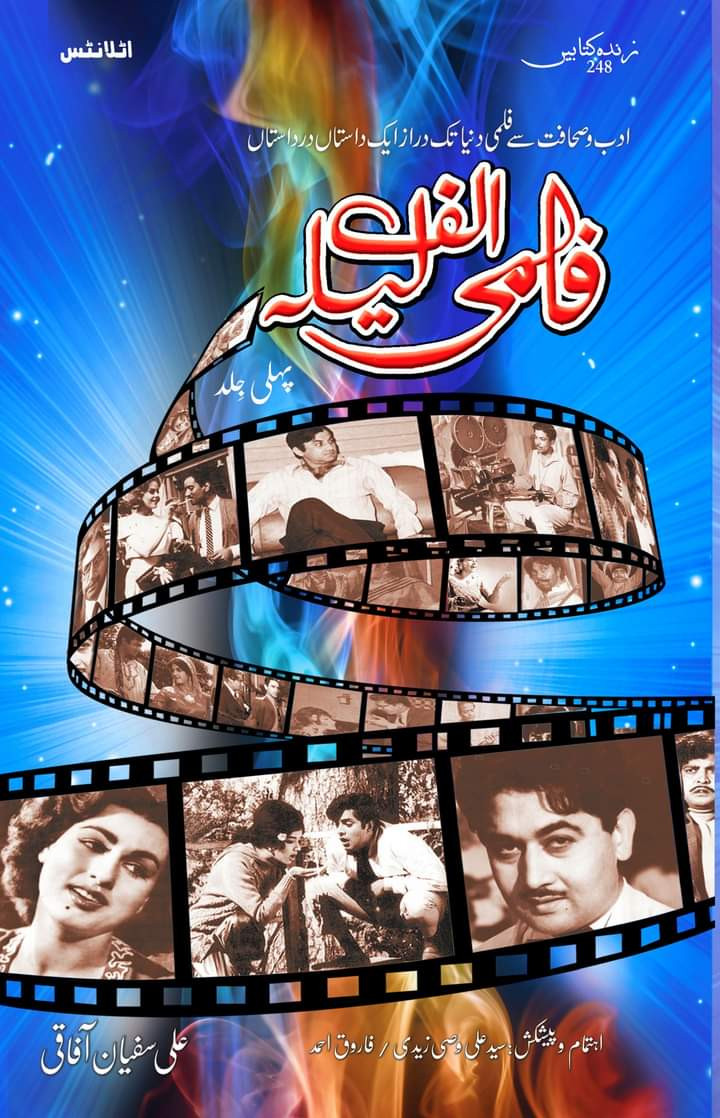

Ever wondered what issues filmmakers of yesteryear had to face when they decided to produce films in a newly-created Pakistan in the late 1940s? How did they manage to create magic for the entertainment-deprived audience without little or no resources? What made many of them quit their successful careers in United India and migrate to a country where they had to start from scratch? Veteran journalist turned filmmaker Ali Sufyan Afaqi’s Filmi Alif Laila is one series that not only has answers to these questions, but also takes you back in time when the film industry was in its nascent state, and the only visual medium for entertainment was cinema.

Before you move ahead, you should know Afaqi’s credentials. He wasn’t just a maverick film journalist, but someone who migrated from reporting on films to writing stories and screenplays, before turning to production and direction. Not only was his talent was behind some of the most popular films of the 1960s and the 1970s, but he also shared an excellent rapport with actors, actresses, directors, and producers of his time. From introducing Syed Kemal to Pakistani cinema to founding the template of film interviews in the country, he was one of the best journalists to report on films, film stars, and their lives behind the camera.

It was during the 1990s that he decided to pen his memoirs on a weekly basis and Filmi Alif Laila was born. The column was published in the popular Urdu digest Sarguzasht for two decades, and the first volume of the Filmi Alif Laila series features the columns that appeared in print between July 1994 and April 1995. It wouldn’t be incorrect to say that like One Thousand and One Nights that roughly translates in Urdu to Alif Laila, the columns takes you to another world and just when it seems that the story is about to end, another story is born out of nowhere, keeping the readers’ interest intact.

So, if you ever want to visit the early days of the Pakistan film industry, instead of a time machine what you need is a copy of Filmi Alif Laila, because not only does it takes you back in time but also provides you with a point of view from someone who was a prominent member of the film industry for nearly 50 years. If one says that Filmi Alif Laila is a combination of memoirs, pen sketches, and autobiography, it might be the perfect description of the book.

What makes this book so important to any fan of the Pakistan film industry is its ability to connect with the readers. You can be someone who lived in the era that the book explores or someone who was born after these columns were originally published, but the way the writer has described the workings of the film industry, it remains evergreen. The reasons are both the writer’s narrating style as well as the film industry’s inability to expand, and if you take out the effect of social media from the current era, then there isn’t much difference between the first 15 years of Pakistan’s film industry and that of today, except that it had more learned people at the time.

From penning his thoughts on the experience of conducting the first-ever celebrity interview in Pakistan to describing the thoughts of his fellow journalists from that era, Afaqi talks about everything that happened around him. Be it meeting Noor Jehan and Shaukat Hussain Rizvi after a controversial interview of an actress whom Madam despised was published, to detailing the environment of Muslim Town in Lahore where most of the film personalities resided at the time, the writer minces no words in calling a spade, a spade.

