One thing that fascinates me about history is how it links the past and present. If you stop past the tunnel on the road from Mardan to Malakand and look down a reentrant, you may see the remains of a track that is called the Buddhist Road. I first heard of it from my father Maj Gen Shahid Hamid on one of our many visits to Swat during the 1960s, where the Wali Ahad Miangul Aurangzeb and his charming wife Naseem hosted us. My father was well acquainted with the subcontinent's history and would always tell us about the historical significance sites and places we traveled through.

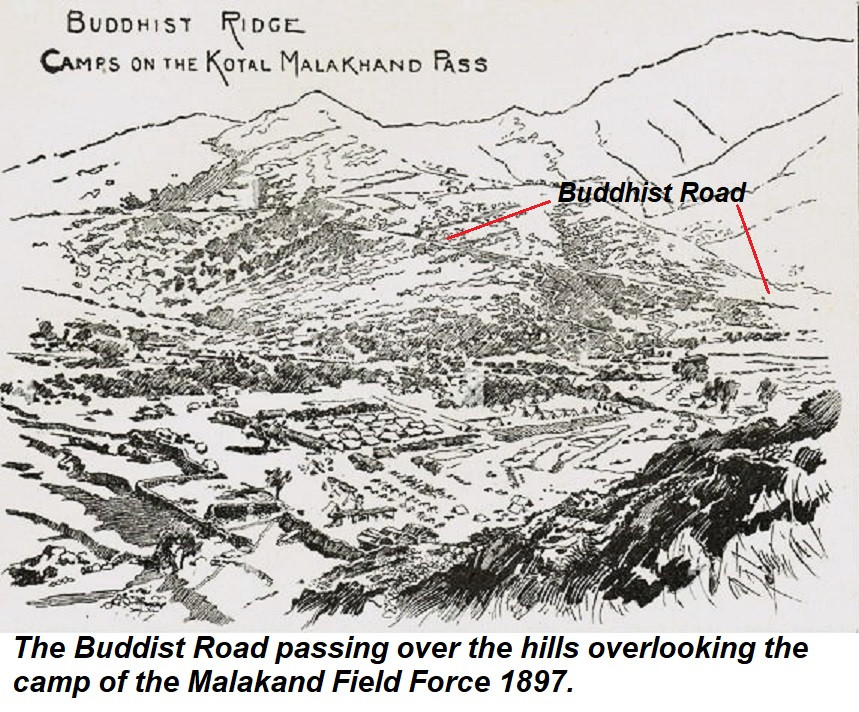

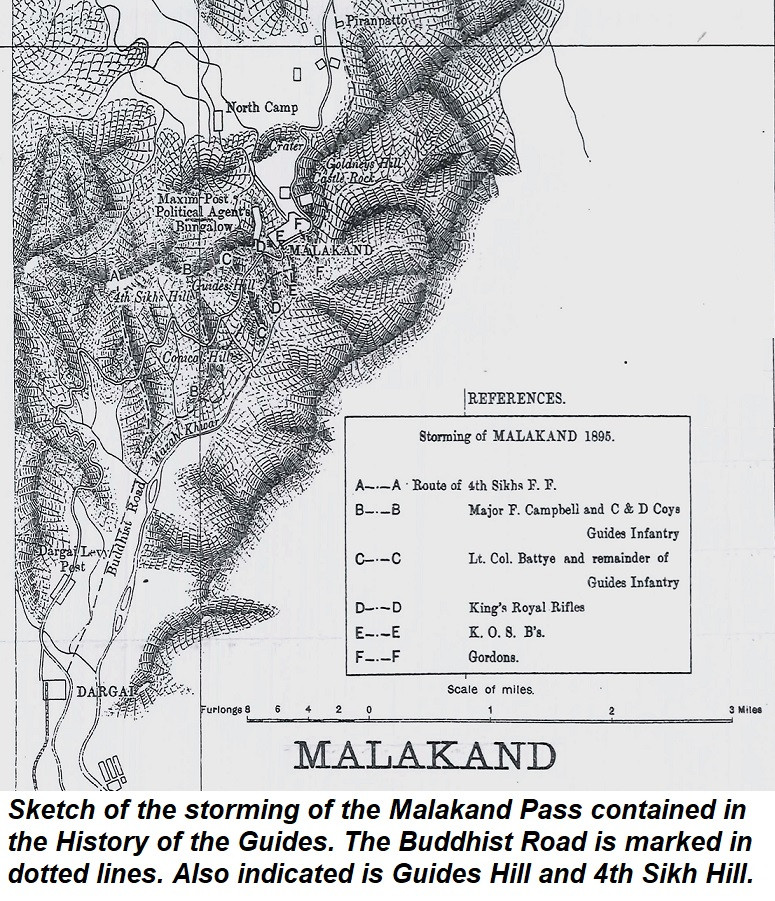

With funds from a UK-based charity, I am restoring a cemetery at the top of the Malakand Pass. It contains graves of officers and soldiers who died during the Great Frontier Uprising of 1897. During my research, I consulted the history of the Malakand Field Force written by Sir Winston Churchill who accompanied this army as a journalist, and found a map of the British encampment ahead of the pass. East of the camp are marked two tracks leading down to Dargai with the following short description – “Two roads give access to the Malakand camp, from the plain of Khar. At one point the Buddhist Road, the higher of the two, passes through a narrow defile then turns a sharp corner.” At this narrow defile a small force of twenty Sikh soldiers led by a British officer held over 1000 tribesmen as they tried to attack the British encampment located on an area named the Buddhist Ridge.

Churchill was not the first to mention the Buddhist Road. Surgeon-Major L. A. Waddell who was with the Chitral Relief Force in 1895, re-visited the area of lower Swat two years later “………for the archaeological exploration of this ancient Buddhist land, formally called Udyana, and to secure sculptures for Government.” In a report published in The Academy on 19th Oct, 1895, he writes, “On the following day I ascended the Malakand Pass by the so-called ‘Buddhist road,’ as it has been lately named. It is an excellent ancient road, comparing favorably with the best mountain roads of the present day. It rises by an easy gradient, and several of its sections are cut deeply through the hard rock. This may have been on the line of march of Alexander the Great in his invasion of India, as Major Deane suggests. Be this as it may, it is very probable that Asoka, Kanishka, and the powerful kings who held this country, used this road and gave it its present shape.”

