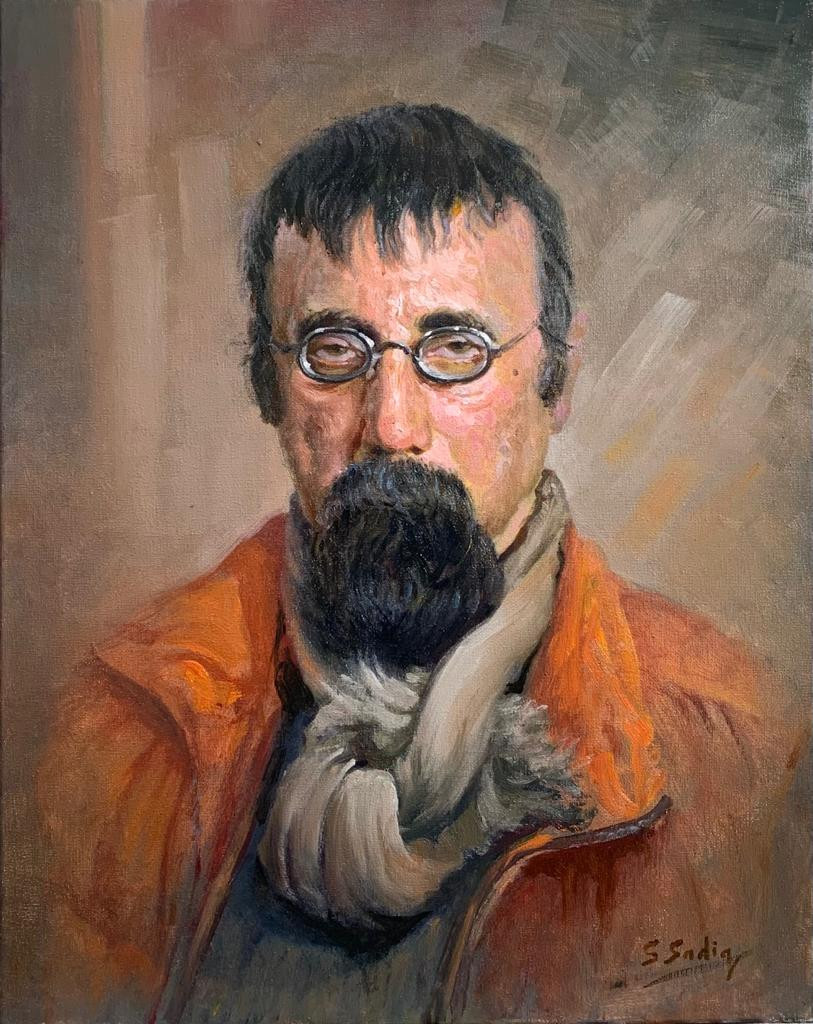

Mumtaz Hussain's flight of imagination has produced a collection of short stories that you may be unprepared for coming from the same writer. The themes of these fictive stories, under the title Portrait in Words, sprawl from nostalgia and heartbreak to lust and infidelity. Each story is accompanied by a painting by Hussain which he says captures its essence. The paintings in watercolour and gouache are as much a reflection of Hussain's edgy artistic prowess as the subjects of his prose. "To give visual illustration to my stories, I condensed the essence of the story into a painting. Images are a universal language," Hussain told The Express Tribune.

So it is the predominant literary device employed in the first and longest story of the book, The Barking Crow. The narrative spans a myriad of mythology and folklore from across world literature and traditions that feature crows, beginning from the indigenous fable of the clever crow that tried to drink water from a pot by filling it with stones to raise the level of the water.

Hussain expresses a keen interest in local folklore as it informs the cultural tradition of his Punjabi ancestors, and his roots.

"My background is rural Pakistan, so everything related to village life has influenced me. There, knowledge travelled through the oral. There are no scribes. Punjabi wisdom is all oral. The people are skillful storytellers. All this background has an effect on me and my art. It is an essential part of my inheritance," he explained.

There is a smattering of Greek mythology intermixed with the local traditions in his stories. "People don't realise that the Punjabi language is securing Greek mythology," he said. "The biggest example is Heer from the folk story of Heer Ranjha which is based on Zeus and Hera. Several Punjabi authors, including Waris Shah, have written about the roots of Greek mythology in our folklore. I would go as far as to say Punjabi is based on Greek mythology, our mysticism is based on Greek mythology."

Hussain wears many hats; writer, painter, graphic designer, filmmaker. Some of his stories lend credence to the idea that he is primarily a cinephile and filmmaker. These stories rely heavily on fast-changing scenes and a narration of moving images; others give a sense of having been written as cameo teleplays in their setting, dialogue and story arc. "Cinema is in my blood," he says. "These stories I write are like movies that run through my mind." Producing a film requires funds which are not easily available, so while he waits for things to fall into place for a film project, he writes. It is a form of catharsis for the artist who has made seven films in English, all based on Pakistan.

Talking about the process of writing, he uses the metaphor of flying a kite. The stories are like a tangled string of ideas that is unravelled when their words are put on paper. The finished form of the story feels like his thoughts are finally soaring on the wind like a kite.

His writing germinated when he was studying in film school. He consulted his teacher one day, saying, “I have so many ideas for films, what do I do with all these ideas?” The teacher advised him to jot down a synopsis of every idea to record it. Those notes are what turned into short stories.

Mumtaz says, this is the reason "why my stories are different from the classical short stories."

The first time he showed his stories to a publisher, that is the feedback he received.

"NCA, where I studied, was close to Sang-e-Meel, the biggest publisher of Urdu books. That's where I took my stories. When the publisher got back to me after reviewing my stories, he said, 'I read around 200 manuscripts per month by classical Punjabi writers. I know their style of writing. I have never come across something like your style. You are distinct,'" Hussain recalls his words.

Perhaps the publisher referred to Hussain's treatment of his subject matter; he peers through a kaleidoscopic lens on events that have impacted Pakistan's social fabric and political history and creates a hologram of the past and future manifestations of the event.

For instance, Poppy Cultivated in Heaven is about a lovesick, naive villager who gets into poppy farming during the Afghan war. His simple life is overtaken by something bigger than he can fathom when he starts selling to the Mujahideen. Until then, he was just a man confused about haram and halal, but when all around him men peddle the paradise promised to jihadis, he gets swept up in the zeitgeist of the time. The finale with him carrying the orders of a terrorist group and detonating a suicide vest is again a cinematic turn of events. The bomb explodes in sound, visions and words that are mystical, decimating his dreams of finding love and shattering the illusions of his religious indoctrination.

Virus Bomb is an even more cryptic story, laden with allusions and symbolism about a pregnant woman called Mary who goes to the UN HQ and later the Hague in search of justice for her dead husband and child. It is set in the backdrop of the Covid pandemic and the world is on the verge of a war. In this dystopian story, the bloodsucking Dracula presents himself in court and Batman delivers Mary's baby.

According to Hussain, he has turned the storytelling format on its head. Readers of this compilation might agree that his stories will stand out in their minds as avant garde introspection of Pakistan's sociopolitical transformation since the 1980s.