"Phatak meri chalni, phatak mere chaaj; nikal ri billi, tera hi raaj," I whispered under my breath, rinsing and repeating the mantra. How hard can a children's book truly be, I muttered to myself, as I walked blindsided into what would become one of the most enriching experiences I've come across to date.

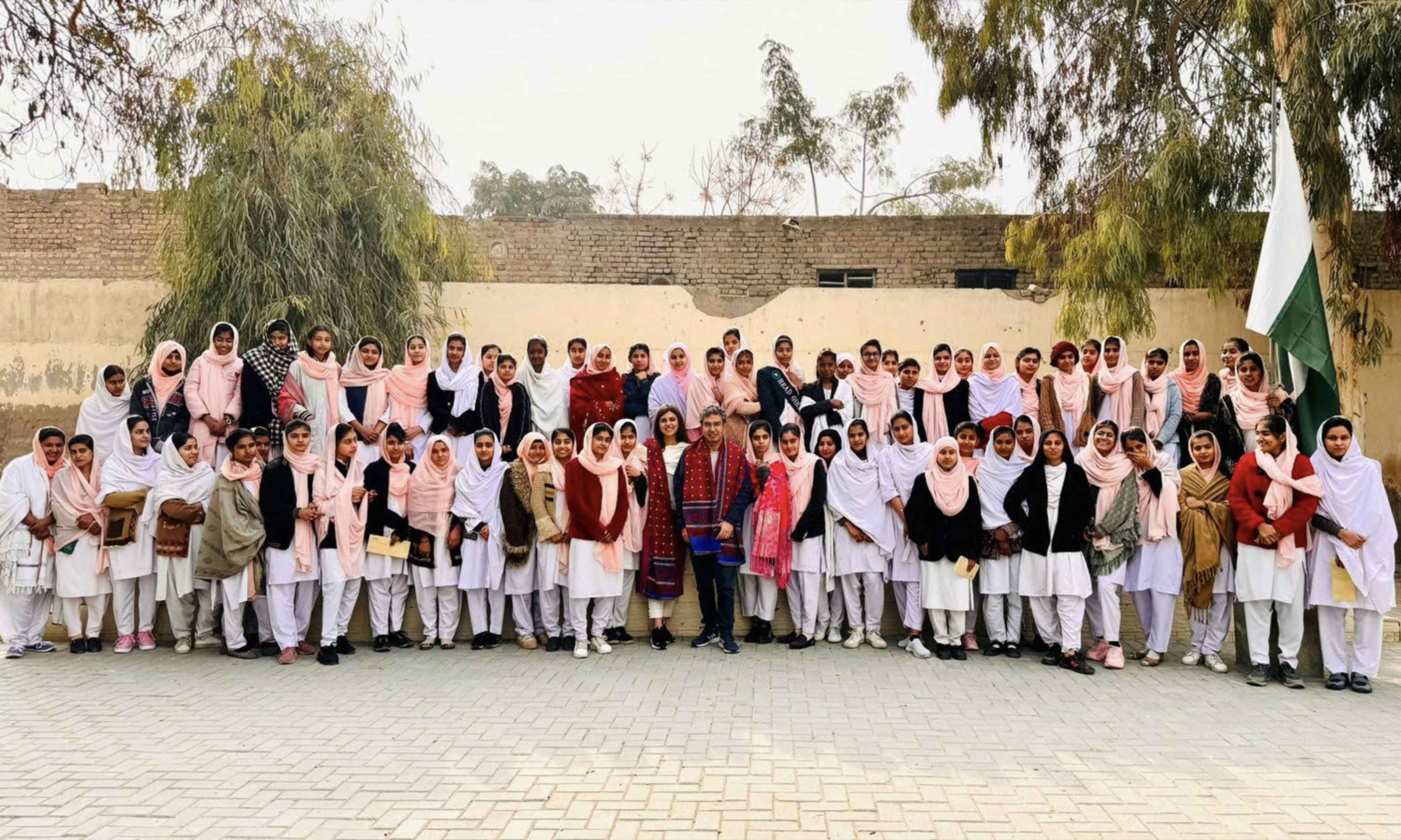

It was a cold January morning in Larkana as we headed on our way to visit four higher secondary girls' schools in the region. Unbeknownst what to expect and giddy with excitement, I settled my nerves and waited - from what I had been told by my roommate for the week, Rameesha Khan - to be wowed in the next hour. This was my first visit to the interior of Sindh alongside Musharraf Ali Farooqi, the Canadian-Pakistani author and CEO of StoryKit. He and his team had been working on a new project and this was the pilot chapter.

The plan was simple: we'd visit four government schools for girls in the Larkana region, including Dokri, Naudero and Baqrani. The idea was to understand the issues the teachers and students might face and help them cultivate their own stories, in their own words. The thought was to understand the hurdles they face, and the ambitions they carry, and ultimately help them nurture that dream into a wholesome creative story.

