Pakistan’s romance with the Afghan Taliban was bound to turn sour. But it would be this soon, nobody had anticipated. The two sides are drifting away from each other as their relationship has hit the rock bottom over the past few months. At the root of this estrangement lies the Taliban’s reluctance to address Pakistan’s security concerns. And this reluctance stems from their ideological, historical, ethnic, and cultural affinity with the TTP, the sworn enemy of Pakistan. The TTP uses its sanctuaries in Afghanistan’s border regions as a launch pad for its terror campaign in Pakistan. Majority of the recent high impact attacks originated from Afghanistan involving Afghan nationals and modern weapons left by US forces during their chaotic withdrawal in 2021. These include the brazen attacks on military and paramilitary targets in Mianwali, DI Khan, Muslim Bagh, Zhob, Chitral, and North Waziristan. Latest in this terror series was a suicide bombing targeting a bus carrying Chinese engineers in Bisham, Shangla district. Some of these attacks were claimed by TJP or Tehreek-e-Jihad Pakistan, a shadowy group that experts believe was used by the TTP as a ruse to claim deniability in an attempt to give their Afghan patrons an excuse to divert potential Pakistani pressure.

Historically, Pakistan supported the Taliban during the Afghan insurgency in the hope the group would deal with the TTP and other terrorist groups used by hostile agencies during the governments of Hamid Karzai and Ashraf Ghani in Afghanistan. But the hope evaporated into the thin air shortly after the Taliban’s return to power in August 15, 2021. Pakistan, instead, saw a staggering 80% surge in terrorist attacks since then. Pakistani officials have repeatedly called upon the Taliban to rein in the TTP, but the regime remains reluctant due to multiple strategic reasons, triggering unprecedented punitive actions from Islamabad, including cross-border military strikes on terrorist bases, expulsion of illegal Afghans, and tighter border controls. These measures, however, further embittered relations between the two neighbours, triggering border skirmishes and acrimonious exchanges at the political and diplomatic level.

The terror spurt and Taliban’s reluctance to dismantle its sources in Afghanistan have spurred the Pakistani officials to rejig their strategy. A new two-pronged plan they have drawn up involves strengthening internal counterterrorism (CT) effort and dealing with external threat originating from Afghanistan. It also envisages a fresh diplomatic effort to persuade the Taliban regime to address its security concerns. Would this approach work? Senior journalist Ihsanullah Tipu Mehsud doubts.

“It’s wrong to expect the Taliban would give in to any diplomatic pressure because they are not an established diplomatic or political entity. They are a ‘jihadi’ group and their statecraft is driven by their hardline ideology,” says Tipu, who specialises in covering militancy, jihadi movements, and other security-related issues in the AfPak region. “Any persuasive effort should involve tribal jirgas and religious scholars in an independent capacity,” he adds. “Such an initiative should not be state-managed because the official tag would compromise the neutrality of the religious scholars or jirga elders involved and fail to yield the desired result.”

To substantiate his argument, Tipu referred to the failure of the officially sanctioned visit by Mufti Taqi Usmani to Kabul in July 2022. Mufti Usmani and other religious scholars in his delegation were on a mission to dissuade the TTP from its terror campaign in Pakistan. The visit failed to yield anything tangible even though Mufti Usmani enjoys considerable influence in Afghanistan. On the contrary, Maulana Fazlur Rehman had had a productive tour of Afghanistan that he undertook earlier this year in a personal capacity.

Preposterous denial

The TTP has been receiving “significant backing” from al Qaeda and other terrorist groups for executing attacks in Pakistan in addition to support from the Afghan Taliban. The collaboration includes not just the provision of weapons and equipment but also active on-ground support for TTP’s operations against Pakistan, according to the 33rd report submitted to the UN Security Council Committee by ISIL and al Qaeda/Taliban Monitoring Team released in June 2023. “There are indications that the TTP is launching attacks into Pakistan with support from the Taliban,” it adds.

Nonetheless, the Taliban have consistently sought to shift the blame, claiming that the problem lies on the Pakistani side of the border. This denial is preposterous – all the more so because they wouldn’t deny TTP’s presence in Afghanistan when they gathered top leaders of the group, including its chief Mufti Noor Wali Mehsud, to sit across the table with Pakistani officials in Kabul in a peace initiative brokered by the powerful Haqqani faction of Taliban.

