When Sara and Ahmed learnt that their six-month-old child has thalassaemia major, and further tests revealed that they both were carriers of thalassaemia minor, they were shocked. All their lives, they were unaware of being thalassaemia carriers and were now shattered to know that they had unknowingly passed on the disease to their child, who would now have to undergo regular blood transfusions and treatment for the rest of his life.

Neither of them had ever experienced any health issues that would have revealed their status as carriers of thalassemia minor. However, now their child will suffer, and if they plan to have another child in the future, that child would also be at risk.

Pakistan, classified as a developing nation, grapples with a significant thalassemia burden, affecting 11% of its population. The country accounts for over half of thalassemia births in the Eastern Mediterranean Region, with approximately 5,000 affected children born annually. The average life expectancy for individuals with thalassemia major in Pakistan stands at a mere 10, a potential explanation for which could be attributed to inadequate quality of healthcare.

What is thalassaemia?

Thalassaemia is a blood disorder that affects the body’s ability to produce healthy red blood cells. The disorder also reduces haemoglobin production, which means that people with this condition will have fewer red blood cells to carry oxygen to their organs. It also causes excessive destruction of red blood cells, which leads to anaemia — a disorder in which the body doesn’t have enough normal and healthy red blood cells (RBC).

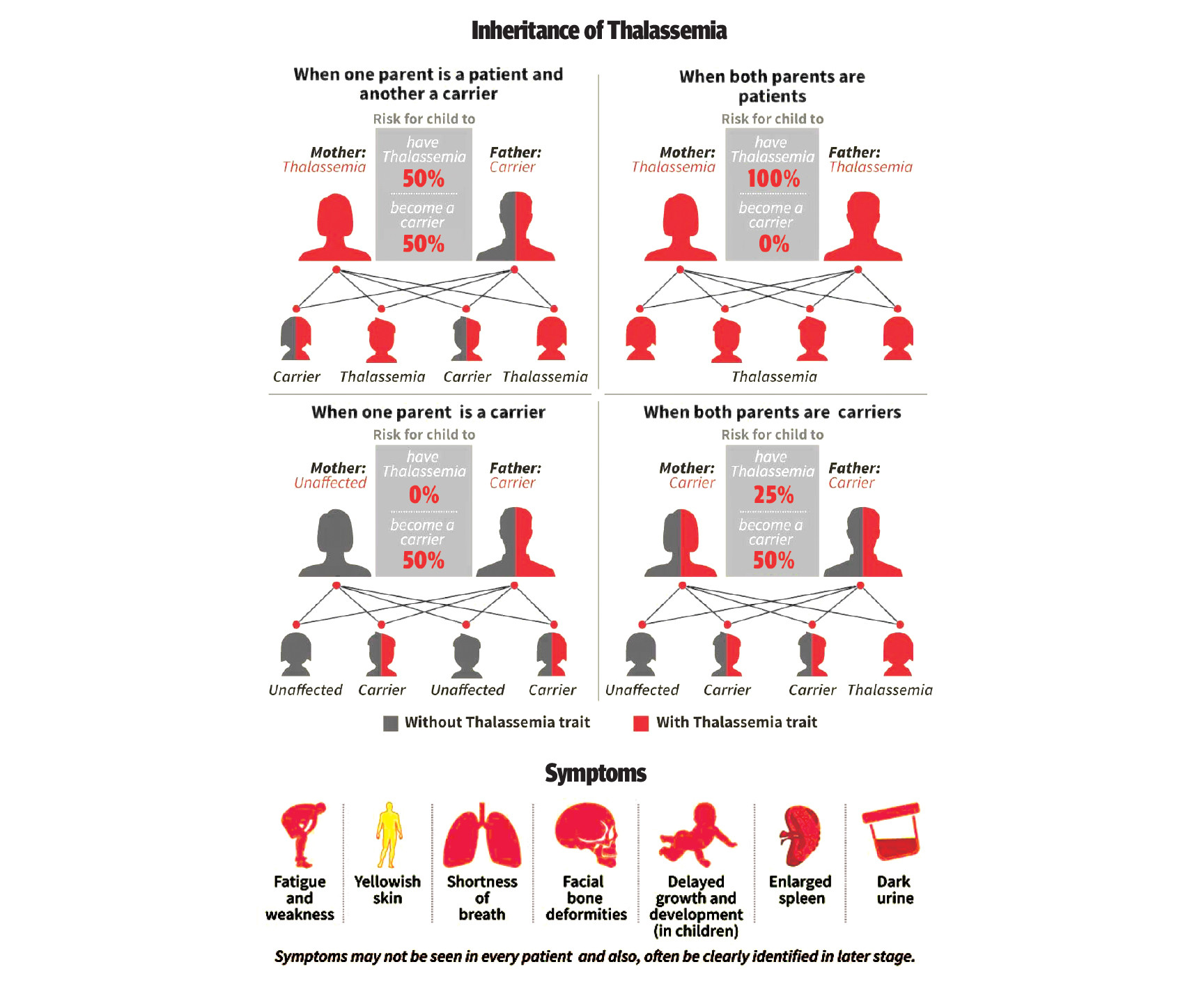

Thalassaemia is an inherited disorder, i.e. at least one of the parents is a carrier of the disease. It is caused by either a genetic mutation in a person’s DNA or a deletion of certain key genes. The mutations associated with the disease are passed on to the children from their parents.

