In 1801 the Lahore Fort witnessed the investiture of Ranjit Singh as Maharaja of an empire that he established and ruled till his death in 1839. These 38 years witnessed the evolution of the Sikh Army from a semi-feudal force to an efficient fighting machine that would have held its own against the best European armies. It not only drove the Afghans out of the Peshawar Valley, but it was by far also the most potent force faced by the East India Company.

Following the death of Ranjit Singh, the Khalsa Fauj [army] that he had raised, organised, and equipped, acquitted itself commendably in the two Anglo-Sikh Wars. Credit for the performance of the Khalsa Fauj to a great extent goes to its artillery. The gunners and their cannons were the legacy of the Maharaja who built it to an unprecedented level of efficiency with a genius that no other Indian ruler could match except probably Tipu Sultan. Tipu is recognised as the father of rocket artillery.

Four years after his investiture, Ranjit Singh began modernising his army by raising regular units, which included deserters/renegades from the army of the East India Company. They were lured into his service by higher wages and better opportunities. Around 1805, Dhaunkal Singh deserted from the Company’s Bengal Army and served Ranjit Singh with distinction. Promoted to the rank of colonel he commanded a regiment largely made up of other deserters from the army of the East India Company. Ranjeet Singh prescribed the most exacting standards of efficiency in march, maneuver, and marksmanship and spent three to four hours a day with the troops. Seldom did a day go by when he did not reward a gunner or a cavalier for good performance.

Before Ranjit Singh, troops of the Khalsa were mainly irregular cavalry fighting a guerilla war. Under his watchful eye (he was blind in the other) and encouragement, the army was trained and organised into a balanced force with the infantry and artillery gaining in importance. Raising a disciplined infantry was a gradual process because the Sikhs did not consider it honorable to fight dismounted. When the Maharaja introduced a system of drill across his army, the Akalis objected and called it Raqas-e-Louloan [Dance of Fools]. However, by the time of his death, the infantry had become the preferred service in the army.

The Sikh army and its artillery had been in action even before the Maharaja recruited European mercenaries in larger numbers. It had demonstrated its effectiveness and capability in battles with the Pathans and the Afghans on the Frontier. During the Sikh-Afghan Wars Ranjit Singh’s army made effective use of artillery at the battle of Attock (1813) and Multan (1818), as well as at Shopian (1819) during the campaign to wrest Kashmir from the Durranis. In all three battles, Ranjit Singh’s army was victorious. However, the Sikh army came into its own after the entry of European mercenaries from France, Spain, Hungary, Russia, Italy, and Greece as well as India. The total number is uncertain and figures vary between 32 and 100. Ranjit Singh wasn’t the first Indian ruler to recruit European mercenaries. Peshwa Balaji Baji Rao had given command of part of his artillery to a Portuguese who had several European artillerymen under him, and Mahadaji Shinde (1730-1794) the ruler of Gwalior recruited a French count to organise his artillery. Interestingly, when rulers could not recruit Europeans, they sought the services of Muslims as they had more experience in this area than other Indian nationalities.

After Napoleon’s defeat, Abbas Mirza the Qajar Crown Prince, an early moderniser of the Persian Army, hired several French and Italian mercenaries. However, British officers were also present in the Persian Army and their hostility and intrigues drove out the French some of whom travelled eastwards to the Punjab and sought employment with the Sikh Army. Three French officers gained prominence. Jean-Baptiste Ventura was employed in 1822 to train the infantry, and Jean-Francois Allard who was hired the same year, trained the cavalry. Five years later, the services of Claude Auguste Court were acquired in 1827 to organise and train the artillery. These officers were given the rank of Colonel, the highest rank in the Punjab Army at the time but all were subsequently promoted to generals.

Court organised the artillery, initiated rigorous training for the gunners, and elevated their efficacy to match that of European artillery standards. Discipline and pride forge courageous soldiers, exemplified by the gunners of the Sikh Artillery during the Battle of Gurat — the final clash between the forces of the EIC and the Khalsa Fauj. In his monumental work of the two Anglo-Sikh Wars, Amarpal Singh recorded a remarkable incident from the annals of a British battalion. As they pressed forward toward the Sikh lines, only one gun from a battery of eight continued firing steadily. However, the gunners serving it were gradually killed or wounded “… until at last only one fine old Sikh Artillerymen was left. Single-handed, he persisted... He fired several rounds on our advancing line, himself the target for shot, shell, and musketry.” Finally, his gun jammed and, “… he turned towards our advancing force, made a profound salaam, and then walked quietly away as if he was on his own parade ground.”