“The TTP top cadre is in Afghanistan. There is no doubt about it. Not only the TTP, but the Hafiz Gul Bahadur faction also operates from there. Mid-ranking TTP commanders and foot soldiers sneak into Pakistan in small groups comprising 15 to 30 people to carry out attacks and return to their bases in Afghanistan,” says Tipu.

“A tribal jirga went to Afghanistan in 2022 to negotiate with the TTP. One photo from that meeting featuring Senator Hilalur Rehman from Mohmand district with TTP Jamaatul Ahrar chief Umar Khalid Khurasani went viral on social media. Similarly, another picture of Mufti Taqi Usmani negotiating with the TTP leadership in Kabul also received a lot of traction on social media,” Tipu says exposing the preposterousness of the Taliban’s denial.

Tribal journalist Rifatullah Orakzai agrees with Tipu. “If the TTP didn’t have presence in Afghanistan, then where did its leaders come from to negotiate with Pakistani officials, jirgas, and religious scholars,” says Orakzai, who has been covering the Taliban and TTP insurgencies for more than a decade. “The Taliban never denied TTP’s presence on Afghan soil until the Haqqani-brokered peace initiative collapsed,” he adds. “It was after the failure of this process that the Taliban changed tack.”

TTP’s propaganda wing “Umar Media” used to share videos with Pakistani journalists featuring their fighters cutting the border fence, sneaking in from Afghanistan, and carrying out attacks on Pakistani security forces. “Tellingly, Umar Media stopped sharing such propaganda videos after the Taliban went into denial about TTP’s presence in Afghanistan,” says Orakzai.

Maj Gen (retd) Inamul Haq points to the Taliban’s dilemma. “They don’t have an option. If they accept TTP’s presence on Afghan soil, it would be a violation of the Doha Accord. Plausible deniability suits them because it will be politically suicidal for them to take action against the TTP which enjoys a lot of sympathy in the Taliban rank and file,” he says. “They have been bedfellows during their ‘jihad’ against foreign forces. Any action against the TTP could potentially divide the Afghan Taliban movement and threaten the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (IEA).”

However, the retired general, who has served in the erstwhile tribal belt which was once infested with Taliban fighters, claims that everyone within the IEA is not on the same page vis à vis TTP. “It is politically expedient for them to go into denial. This helps them to deflect Pakistan pressure, hide internal disagreements over the issue, and show unity to outside world,” he says. With all this in view, Inam doesn’t think the Taliban would take any action against the TTP.

Conversely, some experts believe the Taliban might be hosting the TTP and other terrorist groups to use them as a bargaining chip in future dealing with Pakistan and other neighbours. “The continued Afghan tolerance of various terrorist outfits to launch attacks inside Pakistan is deepening Islamabad’s concern that Kabul is deliberately hoodwinking the TTP, maintaining close relations with the terrorist organisation at lower levels and reflects Afghan Taliban’s possible intention to indirectly use it as a tool to attempt blackmailing Pakistan,” says Mohammad Ali, a security expert based in Islamabad.

