I decided to enroll in the Pakistan Armored Corps at the age of five as Sepahi Painda Khan. A few years later I was introduced to a tank. Our father took us to the 502 Workshop at Rawalpindi where there was a Sexton Self Propelled Gun waiting on the driving track. I took one look, didn’t like this growling monster and refused to climb on. I was ribbed all the way back home.

Ten years later my reaction was the opposite. It was March 1966 and Major (later Brigadier) Muhammad Ahmed SJ of Chawinda 1965 fame dropped in to meet my brother. He was heading for Nowshera where his regiment, the illustrious 25th Cavalry was firing at the AFV Ranges. He invited me to come and I jumped at the opportunity. For a teenager, it was a glorious three days with his regiment’s Pattons and if I had any doubts on joining the armored corps, they vanished in a cloud of fumes from the Continental V12 engine mixed with the odor of cordite from the 90 mm gun. It would be a good two and a half years later that I would come close to a tank again.

In the final year at the Military Academy, we were asked to select the arm or service we would like to join. My father was commissioned into 3rd Cavalry which is now part of the Indian Army but over a squadron strength of Punjabi Muslims from his regiment had transferred to 11th Cavalry at Independence. I therefore had a ‘claim’ on 11th Cavalry and when the postings were announced that is what I got. Two of my companions were posted to 26th Cavalry and to my surprise I came to know that our term commander, Major Akram Hussain Sayed had been promoted and assigned to raise this new regiment.

Like many of my fellow cadets, I admired Akram for any number of reasons. When he was not looking at you with a stern face and a cocked eyebrow, he had an impish smile that was very appealing. He drove his VW Beatle like it was a Porsche and played polo with equal vigor. I also knew that he was fond of me. In fact, at the beginning of the final term, I was a Cadet Sergeant but when my friend Munir Hafeez was demoted from the appointment of Battalion Sergeant Major, it was on Akram’s strong recommendation that I replaced Munir. With this confidence, I intercepted him as he was walking back to his office after the postings were announced.

“Sir! You are raising a new regiment?” I enquired.

“Yes Ali” he replied.

“Sir,” I said. “I would like to come with you”.

Fifty years have passed but I still remember his words. “Ali. I would love to have you but you have already been posted to a very old regiment.” With all the naivety of two years of cadet service, I pleaded “Sir. Please get my posting order changed.” He was a hard taskmaster but with whatever little that I knew at the age of 19 years, my instincts told me that he was the sort of commanding officer that would be good for me.

When my joining time ended on 14th November 1968, I headed for Jhelum where the regiment was in the process of being raised. I had no idea what to expect but, in some ways, it couldn’t have been worse. The regiment had one office block and a single barrack for the 45 JCOs, NCOs, and soldiers who were the first to arrive from different regiments. There was also a cookhouse, three Jeep M38A1s, and four M34 Reo trucks whose engines smoked like a steam engine – but no tanks! In an established regiment, young officers are harnessed from the first day, assigned a tank troop, and put through a rigorous program of instructions on everything related to the tank. But since our regiment had no tanks and not enough men to even form one squadron, Colonel Akram very sensibly sent all the subalterns on leave for 15 days.

By the time we got back, the regiment had an exceedingly smart and stern adjutant, Captain Mansoor Irfani. A week later the subalterns were driven to join the Guides which was in the midst of a field exercise near the firing ranges at Tilla. The Guides was one of the oldest regiments in the Armored Corps and we were feeling a bit intimidated because the officers from the senior regiments can be snobbish. However, I was fortunate to be taken under the wing by Faheem Ataullah Jan who was commanding a squadron. I slept on the ground in the canvas shelter of Faheem’s tank crew alongside their M48 tank. That night for the first time I experienced the smell of petrol and warmth from the engine of the tank mixed with the body and other unmentionable odors from the tank crew.

Back to the regiment after a few days with the Guides, we were attached to an independent squadron of AMX-13s that was part of our division. It was a light tank with a quiet engine and a powerful 76mm high-velocity gun that the Israelis mounted on their Super Sherman. They had been captured from the Indian 20th Lancers during the 1965 War in the Chhamb Sector nearby after they had inflicted some serious damage to the M48s of 11th Cavalry. Befittingly the AMX-13s were now manned by officers and crews of 11th Cavalry from Kharian and the winter of 1968 that we spent with this squadron was idyllic.