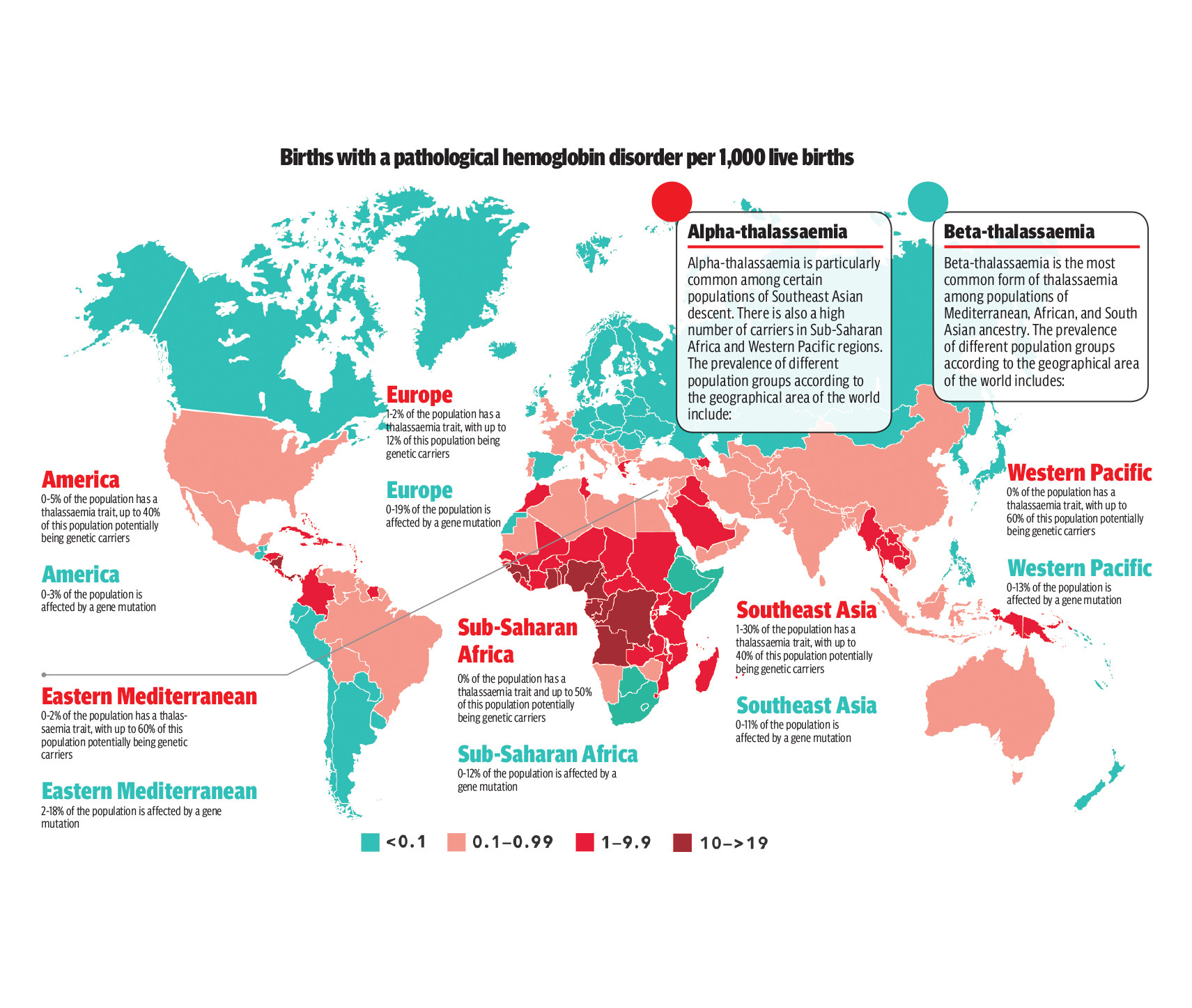

There are two main types of thalassaemia: alpha and beta. In alpha thalassaemia, at least one of the alpha globin genes has a mutation or abnormality. In beta thalassaemia, the beta globin genes are affected. Each of these two types have further subdivisions and can be mild, moderate, or serious, depending on how much haemoglobin one’s body makes.