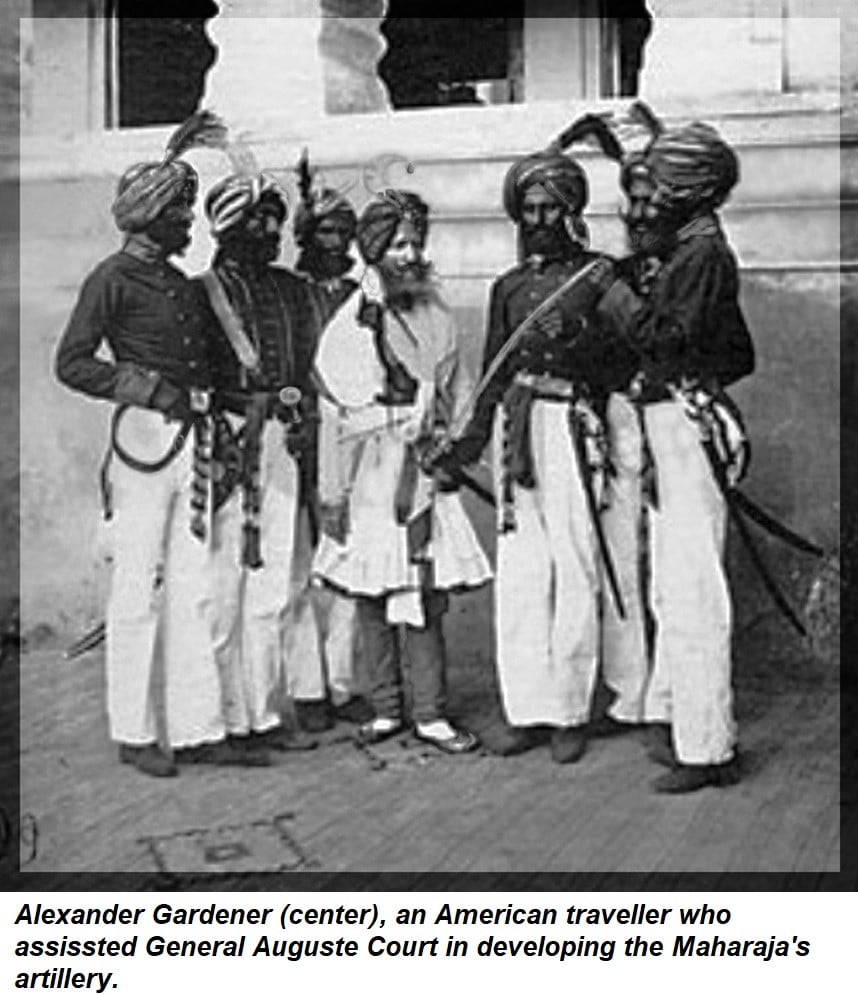

Five years after the Maharaja employed Court, an American adventurer, Colonel Alexander Gardner, joined him. Gardner was assigned the responsibility of organising and training the crews of the Topkhana-i-Khas, which was integral to the elite brigade of the army. As the Topkhana [artillery] expanded to incorporate various types of guns and carriages, it underwent several reorganisations and was classified into four distinct categories. There was the Topkhana-i-Feeli with the heavy cannons towed by elephants; Topkhana-i-Gavi consisted of medium cannons pulled by oxen; Topkhana-i-Shutri consisted of those guns which were pulled by camels; and Topkhana-i-Aspi consisted of light guns pulled by horses. The entire Topkhana (artillery) was organised into Deras (batteries), each of 10 guns and 250 gunners. A Dera was further organised into five sections, each commanded by a Jamadar with two guns and 8 to 10 gunners.