1710021562-7/unnamed-(8)1710021562-7.jpg)

The cold, crisp wind welcomed us to our first stop: Munawar Abad Girls Higher Secondary School in Larkana. There, Farooqi would demonstrate the tasks with the students of grades 9 and 10, and the rest of the team would follow suit at the next three schools. The students filled the classroom as Farooqi took the podium. "How are you all today?" he echoed in an electricity-sans room as he began narrating one of his stories to break the ice.

I was told the narration was imperative; it helped the students be relaxed and not think of us as their teachers but as friends. And that kind of confidence was of great importance if we were to work with the same group of students for the next five days. "You have to become their confidants," Farooqi said over tea the day before we headed to the schools. "They have to understand they're safe with you, they can talk to you and you'll be receptive to whatever they say." He furthered we might come across stories which might be difficult to read, but the whole idea is to highlight those accounts.

The backbenchers next to me giggled as Farooqi got into the rhythm and had the entire class responding to his calls. Once the story concluded, Farooqi then invited several students to come and share their renditions of the tale. The task for the day was simple enough: the students had to write their story the next day. On the second day, Farooqi inquired if the students had worked on the aforementioned assignment. Sure enough, 14-15 girls raised their hands.

1710021562-1/unnamed-(1)1710021562-1.jpg)

"I want to become a doctor when I grow up," Samina Lashari said while sharing her aspirations for the future. "My parents wish the same, but we are struggling due to our financial constraints." She went on, "My father's a labourer; every time he'd save some amount, it would be spent in one way or another. Once he had saved around Rs500,000 after much trouble. But then I became sick and he had to spend it on my course of treatment. Life isn't easy for us; we exert ourselves for basic needs. Therefore, when I grow up and complete medicine, I would like to open a clinic in our vicinity and treat patients free of cost."

"I want to become a fashion designer," a 10th grader Sidra Bhatti, shared with her class fellows. "But that wouldn't be realistic until I have some savings. To have some sum, I first plan on becoming a software engineer. I have the support of my family and we don't seem to face any major issues when it comes to our studies. If anything, my family is rather supportive of completing my education."

Humaira, on the other hand, was aiming for the stars! "I want to become a barrister when I grow up," she said, ecstatic, amid thunderous applause from her classmates. "I want to practice law and bring justice to those who had been wronged." But she didn't plan on stopping there. "My ultimate goal is to become the prime minister of Pakistan one day! I think pursuing law is the right first step."

1710021563-4/unnamed-(4)1710021563-4.jpg)

In Baqarani, the girls were more timid but supremely inspired by one of their teachers. Miss Nida Shah was, as many students told me, an absolute icon in the school and their town.

"I want to become a teacher like Miss Nida Shah," one of the 10 graders, Musarrat, told her friends. "But my aunt isn't particularly cheery about me continuing my education." Musarrat's father had passed away when she was five and her mother had remarried. She was living with her paternal uncle and aunt. "My aunt has had an accident which has left her disabled. But I manage my chores and studies well. I don't understand why she'd want to stop me from pursuing my dreams. I have challenged my aunt that I will complete my studies and fulfil my dreams."

Another student, Shahnaz Khatoon, wanted to become a doctor. "My brother supports me," she said. "We live in a small town, you know. There aren't proper institutes available for me to pursue my dreams, but my brother has promised that we'd shift to Larkana if need be, but he will help me fulfil all my dreams. We have many financial issues, but I am hopeful that we'll make it work."

1710021563-3/unnamed-(3)1710021563-3.jpg)

Shireen Gul labelled herself as the mischievous one. "I'd get off of a moving vehicle just for the fun of it!" she wrote in her story. But it was her maternal uncle's story that caught my attention further. "My mamoo was never in favour of his daughters continuing higher studies," she narrated, adding, "It's not shocking to have that kind of thinking here. But my cousin wanted to become a doctor. She was labelled as a rebel to fight for her rights. Isn't it laughable, miss? To be called disrespectful for something so basic - a right to education." Gul added this is where her aunt stepped in. "She took a remarkable stand for her daughters and threatened my uncle that she'd go over to the schools herself and get her daughters enrolled. That's when my uncle and his ego took a backseat, much criticism from his peers and neighbours."

Socio-cultural norms and expectations may contribute to financial challenges. Families, especially in conservative or traditional settings, may prioritize investing in boys' education over girls', perpetuating gender-based disparities in access to education. Gul furthered that by some miracle, her uncle later realised the importance of education and urged his daughters to fulfil their dreams. "Now, one of his daughters is a doctor. They used to own a bicycle before, but now they own a car! They also managed to buy a house in the city," she revealed. "Now, many men in our community are more inclined to let their daughters pursue education. My uncle's an avid advocate for it!"