There is no evidence that Alexander or elements of his army used the Malakand Pass to descend into the valley of the River Kabul. It is likely that the Buddhist Road it did not exist then because mountain tribes avoided constructing thoroughfares that invited invaders. Most probably it developed during the large empires of the Mauryas and the Kushans that blossomed after Alexander’s invasion and encompassed this region. Buddhism was introduced into Swat in the reign of the Mauryan emperor Ashoka (ruled 286-232 BC) and some of the earliest stupas were built within the valley. Under the greatest Kushan king, Kanishka (ruled 127-150 CE), Swat became an important region for Buddhist art. Between these two great empires, an Indo-Parthian kingdom ruled the northwest region of the Indian subcontinent. The world-famous Buddhist monastery at Takht-i-Bhai established during the reign of the Indo-Parthian king Gondophares (20-46 CE), is only 40 km from the Malakand Pass and there would have been a steady flow of Monks, pilgrims, and travelers to and from Udyana, the name of the valley of Swat during that period. Udyana is the Sanskrit word for garden and orchard and the 4th-century Chinese pilgrim Fa-Hien and the 8th-century Korean monk Hye Cho entered it probably via the Buddhist Road.

Despite evidence of the existence of the Buddhist Road, I could not find any information on its alignment. Little did I realise it was on my bookshelf, in the first volume of the History of the Guides. My brother-in-law Brigadier Jafar Khan, Guides Cavalry possessed the original volumes and presented me with their photocopies nicely bound in leather and embossed. The Corps was part of the Chitral Relief Expedition that initially stormed the Malakand Pass. In his book Edge of Empire, Christian Tripodi writes that the Siege of Chitral was “…one of those instances of high drama, much like the siege of Mafeking during the Second Anglo-Boer War, that attracted a huge amount of attention throughout the Empire,” and the storming of the Malakand Pass was by far the most dramatic event of the campaign.

