On a sweltering May afternoon, Ahmad Rehan left his office in Islamabad, drenched in sweat from the oppressive heat. Seeking a moment of respite, he decided to stop by a tea point at Quaid-e-Azam University, Islamabad. Despite the scorching sun seemingly intent on baking everything in sight, he persevered, slowly sipping his tea. The air was thick and unforgiving, the kind of heat that seemed to cling to every part of him.

After finishing his tea, Rehan, a practicing young lawyer who resides near the university, sought refuge in the university library to cool off and review his cases for the following day. The library's air conditioning provided a temporary relief from the relentless heat outside. As the library's closing time approached, Rehan, still feeling the day's heat weighing heavily on him, contemplated dinner but found he had no appetite. Instead, he trudged back to his room. Upon reaching his room, Rehan collapsed onto his bed, intending to rest for a few minutes. When he eventually stood to head to the washroom, he only managed a few steps before everything went black. He collapsed at the threshold, unconscious. He lay there for about 15 minutes until Inzimam, a guy living in a room next to Rehan’s, discovered him. Acting quickly, Inzimam administered a saltwater solution and sprinkled water on Rehan's body, slowly reviving him. Rehan and Inzimam live in a shared apartment.

"I felt like my entire body was on fire. The headache was excruciating, and the dizziness was overwhelming," Rehan recounted later how he felt before he lost consciousness. Rehan’s experience is a reminder of the harsh reality faced by countless others across Pakistan, where heatwaves in summer have become a common, life-threatening occurrence.

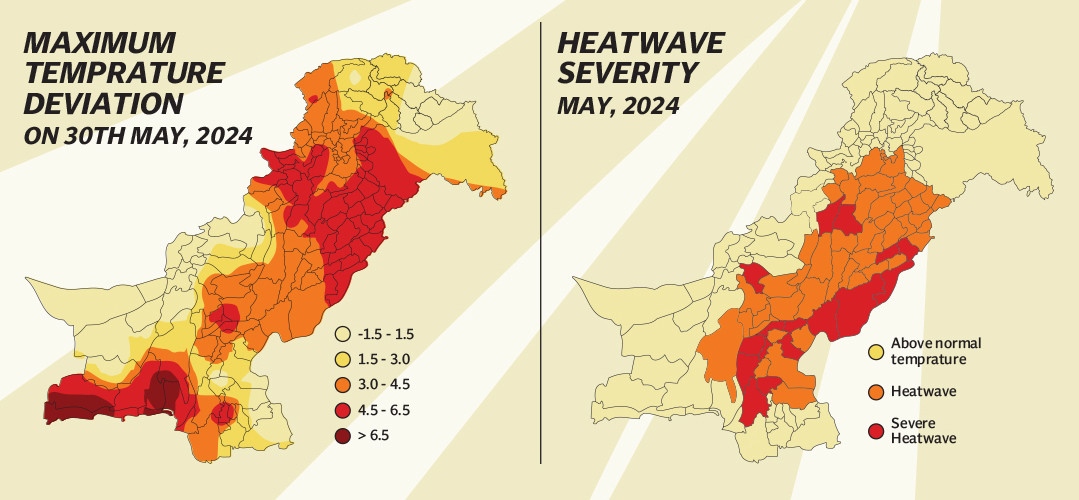

Early in May, the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) warned of heatwaves taking over parts of the country. NDMA issued alerts for Umerkot, Tharparkar, Tando Allahyar, Matiari, Sanghar, Bahawalpur, and Rahim Yar Khan. The authority warned of three potential heatwaves affecting the country: one in May and two in June. Between May 15-30, temperatures were expected to rise to around 40°C, and in June they could climb to 45°C. However, temperatures in Sindh exceeded the predicted mark, reaching an astonishing 53°C in May, with Larkana and Mohenjo Daro becoming the hottest places in Pakistan. The heatwave in May finally gripped 26 districts in Punjab, Sindh, and Balochistan. The Pakistan Meteorological Department (Met Office) also warned that temperatures in northern and northwestern Pakistani areas would be 4-6 °C higher than normal for a week.