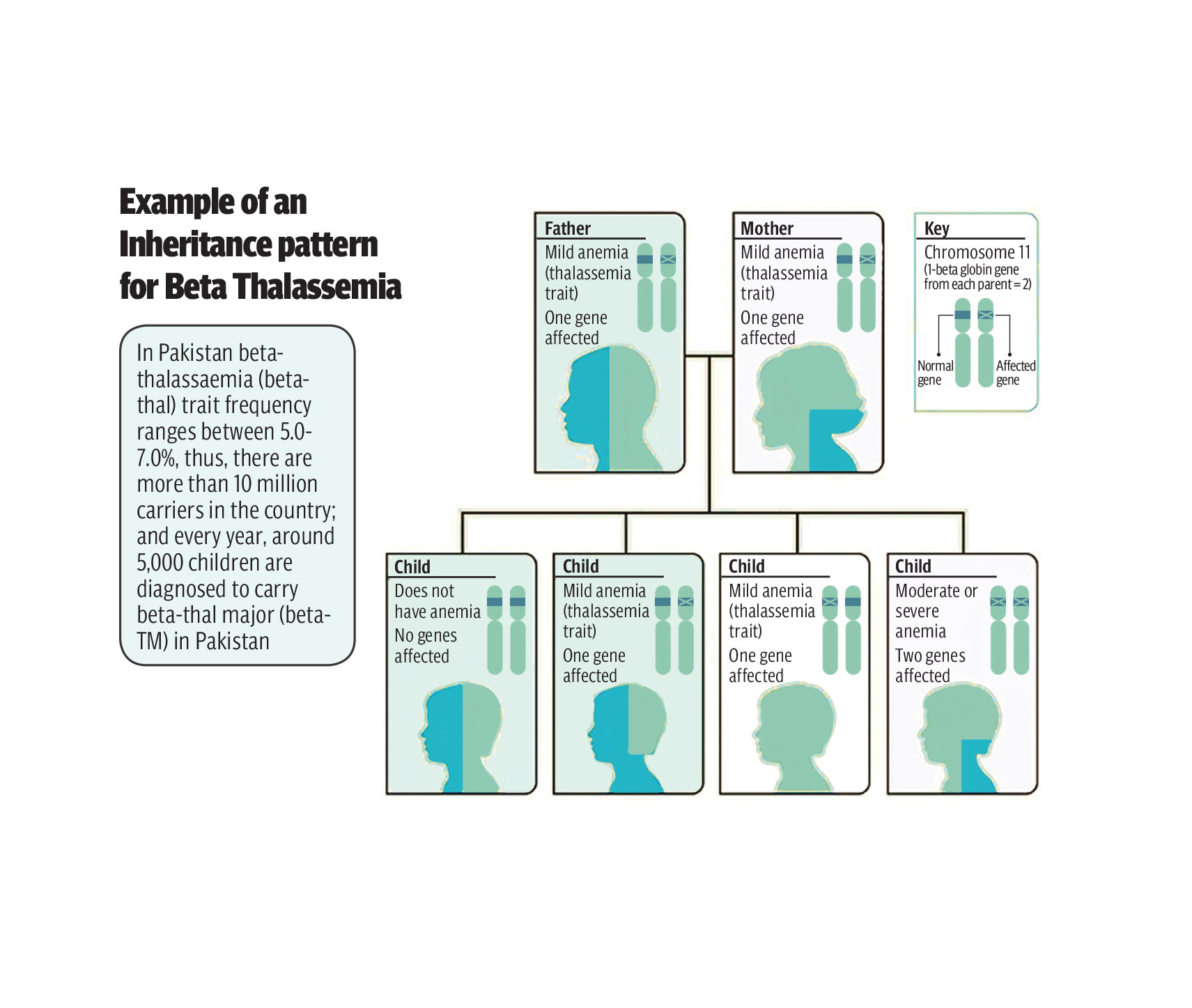

Of the two subtypes of beta thalassaemia, more common are thalassaemia minor and thalassaemia major. Thalassaemia minor is a less serious form of the disorder, while thalassaemia major is the most severe form. It develops when beta globin genes are missing—two genes, one from each parent, are inherited to make beta globin.

If only one of the parents is a carrier for thalassaemia, the child may have the less severe form, i.e. thalassaemia minor. He/she probably won’t have symptoms but will be a carrier, though some people with thalassaemia minor do develop minor symptoms, such as mild anaemia, but usually don’t need any treatment. However, if both the parents are thalassaemia carriers, each of their children has a 25 percent chance of inheriting a more serious form of the disease, i.e. thalassaemia major; a 50 per cent chance that the child will be a thalassaemia minor and a 25 per cent chance that everything will be normal.

