In 2020, just like the rest of the world, Hassan found herself confined to the four walls of her family home. There were household responsibilities and chores to attend to, and of course, making tea for a family of eight, twice a day.

During lockdown, she remembers feeling burdened and overwhelmed by household responsibilities, especially the tea-making, whereas in the tie that lockdown provided she would rather be focussing on creating a relatable concept for her thesis at university.

“I felt as though I was trapped inside a teabag,” she expressed.

Wondering how many other women felt the same, she began to speak to women from different sectors and backgrounds of Karachi. To her surprise, or lack thereof, countless women were also being subjected to abuse, taunts and toxicity and felt imprisoned inside a cup of tea.

Throughout her formative years, Hassan has been a naturally-skilled artist, but she never thought of art as a viable career option. It was only after completing her O-levels that she took a leap of faith to pursue her path in the artistic world. In 2017 she graduated with a Fine Arts Bachelors from the University of Karachi, with an academic achievement award. This is when she began working with elements of tea showcasing complexities of female fragility, suffocation and burdens.

Her work has been displayed at various group shows and art galleries. She was the anointed project lead for MANACHI project between Manchester Museum and Karachi University, in collaboration with the State Bank of Pakistan and the British Council. She also co-curating the creative collection of the book named "Manachi". Currently, she is working towards a Masters in Fine Art from a reputable university abroad.

The irony, as Hassan puts it, is that while tea is a motif to connect families, friends and even strangers, it is also a way to induce hatred and cast judgment. This revelation became the driving force behind her thesis and art, and she began exploring the themes in her artwork.

Being a woman is to perform

Women are expected to perform well, in every aspect of life while maintaining their gracefulness, only to be mocked, compared and be prepared to let their inner potential wasted. And with all of this, they are suffocated under the burden of expectations of household chores as simple as tea-making.

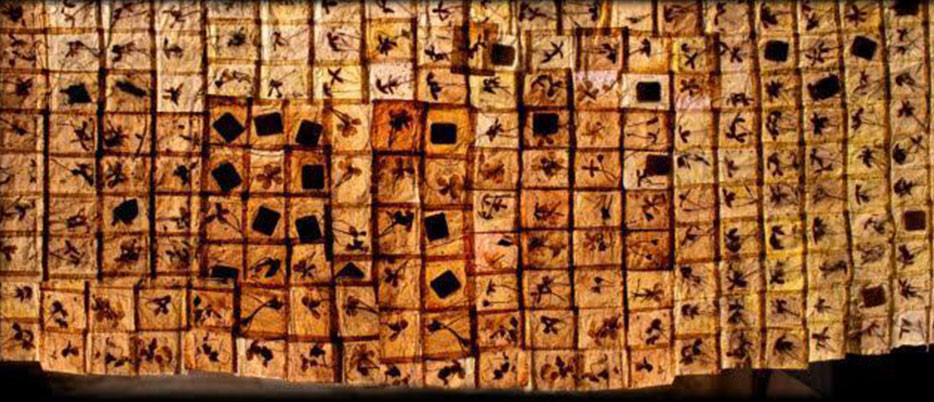

Hassan’s work reflects her satirical and and rebellious attitude towards the meaningless or demeaning traditions and norms followed in our society. Through her art, she pays a tribute to the bravery, resilience and helplessness of women.

“My work impressions emphasise the societal feeling of suffocation and despair while being in the act of obedience that entails preparation of and setting the table and hosting the family every day as well as entertaining frequent guests. Surely, we’ve all been there,” she highlights.