In dire conditions

While the students had glittering dreams in their eyes, the conditions they had been forced to study in were quite dull. It took us, my partner Naveed Ahsan Godal and myself, a good fifteen minutes to even locate the Baqarani girls' higher secondary school. Unlike their counterpart, the boys' school that fashioned a huge sign to situate, the girls' school's main gate boasted several leafless branches. "We had a robbery at the school last year," Rasheeda Ajiro, Headmistress GGHSS Baqrani, told us over a hot plate of pakoras and fresh guavas. "They took the desks, the chairs, the fans. Since then, we have removed the sign for the school."

Upon inquiry, she furthered there was no electricity as well. "You see, it's cold right now, so it's not much of a bother. We had installed a solar panel, which helps run this one fan in my room and a bulb. But in summer, it's nearly impossible to survive in the heat but needs must." Didn't you complain about it, I asked. "Complain?" she laughed a hearty laugh. "No one cares if I am honest. We don't even have proper staff. The nearby villages, the city have strong political hold as you must have seen," she gestured, hinting towards the murals of several PPP politicians. "But they don't care what conditions these girls are studying under. I pay the clerk and the watchman out of my own pocket. We can't risk the robbery incident again."

She furthered, "I am sure it's the same in a lot of schools for girls you came across. The situation is troublesome, but what can we do? Whenever the elections are near, many candidates for provincial assembly visit us and make all sorts of false promises. Truth be told, I have stopped believing in them. They don't care and it couldn't be more obvious if they tried."

1710021563-5/unnamed-(5)1710021563-5.jpg)

The star teacher had similar woes to share. "There aren't many facilities provided to the girls here," she told us. "The financial issues are piling up and many of these students won't be able to continue their studies next year. That's just how it's always been." Shah, unlike her fellow teachers, held a certain charm within her students. "I treat them as my own children," she responded when asked her method of teaching. "This is a small town; all my students know my home address. If they come across an issue in their assignments, they know they can come over to my house after school hours and we'll work on it together."

Shah added how extra attention is needed for these students. "Many parents aren't literate; so these girls entirely depend on us to teach them the tricks and educate them," she said. She then revealed how she had bought land, not more than 100 yards, to construct a factory for her students. "I tell them to learn a skill alongside their regular curriculum," Shah commented. "It's important that they know how to stitch, how to cook. My lifelong dream is to open a workplace for these girls, so they can land a job and become financially stable. I am trying to work out the details of starting a factory and I am optimistic I can do it in the long run."

In the Larkana district, there are 176 government schools with an enrolment of 99,664 students. Out of the said number, 57,500 are male students while the number of female students is 42,164. "We're trying to do as much as we can," Sanaullah Aghani, Deputy Director of Education for Larkana district, conversed over lunch on our last day. "These girls are met with tiring conditions, the financial insecurity is prevalent, and hence we don't see much change."

The shortlisting

Out of over 200 students in the four schools we visited and worked with, we narrowed the shortlisted stories to 23 girls. They were awarded a monetary amount of Rs5000. If their stories are shortlisted further for publishing, they'd be awarded another monetary sum.

The project helped students develop skills coherently to tell their tales. One of the positive outcomes was they found their support system among their class fellows and friends, who lauded them, resulting in them becoming a close-knit group. Even after studying together for several years, many were unaware of the issues their close allies faced. "You can share anything you'd like with us," Pireh, a student from Munawar Abad, told her classmate, Samina, teary-eyed on our parting day. "You can trust us with your hurdles and we promise to help you and support you in any way we can."

1710021563-3/unnamed-(3)1710021563-3.jpg)

Moving forward

A UNICEF report says an estimated 22.8 million children aged 5-16 are out of school. The same census reported that disparities based on gender, socio-economic status, and geography are significant; in Sindh, 52% of the poorest children (58% girls) are out of school while in Balochistan, 78% of girls are out of school. Gender-wise, boys outnumber girls at every stage of education, the aforementioned report read.

"I'm not sure if I'd be allowed to continue after 10th grade," a student, who wished to stay anonymous, told me on our last day in Munawar Abad. Handing me a note, scribbled on an unevenly torn paper, she wrote a plea instead of her story. "Help me," it read. Several factors become focal points when we talk about the pertaining issues faced by girls while pursuing education. In some areas, particularly in rural regions, there may be limited access to educational institutions for girls. This lack of nearby schools can contribute to financial challenges, as families may need to consider additional expenses for transportation or boarding facilities.

Even when girls have access to schools, the cost of educational resources such as textbooks, uniforms, and stationery can pose financial burdens on families. In cases where multiple girls in a family are attending school, the cumulative expenses can become challenging. It's imperative to find new ways of supporting girls and their families to continue with their education.

As I returned to the fast-paced life of this metropolis, the silent note the student handed me over in Larkana still haunts me. The students, the girls and their dreams and ambitions hold similar importance as one studying in the top-notch private institute in the city. Their financial restraints and familial hurdles shouldn't be a reason enough for them to give up on their aims. There has to be a better way; we have to find a better way.