It has been ten years since the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, the multibillion-dollar flagship project under President Xi Jinping’s $1.4 trillion Belt and Road Initiative, was launched. The gigantic BRI programme, 11 times the size of the Marshall Plan that rebuilt Europe from the ruins of World War II, aims to revive the fabled “Silk Road” through new roads, high-speed rail, power plants, pipelines, ports and airports, and telecommunications links to boost trade with 60 countries in Asia, Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa.

The BRI has been described by former US assistant defence secretary Chas Freeman as “potentially the most transformative engineering effort in human history” because, once completed, it could cover more than half of world’s population and generate a GDP of over $21 trillion. The project includes no military component, but American analysts fear it could potentially upend global geopolitics as well as geo-economics and challenge the US-led world order.

These apprehensions sparked vociferous debates in Western media in which analysts sought to portray BRI as a “debt-trap” that, according to them, ensnares developing nations in unsustainable debts through “predatory lending” and allows China undue influence over their policies. The term “debt trap diplomacy” was first coined by Western policymakers in 2017 to describe the Chinese takeover of Sri Lanka’s Hambantota port on a 99-year lease after the island nation failed to honour its debt commitments. Since then, the term has been unscrupulously applied to all BRI projects, including CPEC.

Design by: Ibrahim Yahya

CPEC was announced in 2013 during the visit of then Chinese Premier Li Keqiang to Pakistan, but it received a huge impetus in April 2015 when President Xi toured the country. The project was described as a “game changer” by Pakistani officials which they believed would end a chronic energy crisis, overhaul the aging infrastructure, establish industrial parks and open up the possibilities of transit trade to China through Gwadar Port with the help of a new network of roads. The $62 billion economic corridor further strengthened the decades-old strategic relationship which the two nations have described with a bevy of romantic adjectives. Pakistan, on its part, hailed CPEC as a journey towards “economic regionalisation in the globalised world” and as a “hope of better region with peace, development and growth of economy”.

The launch of CPEC was crucial for Pakistan for several reasons. First, it came at a time when the country’s security situation was extremely volatile with terrorists carrying out deadly attacks almost on a daily basis. Second, Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) had almost dried up due to the rampant security concerns spawned by the wave of terrorism. Pakistan had not seen much FDI since the exit of Pervez Musharraf from power who attracted significant foreign investments in the services sector through his liberalisation policy in the early 2000s. Third, Pakistan was struggling to overcome a chronic electricity crisis that stymied industrial growth and triggered violent protests by domestic consumers despite the governments giving billions of rupees in subsidies to save their “political capital”. Fourth, the country was in the grip of macroeconomic instability, marked by dwindling foreign exchange reserves, depreciation of its currency on the back of widening current account and trade deficits. Fifth, the country found it difficult to carry out mega infrastructure projects and make significant allocations for socio-economic development.

Against this backdrop, CPEC, especially its $43 billion early harvest projects, lifted spirits and expectations. Pakistan saw panacea of all its economic ills in CPEC which, it envisioned, would (a.) modernise infrastructure for long-term growth; (b.) connect major economic regions with a view to reduce regional economic development gaps; (c.) upgrade development, with the help of Chinese aid and investment; (d.) upscale investment relations with China to promote exports, and grow the industry and employment; and form industry clusters.