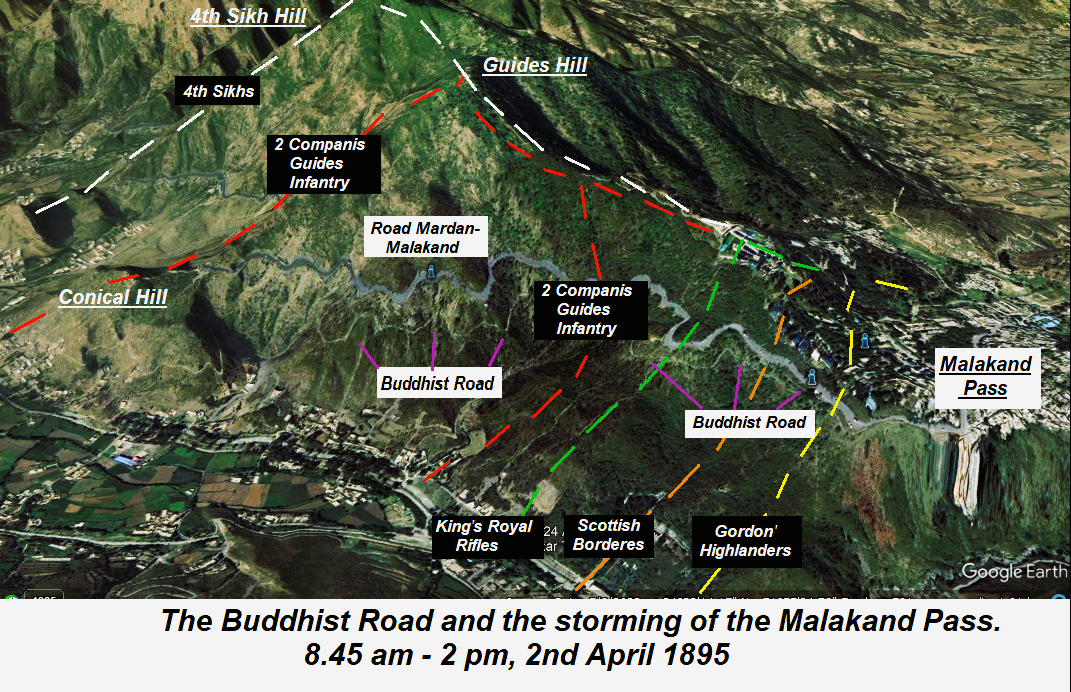

A division of three brigades of 15,000 fighting troops marched from Mardan on 2nd April 1895 and camped at Dargai for the night. The next morning the 2nd Brigade of four battalions set off to scale the pass led by an advance guard of a squadron of Guides Cavalry with two companies of Guides Infantry. When the advance guard neared the base of the pass, they came under strong fire from a sizable well-entrenched force of tribals.

The book ‘The Relief of Chitral’ by the two Younghusband brothers states that “The enemy's position extended along the crest of the pass, holding the heights on either flank, whilst a series of breastworks built of stone, each commanding the one below, were pushed down the main spurs. The position was of extraordinary strength, and one which in the hands of an organised enemy would have taken a week to capture. The enemy's numbers were afterwards found to be about 12,000, about half of whom were armed, whilst the remainder were occupied in carrying off the killed and wounded, fetching water, and bowling down huge rocks on the assaulting columns. The extent of the position may be put down at one and a half miles.”

Gen Low, the division commander decided to turn the opposing position by seizing the crest on the right flank and then launch a frontal attack on the pass. At 8.30AM The Guides Infantry and 4th Sikhs started to ascend three spurs to capture two features on the summit. They were expected accomplish this difficult ascent of 2000 feet in three hours, “…but so stern was the resistance, and so jagged and perpendicular the ascent”, that progress was slow in spite of the support of the 2.5 inch Screw Guns of the mountain batteries. Sensing that the Tribals were shaken by the threat to their right flank and the searching and accurate fire of the artillery, the general decided not to wait for the capture of the crest and launched the frontal attack.

