that he had met with representatives from Microsoft and CrowdStrike to seek a full report on the incident and ask the firms to take steps to avoid a repeat outage.

"If there are any damages or losses, where there have been any parties that have made such claims, I've asked them to consider those claims and see to what extent they are able to help resolve the issue," Gobind said, adding that the government would also assist on the claims where possible.

On Thursday evening, before it pushed out the faulty update, CrowdStrike’s valuation was upwards of $83 billion. According to a report by the financial magazine Barron’s, the company’s stock lost nearly 26 per cent over the week following the global outage it triggered.

Recovery and aftermath

According to Microsoft, CrowdStrike helped develop a solution that will help Microsoft's Azure infrastructure accelerate a fix. It added that it was working with Amazon Web Services and Google Cloud Platform, sharing information about the effects Microsoft was seeing across the industry. A report by Reuters on Wednesday quoted a source familiar with the issue as saying there is no sign Microsoft Corp plans to limit Crowdstrike's access to the Windows operating system.

By Thursday, CrowdStrike CEO Kurtz claimed more than 97 per cent of Windows sensors were back online, nearly a week after the global outage. "Our recovery efforts have been enhanced thanks to the development of automatic recovery techniques and by mobilising all our resources to support our customers," he said in a post, on LinkedIn.

Even so, the US House of Representatives Homeland Security Committee sent a letter to CrowdStrike CEO George Kurtz asking him to testify on last week's global tech outage. "While we appreciate CrowdStrike's response and coordination with stakeholders, we cannot ignore the magnitude of this incident, which some have claimed is the largest IT outage in history," the congressional panel wrote in its letter to Kurtz dated Monday. The letter was reported first by the Washington Post.

"CrowdStrike is actively in contact with relevant Congressional Committees. Briefings and other engagement timelines may be disclosed at members' discretion," a company spokesperson said.

The risk of monopoly

The risk of monopoly

For a second, let’s time travel back a year to before the Y2K panic days. In 1998 Microsoft, at the centre of last week’s global crisis, found itself across the US Department of Justice pursuing a case with several states. The central claim of the landmark case was that Microsoft created a monopoly through its operating systems, choking competitors like Netscape and Apple.

Ironically monopoly is why last week’s outage wreaked so much havoc across the world. Over the decades following the 1990s, Microsoft has remained the largest supplier of software in the world while retaining a sizeable if not dominant position in other sectors of the global IT industry. Boasting a client like Microsoft, CrowdStrike may not have absolute monopoly in cybersecurity but it could benefit from the perception as a ‘trusted and reliable’ cybersecurity provider par excellence. Both these factors combined on July 19 to create a perfect storm when something went wrong.

