“As the global community moves towards multipolarity, we desperately need – and I have been vigorously advocating for – a strengthened and reformed multilateral architecture based on the UN Charter and international law to avoid fragmentation,” UN Secretary General António Guterres said while speaking at the BRICS summit in the South African city of Johannesburg late last month.

Guterres pointed out that today’s global governance structures were established in the aftermath of WWII, excluding many African countries still under colonial rule. He stressed the necessity for these institutions to reflect contemporary power dynamics and economic realities. Without such reforms, fragmentation becomes inevitable, warned the UN chief.

The BRICS summit produced a joint statement, called the Johannesburg Declaration, after three-day deliberations in which the grouping reiterated its commitment “to inclusive multilateralism and upholding international law, including the purposes and principles enshrined in the Charter of 2 the UN as its indispensable cornerstone, and the central role of the UN in an international system in which sovereign states cooperate to maintain peace and security, advance sustainable development”.

The BRICS nations also expressed “concern about the use of unilateral coercive measures, which are incompatible with the principles of the Charter of the UN and produce negative effects notably in the developing world. We reiterate our commitment to enhancing and improving global governance by promoting a more agile, effective, efficient, representative, democratic and accountable international and multilateral system.”

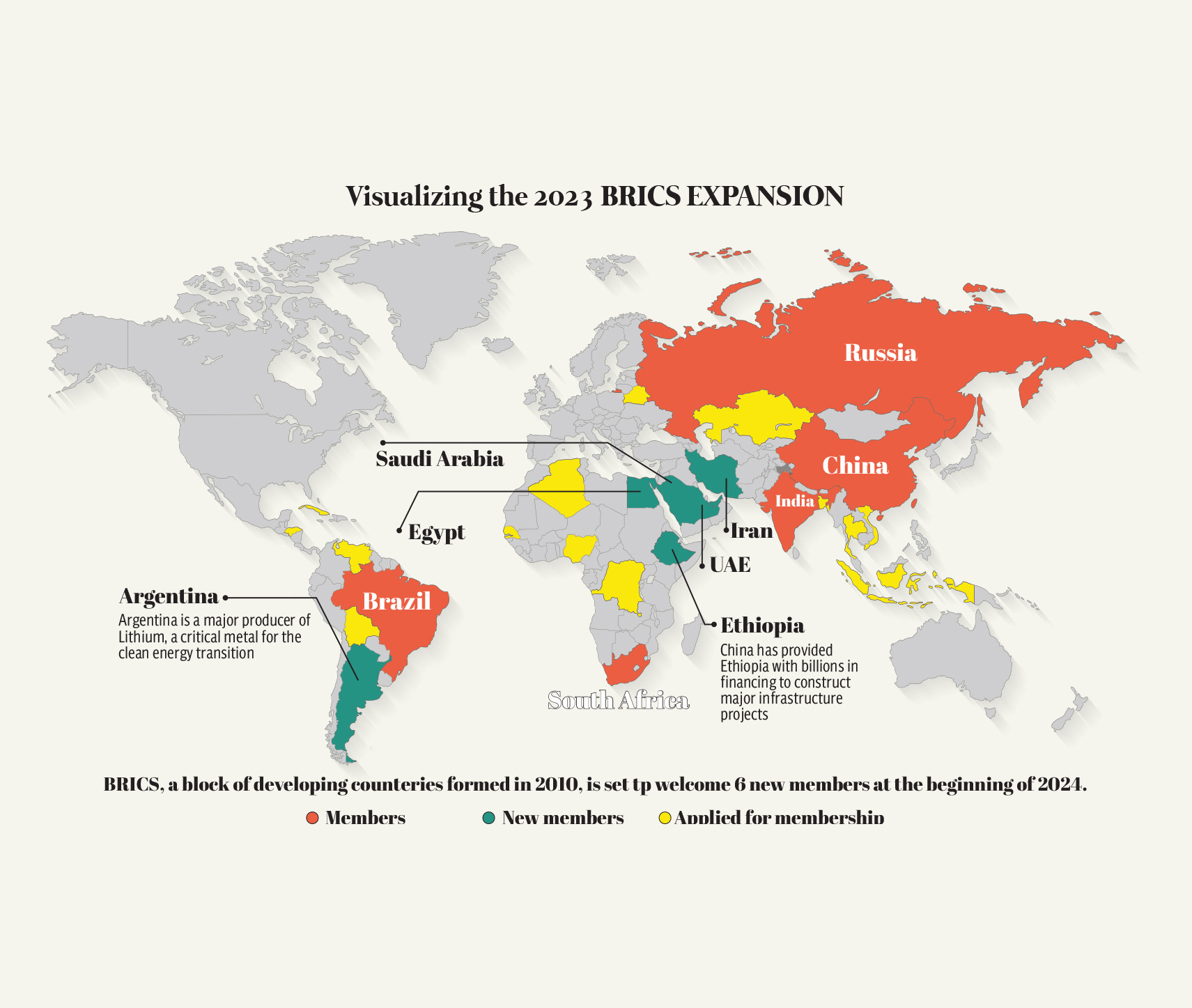

The most significant highlight of the 94-point Johannesburg Declaration was the bloc’s decision to admit Argentine, Egypt, Iran, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Ethiopia as full members of BRICS from January 1, 2024, out of the 22 countries that had formally applied for membership. “We appreciate the considerable interest shown by countries of the Global South in membership of BRICS. True to the BRICS spirit and commitment to inclusive multilateralism, BRICS countries reached consensus on the guiding principles, standards, criteria and procedures of the BRICS expansion process,” reads the declaration. This indicates further future enlargement of the bloc in an effort to seek a greater weight in international affairs.

In the run-up to the BRICS summit, the Western media’s frenzied chattering rose to a crescendo as it sought to portray the huddle as an attempt by the China-led Global South to turn the “club” into a “geopolitical force that can challenge the West’s dominance in world affairs.” It also tried to trump up differences among BRICS nations over its expansion as the summit was scheduled to admit new entrants. A Western news agency even cooked up a story on the authority of “sources” that Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi was unlikely to attend the conclave. Foreign Minister Jaishankar had to quash the “rumour”, leading his South African counterpart, Naledi Pandor, to conclude that “someone was trying to spoil our summit.” The Western media also played up the complex nature of relations between BRICS nations, especially India and China, and their differing approaches towards the West.