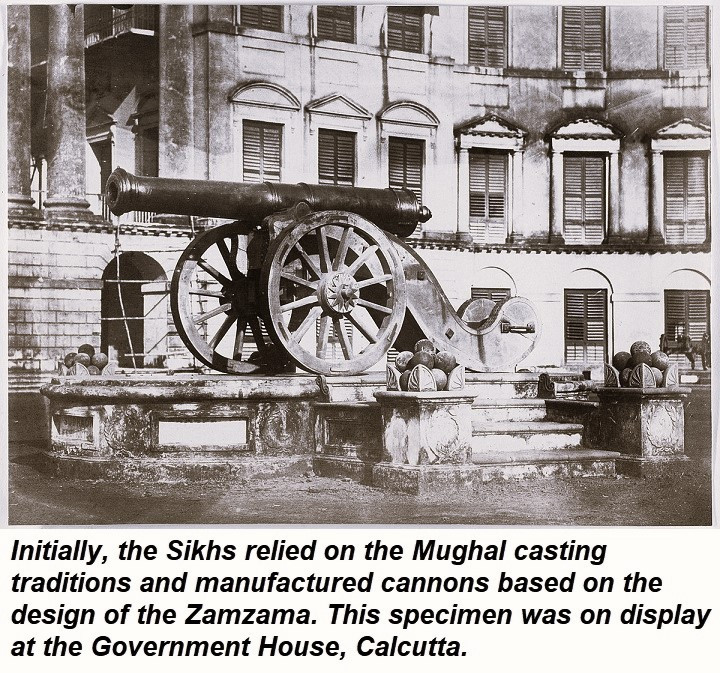

The most lethal part of the Sikh artillery were the guns manufactured at the Maharaja’s foundries at Lahore and their firepower made the Khalsa Army into a formidable force. At the commencement of the Maharaja’s reign, the Sikh Army had around 35 artillery pieces of varying design and quality. However, in 1807 he was seized with the idea of manufacturing cannons and established his first workshop for casting the barrels. Initially, the Sikh Army relied on the Mughal casting traditions already existing in the Punjab and produced large cannons based on the design of the Zamzama, which was cast in Lahore in 1760. Made of Bronze with a total length of 7.5 feet, it had a bore of 4.75 inches and the projectile weighed 8.33 pounds. One museum piece has been dated as late as 1825. The barrel is decorated in the Mughal style with palmette borders and a vase and flowers motif. The button is decorated with a lotus flower and dolphins in the shape of makara (mythical water demons); motifs widely used in Indian art. Meanwhile, the Sikh foundries also started manufacturing mortars.

Throughout his reign, the Maharaja ensured that his engineers had access to the ordnance factories of the East India Company and their patterns. The army recruited Purbia Muslims from Oudh who were slipped into the British ordnance factories to train as mistris (engineers) and returned with the skills needed for manufacturing ordinance. The closest equivalent was based on the “Blomfield” cannon, the heaviest type of artillery used by the British Army at Waterloo. It was a brass 9-pounder that was a foot shorter and weighed almost 240 kg less. At some point in its service life, probably in the 1820s, the barrel was remounted by Sikh engineers on a Napoleonic-style split trail carriage. Split trails allowed for a wider base, which increased the stability and corresponding accuracy of the cannon. Concurrently aiming was improved by attaching a strap around the button connected to a capstan elevating screw.