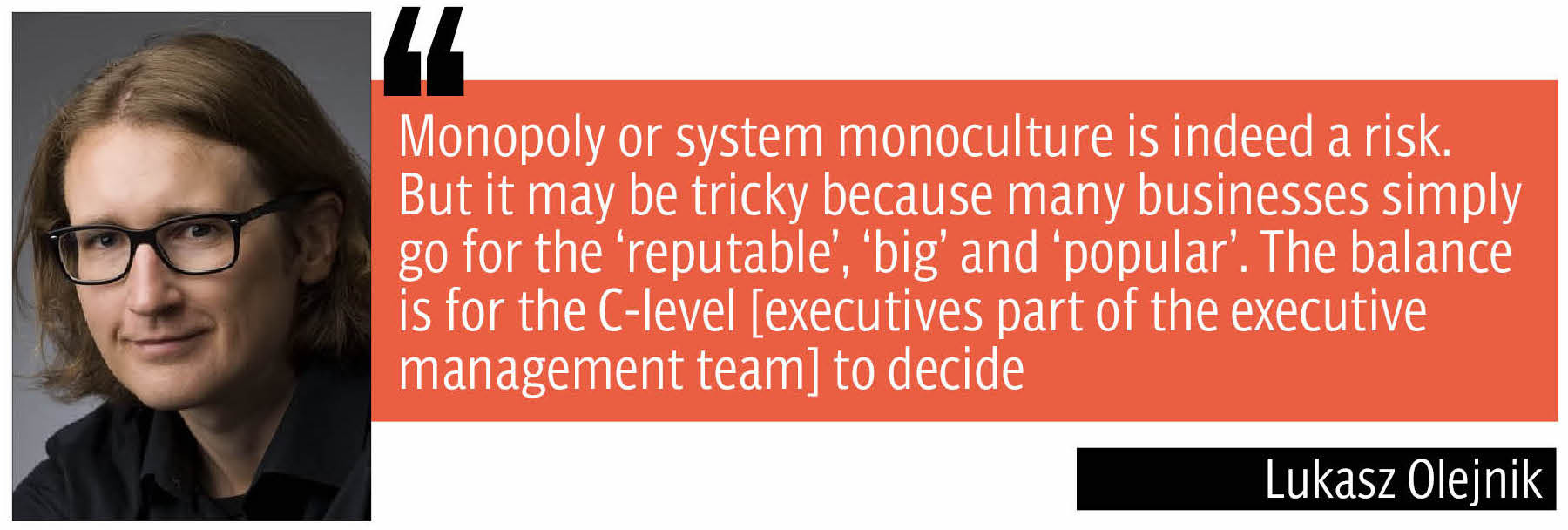

In a piece by The Verge, independent cybersecurity researcher, consultant, and author of the book Philosophy of Cybersecurity Dr Lukasz Olejnik noted, “Our software is extremely interconnected and interdependent… But in general, there are plenty of single points of failure, especially when software monoculture exists at an organisation.”

In a piece by The Verge, independent cybersecurity researcher, consultant, and author of the book Philosophy of Cybersecurity Dr Lukasz Olejnik noted, “Our software is extremely interconnected and interdependent… But in general, there are plenty of single points of failure, especially when software monoculture exists at an organisation.”

Speaking to The Express Tribune, Olejnik said the ‘main takeaway’ of the ‘largest such IT catastrophe to date’ is that companies should be prepared by diversifying suppliers of software and hardware. “The impact is huge… [governments and organisations can better prepare] only by reducing reliance on monopolies such as reliance on specific vendors of operating systems or software,” he explained.

According to Olejnik, this would of course increase costs and could even introduce other cybersecurity risks. “Monopoly or system monoculture is indeed a risk. But it may be tricky because many businesses simply go for the ‘reputable’, ‘big’ and ‘popular’. The balance is for the C-level [executives part of the executive management team]to decide.”