Leftover weaponry

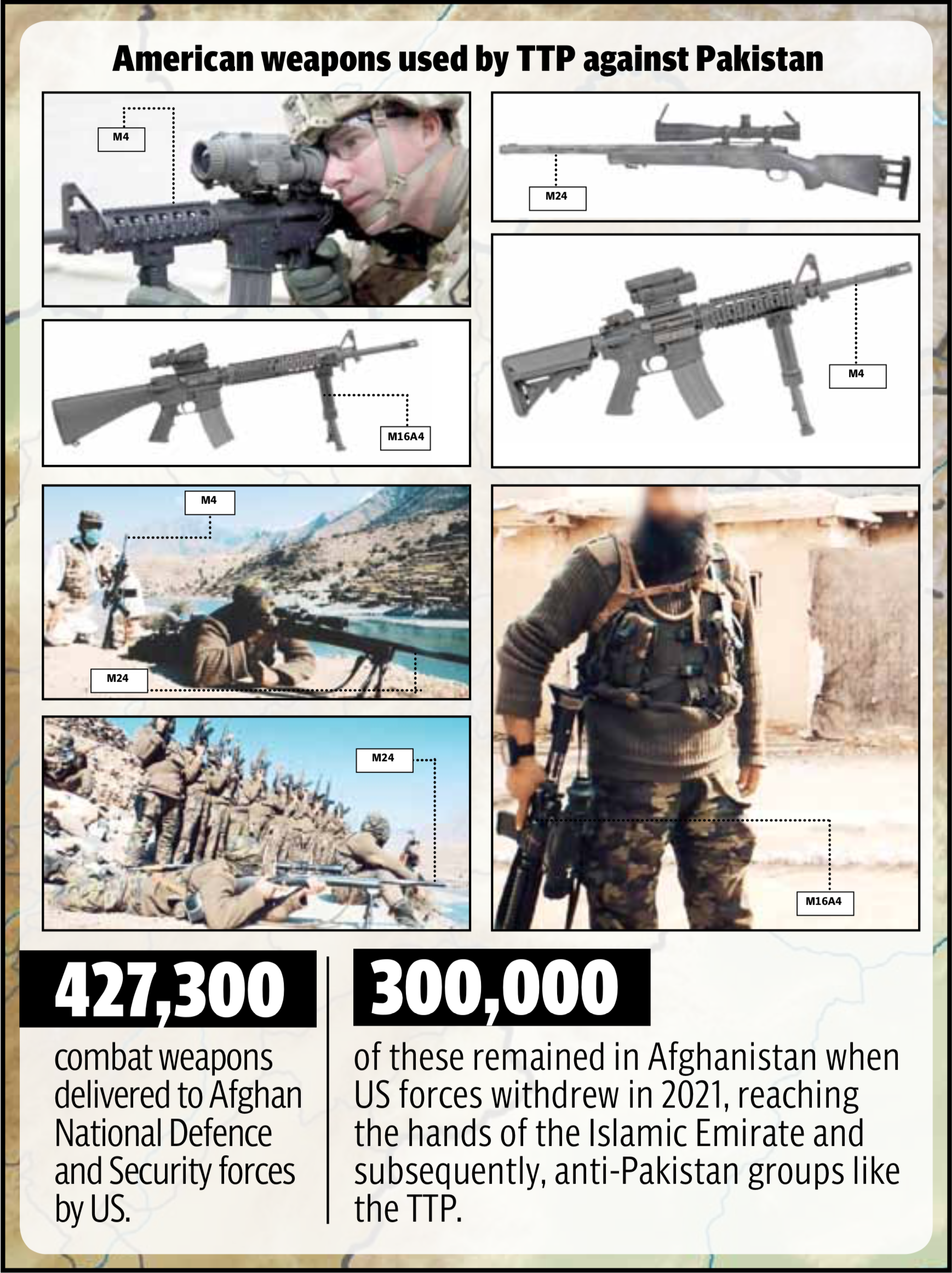

During their frenzied exodus from Afghanistan in August 2021, the US forces had abandoned around $7 billion worth of military hardware and weapons, including firearms, communications gear, and even armoured vehicles. In all, the US delivered 427,300 combat weapons to the Afghan military, and out of these, 300,000 were left in Afghanistan, according to the Pentagon.

US House Foreign Affairs Committee Chairman Michael McCaul revealed in a testimony last year that the Taliban regime armed the TTP. “The TTP, who the Taliban have supplied with weapons that the US left behind, is increasingly conducting terror attacks and al Qaeda remains safely in Afghanistan under Taliban protection,” he said in his testimony.

A video released by ‘ Umar Media’ in August 2022 shows American M24 sniper rifles, M16A4 rifles equipped with thermal scopes, M4 carbines with Trijicon ACOG scopes, DShKM heavy machine guns, and T-15mm heavy 5mm launchers. Prior to this, the TTP shared some photos on May 16, 2023, featuring TTP terrorists training at some undisclosed location inside Afghanistan. The photos showed TTP fighters armed with advanced US weapons, including thermal vision helmets, rifles and laser sights. These weapons were used to carry out terrorist attacks on police and security forces in Peshawar, Lakki Marwat, Bannu, and Dera Ismail Khan.

Pakistan has repeatedly called for an investigation into how the TTP acquired the sophisticated weapons that have greatly enhanced their fighting capacity. The Taliban, however, deny arming the TTP or giving them access to the modern military weaponry left over by the US forces.