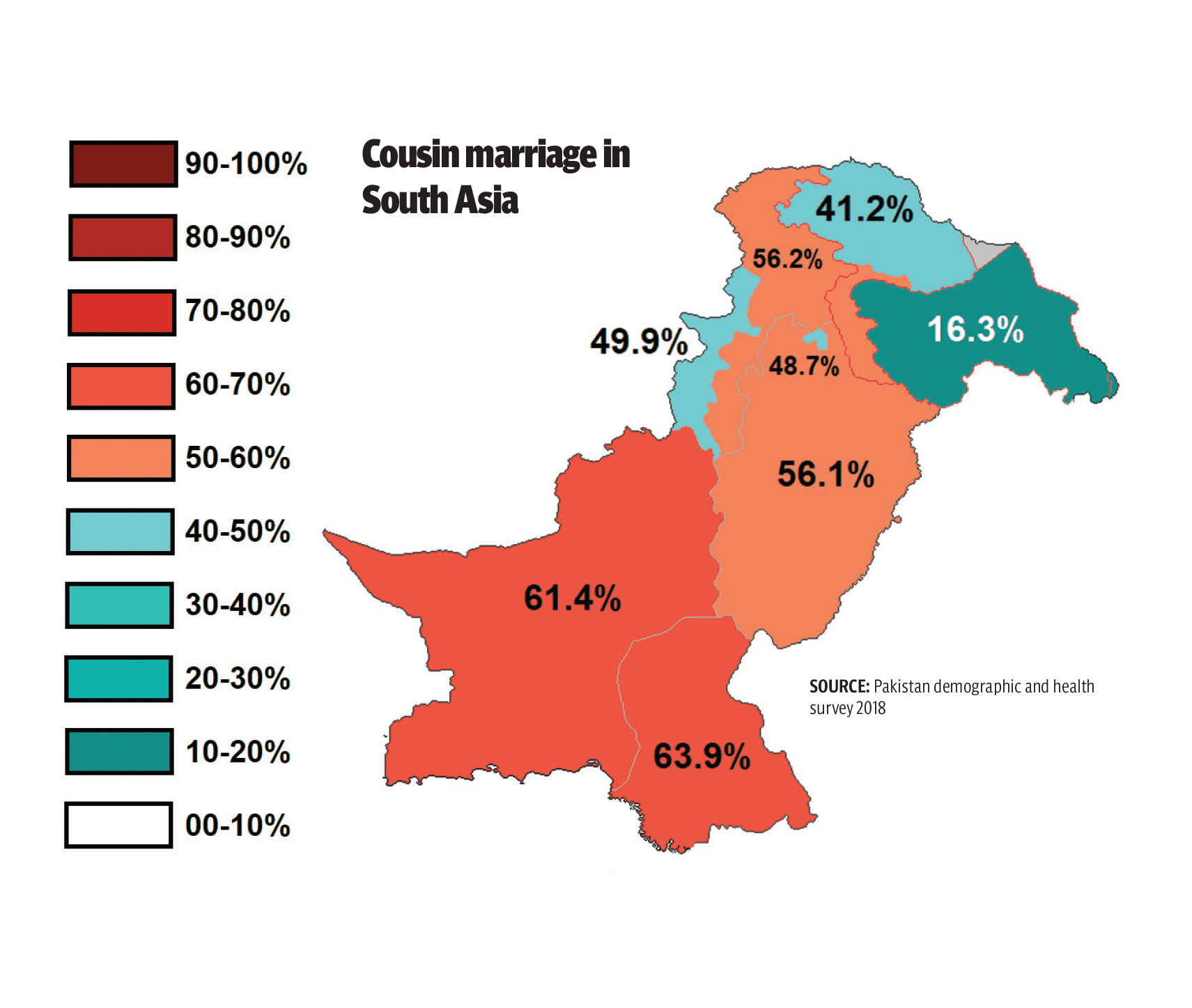

Marriages between blood relations

Ayesha Mehmood was diagnosed with thalassaemia when she was only six months old. Both her parents are thalassaemia minor carriers, while she has thalassaemia major. Her parents were first cousins. “My two elder brothers were also born with thalassaemia major. Unfortunately, in the mid-80s, there wasn’t much awareness about thalassaemia, and we three siblings were the first cases of thalassaemia major in our entire family.”

Cousin marriage is a major factor in producing children with thalassaemia, and it can be mitigated if potential spouses are screened for the disease.

Now 35 years old, Mehmood is the President of FAiTh (Fight Against Thalassaemia) a patients’ and parents’ society, a certified expert patient by Thalassaemia International Federation, representing Pakistan in Thalassaemia Advocacy Group and member Thalassaemia International Federation since 2009.

“There are few symptoms in thalassaemia minor and often the carriers are asymptomatic and can only be detected through blood tests,” says Dr Muhammad Rizwan, Associate Prof. Pathology, Deputy Director Baqai Institute of Haematology, Baqai Medical University, Karachi. “But thalassaemia major patients show early symptoms, and is usually diagnosed in the first year of life.”