The King's Own Scottish Borderers and the Gordon Highlanders were each directed up separate spurs. According to the Younghusbands, “It was a fine and stirring sight to see the splendid dash with which the two Scotch regiments took the hill. From valley to crest at this point the height varies from 1,000 to 1,500 feet and the slope looks for the most part almost perpendicular”. The chief reason for their success “……… was the wonderfully spirited manner in which the men rushed breastwork after breastwork, and arrived just beneath the final ridge before the enemy had time to realise that the assaulting columns were at their very feet.” Meanwhile, a fifth battalion, the 60th King’s Royal Rifles had been inserted between the two Scottish battalions. As it climbed up a reentrant, it chanced upon a wide and easy track on which it turned right and found themselves level with the leading companies of the King's Own Scottish Borderers. At this stage they did not realise that they had chanced upon the old Buddhist Road.

Taking a while to catch their breath and collect the stragglers, the three battalions answering to the call of the bugles, fixed bayonets, gave a loud shout and stormed the pass. By now the Guides infantry and 4th Sikhs had reached the crest and moved down along the ridgeline to the head of the pass. The tribes withdrew in a hurry having suffered 500 casualties. The British losses were 11 dead and 51 wounded. The admirable fire control by the infantry can be gauged by the fact that the average expenditure of ammunition was less than seven rounds per man. Two prominent peaks on the crest were named Guides Hill and 4th Sikhs Hill and are accordingly shown on the survey maps.

In recognition of the bravery of the Pathan, the Younghusbands wrote that, “…it is difficult to speak too highly, and individual cases were conspicuous. One leader, carrying a large red and white banner, called on his men to charge the Scottish Borderers when they were half way up the hill. The charge was made, but all his followers gradually fell, till the leader alone was left. Nothing daunted he held steadily on, now and again falling, heavily hit, but up and on again without a moment's delay, till at last he was shot dead close to the British line”. They also describe a Pathan drummer who with great courage stood on the roof of a hut to vigorously beat his drum. He was repeatedly shot and would again be up after dressing his wounds. The final bullet pierced his heart.