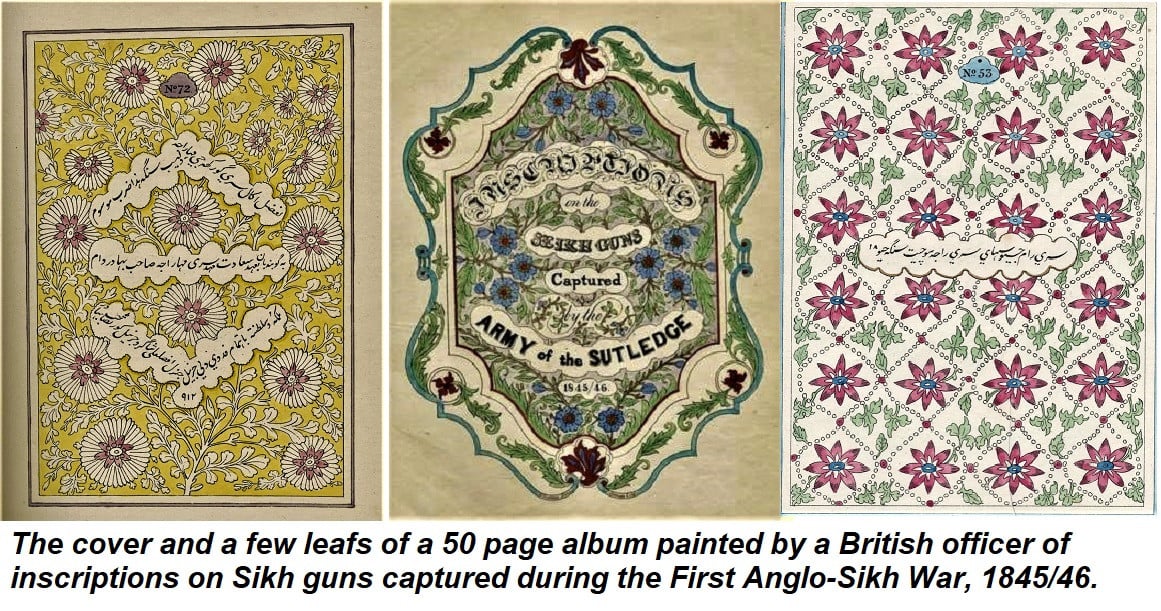

By the mid-1820s ornate barrels were being replaced by more streamlined types, which were both lighter and easier to cast. The mistris reverse-engineered the periodic gifts of cannons that the British made to the Maharaja as well as the designs that they brought from the factories of the EIC. One of the most successive models that was reverse-engineered was based on the design of the British Napoleonic-era 6-pounder cannon. It had a caliber of 3.25 inches, the length of the barrel was 5.5 feet, and the carriage was based on the Bengal artillery pattern introduced in 1823. The British christened it the Sutlej Gun because many were captured by the British at the Battle of Moodkee on the bank of the river Sutlej. Though the barrels were not ornate, some of the carriages were beautifully made of mahogany with pieced brass work and inlaid with brass, copper, steel, and inlaid with mother-of-pearl. Four guns attributed to the work of the prominent Sikh engineer, Lehna Singh Majithia, were captured at the Battle of Aliwal and were singled out for specific mention. They were most likely manufactured for the Fauj-i-Khas, or Royal Brigade, the elite brigade of the Sikh army. Commanded by his best French Officers, using French drill and imperial flags and eagles, it was also known as the French Brigade or the French Legion.

On the advice of his French generals, Ranjit Singh established the horse-drawn artillery. This accelerated the development of artillery to such a degree that by the late 1830s, his army had over 100 horse-drawn artillery pieces and could rival that of the Company in both quality and quantity. The Sikh Horse Artillery was equipped with the Sutlej Gun. A piece in a British museum clearly shows the exceptional technical and artistic expertise in the Sikh foundries and workshops.

One of the most informative articles I came across during my research was on the manufacture of cannons and ammunition during the reign of the Maharaja. It was written by Majid Sheikh whose ancestors worked in the ordinance factory in Amritsar before the defeat of the Sikh Army. According to Majid, Ranjit Singh employed educated Muslims from Lahore and nearby cities to establish karkhanas (foundries) for casting cannons and factories for manufacturing gunpowder and shots. The karkhanas were planned and operated by Claude Auguste Court and his deputy Mirza Afzal Khan, and both were immediately answerable to Sardar Lahina Singh Majithia. The largest ordnance factory was located near the Lahore ‘Idgah’, the subsequent location of Lady Willingdon Hospital, and a second where the Mughalpura Railway Workshop is presently located. Foundries for casting guns were also established at Shahdara outside Lahore, Nakodar, Sheikhupura, and Peshawar.

Working under Court for the manufacture of gunpowder and shot was Dr. Martin Honigberger, an Austrian traveler who became Ranjit Singh's court physician. The maharajah reasoned that Hakeems (doctors) would best know how to mix the barood masala (explosives) and Martin was made responsible for the gunpowder and shot manufacturing karkhanas at Mughalpura. He also established similar karkhanas at Amritsar, Multan, Shujaabad, and Layiah. Several hakeems from Bazaar Hakeema were hired to work and train other mixers at these factories. The raw material for the entire manufacturing chain came from deposits of copper and coal in the Salt Range and iron deposits in KPK.

It is estimated that at the time of the Maharaja's death in 1839, the Sikh army had 300 guns and anywhere up to 500 Zamburaks. The artillery continued to expand under the Khalsa Fauj but its management was no longer centralised and quality of cannons and ammunition surfed. Barrels were seldom ornate and bore only one Persian inscription. Their carriages were not of a uniform pattern and were rickety. They were also manufactured from unseasoned wood. The cannons fired a variety of ammunition but its quality also varied. The round shots were made from iron, brass, or zinc and crudely hammered into shape. Sometimes the shots were only of wood or stone. The effectiveness of the shells also suffered due to poor material. Despite these drawbacks during the two Anglo-Sikh Wars, the artillery performed exceptionally well.

Syed Ali Hamid is a retired Pakistan Army major general and a military historian. He can be contacted at syedali4955@gmail.com

All facts and information are the responsibility of the writer