Scientists often use the terms "heatwave" and "extreme heat" interchangeably to describe the same phenomenon – a period of abnormally hot weather.

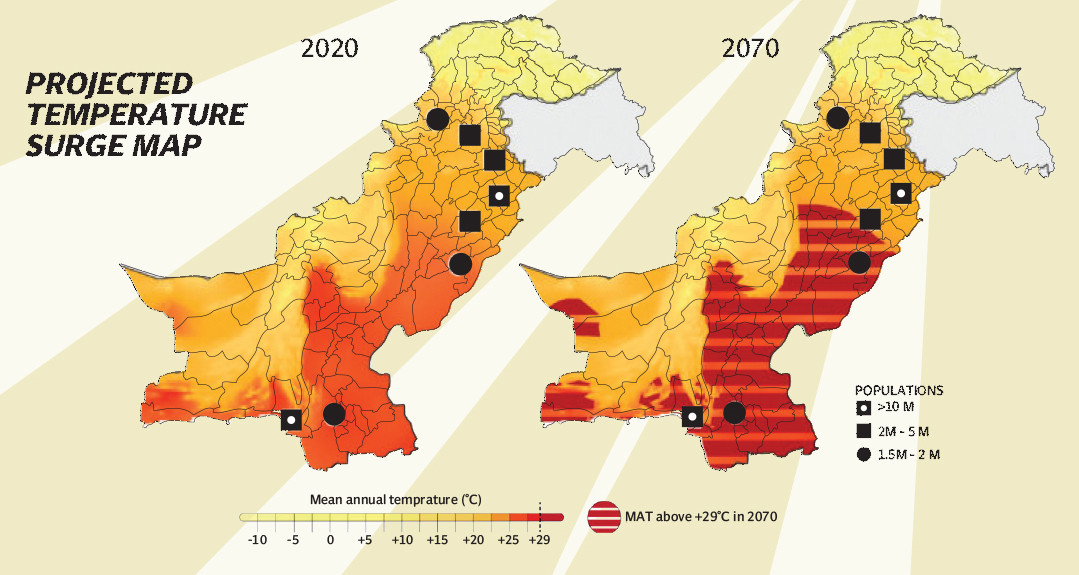

In the last 50 years, the annual mean temperature in Pakistan has increased by roughly 0.5°C. The number of heatwave days per year has increased nearly fivefold in the last 30 years. By the end of this century, the annual mean temperature in Pakistan is expected to rise by 3°C to 5°C for a central global emissions scenario, while higher global emissions may yield a rise of 4°C to 6°C. The Asian Development Bank revealed these findings in a 2017 report titled “Climate Change Profile of Pakistan”.

Temperatures rising

Climate change is dramatically raising temperatures across the globe, and Pakistan is no exception. “This May (2024) was the hottest May in Pakistan since 1961, in which the average mean temperature rose 1.5% higher than the average temperature observed in May in previous years – a clear deviation from normal pattern. This deviation indicates that heatwaves are indeed induced by climate change,” explained Naseer Memon, a senior climate change expert.

Although Pakistan has been experiencing rising temperatures for quite some time, these instances are now becoming more frequent. “Extreme heat is not something surprising; scientists have been warning for decades of extreme heat events, but what is happening right now is more frequent and prolonged. There are multiple days in a year when the temperature reaches extreme levels, which is concerning,” said Amna Shafqat, a climate change research consultant with Oxford Policy Management. In June 2023, temperatures exceeding 40°C led to 22 deaths from heatstroke and exposed millions of people to health risks in Karachi. In 2018, a heatwave killed 65 people in just three days in Karachi. In 2015, Karachi experienced a devastating heatwave that resulted in over 1,200 deaths, leaving another 50,000 sick.