When we arrived back in the regiment three months later, a lot had changed for the better. The unit had been allocated a full set of barracks in the Auchinleck Lines. The bulk of the manpower for 26th Cavalry had arrived which included 180 all-ranks from the Guides and they proved to be the backbone of the regiments. Orders had been received to take over the Shermans from 27th Cavalry at Kharian.

Chacha Sherman was what in modern-day jargon could be described as a user-friendly machine. It had been designed and fielded during the Second World War by the Americans to be operated by conscript soldiers with 3 months of training in boot camp. Though outclassed by the larger guns that most of the Indian tanks were now equipped with, its 76 mm High-Velocity gun still carried an effective punch. It had a decisive edge with a stowage capacity of 78 main gun rounds which was twice more than tanks with larger caliber guns. Its weakness was its relatively thin armor plating and an engine that had been overhauled multiple times since we received them from the Americans in 1954.

It was a great day for the regiment when the tanks were transported to Jhelum and arrayed in the garages for the first time. The WWII vintage Shermans were showing their age but we never questioned the wisdom of our army in issuing them to our regiment in spite of the fact that the Indian Army was converting en-mass to more superior tanks like the British Vickers Vijayanta and the Soviet T-54s. As time went by, we became very proud of the fact that we could keep such an old piece of military hardware in combat condition.

Colonel Akram was a dynamic and experienced officer who had commanded a squadron of 15th Lancers in Khem Karan during the 1965 War. One morning while Akram was visiting the tank park, the Colonel Staff from the division headquarters rang wanting to talk to the CO. I sent my office runner to inform the CO but he returned in a few minutes to tell me that Akram had driven off in his jeep. I had no idea where he had gone or for how long and when I informed the Colonel Staff, he rebuked me. “What sort of Adjutant are you who doesn't know where his CO is?”

I was still smarting from the remark by the Colonel Staff when Akram returned four hours later. He looked at my expression and asked what was wrong. I told him that I had been ticked off by the Colonel Staff for no fault of mine. He walked into his office and dialed the Colonel Staff who was a full colonel and senior to him in rank. There were a couple of minutes of silence interspersed with ‘Sir’ and ‘Yes sir’. When the Colonel Staff had said what he had to, I heard Akram say something that endeared me to him. “Now sir… The adjutant is my staff officer. If he does something wrong, I am the person to tick him off.” It was one of my early lessons in leadership.

Col Akram had been commissioned in Probyn Horse and had served under General Gul Hassan, one of the pioneers of armor training. With this grooming, he trained the regiment hard. He would test every Daffadar who was aspiring to be a JCO while the regiment was out in the field. It was a small test exercise in which the Daffadar commanded a tank during a simulated battle run of 5-6 km. Targets were depicted by waving a large flag 1000 – 1200 meters ahead of the tank; blue for a recoilless rifle and red for a tank.

Obviously, the Daffadar was tense. The CO standing behind him on the hull plate behind the turret, connected to the wireless circuit within the tank, was listening to every transmission the tank commander made within the crew and to his troop leader. The tank had advanced a few hundred meters when a red flag appeared next to a small house. The tank commander responded correctly. “Driver position” he shouted into his microphone and as the tank stopped behind the cover of an embankment, he looked through his binoculars and gave the orders to the loader and gunner as per textbook. Before he could shout “Fire”, the CO tapped him on the shoulder and asked “Tumhe kia nazar aya hai [What have you seen]?’ The tank commander was still looking through his binoculars with great concentration. They had been recently issued to the regiment and were of a superior quality with rubber covering its body and caps to protect the lenses. “Saab! 1200 gaz per aik makan. Us ke left kinare se 300 gaz per darakht ke neeche dushaman ki tank. [Sir! At 1200 yards there is a hut. 300 yards from its left corner and under a tree is an enemy tank.]” Akram gave the tank commander a hard whack with his stick on his helmet and said, “Bloody Fool! Tumhare doorbeen ke lens per flap lage hain aur un ke ander se tumhe dusman ke tank nazar aati hai? [The flaps are still covering the lenses of your binoculars and through them, you see an enemy tank?”] That night in the field mess there was much laughter amongst the young subalterns after the CO had gone to bed.