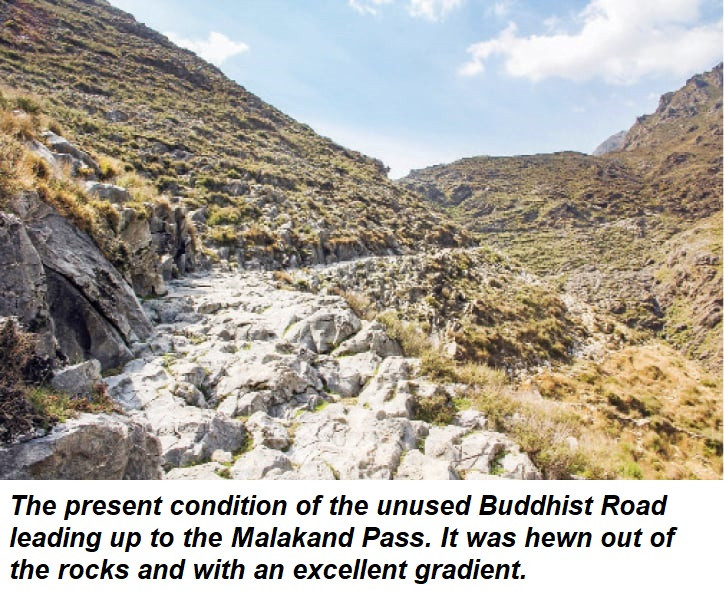

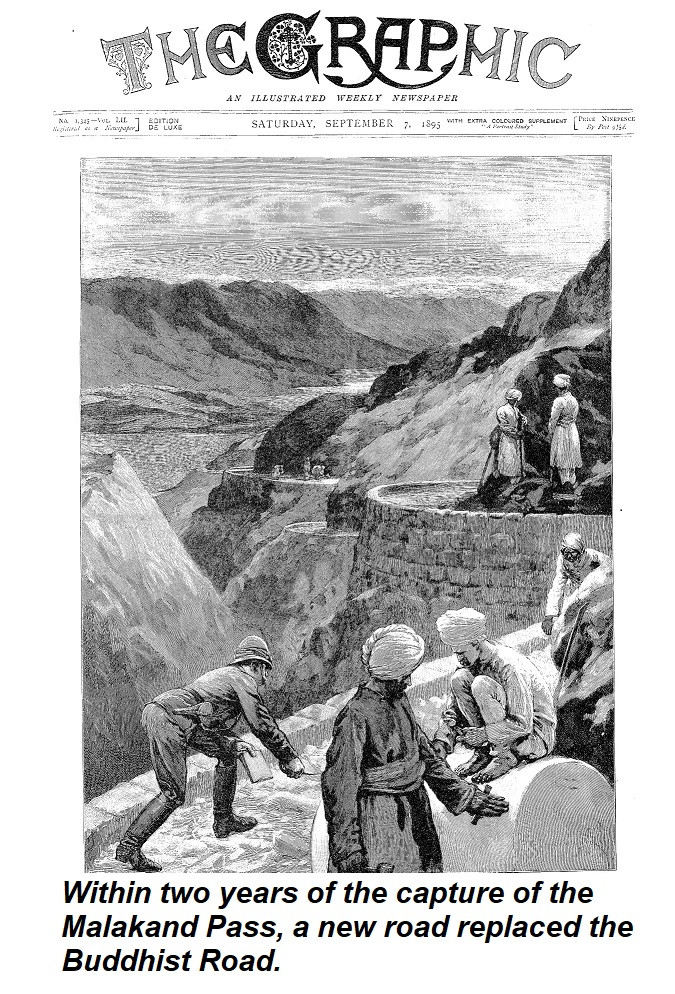

The next morning the supply officers commenced with the arduous task of moving the ammunition and stores of the leading brigades. The only route that zigzagged steeply to the top of the pass was strewn with boulders and was being hastily improved by the Sappers & Miners. However, by the close of the day the heavily laden mules had delivered a relatively small number of stores. Then in the evening there occurred what the History of the Guides calls a small miracle. The report of the action of the King’s Royal Rifles submitted by the CO mentions a disused road that the battalion had followed from halfway up the pass. The staff found that the road had an easy gradient down to the logistic base at Dargai and every available man was immediately employed to improve it. The history of the Guides further records that the road was so well made that it took only two days to improve it into a camel road which was traversed by the cavalry, 26,000 transport animals and 16,000 followers. Strangely, such a fine road leading up to the Swat Valley lay buried in the dust of history and unused by the locals for hundreds of years. It is also strange that the Guides that had based itself close by in Mardan 50 years earlier was unaware that a track with a fine gradient led up to the pass.

Within two years the British constructed a new cart road up to the pass and it seemed to me that that alignment of the Buddhist Road had been extinguished. However, to my luck, the History of the Guides has a very fine sketch of the day’s action by the brigade that shows the Buddhist Road running on the same side of the mountain as the present metaled road. It did not take me long to locate it on Google Earth as a clear track running 200-300 feet below and road. Having done all this research and confirmed the existence of the Buddhist Road I called a local who has been helping us with the restoration of the cemetery and he not only knew about the Buddhist Road, he also sent me some excellent pictures. It would be wonderful if the Buddhist Road is restored and would serve as an excellent attraction for historians, tourists, hikers and bicycling enthusiast.

Bibliography:

The Relief of Chitral by Sir Francis Edward Younghusband and G. J. Younghusband.

The Story of the Malakand Field Force by Sir Winston S. Churchill

History of the Guides 1846-1922. Printed by Gale & Polders, UK.

The Buddhist Road by Llewelyn Morgan

Syed Ali Hamid is a retired Pakistan Army major general and a military historian. He can be contacted at syedali4955@gmail.com

All facts and information are the responsibility of the writer