The highest temperature recorded in Pakistan was in 2017 when the temperature rose to 54 °C (129.2 F) in the city of Turbat, in Balochistan. This was the second hottest in Asia and fourth highest in the world.

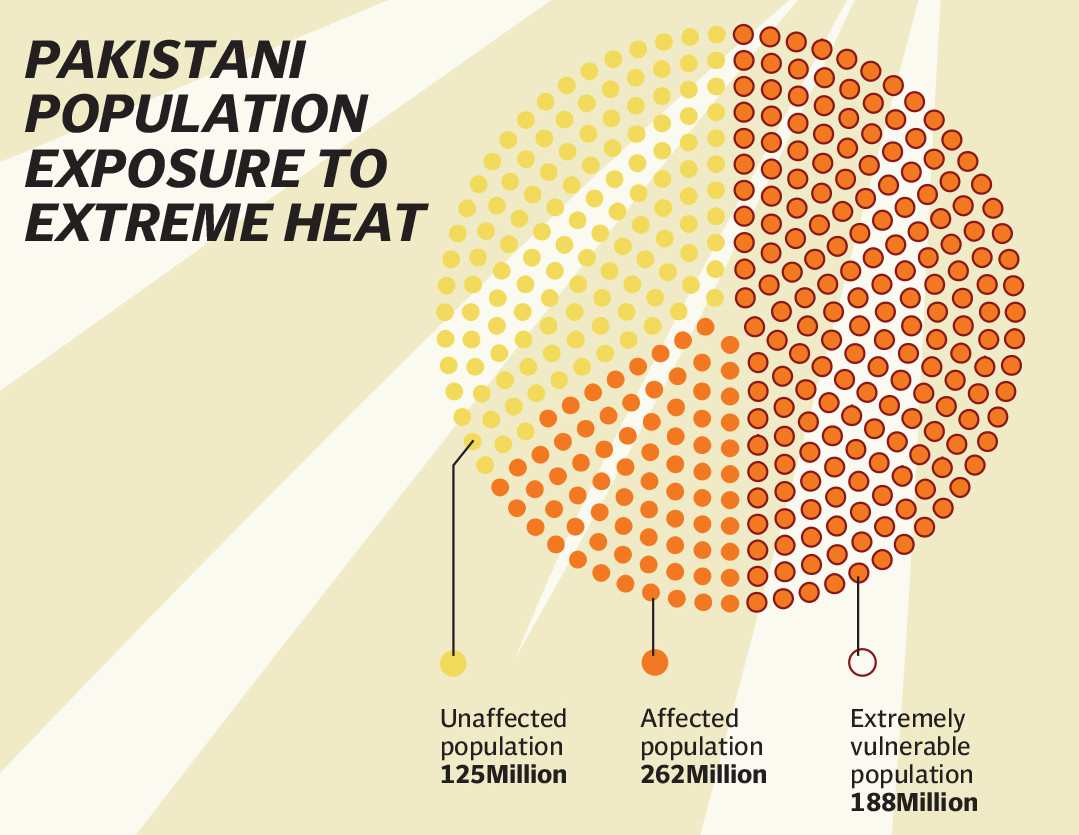

As the emission of greenhouse gases continues unabated, heat is highly likely to increase further in the future. This would impact more people if no heat-preventive measures or plans are in place.

Disruptive summers

Heatwaves in the summer months disrupt normal daily life in Pakistan. In May, the Punjab authorities shut down schools, leaving some 26 million children out of school – more than half of the country’s schooled children. The education department in Punjab cited a temperature surge and a prolonged heatwave as reasons for shutting down all public and private schools across the province. Searing heat can also harm the economy. “Productivity level plummets as people cannot work during heatwaves and cannot go out of their homes, causing an economic slowdown,” said Naseer.

