The memory of the Battle of Karbala is as old as time itself. According to a hadith in Bihar Al-Anwar [a comprehensive collection of traditions or ahadith compiled by Shia scholar Mohammad-Baqer Majlesi ] Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) once gave his wife, Hazrat Umme-Salma a sack full of sand from Karbala. He told her that Allah had foretold the shahadat [martyrdom] of his grandson Imam Hussain in Karbala and that she should keep the sand safe with her until the day that she sees that the sand has taken the colour of blood. That day she would know that Imam Hussain had been slain.

The Battle of Karbala has been regarded as one of the most significant events in Islamic history by both Shias and Sunnis. The battle took place in the city of Karbala in Iraq, on Muharram 10, 61AH (680 AD), on the banks of the River Euphrates. This battle is considered to be the epitome of the fight between good and evil, where Yazid I had sent troops of thousands of men against a small group of 72 men and the harem led by Imam Hussain. On Muharrum 7, the Yazidi Army shut off water and food access for them and on Muharrum 10, the battle started and ended by asr time [late afternoon] with the death of Imam Hussain (AS).

When Imam Hussain (AS)’s son, Imam Ali Zain-ul-Abedin (AS) finally entered Madinah, after being released from the jail in Yazid’s palace in Damascus, the first majlis preceded, mourning the Ahl-ul-Bayt [the family of the Prophet] and all the atrocities borne by them. The tradition of grieving and mourning in the first 10 days of Muharram leading up to the chehlum (the 40th day of passing, an important observation after death) has carried on ever since.

The history of Islam and the Indian Sub-continent goes back to the time of Hazrat Ali (AS) when missionaries were sent to preach Islam. They entered through the Makran coast and had some success in Sindh. The first majlis held in South Asia is said to have been observed during the Fatimid Rule in Multan (972-1026), which then was considered to be a part of Sindh. The Fatimid Caliphs trace their lineage from the Prophet (PBUH)’s daughter Hazrat Fatima (AS) and through her son Imam Hussain (AS).

After the Fatimids were removed from Sindh by Ghanzavids, the Muharram observations were violently suppressed. The Ghaznavids were backed by the Abbasids who were vehemently opposed to the Shias and there were massacres which almost eliminated the entire Ismaili population in the Subcontinent. But with the arrival of the Mughals, Muharrum processions were brought in with full fervour. Especially when Humayun regained control of the subcontinent after defeating Sher Shah Suri, he allocated many lands for building Imam Barrahs and supported Muharram processors. Before, when Humayun had been exiled by Sher Shah Suri he was taken under the wing of the Safavids and he converted to the Shia faith. Whether or not Humayun converted for political reasons is up for debate, but he set a precedent for Muharram commemorations for his descendants.

During the time of Akbar, Muharrum processions were also an important event which even the Emperor participated. Public mourning of Muharram in Mughals continued in Mughal cities until Aurangzeb came along. The central space of Muharrum celebrations in the subcontinent was Lucknow where Nawab Asif-ud-Daulah created spaces for Muharrum observances and held Majalis in his courts where he donned the garment of mourning alongside his officials. Tipu Sultan also commemorated Muharram with dedication. Similarly, many other regions in South Asia, such as Kashmir were holding large jaloos [processions] and majalis during this time.