Terror export

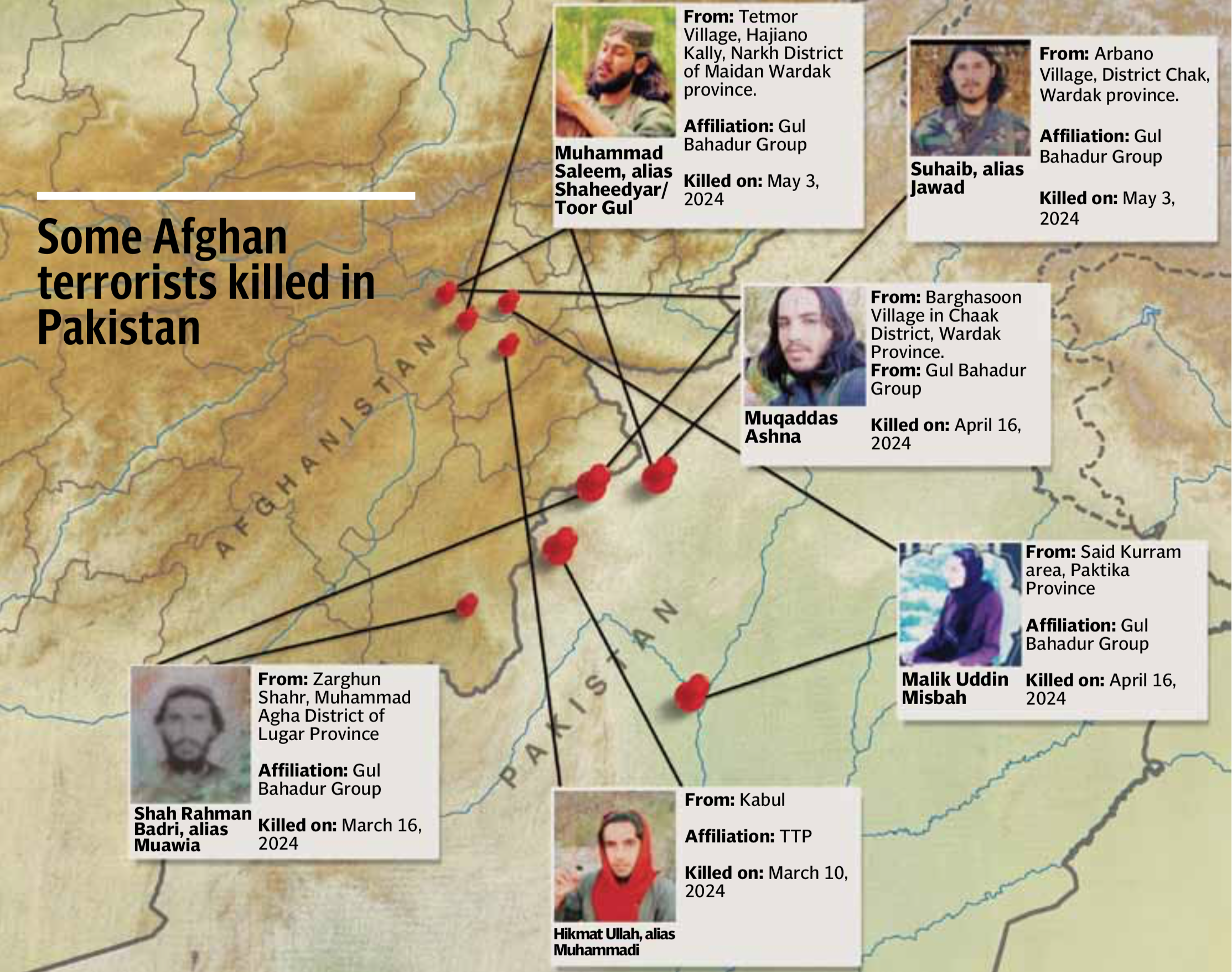

Compelling evidence suggest a symbiotic relationship between the Taliban and TTP. The Taliban are now reciprocating the support they had received from the TTP during their “jihad” against foreign forces in Afghanistan. The TTP not only enjoys complete operational freedom, but also receives modern arms, and finds recruits among the Afghan population. The recent terrorist violence in Pakistan involved several Afghan TTP recruits who were also killed in the attacks they carried out.