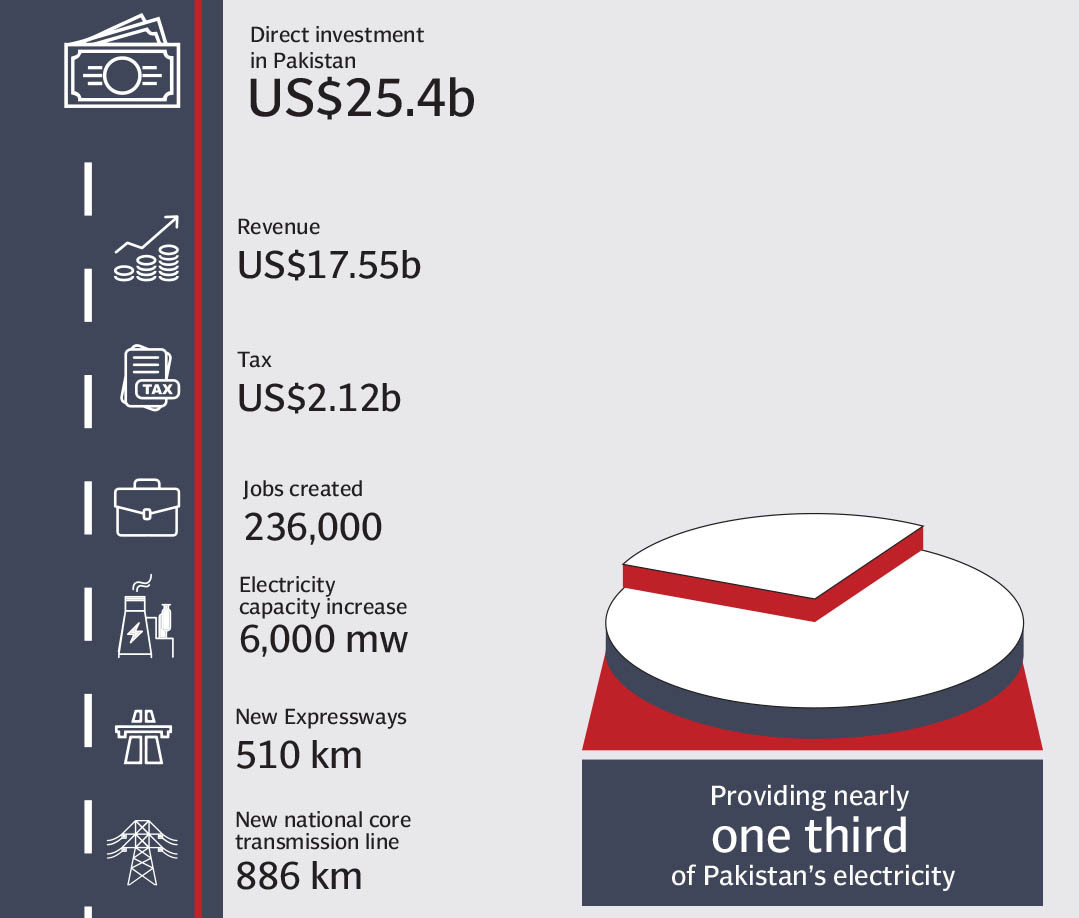

Although the CPEC progress has slowed down in the wake of a debilitating economic crisis since 2018, still this gigantic project has yielded a number of road and energy projects. “Multiple highway construction programmes are progressing on schedule. Power plants that have entered commercial operation provide nearly one-third of Pakistan’s national electricity demand, having changed the situation of power shortage in Pakistan,” China's National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) said in a CPEC update on May 17, 2023. “The Gwadar port, co-built by China and Pakistan, has made great progress in creating a regional logistics hub and industrial base. In addition, the construction of the first phase of the Rashakai Special Economic Zone in Pakistan has been completed and achieved positive results in business attraction,” the NDRC further stated. This unprecedented economic activity created 236,000 jobs, 155,000 of them for Pakistani workers.

Design by: Ibrahim Yahya

Nevertheless, Western analysts say that while Beijing and Islamabad have ardently sought to control the narrative on CPEC, details of the colossal project, including the terms of the investments and loans, the full extent of the projects, and the overall cost to Pakistan, remain murky. The US Department of State has also spoken out in recent months against what it sees as “China’s predatory lending to Pakistan” for possible geostrategic objectives. It argues that CPEC’s terms benefit Chinese companies and workers, and are unsustainable for Pakistan, leading to its rising debt burden. According to latest estimates, Pakistan’s external debt soared past $100 billion as of February 2023. And one-third of this, or more than $30 billion, is owed to China.

As a matter of fact, this is skewed analysis of this project based on perceived fears. It would be simplistic to look at CPEC as a project of bilateral governmental investment to entrap Pakistan in debt burden. CPEC has brought in Chinese private investments in diverse fields. A Chinese consortium has bought 40% shares in Pakistan Stock Exchange, Alibaba Group has acquired a 45% stake in Telenor Microfinance Bank, two Chinese companies will be setting up a smartphone manufacturing plant in Faisalabad, and China’s Hui Coastal Brewery and Distillery has started producing beer in Hub, Balochistan. These private Chinese investments have created employment and economic opportunities across Pakistan.

Non-interference in internal affairs of other sovereign states is one of the cardinal principles of China’s foreign policy. This is the reason Beijing has thus far refrained from meddling in Pakistan’s internal politics, or creating social pressure groups, or influencing its economic policies despite being its single largest lender. On the contrary, the Western multilateral financial institutions, especially the International Monetary Fund and World Bank, have repeatedly sought to dictate Islamabad’s fiscal policies. Similarly, the Paris Club creditors, especially the United States, France, Germany and Japan to whom Pakistan owes $8.5 billion, have also frequently used their influence for geopolitical and geostrategic purposes.

Having said that, Pakistan’s ruling elite has to ensure political stability and continuity of policies, improve security, and introduce broad-based economic reforms in order to reap full benefits of CPEC, which aims to transform Pakistan into a prosperous regional trade hub.