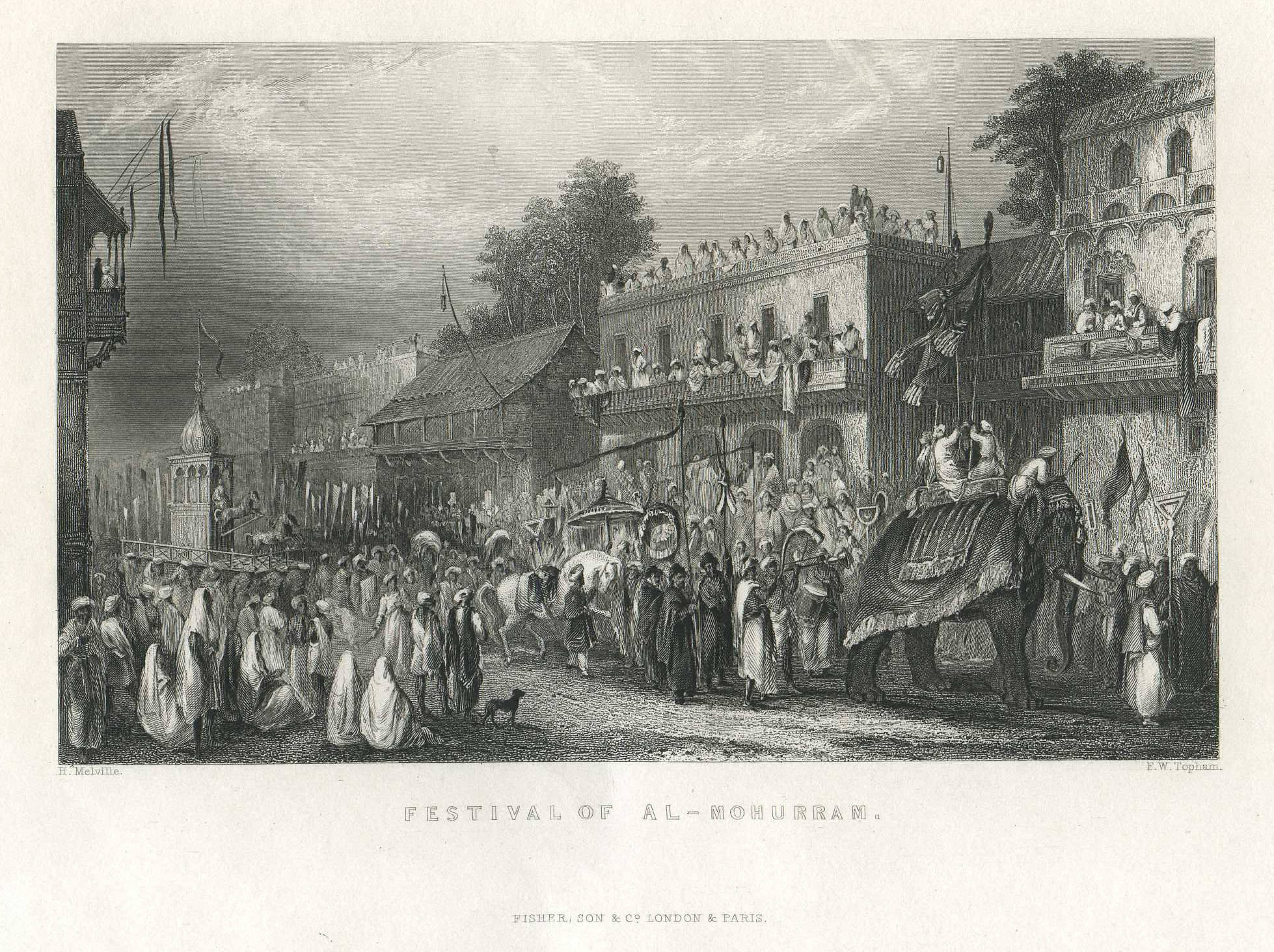

Muharrum celebrations caught the special attention of colonials to whom massive gatherings of mourning and its arts were extremely fascinating. There are many accounts of British colonials describing the scenes of Muharrum. Rudyard Kipling describes the scene of the Ashura procession as follows:

“… and beating their breasts, the brass bands were playing their loudest, and at every corner where space allowed, Mohammedan preachers were telling the lamentable story of the death of the Martyrs. It was impossible to move except with the crowd.”

They were enraptured by the scene of the Indian cities and courts. But as they came to power, Muharrum processions appeared to them as an opposition to their authority as flocks of people gathered making urban regions beyond their control. This made the insecure and many restrictions and oppressions of such activity came about. Although back in their own land, Muharrum was portrayed as this exotic event of the unruly Orient, where colourful postcards depicting the jaloos were very popular. To quench their colonial fantasies, many paintings and illustrations were produced to show the “quirks” of India. For this reason, the genre of Company Paintings has perhaps the largest number of paintings created on the subject.