The Bisham suicide attack on Chinese engineers was orchestrated from Afghanistan and the bomber involved was also an Afghan citizen. Pakistan’s Interior Secretary Muhammad Khurram Agha travelled to Kabul earlier this year where he met Taliban’s Deputy Interior Minister Muhammad Nabi Omari, shared evidence of Afghan link to terrorism in Pakistan, particularly Bisham attack, and demanded “decisive action” against the TTP. The Taliban mouthpiece, Zabihullah Mujahid, angrily dismissed the evidence as an “attempt to create distrust between China and Afghanistan.”

However, Afghan sources say the Taliban have quietly set up a commission to assuage Pakistan’s growing concerns about the TTP and other terrorist groups enjoying free rein in Afghanistan. This commission is overseeing actions against these groups. “A series of methodical operations targeting the TTP and other anti-Pakistan groups has yielded dozens of arrests. These include fighters from Lashkar-e-Islam who were caught travelling to Khyber from the Afghan province of Uruzgan for carrying out attacks,” says an Afghan government source.

The source further claimed that Afghan forces also raided the headquarters of TTP’s shadow governor for Gilgit Syed Ghazwan in northeastern Afghanistan. A TTP training camp operated by Ghazwan was subsequently shut on Taliban’s instructions. In another incident, Taliban forces raided a TTP camp in the Malakand district of northeastern Kunar province and took two senior commanders identified as Mubarak Bajauri and Pervez into custody. A large number of Lashkar-e-Islam fighters are also imprisoned in Pul-e-Charkhi jail.

However, Orakzai dismisses these actions as a mere eyewash. “After the brazen TTP attack on two Pakistani military check-posts in September 2023, the Taliban regime had rounded up more than 20 TTP fighters in similar operations in an effort to pacify Pakistan. Nothing has been heard of those arrests since,” he says.

Anti-terror purge

The Taliban’s denial of TTP’s Afghan sanctuaries sounds absurd also because some of top commanders of the group have been killed on Afghan soil. TTP founding member Umar Khalid Khorasani, along with three other TTP figures, including Mufti Hassan and Hafiz Dawlat Khan, were killed in a mysterious car bombing in the Afghan province of Paktika in August 2022.

As recent as this month, another TTP founding member Abdul Mannan, alias Hakeemullah, was killed in Kunar. Abdul Mannan was the right hand of TTP leader Azmatullah Mehsud, and played a key role in shaping terrorist operations in Bajaur district, according to sources. Mannan’s killing on June 19 came almost a week after TTP’s attempt to gain a foothold in Balochistan was foiled in a CT effort.

“TTP’s bases in Afghanistan are mainly in the provinces of Kunar, Nuristan, Paktika, Paktia, Nangarhar, and Khost,” says Orakzai. Hence it is not surprising that several TTP senior and mid-level commanders have been killed in these provinces. The question arises who could be behind these killings? “In my personal assessment, these killings could be the result of Pakistan’s CT efforts through local assets,” says Tipu. “These local assets could be from within Afghan Taliban, ordinary Afghan citizens, or even from within the TTP.”

These killings could also be the result of a tug-of-war within the TTP which comprises more than a dozen terrorist groups. Orakzai, however, agrees with Tipu and adds that Pakistan’s patience is wearing thin. “Pakistan now openly carries out CT operations against terrorist hideouts in Afghanistan,” he says.

“In March this year, Pakistan targeted the hideouts of Hafiz Gul Bahadur’s group in Afghanistan to avenge a suicide and gun assault on a military outpost in Mir Ali, North Waziristan,” he adds. “Pakistan’s foreign ministry publicly owned the ’intelligence-based counterterrorism operation’ which triggered hostile actions and inflammatory statements from Taliban officials.”

More such attacks could be in order. Defence Minister Khawaja Asif said earlier this week that Pakistani forces could strike terror havens in Afghanistan because Kabul has been “exporting” terrorism to Pakistan and the “exporters [read TTP]” are being harboured there.

Taliban’s predicament

The Taliban, who morphed from an insurgent group into de facto rulers of Kabul, had greatly benefited from TTP’s hospitality during their “jihad” for more than 20 years. Now, the Taliban are between a rock and a hard place. “Going after the TTP will be politically suicidal for them,” says Inam. “And inaction undermines their efforts for global recognition.”