Since Afaqi was stationed most of his life in Lahore, he gives insights about everything that took place during the early days of ‘Lollywood’, the name that became synonymous with the Pakistan film industry. How Aslam Pervez entered the film industry and became an overnight star, why Santosh Kumar was the preferred choice of all the filmmakers of the era, what made Sudhir stand out amongst his contemporaries, and how the local media reacted when Hollywood film Bhowani Junction was shot in the country; answers to these questions can be found in the eight chapters in this book.

Interestingly, according to the writer, he was the only journalist who had access to George Cukor, the director of the Hollywood flick, and the way he describes his first chance meeting with Ava Gardner is nothing short of a fantasy tale. In a country where not much has been written of the film industry, or where not much is known about the history of the film industry, Afaqi’s words are worth millions, because he was usually there when the ‘action’ took place, and lived a life long enough to pen down his memories in his usual style.

Like the fictional character Jessica Fletcher from the famous TV show Murder She Wrote, Afaqi was always where the action was, and that gave him the ideal opportunity to observe some of the very famous people from his era. He talks at length about Master Inayat Hussain, who would take his sweet time to compose songs, describes lyricist Tanveer Naqvi’s habit of taking a shower and wearing his usual ‘work’ clothes before settling down for a session with his composers, explains why Santosh Kumar used to refer to everyone as Maulana and how Darpan and Nayyar Sultana got married, despite the former’s habit of flirting with nearly every other heroine in the film industry. Interesting, isn’t it?

However, he doesn’t go into the details of the scandal that dented Madam Noor Jehan’s first marriage, and cost test cricketer Nazar Mohammad his career, neither does he speak about the film Bedaari that was later banned for being a copy of an Indian patriotic film. What he does talk about is the film’s leading man Ratan Kumar and how he was unable to become successful despite having family support and how his affair with fellow artist Neelo came to an abrupt conclusion. He even gives hints of Shahid and Babra Sharif’s romance and claims that he had no clue whether they were married or not.

Only Afaqi can write detail about actors and actresses who had successful careers in United India, yet migrated to Pakistan for greener pastures. The way he describes actor/director Nazar, his wife Swarn Lata, the initial career of Sabiha Khanum, as well as her brother-in-law Darpan’s short trip to Bollywood, is intriguing to read because not much is known about these real-life stories. His biggest advantage was being in the most progressive era where the film industry became something from nothing, so it wouldn’t be wrong to call him the Forrest Gump of the Pakistan film industry because that’s what he was ― someone who witnessed it all and went onto tell others about it.

If you didn’t know that Nayyar Sultana’s mother didn’t attend her wedding ceremony because she wasn’t convinced that Darpan was husband material, and that the actress had to move into Sabiha Khanum’s house before the wedding or that Saadat Hasan Manto was the person who convinced Afaqi to go ahead and try his hand at writing scripts, you need to get your hands on this book. Because it tells you why Manto was considered a genius and what were the reasons for his decline before his demise. The author even talks about people who helped Manto during his final days and those who didn’t, which is both heartwarming and heartbreaking.

However, as a film critic myself, I have some issues with the writing style that seems repetitive in most places. According to Afaqi, every heroine he met was “beautiful, and made for films” and most of them had a good family background, which differs from what other people from the same era have to say. He describes every film actress as someone from some fairyland and if that heroine became slightly successful, the author would go on to say that she was every filmmaker’s number one choice and that she succeeded because she had all the right ingredients to become famous which seems hard to believe.

It is his word against many others who have either penned sketches of these ‘number one actresses’ or spoken about them on TV and print. In fact, some of the actresses he claims to have been ideal for films have faded into oblivion, and can only be found in this book. Just think for a second, if everyone was so talented in that era, why didn’t the films of these actresses do well, and why did many of them quit the industry after either marrying someone influential or by distancing themselves from the limelight? His bias is clearly visible when it comes to the fair sex, which somehow makes the reader wonder about his credibility.

But as a fellow film journalist who dabbled in filmmaking, for me, our connection was more spiritual. When I read about Afaqi’s inability to drive a car and how his life revolved around the ‘how do I get back home’ syndrome, I instantly connected with him since I usually have the same problem. We might seem more in the Sheldon Cooper club, but some people think of driving as a waste of time, and the author and I are clearly in the same boat. Similarly, when he writes about his friends who wanted him to get settled (considering he moved around with beautiful girls all the time!), or the issues he faced when he wrote his first screenplay, our connection got even stronger.

A dozen years back, some publishers tried to compile Filmi Alif Laila in its entirety and even published some parts of it in three volumes, but that was more on the lines of ‘Best of Filmi Alif Laila’. It did impress the readers but seemed incomplete, just like One Thousand and One Nights would, had the publishers omitted some of the stories. That’s why the newer edition of Filmi Alif Laila features the first eight complete columns that tell a lot about the workings of the film industry in the past. Here, one must commend the efforts of both Atlantis Publications and those at the helm at Zinda Kitabein, who are compiling the Filmi Alif Laila Series in book form and are confident of publishing up to 30 volumes consecutively in the near future.

As this book and the upcoming series are in Urdu, it caters to people well versed in the language, when in fact it should be translated into English and made available to all those who want to know about the Pakistani film industry. Right now, the only book in the English language that talks about our film industry is Mushtaq Gazdar’s Pakistani Cinema 1947-1997 and it only talks about the first 50 years. Hopefully, when more Filmi Alif Laila books are available in the market, the publishers would think of translating them into other languages so those who aren’t familiar with Urdu would be able to realise what made our industry great, back in the day.

The reviewer writes about film, television, and popular culture