Unfortunately, premarital diagnostic tests for thalassemia are often neglected, despite the existence of laws mandating such tests. Doctors cannot stress more that couples should undergo some important diagnostic tests before marriage, including a blood group test, Hb electrophoresis, hepatitis B and C virus tests, as well as HIV/AIDS diagnostic tests.

When to test

Anaemia is the major symptom; further symptoms include anaemia-related problems, loss of appetite, delayed growth because of not taking proper diet, bone deficiencies, shortness of breath, and frequent infections. If these symptoms are seen in a child, it is important to get tested for thalassaemia.

About 300 million people around the world have the ‘thalassaemia trait’, which puts them at risk of having children with some form of thalassaemia. Thalassaemia has a high prevalence in areas extending from the Mediterranean basin and parts of Africa, throughout the Middle East, the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia, and Melanesia in the Pacific Islands.

According to reports, there are approximately 10 million thalassaemia carriers in Pakistan and every year 5,000 babies are diagnosed to have thalassaemia major.

The current treatment for thalassaemia major primarily involves blood transfusions, though “the ideal treatment for thalassaemia major is bone marrow transplant, it is only suitable for children under 10 years of age. Also, it is quite expensive and needs a specialised centre, donor, etc. and because of the cost everyone cannot afford it,” says Dr Rizwan. “Haematology Society of Pakistan has been asking the government to subsidise it, though Dow University is doing some subsidised cases.”

Life expectancy

“It is unfortunate that life expectancy is quite low in thalassaemia patients, about 22–23 years in our country; it depends on the frequency of blood transfusion and iron chelation therapy,” says Dr Rizwan. “Since thalassaemia is a blood disorder, all organs are compromised. As blood transfusion is required at least twice a month there is a chance of iron overload which further affects all organs, leading to heart, liver, bone and joint problems.”

Major complications in people who have thalassaemia are usually caused by iron build-up in the blood (iron overload). Regular transfusions can cause iron build-up, or iron overload, which can damage organs and tissues and lead to potentially life-threatening complications. To prevent this, expensive iron chelation therapy is required to remove excess iron from their bodies.

“Blood is a sensitive product that must undergo thorough screening and testing before being transfused to patients,” adds Mehmood. “Improperly screened blood can lead to adverse reactions and potentially transmit diseases like hepatitis or HIV to the recipients.”

Challenges

“Unfortunately, in our country, voluntary blood donations are significantly lower as compared to the number of thalassaemia patients. This shortage of blood supply can make it challenging to arrange transfusions when needed. Besides arranging transfusions which is required on a regular basis, the patient faces many problems in their day-to-day lives,” Mehmood explains. “To lead a normal life, we must carefully manage our haemoglobin and iron levels. Failure to receive timely transfusions or medication can lead to complications and, in severe cases, even death.”

Day-to-day life is affected, as there is less physical activity due to anaemia and shortness of breath, etc. Mehmood recalls that as a child, dealing with the challenges of frequent transfusions often left her feeling both physically and emotionally drained. It was hard, especially when she had to miss her regular classes. “However, the unwavering support of my friends, family, and teachers was a constant source of strength during those tough times. Despite the hurdles, their encouragement and understanding made the journey a little easier to bear.”

The diet needed

Dr Rizwan recommends good balanced diet which should include meat, fruit, cereal, etc. but points out that since a lot of patients are from poor classes (though it is not a class-based disease and exists in all social strata) they cannot afford these and their well-being is affected. He also stresses on the importance of regular check-ups.

Pre-marital screening

Being a genetic disease prevention is the only way to curb its spread, otherwise more and more cases would continue to emerge. The best way is to take care that two thalassaemia minor carriers do not marry each other and to ensure that all couple who intend to marry should have pre-marital blood screening done.