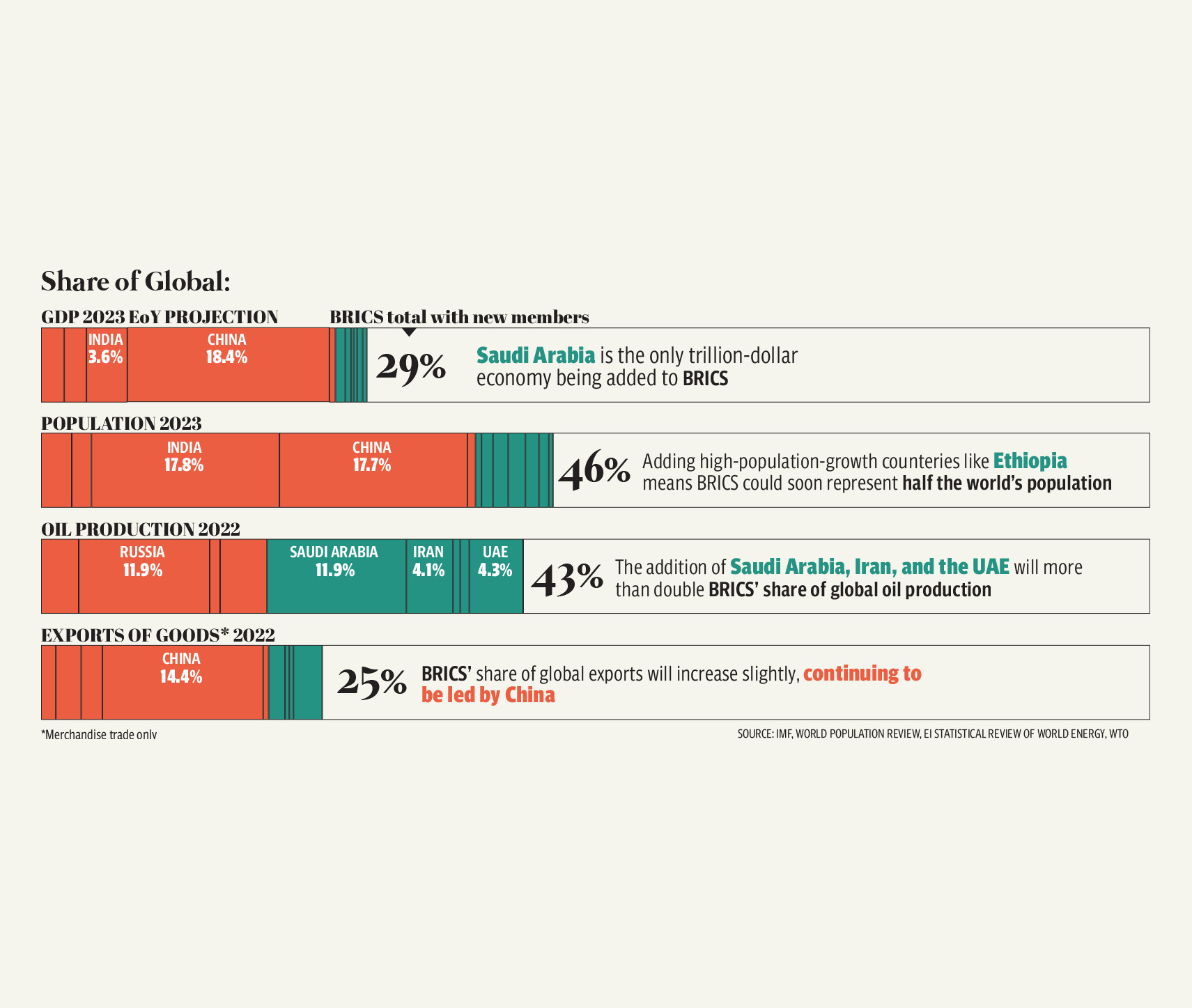

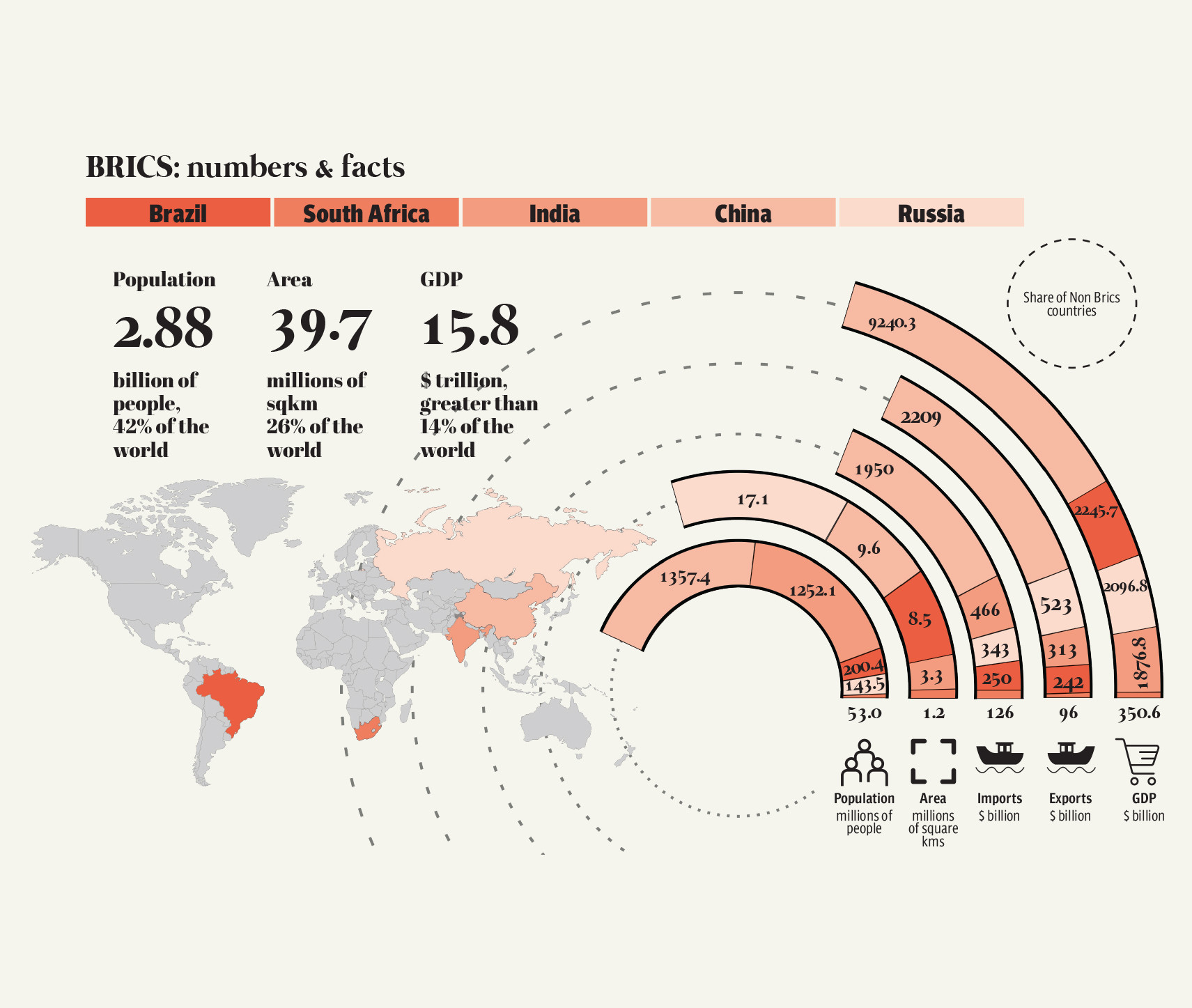

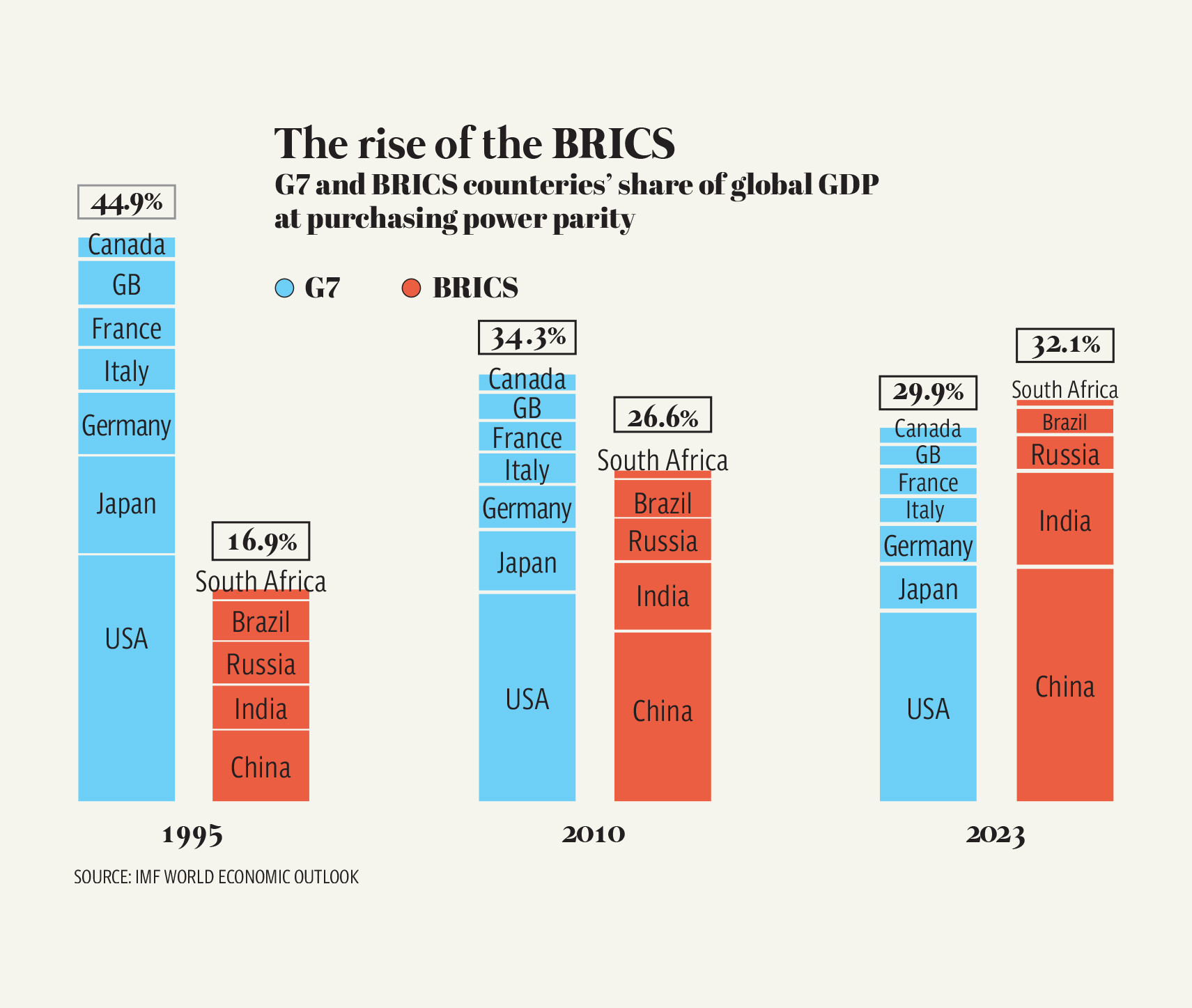

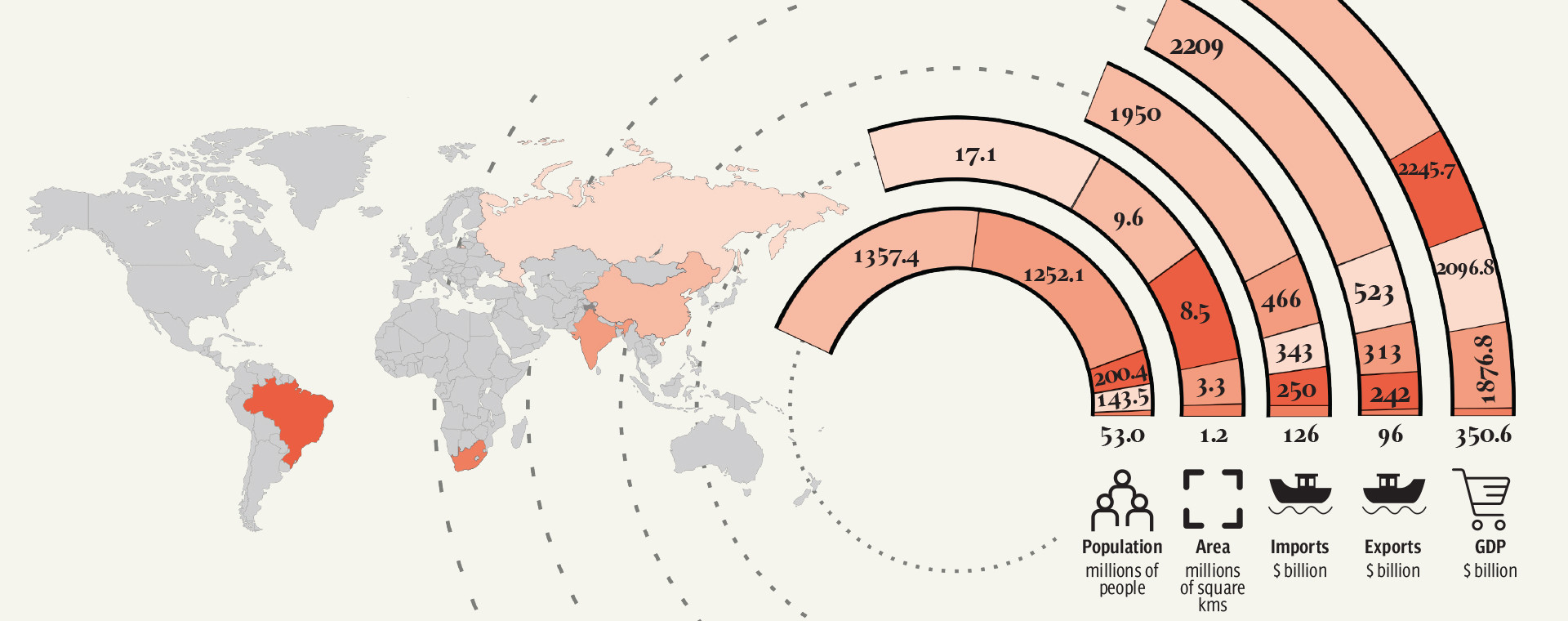

This is not the first time. The West’s global narrative-shaping media has repeatedly tried to stymie the bloc’s growth through concerted campaigns. This begs the question: why BRICS has become a worry for the West? There could be several possible reasons. First, the West fears that BRICS could become a systemic rival to G7 (the United States, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, and the United Kingdom) which enjoys undisputed monopoly over international financial affairs and thereby dictates global agenda. These fears stem from the compelling fact that BRICS contains the two most populous nations and the leading countries on three continents; produce one-third of the world’s food; and has an aggregated GDP of 31.5%, which surpasses G7’s GDP of 30.7%. Moreover, the allure of BRICS is such that it has attracted the countries that have long been key US allies in the Gulf region and northern Africa.