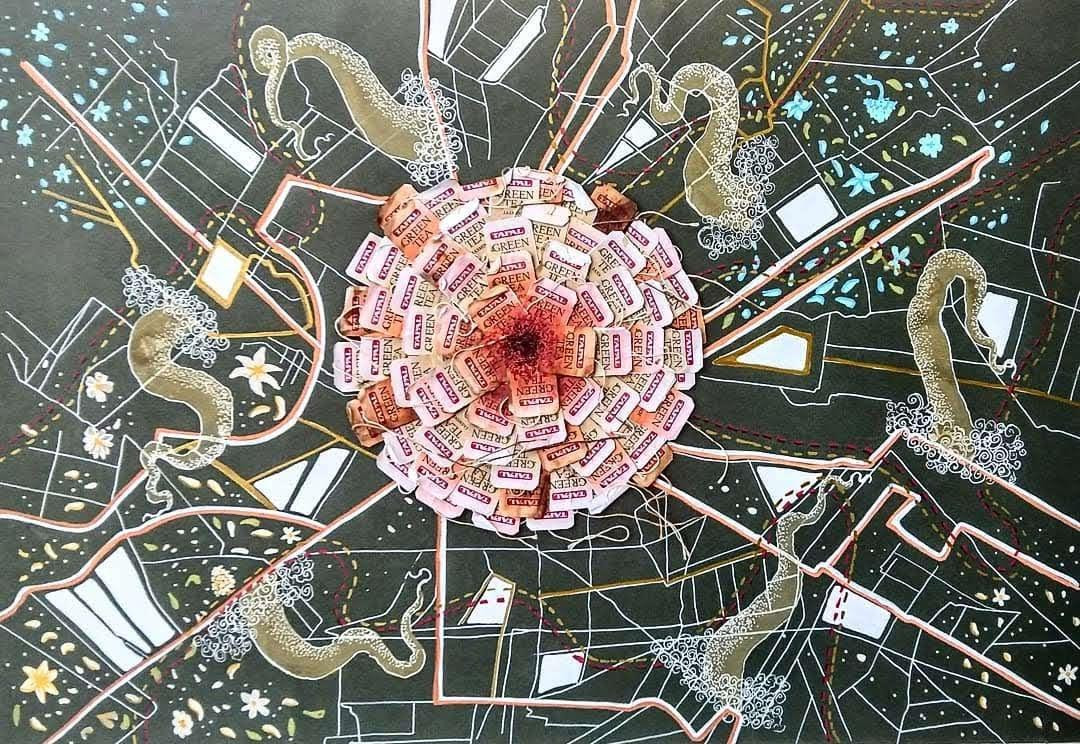

Through the use of pressed organic flowers and tea bags, she portrays the emotional and physical stress women go through on a daily basis, where brain-drain is imminent and inner peace is “squeezed-out” like tea in a teabag. The dried flowers express a woman's love and aura caught in a tiny teabag without a way out.