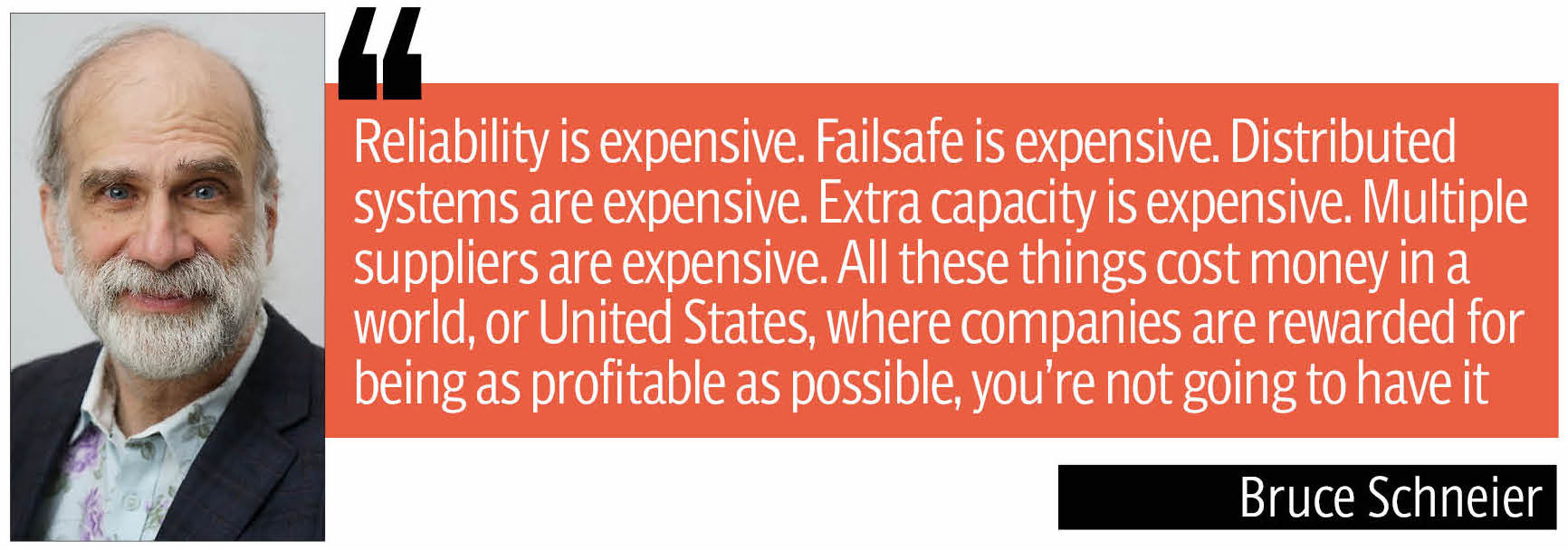

On the topic of monopolisation, internationally renowned security technologist Bruce Schneier said it is a problem everywhere, not just in cybersecurity. “It's a problem in the United States with lettuce. It's a problem with eyeglasses. It's a problem with pharmaceuticals.” He observed that monopolisation and globalisation presents a huge security risk. “It makes things fragile, makes things brittle… as we saw, a single bug can just bring the entire system down.”

Asked how could an economy better prepare for this sort of eventuality, Schneier, who is a lecturer at the Harvard Kennedy School and a board member of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, said, “there are vulnerabilities in our systems because of the consolidation, because of monopolisation.

“We need more resilient systems.…nothing is new here… It's super easy. The problem is it's expensive… no one has any question about how to do this. It costs money. If you want to know how to do it, it's be willing to spend the money,” he stressed. “Reliability is expensive. Failsafe is expensive. Distributed systems are expensive. Extra capacity is expensive. Multiple suppliers are expensive. All these things cost money in a world, or United States, where companies are rewarded for being as profitable as possible, you're not going to have it… the problem is any one of your companies who want to do better, if they do, the CEO will be fired and replaced with a less ethical CEO.”

Asked about the implications of this incident for cloud-based solutions, which more and more tech providers are seeking to push users towards, both Schneier and Olejnik shared their concerns.

“Cloud [services] is[sic] cheaper. You could do the more expensive thing, but again, you're not going to do it,” lamented Schneier. “For cloud, it’s the same. Outsourcing entire companies or business flows mean that the business is critically dependent on the availability guarantees of the cloud vendor. Using various suppliers, or redundancy at a single cloud provider may in principle increase it. This of course comes at a cost,” noted Olejnik.

Some observers have viewed last week’s outage in the context of layoffs in the American tech sector. According to them, shrinking quality control and quality assurance departments, and an increasing belief among corporate IT executives that artificial intelligence could replace human workers could lead to issues like the faulty update.

Commenting on that aspect, Schneier said, “those people [in quality control and quality assurance] are expensive and CrowdStrike had layoffs last year. And I'm sure all CrowdStrike customers had layoffs. Security people are expensive and they're contributing to the bottom line directly.”

According to Olejnik, however, there is little to connect layoffs to the CrowdStrike issue. “I don’t think it’s due to layoffs. Such bugs may simply happen. Layoffs may have complicated the recovery at the impacted firms, though,” he said.

On whether AI can decrease or increase risks, both Olejnik and Schneier viewed the technology as a double-edged sword. “AI could have prevented such an event,” said Olejnik, adding, “AI may be of help, it may also introduce other risk points.” According to Schneier, while AI is cheaper than people and can do some things better, it would not replace people in any way that matters.

On a question about how cybersecurity regulation could evolve in response to incidents like this, Olejnik admitted it is tricky to answer. “Existing cybersecurity regulations may have been understood as requiring to have such EDR (Endpoint Detection and Response) systems like from CrowdStrike. So in fact these systems were being installed to lower cybersecurity risks,” he explained.

Schneier, meanwhile, stressed eliminating single points of failure. “You make sure you don't have single points of failure. But again, that's expensive… Airplanes are designed so if five things break, the plane keeps flying. It is more expensive to build it that way,” he said.

WITH ADDITIONAL INFORMATION FROM REUTERS & ANADOLU