Second, the US fears that BRICS might be used by rival China to threaten the “liberal rule-based” world order that the West believes it has been divinely tasked to protect and promote. The US draws much of its unprecedented power from the overwhelming success of the alliances and coalitions it has cobbled up and led as a foreign policy tool to achieve its geopolitical objectives. In BRICS, the US strategists now see a potential rival alliance of the Global South motivated by a desire to reconfigure the world order and threaten the Western geopolitical interests in the world. This is notwithstanding the fact that BRICS is not a NATO-style alliance nor do its members see it as one, as it allows them to chart their individual course on international issues. The BRICS nations reiterated this commitment in the Johannesburg Declaration: “We believe that multilateral cooperation is essential to limit the risks stemming from geopolitical and geoeconomic fragmentation and intensify efforts on areas of mutual interest.”

Third, two key US allies in the Middle East – Saudi Arabia and the UAE – joining BRICS might also be unsettling. The move indicates the two oil behemoths are drifting away from the West after becoming disillusioned by declining US engagements in the region. They started feeling, particularly during the past two US administrations, that they could not rely on their “ironclad alliance” with the West for their strategic interest and security. The Yemen and Syria wars and China-brokered rapprochement drive have apparently changed security paradigms in the Gulf region. The Johannesburg Declaration welcomed “positive developments” in the Middle East, especially the détente between Riyadh and Tehran, readmission of Syria into the Arab League, and reaffirmed support for Yemen’s sovereignty and territorial integrity.

Fourth, the US fears that as BRICS expands and strengthens, it may move to dethrone the “king dollar” which has been ruling global financial transactions since the end of World War-II. This privileged status of the greenback has lent colossal power to the US to use its currency as a tool to implement its geopolitical agenda globally. The dollar’s hegemony in the financial world and the strategic power it bestows on the US has long induced a desire to de-dollarize global trade. BRICS nations have been