Heatwaves trigger additional disasters in their aftermath. In 2022, between March and May, parts of Pakistan witnessed some of the highest temperatures of over 50°C, with the authorities reporting 65 fatalities. The heatwaves were followed by destructive monsoon rains, glacial lake outbursts and flash floods that affected 33 million people, claimed over 1,700 lives, and damaged or destroyed more than 2.2m homes. Approximately one-third of Pakistan was submerged, leading to the destruction of businesses and an economic loss of more than $10 billion. A World Weather Attribution (WWA) study found that climate change made the 2022 heatwave 30 times more likely.

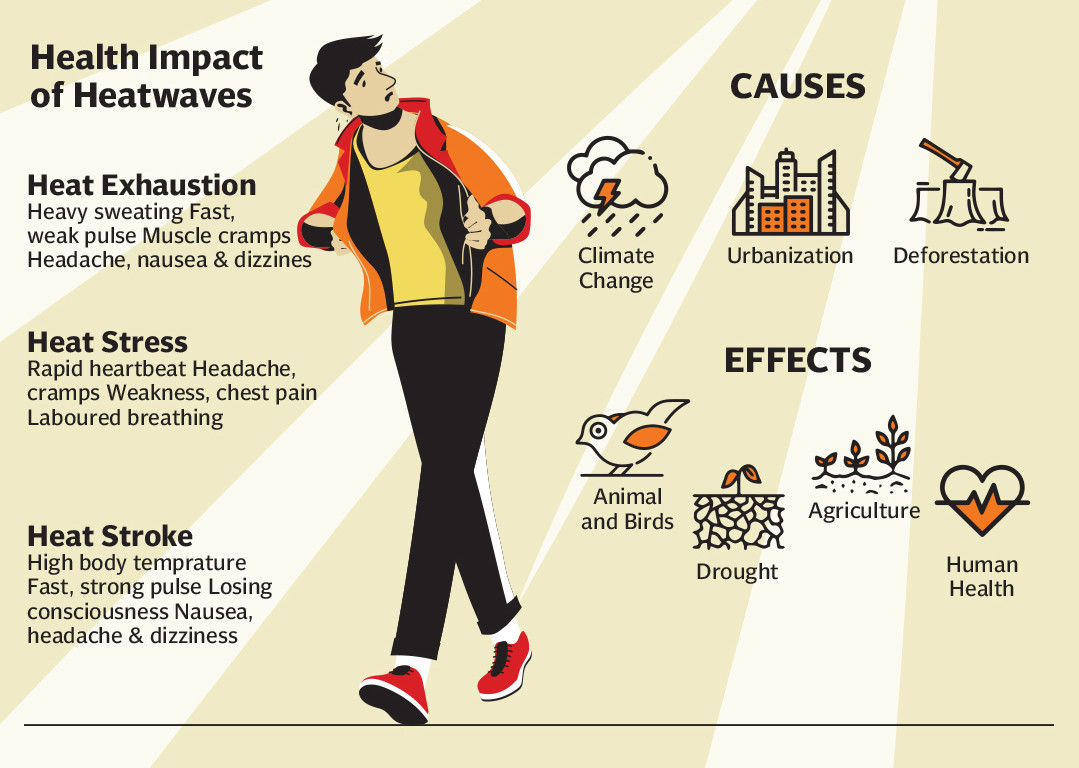

Extended duration of extreme heat can also lead to drought by drying up lakes, rivers, and underground freshwater reservoirs. In May, the Met Office warned that the heatwave in May could lead to a flash drought in the country's southern region in June and ahead, which could have damaging effects on crops and animals. Additionally, the International Rescue Committee (IRC) cautioned that severe heatwaves could worsen food insecurity for 8.6 million people who are already experiencing hunger.

On the other hand, besides heatstroke, extreme heat can lead to various other health problems: acute kidney injury, adverse pregnancy outcomes, worsened sleep patterns, impacts on mental health, worsening of underlying cardiovascular and respiratory disease, and death. Hundreds of people were reportedly treated for heatstroke in Lahore and Multan in Punjab, while scores were brought to hospitals in Hyderabad, Larkana, and Jacobabad districts in Sindh in May.