While in common understanding the observance of Muharram may be linked with Shia Muslims, but in reality that has never been the case. Sunnis and Hindus in the subcontinent have been known to play a significant role in the rituals of Muharram and their contributions can be observed alongside the Shias through art and traditions throughout the history of South Asia.

Within the arts of Muharram, perhaps the most important of them all is poetry in the form of noha, marsiya, and soaz. These forms of poetry tell the tale of Karbala and all that happened to the family of Imam Hussain and his companions. One of the most popular marsiyas today date back to the 18th century and was written by a Hindu poet, who later converted to Islam. This noha is ‘Ghabraye gi Zainab, written by Munshi Chunoolal, and is recited at Shaam-e-Ghareeban majlis even today.

Other Urdu and Persian poets were also writing verses on the subject for centuries. The first marsiya in Urdu was written by Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah, in the 1500s, who writes:

“Come O! Muharram, let us cry and grieve and shed our blood remembering our Imam”

The most famous writer of Urdu marsiya is Mir Anees was from Lucknow and the legacy of the azadari [mourning] in this region still lives through him. Similarly, his contemporary, Ghalib also wrote verses in the praise of Imam Hussain (AS). His affiliation with Imam Hussain (AS) and by extension the Panjatan [The Blessed Five] comes from his mother, who was a Kashmiri, and Kashmir a Shia majority region.

Another tradition of the Muharram azadari is the taziya. Taziyas are structures built over the first nine days of Muharrum and then taken out in processions on the day of Ashura, which is the 10th day of Muharrum, the day of Battle of Karbala. The word ‘taziya’ comes from the Arabic word ‘taziyat’, meaning offering condolences. A taziya is a structure that represents the tomb of Imam Hussain (AS) in Karbala. It is believed that when the infamous ancestor of the Mughals, Tamerlane, was returning to Central Asia from the ziyarat [pious visitation] of Karbala, he wanted to build a structure that represented the mausoleum and could remind everyone of the sufferings of Karbala. So he built the first taziya in Delhi. Some say that the taziya at Nizamuddin Auliya’s darbar is the one that Tamerlane built. Taziyas were then made famous by Nawab of Lucknow, Asif-ud-Daulah. Another famous region known for its taziyas is Chiniot, where master craftsmen have been building exquisitely carved taziyas for generations.

Alam-e-Abbas is another prominent artefact from the processions in Muharram. The alam is the flag that represents an army. Hazrat Abbas (AS) was the brother of Imam Hussain (AS) and the commander and chief of his army. He was carrying the alam in the battle and on his way to fetch water from the Euphrates, where he was martyred, both of his hands were cut. Therefore, an alam usually features an ornate symbol of a hand at the top. On the flag part of the alam the name Ya Abbas, Ya Hussain or Ya Ali is written.

The alam was introduced in 1380 by an Iranian Sufi saint, Syed Khawaja Syed Makhdoom Ashraf Jahangir Semnani. A famous painting from the time of Nawab Asif ud Daulah shows the court in mourning. The background is decorated with alams of red and green. Bihar-ul-Anwar talks about the significance of these colours, with green representing Imam Hasan (AS) who was given poison by conspiracy and red the colour of Imam Hussain (AS) and his sacrifice in Karbala.

Muharrum celebrations are deeply tied with the identities of Muslims in South Asia, with the majlis and jaloos being religious celebrations of both Sunnis and Shia. Not only do they mourn the death of the Prophet (PBUH)’s grandson, but celebrate the eternal victory of good over evil, because for as long as people weep over the sajda of Hussain (AS), the evils of Yazid and ibn Ziyad are vanquished. Hussaini Brahmins, a sect of Hindus, bring solidarity to this cause by participating in this lamentation. Art has become an essential practice of mourning and continues even today with poetry, taziya, and alams.

The writer is a visual artist and researcher. You can follow her work on Instagram @luluwa.lokhandwala

All facts and information are the sole responsibility of the writer