Dr Rizwan says, “Screening before marriage should be made mandatory and entered on the nikkah nama. There are screening laws in the developed world and also in some Muslim countries such as Saudi Arabia, Qatar, UAE, etc. A bill to the effect was presented to our parliament too but could not be passed.”

Cyprus was among the first countries that implemented mandatory premarital testing for beta Thalassaemia in 1973. It was followed by several countries in the Middle East to include Iran (1997), Saudi Arabia (2004), and United Arab Emirates (2011).

In Pakistan, in 2016, a bill was tabled in the Senate with the purpose of checking inherited blood disorders and birth defects. Named The Premarital Blood Screening (Family Laws Amendment) Act 2016, it aimed to bring amendments to family laws to control the spread of HIV/AIDS, thalassaemia, hepatitis, and other communicable diseases by making pre-marital blood screening mandatory. Under the amended family laws, which include Muslim Marriage, Christian Marriage and Divorce Act and Parsi Marriage Act, a couple would have been bound to get their blood screened before marriage. The bill was quickly referred to the relevant committee for further deliberations, but unfortunately nothing came out of it.

Dr Rizwan is quite vocal about lack of awareness about the disease and its prevention, and strongly advocates premarital screening for thalassaemia. “Pakistan haematology society recommend that all couples should go through screening before marriage,” he says.

People who are anaemic and do not respond to iron treatment should also have their carrier status done. Laboratory tests for thalassaemia include a routine blood test known as a Complete Blood Count which includes measuring the level of haemoglobin and other parameters related to the number and volume of red blood cells.

To determine the presence of β-thalassaemia and confirm that the individual is a carrier of β –thalassaemia, a laboratory process known as haemoglobin electrophoresis, which enables quantitative measurement of haemoglobin is done. In most cases, the above tests are sufficient to determine whether an individual is a carrier or not. In some circumstances, genetic or DNA tests need to be carried out to confirm an individual’s status as a carrier.

“It is better if parents who have one child with thalassaemia major should not opt for another child and if they do conceive, they should go for prenatal screening,” says Dr Rizwan. “Nowadays, intrauterine sampling is possible after conception. If the foetus is thalassaemia major then it is recommended that it be aborted; if it is not major then the pregnancy could be continued with.”

It is recommended that couples who are aware that they are carriers of β-thalassaemia, should undergo prenatal diagnosis to prevent the birth of an affected child. The prenatal diagnosis method used in Pakistan is Chorionic Villus Sampling (CVS), though there are other tests too in other countries.

CVS can be done earlier in pregnancy (at 10 to 12 weeks) to see if the child is affected or not and allows the parents to make an earlier decision whether to continue or end the pregnancy.

Sara and Ahmed regret their lack of awareness as now they know that if they had been better aware their child wouldn’t have to suffer all his life. If they had known their status they wouldn’t have gotten married or would either not have conceived at all or gone for prenatal screening.

Raising awareness

FAiTh is a non-profit NGO that aims to create awareness among thalassaemia patients, their parents and the general public. It was founded by Mehmood’s parents to support patients through blood donation and financial assistance. In 2003, her late brother Salman created the first-ever website on thalassaemia in Pakistan, www.thalassaemia.com.pk, which gained international recognition. “He was a passionate advocate for premarital thalassaemia testing. Following his passing in 2009, I assumed leadership, and FAiTh now provides support to patients with free medicines, consultations, hospitalisation, rations, employment, education, etc.,” says Mehmood.

There is a need to create awareness about this disease because prevention seems to be the only way to prevention. There should be campaigns to create awareness. Dr Rizwan says that Pakistan haematology society has recommended that mobile messages be run in the same way as at present we have the cancer awareness, dengue awareness and other awareness messages on phone. If this is not possible on a regular basis, they can be run from May 1-10, i.e. around May 8 which is thalassaemia day.

Rizwana Naqvi is a freelance journalist and tweets @naqviriz; she can be reached at naqvi59rizwana@gmail.com

All facts and information are the sole responsibility of the writer