Azizullah, a hotel owner in Islamabad said that one of his friends, Hazrat Ali, lost his life in Karachi on May 20 due to heatstroke. Ali was working as a laborer with a construction company in the MPR colony. Azizullah himself worked there once. “The heat at the construction site roasts…the ground breathes excessive heat in summer months…you can feel the unbearable heat destroying your insides,” Azizullah told The Express Tribune.

Climate injustice and heat vulnerability

While Pakistan has contributed very less to global warming, a mere 1%, it has been impacted in an unjust and significant way by climate-induced phenomena, such as extreme heat. Pakistan ranks fifth among the countries most affected by global warming. However, Pakistan cannot be absolved from its own failures. “The 2022 flood occurred due to the greenhouse gas emissions generated by the global north and the climate change that they [global north] are responsible for but the flood could have been less damaging had Pakistan been better at water governance; had Pakistan invested in climate change adaptation; had Pakistan at least evaluated how its structures were vulnerable to climate change,” said Maryam Jamali, co-founder of Madat Balochistan.

Additionally, the Pakistani people are confronted with a staggering 15-fold higher risk of death from climate-related disasters compared to other countries.

Vulnerability to heatwaves is contingent upon an individual's socio-economic status within the society. People who are living in poverty and working in the informal sector with precarious work, lower incomes, and fewer opportunities for rest and shade, with limited or no access to support, are more severely impacted by the extreme temperatures than people who are affluent and can switch to better ways of earning income.

Various other elements play a role in raising people’s susceptibility to heatwaves in Pakistan. For instance, more than 40 million people do not have access to electricity. Others have erratic and irregular supplies. Additionally, people living in poverty do not have even access to, or are unable to afford, electricity for fans or air conditioning units, and neither can they afford to buy solar panels.

“The international community needs to fulfill its commitments to provide aid and conditional loans to Pakistan. The amount of aid and climate finance currently reaching Pakistan is insufficient. However, Pakistan also needs to establish monitoring and verification systems for incoming climate aid. Currently, there is no connection between the socioeconomic data of Benazir Income Support Program (BISP) and the climate change data of NDMA. Establishing a connection between them would allow us to determine which populations are actually affected by climate change. This information would help Pakistan access climate finance and international aid more easily, as we would be able to use the data to show how many people are affected,” expressed Amna.