Tipu believes there are ideological, organisational, cultural, tribal, ethnic, and religious reasons for the Taliban’s reluctance to crack down on the TTP and other transnational terror groups. “Three years ago, TTP chief Mufti Noor Wali wrote a book titled “Inqilab-e-Mehsud” detailing how the TTP was formed by the Afghan Taliban and al Qaeda,” adds Orakzai.

He recalls what senior TTP leader Maulvi Faqir Muhammad had told him after his release from a Kabul jail in August 2021: “How can they [Afghan Taliban] expel us from Afghanistan. We had sacrificed 7,000 lives for them [Afghan Taliban] in US drone strikes and Pakistani military operations.”

Drifting away

Afghanistan, a landlocked country, heavily relies on transit trade through Pakistan. The two countries have five joint border crossings: Torkham, Spin Boldak, Ghulam Khan, Dand-e-Patan, and Angoor Ada, for bilateral and transit trade. Pakistan has been using its leverages, including the transit trade, to persuade the Taliban to rein in the TTP. However, Kabul’s de facto rulers instead of assuaging Pakistan’s security concerns are trying to look for ways to minimise their reliance on Pakistan for trade with outside world.

The Afghanistan Chamber of Commerce and Investment says there is a need to diversify their trade because of the “frequent problems” created by Pakistan. “Afghanistan has alternative ways and we want to expand relations with regional and neighbouring countries,” said ACCI’s first deputy Mohammad Yunus Momand. Wakhan Corridor and Chabahar Port are being tipped as potential alternatives.

According to Reuters, India has leveraged the use of Iran’s Chabahar Port to enhance the transportation of commercial and transit goods with Iran, Afghanistan, and Central Asian states, positioning it as an alternative to Pakistan’s Karachi and Gwadar ports.

India’s recent initiative to develop Chabahar Port has been welcomed by Afghan traders for boosting regional trade and transit. The Taliban regime has already committed a $35 million investment in Chabahar Port that includes construction of various projects, including commercial and trade complex. This also envisages plans to develop a 25-story residential skyscraper in Chabahar, while a special economic zone for Afghanistan is being established at Chabahar.

However, some Pakistani experts do not favour the Taliban’s attempt to find alternative access to international waterways for trade. "The Afghan Taliban's attempt to avoid its international commitments, ambivalence towards Pakistan's terrorism related concerns and attempts to circumvent its eastern neighbour to seek alternative trade and economic routes tantamount to betrayal of Islamabad's longstanding support and goodwill towards the Afghan nation,” says expert Muhammad Ali.

“The current Afghan approach could cause long term damage to Kabul-Islamabad's bilateral ties, deepen Afghan nation's economic plight and further harm Afghan Taliban's efforts to gain international legitimacy and recognition," he adds.

Inam, however, doesn’t think Afghanistan can financially and commercially decouple itself from Pakistan so easily or quickly. “The traditional trade corridor from Central Asia to erstwhile British India via Afghanistan is routed through Pakistan. It wouldn’t be easy for millions of people who have historically been associated with trade through this corridor to reorient a new trade route,” he says.

The ethno-linguistic, historical and religious ties between Pashtun people on both sides of Durand Line are strong enough to give in so easily. Moreover, Inam says it would require massive amount of resources and time to build the road and rail infrastructure required for making Chabahar Port an alternative to Karachi Port.

Having said that, Inam doesn’t foresee a complete divorce between Pakistan and Afghanistan anytime soon as he believes the current rough patch in their ties is transitory. “There are imperatives and variables in international relations. In the AfPak context, we have historical, ethno-linguistic, geographic, and religious imperatives. Our variables are few: TTP, Durand Line, and border fence,” he says.

Currently, the “TTP variable” is holding all “imperatives” hostage. Addressing this could easily help the two neighbours tide over this rough patch in their ties. As a sovereign nation, Afghanistan has a right to diversify its trade options, but at the same time its de facto rulers cannot ignore their international obligations and let their country become the epicenter of terrorism and threaten its neighbours. They need to understand that it is unwise to barter away their crucial relationship with Pakistan in exchange for a group which will ultimately become a geostrategic liability for them.

With additional reporting by Shahabullah Yousafzai