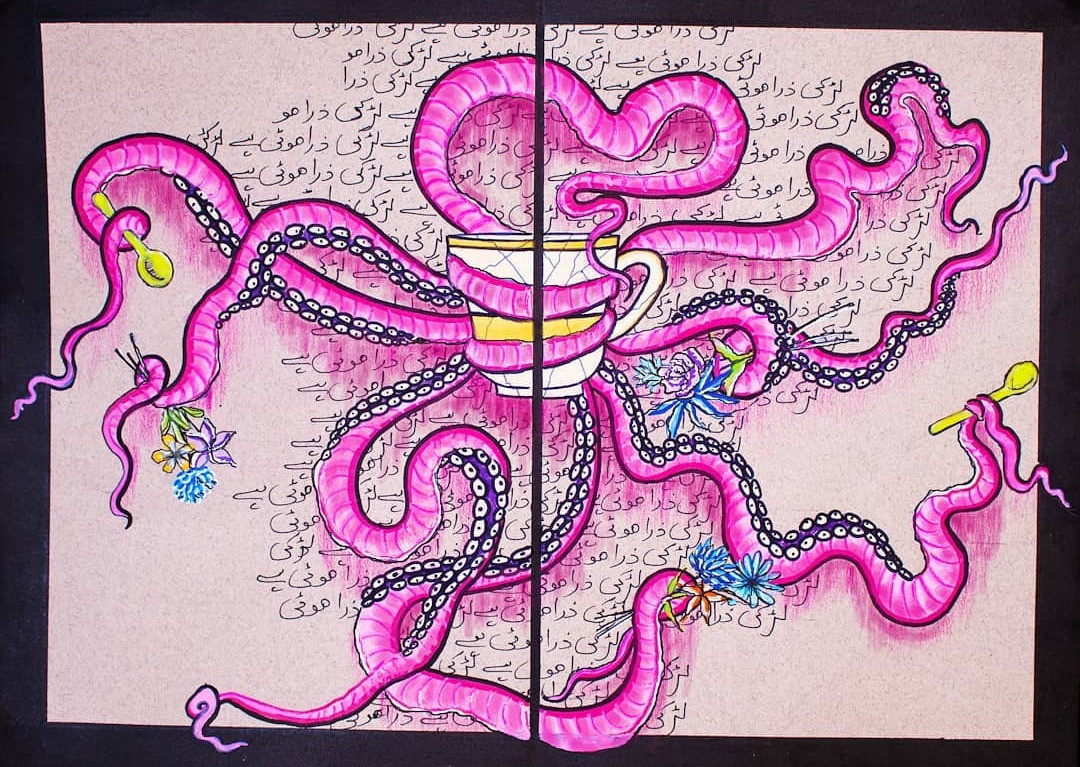

She draws parallels between women and an octopus, a creature that has three hearts, nine brains and eight arms, but both being incredibly smart, creative and fluid. Hassan thinks life would be easier for women if they were like an octopus, possessing multiple arms and legs to perform the plethora of tasks designated upon women.

“I feel a woman does a lot with just two hands.”

Redefining femininity beyond perfection

Through her engrossing art, she raises questions about societal expectations of female perfection in all spheres of life, advocating for acceptance of their flaws and finding beauty in it. She champions Rumi’s idea that there is a crack in everything God has created, the gap is where the light gets in.

She challenges society to enjoy their cup of tea without associating it to one’s moral character. She rejects the idea that women must follow a checklist and highlights that women are made for far more complex and a multitude of roles than preparing tea.

Her artistic expressions also align with Judith Butler’s theory of gender performativity which states that masculine and feminine roles are not biologically fixed but rather socially constructed.

A national obsession

Hassan’s choice of using tea as an instrument is deeply intertwined with Pakistan’s obsession with this cherished beverage. Chai (tea) is very much embedded in our culture and it can be easily said that it is a huge part of who we are.

It's a household essential that exists in a variety and abundance irrespective of inflation or affordability issues. Pakistanis enjoy a bewildering array of tea choices; doodh patti, karrak chai, Kashmiri chai, masala chai, tandoori chai, herbal tea and even the good old danedar [granular] tea bag.

Some people have tea either in the mornings or evenings, but most prefer it twice a day, while there are many who don’t need an excuse to have tea or anything is an excuse for them to have tea several times a day. In this way, tea shapes not only schedules but also centres round lifestyles, creating an unbreakable cultural bond.

It connects families on special occasions such as Eid, weddings or social gatherings such as watching cricket matches together, moviethons etc. It also unifies them on just about any day to sit and unwind with family or friends over a cup of tea. Guests never leave without having a cup of tea, and even the slightest hint of rain triggers the cultural need for tea. It is an age-old quick remedy for headaches, cure for boredom and a buffer/filler for awkward conversations.

This culture of tea-drinking gave rise to dhabas [roadside restaurants], where you sit down and have tea after a long day of work. At the same time, rishtas [marriage proposals] are finalised over a cup of chai, and from college friends in the cafeteria to aunties in their posh drawing room, all find solace in their tea-parties to relax and gossip.

This tea obsession took a human form in 2016, when a blue-eyed chai-wallah was photographed at Islamabad's Sunday Bazaar, and became an overnight sensation. After all, he possessed two things we love most; good looks and knowing how to make tea.

In 2022, Pakistanis had a meltdown [also on the internet] when Ahsan Iqbal, Federal Minister for Planning and Development, told the nation to reduce their tea consumption by one or two cups per day to save forex reserves, because tea imports were putting additional financial strain on the government.

Tea is a socially accepted addiction in the sense that it is weirder if you’re not addicted to it. Yet this tradition, like many others, does not come without baggage.

It's not so much the tea itself that’s the problem, but rather the burdens and expectations around brewing the perfect cup of tea, which as Hassan highlights more often than not disproportionately falls on women, who are held under a microscope, judged by the quality and perfection of a cup of tea. Chai bohat achhi banaati hai hamari beti [our daughter makes very nice tea], is the opening line for describing the daughters’ skills and achievements to the prospective in-laws at the time of their marriage proposal.

Quest for acceptance

Through her art, Hassan challenges traditional gender roles and expectations, urging for women to be viewed beyond perfection. She wilfully rejects the onus of their being, narrowed down to a cup of tea. Her work is an important reminder to keep pushing for societal progression when it comes to not only equal rights, but also equal expectations for all genders.