The way forward

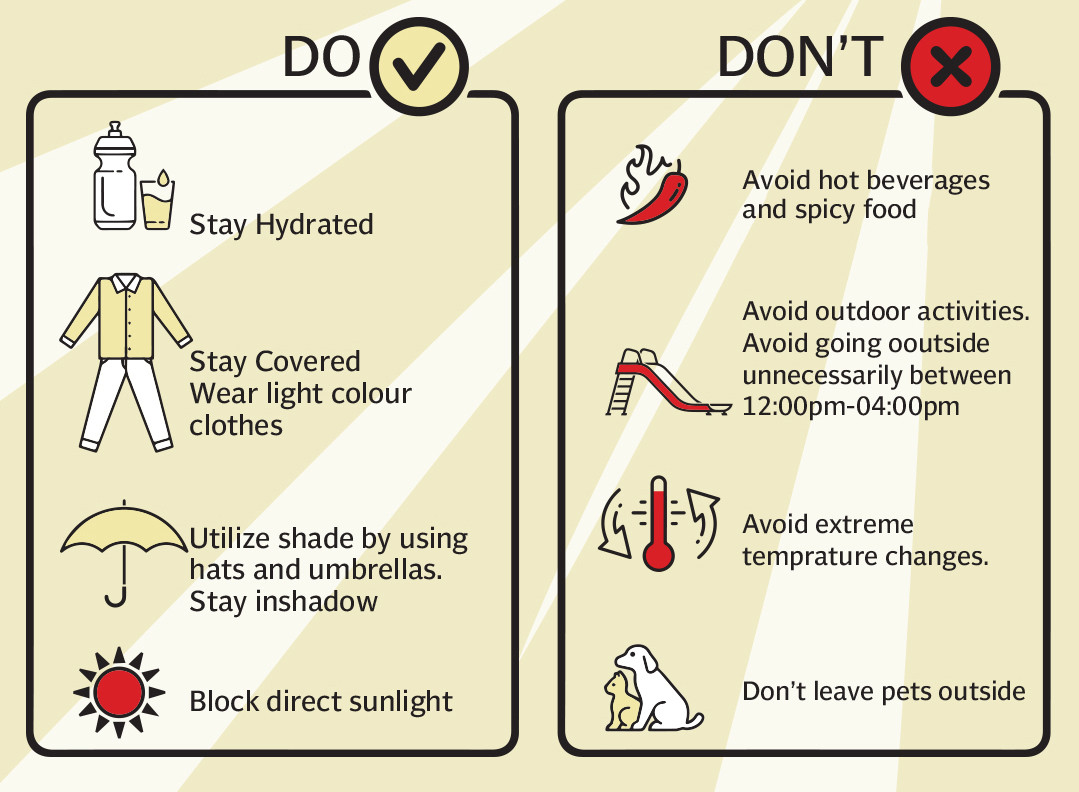

Extreme heat, a consequence of climate change, is anticipated to become more frequent and prolonged, extending far into the future. Therefore, it is crucial to implement measures to mitigate its impact on human life. “There should be arrangements of shade and cold water in public places, as well as access to emergency medical facilities in case someone faints or suffers from heatstroke and requires immediate assistance. Public awareness is critical. Timely warnings should be issued to alert people about rising temperatures and locations that could be affected, so they can take necessary precautions. Public education on preventive measures during extreme heat, such as covering heads and increasing water intake, is also vital. A long-term solution is to increase green cover by planting more trees and incorporating better insulation in construction materials used for buildings,” recommended Naseer.

Pakistan also needs to invest in climate-resilient infrastructure and explore alternative solutions tailored to various regions and demographics to mitigate the impact of future heatwaves. “Although Pakistan is neglected in the global climate change discourse, it needs to take some responsibility for why the Pakistani people are so vulnerable to extreme heat. Pakistan needs to invest in climate-resilient infrastructure, i.e. adaptive housing. Every region in Pakistan has a geographic, socioeconomic, and political context – all of which need to be evaluated before we move forward with any plan. It is also crucial to take into account marginality and vulnerability, and to adopt an intersectional approach towards development efforts. Simply relying on top-down climate finance models is no longer adequate for constructing resilient communities. Without decentralised finance and devolved decision-making, Pakistan will continue marginalising the communities that bear the brunt of extreme weather events such as extreme heat. Moreover, there should be less reliance on privately owned cars and more investment in public transport,” proposed Maryam.

She also emphasised the importance of placing Indigenous people at the forefront of these discussions, ensuring they have a meaningful role in decision-making processes rather than being tokenised for diversity and inclusion. She pointed out that bureaucrats often lack the ability to see beyond rigid structures, whereas local communities, with their deep understanding of their land and context, can offer innovative solutions that outsiders cannot envision.

To protect against climate-induced disasters like heatwaves, Pakistan needs a cohesive strategy integrating infrastructure development, healthcare, education, and community engagement across all regions, contexts, and demographics.

Osama Ahmad is an Islamabad-based freelance journalist and researcher. He writes about democracy, human rights, regional security, geopolitics, organised crime, technology, gender disparities, political violence, militancy, conflict and post-conflict, climate change, and ethnic nationalism. He posts on X at @OsamaAhmad432

All facts and information are the sole responsibility of the author