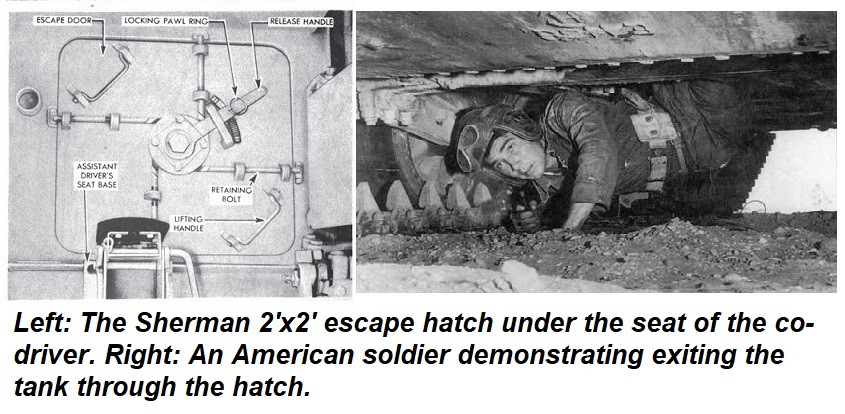

We subalterns had a chip on our shoulder more so than most young armor officers because ours was the only tank regiment in Jhelum. On a summer evening on the lawn of the Garrison Club, one of us boasted to a group of young officers from infantry and artillery that he was a tanker. Overhearing this conversation was Captain Shamshad, the regiment’s technical officer who had a dry sense of humor. The next morning, we were summoned to his office. “So, you all think you are tankers?” he asked with a sneer. “Have you ever seen the belly of a tank”? From a diagram in the tank manual, we knew what the bottom of the hull looked like with inspection plates, an escape hatch, bolts, drain plugs, etc. but admitted that we had never physically been under the tank. Whereupon he said, “You can’t call yourself a tanker unless you have seen the belly of a tank. Senior Subaltern, make sure they see the belly tomorrow.”

We had been joined by another second lieutenant from the academy and the next morning the five of us arrived in the tank park in our black overalls. The Senior Subaltern lined us in front of a tank and we were assigned as the tank commander, loader, gunner, driver, and co-driver. His order to ‘mount tank’ momentarily confused us as we were expecting to peer under it but we quickly clambered up and onto our respective seats. The next call we heard was ‘close hatches’ and we pulled them shut. By now we had a good idea of what was next and mentally prepared when we heard ‘Abandon Tank’.

If a tank is immobilized during combat and artillery and artillery and small arms fire makes it unsafe for the crew to escape from the top hatches, the drill in the Sherman is to use a hatch under the co-driver’s seat. The co-driver who was the first to go had a relatively easy exit. Folding his seat forward, he unlocked the hatch which fell down and he slithered out of the two-by-two-foot opening to the ground a foot and a half below. Then while he crawled out towards the rear of the tank, and as the rest of us followed, we had a close view of the belly of the tank. As we exited from the rear came the command ‘Crew Front’ and we were back where we started but our neat, clean, and well-pressed overalls were no longer black but a shade of earthy brown.

We were rather pleased with ourselves but then our hearts sank as we realized that Capt Shamshad was standing behind the Senior Subaltern. “Congratulations boys”, he said with a suspicious-looking smile, “You are now half tankers. Go back the way you came and you can then claim to be full tankers.”

Back at the club that evening we were joking and complimenting each other on how quickly we had exited and reentered the tank when Shamshad joined us. “Hey boys. Next week we will do it again but this time with a slight difference”. To our dismay, he explained that during combat, when a crew abandons a tank through the escape hatch, they should be prepared to get out and fight.

Author’s Note. If you liked reading this article and want to know more about the raising of 26th Cavalry and its war history in the 1971 Pakistan-India War, read my book Forged in the Furnace of Battle

Syed Ali Hamid is a retired Pakistan Army major general and a military historian. He can be contacted at syedali4955@gmail.com. All facts and information is the responsibility of the writer