trying for a decade to launch a common currency, but their efforts have hit snags as 58% of global foreign exchange reserves remain in the dollar. The Ukraine war has given a fresh impetus to the de-dollarisation drive as Russia, China, and Brazil have decided to ditch the dollar for cross-border transactions and shift their reserves into gold.

Now, the admission of Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Iran might spell the end of the petrodollar’s long reign. With the three oil giants on board, BRICS would make up almost 42% of global crude oil output – and this economic clout might brighten the bloc’s chances of deploying alternative currencies. The Johannesburg Declaration made no secret of this de-dollarisation desire. “We stress the importance of encouraging the use of local currencies in international trade and financial transactions between BRICS as well as their trading partners. We also encourage strengthening of correspondent banking networks between the BRICS countries and enabling settlements in the local currencies,” it states.

Design by: Mohsin Alam

Today, we see a major shift towards a multipolar world which requires global multilateral institutions, like the UN, World Bank, and IMF, to support this seismic shift for a world of shared prosperity. Development should not be an exclusive privilege of the Global North. “We cannot afford a world with a divided global economy and financial system… and with conflicting security frameworks,” the UN chief said at the Johannesburg summit. And BRICS nations unequivocally stated in their joint statement that they “encourage multilateral financial institutions and international organisations to play a constructive role in building global consensus on economic policies and preventing systemic risks of economic disruption and financial fragmentation”. However, at the same time the grouping called for greater representation of emerging markets and developing countries in international organisations and multilateral fora.

In this defining moment in world history, the international community has to make a choice between dialogue and confrontation, and cooperation and conflict while keeping in mind that “humanity will not be able to solve its common problems” in a fragmented world mired in crises.